Nickel–cadmium battery

From top to bottom – "Gumstick", AA, and AAA Ni–Cd batteries. |

|

| specific energy | 40–60 W·h/kg |

|---|---|

| energy density | 50–150 W·h/L |

| specific power | 150 W/kg |

| Charge/discharge efficiency | 70–90%[1] |

| Self-discharge rate | 10%/month |

| Cycle durability | 2,000 cycles |

| Nominal cell voltage | 1.2 V |

The nickel–cadmium battery (Ni–Cd battery) (commonly abbreviated NiCd or NiCad) is a type of rechargeable battery using nickel oxide hydroxide and metallic cadmium as electrodes.

The abbreviation NiCad is a registered trademark of SAFT Corporation, although this brand name is commonly used to describe all Ni–Cd batteries. The abbreviation NiCd is derived from the chemical symbols of nickel (Ni) and cadmium (Cd).

There are two types of Ni–Cd batteries: sealed and vented. This article mainly deals with sealed cells.

Contents |

Applications

Sealed Ni–Cd cells may be used individually, or assembled into battery packs containing two or more cells. Small cells are used for portable electronics and toys, often using cells manufactured in the same sizes as primary cells. When Ni–Cd batteries are substituted for primary cells, the lower terminal voltage and smaller ampere-hour capacity may reduce performance as compared to primary cells. Miniature button cells are sometimes used in photographic equipment, hand-held lamps (flashlight or torch), computer-memory standby, toys, and novelties.

Specialty Ni–Cd batteries are used in cordless and wireless telephones, emergency lighting, and other applications. With a relatively low internal resistance, they can supply high surge currents. This makes them a favourable choice for remote-controlled electric model airplanes, boats, and cars, as well as cordless power tools and camera flash units. Larger flooded cells are used for aircraft starting batteries, electric vehicles, and standby power.

Voltage

Ni–Cd cells have a nominal cell potential of 1.2 volts (V). This is lower than the 1.5 V of alkaline and zinc–carbon primary cells, and consequently they are not appropriate as a replacement in all applications. However, the 1.5 V of a primary alkaline cell refers to its initial, rather than average, voltage. Unlike alkaline and zinc–carbon primary cells, a Ni–Cd cell's terminal voltage only changes a little as it discharges. Because many electronic devices are designed to work with primary cells that may discharge to as low as 0.90 to 1.0 V per cell, the relatively steady 1.2 V of a Ni–Cd cell is enough to allow operation. Some would consider the near-constant voltage a drawback as it makes it difficult to detect when the battery charge is low.

Ni–Cd batteries used to replace 9 V batteries usually only have six cells, for a terminal voltage of 7.2 volts. While most pocket radios will operate satisfactorily at this voltage, some manufacturers such as Varta made 8.4 volt batteries with seven cells for more critical applications.

12 V Ni–Cd batteries are made up of 10 cells connected in series.

History

The first Ni–Cd battery was created by Waldemar Jungner of Sweden in 1899. At that time, the only direct competitor was the lead–acid battery, which was less physically and chemically robust. With minor improvements to the first prototypes, energy density rapidly increased to about half of that of primary batteries, and significantly greater than lead–acid batteries. Jungner experimented with substituting iron for the cadmium in varying quantities, but found the iron formulations to be wanting. Jungner's work was largely unknown in the United States. Thomas Edison adapted the battery design where he introduced the nickel–iron battery to the US two years after Jungner had built one. In 1906, Jungner established a factory close to Oskarshamn, Sweden to produce flooded design Ni–Cd batteries.

Production in the United States

The first production in the United States began in 1946. Up to this point, the batteries were "pocket type," constructed of nickel-plated steel pockets containing nickel and cadmium active materials. Around the middle of the twentieth century, sintered-plate Ni–Cd batteries became increasingly popular. Fusing nickel powder at a temperature well below its melting point using high pressures creates sintered plates. The plates thus formed are highly porous, about 80 percent by volume. Positive and negative plates are produced by soaking the nickel plates in nickel- and cadmium-active materials, respectively. Sintered plates are usually much thinner than the pocket type, resulting in greater surface area per volume and higher currents. In general, the greater amount of reactive material surface area in a battery, the lower its internal resistance.

Recent developments

In the past few decades, Ni–Cd batteries have had internal resistance as low as alkaline batteries. Today, all consumer Ni–Cd batteries use the "swiss roll" or "jelly-roll" configuration. This design incorporates several layers of positive and negative material rolled into a cylindrical shape. This design reduces internal resistance as there is a greater amount of electrode in contact with the active material in each cell.

Popularity

Advances in battery-manufacturing technologies throughout the second half of the twentieth century have made batteries increasingly cheaper to produce. Battery-powered devices in general have increased in popularity. As of 2000, about 1.5 billion Ni–Cd batteries were produced annually.[2] Up until the mid 1990s, Ni–Cd batteries had an overwhelming majority of the market share for rechargeable batteries in consumer electronics.

Ni–Cd batteries account for 8% of all portable secondary (rechargeable) battery sales in the EU, and in the UK for 9.2% and in Switzerland for 1.3% of all portable battery sales. [3] [4] [5]

Battery characteristics

Comparison with other batteries

Recently, nickel–metal hydride and lithium-ion batteries have become commercially available and cheaper, the former type now rivaling Ni–Cd batteries in cost. Where energy density is important, Ni–Cd batteries are now at a disadvantage compared with nickel–metal hydride and lithium-ion batteries. However, the Ni–Cd battery is still very useful in applications requiring very high discharge rates because it can endure such discharge with no damage or loss of capacity.

Advantages

When compared to other forms of rechargeable battery, the Ni–Cd battery has a number of distinct advantages:

- The batteries are more difficult to damage than other batteries, tolerating deep discharge for long periods. In fact, Ni–Cd batteries in long-term storage are typically stored fully discharged. This is in contrast, for example, to lithium ion batteries, which are less stable and will be permanently damaged if discharged below a minimum voltage.

- Ni–Cd batteries typically last longer, in terms of number of charge/discharge cycles, than other rechargeable batteries such as lead/acid batteries.

- Compared to lead–acid batteries, Ni–Cd batteries have a much higher energy density. A Ni–Cd battery is smaller and lighter than a comparable lead–acid battery. In cases where size and weight are important considerations (for example, aircraft), Ni–Cd batteries are preferred over the cheaper lead–acid batteries.

- In consumer applications, Ni–Cd batteries compete directly with alkaline batteries. A Ni–Cd cell has a lower capacity than that of an equivalent alkaline cell, and costs more. However, since the alkaline battery's chemical reaction is not reversible, a reusable Ni–Cd battery has a significantly longer total lifetime. There have been attempts to create rechargeable alkaline batteries, or specialized battery chargers for charging single-use alkaline batteries, but none that has seen wide usage.

- The terminal voltage of a Ni–Cd battery declines more slowly as it is discharged, compared with carbon–zinc batteries. Since an alkaline battery's voltage drops significantly as the charge drops, most consumer applications are well equipped to deal with the slightly lower Ni–Cd cell voltage with no noticeable loss of performance.

- The capacity of a Ni–Cd battery is not significantly affected by very high discharge currents. Even with discharge rates as high as 50C, a Ni–Cd battery will provide very nearly its rated capacity. By contrast, a lead acid battery will only provide approximately half its rated capacity when discharged at a relatively modest 1.5C.

- Nickel–metal hydride (NiMH) batteries are the newest, and most similar, competitor to Ni–Cd batteries. Compared to Ni–Cd batteries, NiMH batteries have a higher capacity and are less toxic, and are now more cost effective. However, a Ni–Cd battery has a lower self-discharge rate (for example, 20% per month for a Ni–Cd battery, versus 30% per month for a traditional NiMH under identical conditions), although low self-discharge NiMH batteries are now available, which have substantially lower self-discharge than either Ni–Cd or traditional NiMH batteries. This results in a preference for Ni–Cd over NiMH batteries in applications where the current draw on the battery is lower than the battery's own self-discharge rate (for example, television remote controls). In both types of cell, the self-discharge rate is highest for a full charge state and drops off somewhat for lower charge states. Finally, a similarly sized Ni–Cd battery has a slightly lower internal resistance, and thus can achieve a higher maximum discharge rate (which can be important for applications such as power tools).

Disadvantages

- The primary trade-off with Ni–Cd batteries is their higher cost and the use of cadmium. This heavy metal is an environmental hazard, and is highly toxic to all higher forms of life. They are also more costly than lead–acid batteries because nickel and cadmium cost more.

- One biggest disadvantages is that the battery exhibits a very marked negative temperature coefficient. This means that as the cell temperature rises, the internal resistance falls. This can pose considerable charging problems, particularly with the relatively simple charging systems employed for lead–acid type batteries. Whilst lead–acid batteries can be charged by simply connecting a dynamo to them, with a simple electromagnetic cut-out system for when the dynamo is stationary or an over-current occurs, the Ni–Cd battery under a similar charging scheme would exhibit thermal runaway, where the charging current would continue to rise until the over-current cut-out operated or the battery destroyed itself. This is the principal factor that prevents its use as engine-starting batteries. Today with alternator-based charging systems with solid-state regulators, the construction of a suitable charging system would be relatively simple, but the car manufacturers are reluctant to abandon tried-and-tested technology.

Availability

Ni–Cd cells are available in the same sizes as alkaline batteries, from AAA through D, as well as several multi-cell sizes, including the equivalent of a 9 volt battery. A fully charged single Ni–Cd cell, under no load, carries a potential difference of between 1.25 and 1.35 volts, which stays relatively constant as the battery is discharged. Since an alkaline battery near fully discharged may see its voltage drop to as low as 0.9 volts, Ni–Cd cells and alkaline cells are typically interchangeable for most applications.

In addition to single cells, batteries exist that contain up to 300 cells (nominally 360 volts, actual voltage under no load between 380 and 420 volts). This many cells are mostly used in automotive and heavy-duty industrial applications. For portable applications, the number of cells is normally below 18 cells (24V). Industrial-sized flooded batteries are available with capacities ranging from 12.5Ah up to several hundred Ah.

Characteristics

The maximum discharge rate for a Ni–Cd battery varies by size. For a common AA-size cell, the maximum discharge rate is approximately 18 amps; for a D size battery the discharge rate can be as high as 35 amps.

Model-aircraft or -boat builders often take much larger currents of up to a hundred amps or so from specially constructed Ni–Cd batteries, which are used to drive main motors. 5–6 minutes of model operation is easily achievable from quite small batteries, so a reasonably high power-to-weight figure is achieved, comparable to internal combustion motors, though of lesser duration. In this, however, they have been largely superseded by lithium polymer (Lipo) and lithium iron phosphate (LiFe) batteries, which can provide even higher energy densities.

Charging

Ni–Cd batteries can be charged at several different rates, depending on how the cell was manufactured. The charge rate is measured based on the percentage of the amp-hour capacity the battery is fed as a steady current over the duration of the charge. Regardless of the charge speed, more energy must be supplied to the battery than its actual capacity, to account for energy loss during charging, with faster charges being more efficient. For example, an "overnight" charge, might consist of supplying a current equals to one tenth the amperehour rating ( C/10 ) for 14–16 hours; that is, a 100 mAh battery takes 10mA for 14 hours, for a total of 140 mAh to charge at this rate. At the rapid-charge rate, done at 100% of the rated capacity of the battery in 1 hour (1C), the battery holds roughly 80% of the charge, so a 100 mAh battery takes 120 mAh to charge (that is, approximately 1 hour and fifteen minutes). Some specialized batteries can be charged in as little as 10–15 minutes at a 4C or 6C charge rate, but this is very uncommon. It also exponentially increases the risk of the cells overheating and venting due to an internal overpressure condition: the cell's rate of temperature rise is governed by its internal resistance and the square of the charging rate. At a 4C rate, the amount of heat generated in the cell is sixteen times higher than the heat at the 1C rate. The downside to faster charging is the higher risk of overcharging, which can damage the battery.[6] and the increased temperatures the cell has to endure (which potentially shortens its life).

The safe temperature range when in use is between −20°C and 45°C. During charging, the battery temperature typically stays low, around 0°C (the charging reaction absorbs heat), but as the battery nears full charge the temperature will rise to 45–50°C. Some battery chargers detect this temperature increase to cut off charging and prevent over-charging.

When not under load or charge, a Ni–Cd battery will self-discharge approximately 10% per month at 20°C, ranging up to 20% per month at higher temperatures. It is possible to perform a trickle charge at current levels just high enough to offset this discharge rate; to keep a battery fully charged. However, if the battery is going to be stored unused for a long period of time, it should be discharged down to at most 40% of capacity (some manufacturers recommend fully discharging and even short-circuiting once fully discharged), and stored in a cool, dry environment.

Charge condition

High quality Ni–Cd batteries have a thermal cut-off so if the battery gets too hot the charger stops. If a battery is still warm from discharging and been put on charge, it will not get the full charge possible. In that case, let the battery cool to room temperature, then charge. Watch for the correct polarity. Leave charger in a cool place when charging to get best results.

Charging method

A Ni–Cd battery requires a charger with a slightly different voltage than for a lead–acid battery, especially if the battery has 11 or 12 cells. Also a charge termination method is needed if a fast charger is used. Often battery packs have a thermal cut-off inside that feeds back to the charger telling it to stop the charging once the battery has heated up and/or a voltage peaking sensing circuit. At room temperature during normal charge conditions the cell voltage increases from an initial 1.2 V to an end-point of about 1.45 V. The rate of rise increases markedly as the cell approaches full charge. The end-point voltage decreases slightly with increasing temperature.

Electrochemistry

A fully charged Ni–Cd cell contains:

- a nickel(III) oxide-hydroxide positive electrode plate.

- a cadmium negative electrode plate.

- a separator.

- and an alkaline electrolyte (potassium hydroxide).

Ni–Cd batteries usually have a metal case with a sealing plate equipped with a self-sealing safety valve. The positive and negative electrode plates, isolated from each other by the separator, are rolled in a spiral shape inside the case. This is known as the jelly-roll design and allows a Ni–Cd cell to deliver a much higher maximum current than an equivalent size alkaline cell. Alkaline cells have a bobbin construction where the cell casing is filled with electrolyte and contains a graphite rod which acts as the positive electrode. As a relatively small area of the electrode is in contact with the electrolyte (as opposed to the jelly-roll design), the internal resistance for an equivalent sized alkaline cell is higher which limits the maximum current that can be delivered.

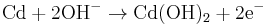

The chemical reactions during discharge are:

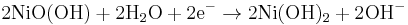

at the cadmium electrode, and

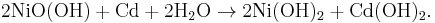

at the nickel electrode. The net reaction during discharge is

During recharge, the reactions go from right to left. The alkaline electrolyte (commonly KOH) is not consumed in this reaction and therefore its Specific Gravity, unlike in lead–acid batteries, is not a guide to its state of charge.

When Jungner built the first Ni–Cd batteries, he used nickel oxide in the positive electrode, and iron and cadmium materials in the negative. It was not until later that pure cadmium metal and nickel hydroxide were used. Until about 1960, the chemical reaction was not completely understood. There were several speculations as to the reaction products. The debate was finally resolved by spectrometry, which revealed cadmium hydroxide and nickel hydroxide.

Another historically important variation on the basic Ni–Cd cell is the addition of lithium hydroxide to the potassium hydroxide electrolyte. This was believed to prolong the service life by making the cell more resistant to electrical abuse. The Ni–Cd battery in its modern form is extremely resistant to electrical abuse anyway, so this practice has been discontinued.

Problems

Overcharging

Overcharging must be considered in the design of most rechargeable batteries. In the case of Ni–Cd batteries, there are two possible results of overcharging:

- If the negative electrode is overcharged, hydrogen gas is produced.

- If the positive electrode is overcharged, oxygen gas is produced.

For this reason, the negative electrode is always designed for a higher capacity than the positive, to avoid releasing hydrogen gas. There is still the problem of eliminating oxygen gas, to avoid rupture of the cell casing. Ni–Cd cells are vented, with seals that fail at high internal gas pressures. The sealing mechanism must allow gas to escape from inside the cell, and seal again properly when the gas is expelled. This complex mechanism, unnecessary in alkaline batteries, contributes to their higher cost.

Ni–Cd cells dealt with in this article are of the sealed type (see also vented type). Cells of this type consist of a pressure vessel that is supposed to contain any generation of oxygen and hydrogen gasses until they can recombine back to water. Such generation typically occurs during rapid charge and discharge and exceedingly at overcharge condition. If the pressure exceeds the limit of the safety valve, water in the form of gas is lost. Since the vessel is designed to contain an exact amount of electrolyte this loss will rapidly affect the capacity of the cell and its ability to receive and deliver current. To detect all conditions of overcharge demands great sophistication from the charging circuit and a cheap charger will eventually damage even the best quality cells.[7]

Cell reversal

Another potential problem is reverse charging. This can occur due to an error by the user, or more commonly, when a battery of several cells is fully discharged. Because there is a slight variation in the capacity of cells in a battery, one of the cells will usually be fully discharged before the others, at which point reverse charging begins seriously damaging that cell, reducing battery life. The by-product of reverse charging is hydrogen gas, which can be dangerous. Some commentators advise that one should never discharge multi-cell Ni–Cd batteries to zero voltage; for example, incandescent lights should be turned off when they are yellow; before they go out completely.

A common form of this deprecation occurs when cells connected in series develop unequal voltages and discharge near zero voltage. The first cell that reaches zero is pushed beyond to negative voltage and gases generated open the seal and dry the cell.

In modern cells, an excess of anti-polar material (basically active material ballast at positive electrode) is inserted to allow for moderate negative charge without damage to the cell. This excess material slows down the start of oxygen generation at the negative plate. This means a cell can survive a negative voltage of about −0.2 to −0.4 volts. However if discharge is continued even further, this excess ballast is used up and both electrodes change polarity, causing destructive gassing (gas generation).

Battery packs with multiple cells in series should be operated well above 1 volt per cell to avoid placing the lowest capacity cell in danger of going negative. Battery packs that can be disassembled into cells should be periodically zeroed and charged individually to equalize the voltages. However, this does not help if old and new cells are mixed, since their different capacities will result in different discharge times and voltages.[7]

Memory and lazy battery effects

Ni–Cd batteries may suffer from a "memory effect" if they are discharged and recharged to the same state of charge hundreds of times. The apparent symptom is that the battery "remembers" the point in its charge cycle where recharging began and during subsequent use suffers a sudden drop in voltage at that point, as if the battery had been discharged. The capacity of the battery is not actually reduced substantially. Some electronics designed to be powered by Ni–Cd batteries are able to withstand this reduced voltage long enough for the voltage to return to normal. However, if the device is unable to operate through this period of decreased voltage, it will be unable to get enough energy out of the battery, and for all practical purposes, the battery appears "dead" earlier than normal.

There is much evidence that the memory effect story originated from orbiting satellites, where they were typically charging for twelve hours out of twenty-four for several years.[8] After this time, it was found that the capacities of the batteries had declined significantly, but were still perfectly fit for use. It is unlikely that this precise repetitive charging (e.g., 1000 charges / discharges with less than 2% variability) could ever be reproduced by consumers using electrical goods.

An effect with similar symptoms to the memory effect is the so-called voltage depression or lazy battery effect. This results from repeated overcharging; the symptom is that the battery appears to be fully charged but discharges quickly after only a brief period of operation. In rare cases, much of the lost capacity can be recovered by a few deep-discharge cycles, a function often provided by automatic battery chargers. However, this process may reduce the shelf life of the battery.[9] If treated well, a Ni–Cd battery can last for 1000 cycles or more before its capacity drops below half its original capacity.

Dendritic shorting

When not used regularly, dendrites tend to develop. Dendrites are thin, conductive crystals that may penetrate the separator membrane between electrodes. This leads to internal short circuits and premature failure, long before the 800–1000 charge/discharge cycle life claimed by most vendors. Sometimes, applying a brief, high-current charging pulse to individual cells can clear these dendrites, but they will typically reform within a few days or even hours. Cells in this state have reached the end of their useful life and should be replaced. Many battery guides, circulating on the Internet and online auctions, promise to restore dead cells using the above principle, but achieve very short-term results at best.

Environmental consequences of cadmium

Ni–Cd batteries contain between 6% (for industrial batteries) and 18% (for consumer batteries) cadmium, which is a toxic heavy metal and therefore requires special care during battery disposal. In the United States, part of the battery price is a fee for its proper disposal at the end of its service lifetime. Under the so-called "batteries directive" (2006/66/EC), the sale of consumer Ni–Cd batteries has now been banned within the European Union except for medical use; alarm systems; emergency lighting; and portable power tools. This last category is to be reviewed after 4 years. Under the same EU directive, used industrial Ni–Cd batteries must be collected by their producers in order to be recycled in dedicated facilities.

Cadmium, being a heavy metal, can cause substantial pollution when landfilled or incinerated. Because of this, many countries now operate recycling programs to capture and reprocess old batteries.

Safety

Manufacturers typically supply instructions for safe handling, use, and disposal. These warn against physical damage, short-circuiting when fully charged, and overcharging.[10]

See also

- Nickel–cadmium battery vented cell type

- Nickel–iron battery

- Battery recycling

- Battery holder

- Nickel metal hydride battery

- Power-to-weight ratio

References

- ^ Charging nickel-based batteries

- ^ "Solucorp Unveils Pollution Preventing, Self-Remediating Ni-Cd Battery to International Markets". Business Wire. 2006-10-19. http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0EIN/is_2006_Oct_19/ai_n27033828. Retrieved 2008-08-01.

- ^ [1] Battery Waste Management – 2006 DEFRA

- ^ [2] INOBAT 2008 statistics.

- ^ [3] EPBA statistics – 2000

- ^ NiCad Battery Charging Basics

- ^ a b GP Nickel Cadmium Technical Handbook (Dead or broken link)

- ^ Goodman, Marty (1997-10-13). "Lead-Acid or NiCd Batteries?". Articles about Bicycle Commuting and Lighting. Harris Cyclery. http://www.sheldonbrown.com/marty_sla-nicad.html. Retrieved 2009-02-18.

- ^ Dan's Quick Guide to Memory Effect

- ^ For example, Rayovac Safety Data Sheet Rayovac Safety Data Sheet

- Bergstrom, Sven. "Nickel–Cadmium Batteries – Pocket Type". Journal of the Electrochemical Society, September 1952. 1952 The Electrochemical Society.

- Ellis, G. B., Mandel, H., and Linden, D. "Sintered Plate Nickel–Cadmium Batteries". Journal of the Electrochemical Society, September 1952. 1952 The Electrochemical Society.