Nakayama lemma

In mathematics, more specifically modern algebra and commutative algebra, Nakayama's lemma also known as the Krull–Azumaya theorem[1] governs the interaction between the Jacobson radical of a ring (typically a commutative ring) and its finitely generated modules. Informally, the lemma immediately gives a precise sense in which finitely generated modules over a commutative ring behave like vector spaces over a field. It is a significant tool in algebraic geometry, because it allows local data on algebraic varieties, in the form of modules over local rings, to be studied pointwise as vector spaces over the residue field of the ring.

The lemma is named after the Japanese mathematician Tadashi Nakayama and introduced in its present form in Nakayama (1951), although it was first discovered in the special case of ideals in a commutative ring by Wolfgang Krull and then in general by Goro Azumaya (1951).[2] In the commutative case, the lemma is a simple consequence of a generalized form of the Cayley–Hamilton theorem, an observation made by Michael Atiyah (1969). The special case of the noncommutative version of the lemma for right ideals appears in Nathan Jacobson (1945), and so the noncommutative Nakayama lemma is sometimes known as the Jacobson–Azumaya theorem.[1] The latter has various applications in the theory of Jacobson radicals.[3]

Contents |

Statement

Let R be a commutative ring with identity 1. The following is Nakayama's lemma, as stated in Matsumura (1989):

Statement 1: Let I be an ideal in R, and M a finitely-generated module over R. If IM = M, then there exists an r ∈ R with r ≡ 1 (mod I), such that rM = 0.

This is proven below.

The following corollary is also known as Nakayama's lemma, and it is in this form that it most often appears.[4]

Statement 2: With conditions as above, if I is contained in the Jacobson radical of R, then necessarily M = 0.

- Proof: r−1 (with r as above) is in the Jacobson radical so r is invertible.

More generally, one has

Statement 3: If M = N + IM for some ideal I in the Jacobson radical of R and M is finitely-generated, then M = N.

- Proof: Apply Statement 2 to M/N.

The following result manifests Nakayama's lemma in terms of generators[5]

Statement 4: Let I be an ideal in the Jacobson radical of R, and suppose that M is finitely-generated. If m1,...,mn have images in M/IM that generate it as an R-module, then m1,...,mn also generate M as an R-module.

- Proof: Apply Statement 2 to N = M/ΣiRmi.

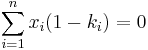

This conclusion of the last corollary holds without assuming in advance that M is finitely generated, provided that M is assumed to be a complete and separated module with respect to the I-adic topology.[6] Here separatedness means that the I-adic topology satisfies the T1 separation axiom, and is equivalent to

Consequences

Local rings

In the special case of a finitely generated module M over a local ring R with maximal ideal m, the quotient M/mM is a vector space over the field R/m. Statement 4 then implies that a basis of M/mM lifts to a minimal set of generators of M. Conversely, every minimal set of generators of M is obtained in this way, and any two such sets of generators are related by an invertible matrix with entries in the ring.

In this form, Nakayama's lemma takes on concrete geometrical significance. Local rings arise in geometry as the germs of functions at a point. Finitely generated modules over local rings arise quite often as germs of sections of vector bundles. Working at the level of germs rather than points, the notion of finite dimensional vector bundle gives way to that of a coherent sheaf. Informally, Nakayama's lemma says that one can still regard a coherent sheaf as coming from a vector bundle in some sense. More precisely, let F be a coherent sheaf of OX-modules over an arbitrary scheme X. The stalk of F at a point p ∈ X, denoted by Fp, is a module over the local ring Op. The fibre of F at p is the vector space F(p) = Fp/mpFp where mp is the maximal ideal of Op. Nakayama's lemma implies that a basis of the fibre F(p) lifts to a minimal set of generators of Fp. That is:

- Any basis of the fiber of a coherent sheaf F at a point comes from a minimal basis of local sections.

Going up and going down

The going up theorem is essentially a corollary of Nakayama's lemma.[7] It asserts:

- Let R ⊂ S be an integral extension of commutative rings, and P a prime ideal of R. Then there is a prime ideal Q in S such that Q ∩ R = P. Moreover, Q can be chosen to contain any prime Q1 of S such that Q1 ∩ R ⊂ P.

To give geometrical context for this result, integral extensions correspond to proper maps of algebraic varieties. For varieties over the complex field, proper simply means that the inverse image of a compact set in the usual topology is again compact. Going up then implies that the image of an algebraic subvariety under a proper map is again an algebraic subvariety.[8]

Module epimorphisms

Nakayama's lemma makes precise one sense in which finitely generated modules over a commutative ring are like vector spaces over a field. The following consequence of Nakayama's lemma gives another way in which this is true:

- If M is a finitely generated R-module and ƒ : M → M is a surjective endomorphism, then ƒ is an isomorphism.[9]

Over a local ring, one can say more about module epimorphisms:[10]

- Suppose that R is a local ring with maximal ideal m, and M, N are finitely generated R-modules. If φ : M → N is an R-linear map such that the quotient φm : M/mM → N/mN is surjective, then φ is surjective.

Homological versions

Nakayama's lemma also has several versions in homological algebra. The above statement about epimorphisms can be used to show:[10]

- Let M be a finitely generated module over a local ring. Then M is projective if and only if it is free.

A geometrical and global counterpart to this is the Serre–Swan theorem, relating projective modules and coherent sheaves.

More generally, one has[11]

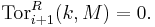

- Let R be a local ring and M a finitely generated module over R. Then the projective dimension of M over R is equal to the length of every minimal free resolution of M. Moreover, the projective dimension is equal to the global dimension of M, which is by definition the smallest integer i ≥ 0 such that

-

- Here k is the residue field of R and Tor is the tor functor.

Proof

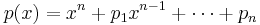

A standard proof of the Nakayama lemma uses the following technique due to Atiyah & Macdonald (1969).[12]

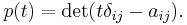

- Let M be an R-module generated by n elements, and φ : M → M an R-linear map. If there is an ideal I of R such that φ(M) ⊂ IM, then there is a monic polynomial

-

- with pk ∈ Ik, such that

- as an endomorphism of M.

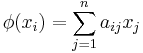

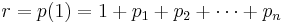

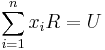

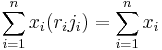

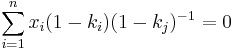

This assertion is precisely a generalized version of the Cayley–Hamilton theorem, and the proof proceeds along the same lines. On the generators xi of M, one has a relation of the form

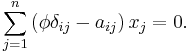

where aij ∈ I. Thus

The required result follows by multiplying by the adjugate of the matrix (φδij − aij) and invoking Cramer's rule. One finds then det(φδij − aij) = 0, so the required polynomial is

To prove Nakayama's lemma from the Cayley–Hamilton theorem, assume that IM = M and take φ to be the identity on M. Then define a polynomial p(x) as above. Then

has the required property.

Noncommutative case

A version of the lemma holds for right modules over non-commutative unitary rings R. The resulting theorem is sometimes known as the Jacobson–Azumaya theorem.[13]

Let J(R) be the Jacobson radical of R. If U is a right module over a ring, R, and I is an right ideal in R, then define U·I to be the set of all (finite) sums of elements of the form u·i, where · is simply the action of R on U. Necessarily, U·I is a submodule of U.

If V is a maximal submodule of U, then U/V is simple. So U·J(R) is necessarily a subset of V, by the definition of J(R) and the fact that U/V is simple.[14] Thus, if U contains at least one (proper) maximal submodule, U·J(R) is a proper submodule of U. However, this need not hold for arbitrary modules U over R, for U need not contain any maximal submodules.[15] Naturally, if U is a Noetherian module, this holds. If R is Noetherian, and U is finitely generated, then U is a Noetherian module over R, and the conclusion is satisfied.[16] Somewhat remarkable is that the weaker assumption, namely that U is finitely generated as an R-module (and no finiteness assumption on R), is sufficient to guarantee the conclusion. This is essentially the statement of Nakayama's lemma.[17]

Precisely, one has:

- Nakayama's lemma: Let U be a finitely generated right module over a ring R. If U is a non-zero module, then U·J(R) is a proper submodule of U.[17]

Proof

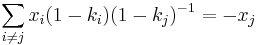

Let X be a finite subset of U, minimal with respect to the property that it generates U. Since U is non-zero, this set X is nonempty. Denote every element of X by xi, for  . Since X generates U,

. Since X generates U,

Suppose,  , to obtain a contradiction. Since,

, to obtain a contradiction. Since,  , we conclude,

, we conclude,

, for

, for  , and

, and

By associativity,

Since J(R) is a (two-sided) ideal in R, we have  for every i, and thus this becomes

for every i, and thus this becomes

, for

, for

Applying distributivity,

Since  , it is quasiregular and thus,

, it is quasiregular and thus,  , for all i, where U(R) denotes the group of units in R. Choose some j and write,

, for all i, where U(R) denotes the group of units in R. Choose some j and write,

Therefore,

Thus xj is a linear combination of the elements of X distinct from xj. This contradicts the minimality of X and establishes the result.[18]

Graded version

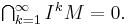

There is also a graded version of Nakayama's lemma. Let R be a graded ring (over the integers), and let  denote the ideal generated by positively graded elements. Then if M is a graded module over R for which

denote the ideal generated by positively graded elements. Then if M is a graded module over R for which  for i sufficiently negative (in particular, if M is finitely generated and R does not contain elements of negative degree) such that

for i sufficiently negative (in particular, if M is finitely generated and R does not contain elements of negative degree) such that  , then

, then  . Of particular importance is the case that R is a polynomial ring with the standard grading, and M is a finitely generated module.

. Of particular importance is the case that R is a polynomial ring with the standard grading, and M is a finitely generated module.

The proof is much easier than in the ungraded case: taking i to be the least integer such that  , we see that

, we see that  does not appear in

does not appear in  , so either

, so either  , or such an i does not exist, i.e.,

, or such an i does not exist, i.e.,  .

.

See also

Notes

- ^ a b Nagata 1962, §A.2

- ^ Nagata 1962, §A.2; Matsumura 1989, p. 8

- ^ Isaacs 1993, Corollary 13.13, p. 184

- ^ Eisenbud 1995, Corollary 4.8; Atiyah & Macdonald (1969, Proposition 2.6)

- ^ Eisenbud 1995, Corollary 4.8(b)

- ^ Eisenbud 1993, Exercise 7.2

- ^ Eisenbud 1993, §4.4

- ^ Over the complex field, this result is also known as the proper mapping theorem; see Griffiths & Harris (1994, p. 34).

- ^ Matsumura 1989, Theorem 2.4

- ^ a b Griffiths & Harris 1994, p. 681

- ^ Eisenbud 1993, Corollary 19.5

- ^ Matsumura 1989, p. 7: "A standard technique applicable to finite A-modules is the 'determinant trick'..." See also the proof contained in Eisenbud (1995, §4.1).

- ^ Nagata 1962, §A2

- ^ Isaacs 1993, p. 182

- ^ Isaacs 1993, p. 183

- ^ Isaacs 1993, Theorem 12.19, p. 172

- ^ a b Isaacs 1993, Theorem 13.11, p. 183

- ^ Isaacs 1993, Theorem 13.11, p. 183; Isaacs 1993, Corollary 13.12, p. 183

References

- Atiyah, Michael F.; Macdonald, Ian G. (1969), Introduction to Commutative Algebra, Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Azumaya, Gorô (1951), "On maximally central algebras", Nagoya Mathematical Journal 2: 119–150, ISSN 0027-7630, MR0040287.

- Eisenbud, David (1995), Commutative algebra, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 150, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-94268-1; 978-0-387-94269-8, MR1322960

- Griffiths, Phillip; Harris, Joseph (1994), Principles of algebraic geometry, Wiley Classics Library, New York: John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 978-0-471-05059-9, MR1288523

- Hartshorne, Robin (1977), Algebraic Geometry, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 52, Springer-Verlag.

- Isaacs, I. Martin (1993), Algebra, a graduate course (1st ed.), Brooks/Cole Publishing Company, ISBN 0-534-19002-2

- Jacobson, Nathan (1945), "The radical and semi-simplicity for arbitrary rings", American Journal of Mathematics 67 (2): 300–320, doi:10.2307/2371731, ISSN 0002-9327, JSTOR 2371731, MR0012271.

- Matsumura, Hideyuki (1989), Commutative ring theory, Cambridge Studies in Advanced Mathematics, 8 (2nd ed.), Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-36764-6, MR1011461.

- Nagata, Masayoshi (1975), Local rings, Robert E. Krieger Publishing Co., Huntington, N.Y., ISBN 978-0-88275-228-0, MR0460307.

- Nakayama, Tadasi (1951), "A remark on finitely generated modules", Nagoya Mathematical Journal 3: 139–140, ISSN 0027-7630, MR0043770.