Municipal bond

A municipal bond is a bond issued by a city or other local government, or their agencies. Potential issuers of municipal bonds includes cities, counties, redevelopment agencies, special-purpose districts, school districts, public utility districts, publicly owned airports and seaports, and any other governmental entity (or group of governments) below the state level. Municipal bonds may be general obligations of the issuer or secured by specified revenues.

In the United States, interest income received by holders of municipal bonds is often exempt from the federal income tax and from the income tax of the state in which they are issued, although municipal bonds issued for certain purposes may not be tax exempt.

Unlike new issue stocks that are brought to market with price restrictions until the deal is sold, municipal bonds are free to trade at any time once they are purchased by the investor. Professional traders regularly trade and retrade the same bonds several times a week.

Contents[hide] |

History

Historically municipal debt predates corporate debt by several centuries: the early Renaissance Italian city-states borrowed money from major banking families. Borrowing by American cities dates to the seventeenth century; records of U.S. municipal bonds indicate use around the early 1800’s. Officially the first recorded municipal bond, a general obligation bond was issued by the City of New York for a canal in 1812. During the 1840’s, many U.S. cities were in debt; roughly by 1843 cities had about 25 million in outstanding debt. In the pursuing decades rapid urban development demonstrated a correspondingly explosive growth in municipal debt. The debt was used to finance both urban improvements and a growing system of free public education systems.

Years after the civil war, significant local debt was issued to build railroads. Railroads were private corporations and these bonds were very similar to today’s industrial revenue bonds. Construction costs in 1873 for one of the largest transcontinental railroads, the northern pacific closed down access to new capital.

The largest bank of the country, which was owned by the same investor as by Northern Pacific, collapsed. Smaller firms followed suit as well as the stock market. The 1873 panic and years of depression that followed put an abrupt but temporary halt to the rapid growth of municipal debt.

Responding to widespread defaults that jolted the municipal bond market of the day, new state statues were passed that restricted the issuance of local debt. Several states wrote these restrictions into their constitutions. Railroad bonds and their legality were widely challenged; this gave rise to the market-wide demand that an opinion of qualified bond counsel accompany each new issue.

The U.S. economy began to move forward once again, municipal debt continued its momentum, this maintained well into the early part of the twentieth century. Regrettably the great depression of the 1930’s halted growth, although defaults were not as severe as in the 1870s. Outstanding municipal debt then fell during World War II. Many American resources were devoted to the military. Prewar municipal debt burst into a new period of rapid growth for an ever-increasing variety of uses. After World War II, state and local debt was $145 per capita. In 1998, according to the U.S. census, state debt was $1,791 per capita. Local per capita debt in 1996, the most current Census data Available, was 2704. Federal debt was $20,374 per capita at the end of 1998.

In addition to the 50 states and their local governments (including cities, counties, villages and school districts), the District of Columbia and U.S. territories and possessions (American samoa, the commonwealth of Puerto Rico, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, and the U.S. virgin Islands) can and do issue municipal bonds. Another important category of municipal bond issuers includes authorities and special districts, which have grown in number and variety in recent years.

The two most prominent early authorities were the Port of New York Authority, formed in 1921 and renamed Port Authority of New York and New Jersey in 1972, and the Triborough Bridge Authority (now the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority), formed in 1933. The debt issues of these two authorities are exempt from federal, state and local governments taxes.[1]

Types of tax-exempt bonds

Municipal bonds provide tax exemption from federal taxes and many state and local taxes, depending on the laws of each state. Municipal securities consist of both short-term issues (often called notes, which typically mature in one year or less) and long-term issues (commonly known as bonds, which mature in more than one year). Short-term notes are used by an issuer to raise money for a variety of reasons: in anticipation of future revenues such as taxes, state or federal aid payments, and future bond issuances; to cover irregular cash flows; meet unanticipated deficits; and raise immediate capital for projects until long-term financing can be arranged. Bonds are usually sold to finance capital projects over the longer term.

The two basic types of municipal bonds are:

- General obligation bonds: Principal and interest are secured by the full faith and credit of the issuer and usually supported by either the issuer’s unlimited or limited taxing power. In many cases, general obligation bonds are voter-approved.

- Revenue bonds: Principal and interest are secured by revenues derived from tolls, charges or rents from the facility built with the proceeds of the bond issue. Public projects financed by revenue bonds include toll roads, bridges, airports, water and sewage treatment facilities, hospitals and subsidized housing. Many of these bonds are issued by special authorities created for that particular purpose.

Most municipal notes and bonds are issued in minimum denominations of $5,000 or multiples of $5,000.

Purpose of municipal bonds

Municipal bonds are securities that are issued for the purpose of financing the infrastructure needs of the issuing municipality. These needs vary greatly but can include schools, streets and highways, bridges, hospitals, public housing, sewer and water systems, power utilities, and various public projects.

Municipal bond issuers

Municipal bonds are issued by states, cities, and counties, (the municipal issuer) to raise funds. The methods and traces of issuing debt are governed by an extensive system of laws and regulations, which vary by state. Bonds bear interest at either a fixed or variable rate of interest, which can be subject to a cap known as the maximum legal limit. If a bond measure is proposed in a local county election, a Tax Rate Statement may be provided to voters, detailing best estimates of the tax rate required to levy and fund the bond.

The issuer of a municipal bond receives a cash payment at the time of issuance in exchange for a promise to repay the investors who provide the cash payment (the bond holder) over time. Repayment periods can be as short as a few months (although this is rare) to 20, 30, or 40 years, or even longer.

The issuer typically uses proceeds from a bond sale to pay for capital projects or for other purposes it cannot or does not desire to pay for immediately with funds on hand. Tax regulations governing municipal bonds generally require all money raised by a bond sale to be spent on one-time capital projects within three to five years of issuance.[2] Certain exceptions permit the issuance of bonds to fund other items, including ongoing operations and maintenance expenses, the purchase of single-family and multi-family mortgages, and the funding of student loans, among many other things.

Because of the special tax-exempt status of most municipal bonds, investors usually accept lower interest payments than on other types of borrowing (assuming comparable risk). This makes the issuance of bonds an attractive source of financing to many municipal entities, as the borrowing rate available in the open market is frequently lower than what is available through other borrowing channels.

Municipal bonds are one of several ways states, cities and counties can issue debt. Other mechanisms include certificates of participation and lease-buyback agreements. While these methods of borrowing differ in legal structure, they are similar to the municipal bonds described in this article.

Municipal bond holders

Municipal bond holders may purchase bonds either directly from the issuer at the time of issuance (on the primary market), or from other bond holders at some time after issuance (on the secondary market). In exchange for an upfront investment of capital, the bond holder receives payments over time composed of interest on the invested principal, and a return of the invested principal itself (see bond).

Repayment schedules differ with the type of bond issued. Municipal bonds typically pay interest semi-annually. Shorter term bonds generally pay interest only until maturity; longer term bonds generally are amortized through annual principal payments. Longer and shorter term bonds are often combined together in a single issue that requires the issuer to make approximately level annual payments of interest and principal. Certain bonds, known as zero coupon or capital appreciation bonds, accrue interest until maturity at which time both interest and principal become due.

Bond measure

A bond measure is an initiative to sell bonds for the purpose of acquiring funds for various public works projects, such as research, transportation infrastructure improvements, and others. These measures are put up for a vote in general elections and must be approved by a plurality or majority of voters, depending on the specific project in question.

Such measures are very often used in the United States when other revenue sources, such as taxes, are limited or non-existent.

Characteristics of municipal bonds

Taxability

One of the primary reasons municipal bonds are considered separately from other types of bonds is their special ability to provide tax-exempt income. Interest paid by the issuer to bond holders is often exempt from all federal taxes, as well as state or local taxes depending on the state in which the issuer is located, subject to certain restrictions. Bonds issued for certain purposes are subject to the alternative minimum tax.

The type of project or projects that are funded by a bond affects the taxability of income received on the bonds held by bond holders. Interest earnings on bonds that fund projects that are constructed for the public good are generally exempt from federal income tax, while interest earnings on bonds issued to fund projects partly or wholly benefiting only private parties, sometimes referred to as private activity bonds, may be subject to federal income tax. However, qualified private activity bonds, whether issued by a governmental unit or private entity, are exempt from federal taxes because the bonds are financing services or facilities that, while meeting the private activity tests, are needed by a government.

The laws governing the taxability of municipal bond income are complex; however, bonds are typically certified by a law firm as either tax-exempt (federal and/or state income tax) or taxable before they are offered to the market. Purchasers of municipal bonds should be aware that not all municipal bonds are tax-exempt.

Risk

The risk ("security") of a municipal bond is a measure of how likely the issuer is to make all payments, on time and in full, as promised in the agreement between the issuer and bond holder (the "bond documents"). Different types of bonds are secured by various types of repayment sources, based on the promises made in the bond documents:

- General obligation bonds promise to repay based on the full faith and credit of the issuer; these bonds are typically considered the most secure type of municipal bond, and therefore carry the lowest interest rate.

- Revenue bonds promise repayment from a specified stream of future income, such as income generated by a water utility from payments by customers.

- Assessment bonds promise repayment based on property tax assessments of properties located within the issuer's boundaries.

In addition, there are several other types of municipal bonds with different promises of security.

The probability of repayment as promised is often determined by an independent reviewer, or "rating agency". The three main rating agencies for municipal bonds in the United States are Standard & Poor's, Moody's, and Fitch. These agencies can be hired by the issuer to assign a bond rating, which is valuable information to potential bond holders that helps sell bonds on the primary market.

Municipal bonds have traditionally had very low rates of default as they are backed either by revenue from public utilities (revenue bonds), or state and local government power to tax (general obligation bonds). However, sharp drops in property valuations resulting from the 2009 mortgage crisis have led to strained state and local finances, potentially leading to municipal defaults. For example, Harrisburg, PA, when faced with falling revenues, skipped several bond payments on a municipal waste to energy incinerator and did not budget more than $68m for obligations related to this public utility. The prospect of Chapter 9 municipal bankruptcy was raised by the Controller of Harrisburg, although it was opposed by Harrisburg's mayor.[3]

Disclosures to investors

Key information about new issues of municipal bonds (including, among other things, the security pledged for repayment of the bonds, the terms of payment of interest and principal of the bonds, the tax-exempt status of the bonds, and material financial and operating information about the issuer of the bonds) typically is found in the issuer's official statement. Official statements generally are available at no charge from the Electronic Municipal Market Access system (EMMA) at http://emma.msrb.org operated by the Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board (MSRB). For most municipal bonds issued in recent years, the issuer is also obligated to provide continuing disclosure to the marketplace, including annual financial information and notices of the occurrence of certain material events (including notices of defaults, rating downgrades, events of taxability, etc.). Continuing disclosures also are available for free from the EMMA continuing disclosure service.

Comparison to corporate bonds

Because municipal bonds are most often tax-exempt, comparing the coupon rates of municipal bonds to corporate or other taxable bonds can be misleading. Taxes reduce the net income on taxable bonds, meaning that a tax-exempt municipal bond has a higher after-tax yield than a corporate bond with the same coupon rate.

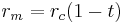

This relationship can be demonstrated mathematically, as follows:

where

- rm = interest rate of municipal bond

- rc = interest rate of comparable corporate bond

- t = tax rate

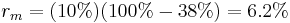

For example if rc = 10% and t = 38%, then

A municipal bond that pays 6.2% therefore generates equal interest income after taxes as a corporate bond that pays 10% (assuming all else is equal).

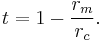

The marginal tax rate t at which an investor is indifferent between holding a corporate bond yielding rc and a municipal bond yielding rm is:

All investors facing a marginal rate greater than t are better off investing in the municipal bond than in the corporate bond.

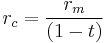

Alternatively, one can calculate the taxable equivalent yield of a municipal bond and compare it to the yield of a corporate bond as follows:

Because longer maturity municipal bonds tend to offer significantly higher after-tax yields than corporate bonds with the same credit rating and maturity, investors in higher tax brackets may be motivated to arbitrage municipal bonds against corporate bonds using a strategy called municipal bond arbitrage.

Some municipal bonds are insured by monoline insurers that take on the credit risk of these bonds for a small fee.

Subprime mortgage crisis

The municipal bond market was affected by the subprime mortgage crisis. During the crisis, monoline insurers that insured municipal bonds incurred heavy losses on the collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) and other structured financial products that they also insured. Consequently, the credit ratings of these monoline insurers were called into question, and the prices of municipal bonds fell.

Default rates

The historical default rate for municipal bonds is lower than that of corporate bonds. The Municipal Bond Fairness Act (HR 6308),[4] introduced September 9, 2008, included the following table giving bond default rates up to 2007 for municipal versus corporate bonds by rating and rating agency.

Cumulative historic default rates (in percent)

------------------------------------------------------------------------

Moody's S&P

Rating categories ---------------------------------------

Muni Corp Muni Corp

------------------------------------------------------------------------

Aaa/AAA......................... 0.00 0.52 0.00 0.60

Aa/AA........................... 0.06 0.52 0.00 1.50

A/A............................. 0.03 1.29 0.23 2.91

Baa/BBB......................... 0.13 4.64 0.32 10.29

Ba/BB........................... 2.65 19.12 1.74 29.93

B/B............................. 11.86 43.34 8.48 53.72

Caa-C/CCC-C..................... 16.58 69.18 44.81 69.19

Investment grade................ 0.07 2.09 0.20 4.14

Non-invest grade................ 4.29 31.37 7.37 42.35

All............................. 0.10 9.70 0.29 12.98

------------------------------------------------------------------------

Build America Bonds

Build America Bonds are a taxable municipal bond created under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 that carry special tax credits and federal subsidies for either the bond holder or the bond issuer. Many issuers have taken advantage of the Build America Bond provision to secure financing at a lower cost than issuing traditional tax-exempt bonds. The Build America Bond provision is open to governmental agencies issuing capital expenditure bonds before January 1, 2011.[5][6][7]

Statutory history

The U.S. Supreme Court held in 1895 that the federal government had no power under the U.S. Constitution to tax interest on municipal bonds.[8] But, in 1988, the Supreme Court stated the Congress could tax interest income on municipal bonds if it so desired on the basis that tax exemption of municipal bonds is not protected by the Constitution.[9] In this case, the Supreme Court stated that the contrary decision of the Court 1895 in the case of Pollock v. Farmers' Loan & Trust Co. had been "effectively overruled by subsequent case law."

The Revenue Act of 1913 first codified exemption of interest on municipal bonds from federal income tax.[10]

The Tax Reform Act of 1986 greatly reduced private activities that may be financed with tax-exempt bond proceeds.[11]

IRC 103(a) is the statutory provision that excludes interest on municipal bonds from federal income tax.[12] As of 2004[update], other rules, however, such as those pertaining to private activity bonds, are found in sections 141–150, 1394, 1400, 7871.

References

- ^ Temal, Judy Wesalo (2001). The Fundamentals of Municipal Bonds: The Bond Market Association. John Wiley and Sons, Inc.. p. 49. ISBN 0-471-39365-7.

- ^ Tax regulations

- ^ http://www.marksmarketanalysis.com/2010/09/harrisburg-to-weigh-hiring-bankruptcy.html

- ^ http://frwebgate.access.gpo.gov/cgi-bin/getdoc.cgi?dbname=110_cong_reports&docid=f:hr835.110

- ^ DerivActiv MuniMarket Pulse. "Mier of Loop Capital Says an Issuer 'Can Get Access to All These New Buyers by Going Taxable'" Retrieved on May 23, 2009

- ^ Internal Revenue Service. "IRS Issues Guidance on New Build America Bonds" Retrieved on May 23, 2009.

- ^ Rosenberg, Stan. "Louisiana Joins Build America Bond Parade With $121 Million" Wall Street Journal. May 27, 2009. Retrieved on May 31, 2009.

- ^ Pollock v. Farmers' Loan & Trust Co., 157 U.S. 429, 15 S. Ct. 673, 39 L. Ed. 759 (1895)

- ^ South Carolina v. Baker, 485 U.S. 505, 108 S. Ct. 1355, 99 L. Ed. 2d 592 (1988)

- ^ Revenue Act of 1913

- ^ Tax Reform Act of 1986

- ^ IRC 103(a).

External links

- http://www.citymayors.com/finance/bonds.html Municipal bonds have been issued by US local governments since 1812

- MSRB's EMMA Education Center

- The Bond Buyer, newspaper focusing on the municipal bond industry.

- MuniMarket Pulse Podcast, The only podcast dedicated to Municipal Bond Market News and Commentary

- Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association, the industry trade group.

- Municipal Finance Journal, the only peer-reviewed journal devoted to municipal securities and state & local public finance.

- About Municipal Bonds

- List of German Municipal Dollar Gold Bonds

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||