Moment of inertia

In classical mechanics, moment of inertia, also called mass moment of inertia, rotational inertia, polar moment of inertia of mass, or the angular mass, (SI units kg·m²) is a measure of an object's resistance to changes to its rotation. It is the inertia of a rotating body with respect to its rotation. The moment of inertia plays much the same role in rotational dynamics as mass does in linear dynamics, describing the relationship between angular momentum and angular velocity, torque and angular acceleration, and several other quantities. The symbol I and sometimes J are usually used to refer to the moment of inertia or polar moment of inertia.

While a simple scalar treatment of the moment of inertia suffices for many situations, a more advanced tensor treatment allows the analysis of such complicated systems as spinning tops and gyroscopic motion.

The concept was introduced by Leonhard Euler in his book Theoria motus corporum solidorum seu rigidorum in 1765.[1] In this book, he discussed the moment of inertia and many related concepts, such as the principal axis of inertia.

Contents |

Overview

The moment of inertia of an object about a given axis describes how difficult it is to change its angular motion about that axis. Therefore, it encompasses not just how much mass the object has overall, but how far each bit of mass is from the axis. The further out the object's mass is, the more rotational inertia the object has, and the more torque (force* distance from axis of rotation) is required to change its rotation rate. For example, consider two hoops, A and B, made of the same material and of equal mass. Hoop A is larger in diameter but thinner than B. It requires more effort to accelerate hoop A (change its angular velocity) because its mass is distributed farther from its axis of rotation: mass that is farther out from that axis must, for a given angular velocity, move more quickly than mass closer in. So in this case, hoop A has a larger moment of inertia than hoop B.

The moment of inertia of an object can change if its shape changes. Figure skaters who begin a spin with arms outstretched provide a striking example. By pulling in their arms, they reduce their moment of inertia, causing them to spin faster (by the conservation of angular momentum).

The moment of inertia has two forms, a scalar form, I, (used when the axis of rotation is specified) and a more general tensor form that does not require the axis of rotation to be specified. The scalar moment of inertia, I, (often called simply the "moment of inertia") allows a succinct analysis of many simple problems in rotational dynamics, such as objects rolling down inclines and the behavior of pulleys. For instance, while a block of any shape will slide down a frictionless decline at the same rate, rolling objects may descend at different rates, depending on their moments of inertia. A hoop will descend more slowly than a solid disk of equal mass and radius because more of its mass is located far from the axis of rotation. However, for (more complicated) problems in which the axis of rotation can change, the scalar treatment is inadequate, and the tensor treatment must be used (although shortcuts are possible in special situations). Examples requiring such a treatment include gyroscopes, tops, and even satellites, all objects whose alignment can change.

The moment of inertia is also called the mass moment of inertia (especially by mechanical engineers) to avoid confusion with the second moment of area, which is sometimes called the area moment of inertia (especially by structural engineers). The easiest way to differentiate these quantities is through their units (kg·m² as opposed to m4). In addition, moment of inertia should not be confused with polar moment of inertia (more specifically, polar moment of inertia of area), which is a measure of an object's ability to resist torsion (twisting) only, although, mathematically, they are similar: if the solid for which the moment of inertia is being calculated has uniform thickness in the direction of the rotating axis, and also has uniform mass density, the difference between the two types of moments of inertia is a factor of mass per unit area.

Scalar moment of inertia for single body

Consider a massless rigid rod of length  with a point mass

with a point mass  at one end and rotating about the other end. Suppose the rod rotates at a constant rate so that the mass moves at speed

at one end and rotating about the other end. Suppose the rod rotates at a constant rate so that the mass moves at speed  . Then the kinetic energy

. Then the kinetic energy  of the mass is:

of the mass is:

Using  , where ω is the angular velocity, one obtains:

, where ω is the angular velocity, one obtains:

which can be rearranged to give:

This equation resembles the original expression for the kinetic energy, but in the place of the linear velocity  is the angular velocity

is the angular velocity  , and instead of the mass

, and instead of the mass  is

is  . The quantity

. The quantity  can therefore be seen as an analogue of mass for rotational motion; in other words, it is a measure of rotational inertia.

can therefore be seen as an analogue of mass for rotational motion; in other words, it is a measure of rotational inertia.

Scalar moment of inertia for many bodies

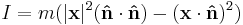

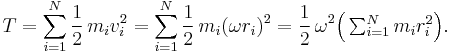

Consider a rigid body rotating with angular velocity ω around a certain axis. The body consists of N point masses mi whose distances to the axis of rotation are denoted ri. Each point mass will have the speed vi = ωri, so that the total kinetic energy T of the body can be calculated as

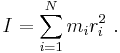

In this expression the quantity in parentheses is called the moment of inertia of the body (with respect to the specified axis of rotation). It is a purely geometric characteristic of the object, as it depends only on its shape and the position of the rotation axis. The moment of inertia is usually denoted with the capital letter I:

It is worth emphasizing that ri here is the distance from a point to the axis of rotation, not to the origin. As such, the moment of inertia will be different when considering rotations about different axes.

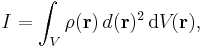

Similarly, the moment of inertia of a continuous solid body rotating about a known axis can be calculated by replacing the summation with the integral:

where r is the radius vector of a point within the body, ρ(r) is the mass density at point r, and d(r) is the distance from point r to the axis of rotation. The integration is evaluated over the volume V of the body.

Moment of inertia about a point

In discussions of the virial theorem, a different definition of moment of inertia is introduced, often qualified as moment of inertia about a point (as opposed to an axis). The defining equations look the same as the ones above, but  and

and  in these cases are understood to be the distance to the origin.

in these cases are understood to be the distance to the origin.

Moment of inertia theorems

Calculations for the moment of inertia (MOI) of a body are not easy in general. The process can be simplified in the following ways:

- Choosing axes to take advantage of geometric symmetries

- Physical homeogeneity (i.e. uniform mass distribution) making the density function ρ(r) become constant (elementary calculations, or generally an approximation)

- Use of the following theorems[2], see below for details.

| Theorem | Nomenclature | Equation |

|---|---|---|

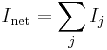

| Superposition Principle for MOI about any chosen Axis |

Inet = Resultant MOI (about any one axis) |  |

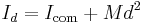

| Parallel axis theorem | M = Total mass of body d = Perpendicular distance from an axis |

|

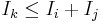

| Perpendicular axis theorem | i, j, k refer to MOI about any three mutually perpendicular axes. The sum of MOI about any two is greater than |

|

Properties

Superposition

The moment of inertia of the body is additive. That is, if a body can be decomposed (either physically or conceptually) into several constituent parts, then the moment of inertia of the whole body about a given axis is equal to the sum of moments of inertia of each part around the same axis.[3]

Basing just on the dimensional analysis, the moment of inertia must take the form I = c·M·L2, where M is the mass, L is the “size” of the body in the direction perpendicular to the axis of rotation, and c is a dimensionless inertial constant. Additionally, the length  is called the radius of gyration of the body.

is called the radius of gyration of the body.

Perpendicular Axes

If Ix, Iy, Iz are moments of inertia around three perpendicular axes passing through the body’s center of mass, then each of them cannot be greater than the sum of two others: for example Iz ≤ Ix + Iy. Here the equality holds only if the body is flat and located in the Oxy coordinate plane.

Parallel Axes

If the object’s moment of inertia ICOM around a certain axis passing through the center of mass is known, then the parallel axis theorem or Huygens–Steiner theorem provides a convenient formula to compute the moment of inertia Id of the same body around a different axis, which is parallel to the original and located at a distance d from it. The formula is only suitable when the initial and final axes are parallel. In order to compute the moment of inertia about an arbitrary axis, one has to use the object’s moment of inertia tensor.

Energy, angular momentum, torque

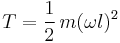

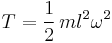

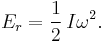

The rotational kinetic energy of a rigid body with angular velocity ω (in radians per second) is expressed in terms of the object’s moment of inertia:

This formula is similar to the translational kinetic energy Et = ½mv 2. Thus, the moment of inertia I plays the role of mass in rotational dynamics. One key difference between the mass and the (scalar) moment of inertia is that the latter depends on the axis of rotation and so is not truly invariant. The invariant characteristic of the body in rotational motion is the tensor of moment of inertia I, defined later.

The angular momentum of the body rotating around one of its principal axes is also proportional to the moment of inertia:

This expression is parallel to the formula for translational momentum p = mv, where the moment of inertia I plays the role of mass m, and the angular velocity ω stands for the velocity v. The scalar formula is valid for rotations around one of the principal axes of the body or for rotation about any fixed axis. The equivalent formula involving the tensor moment of inertia is always correct and must be used in cases of free rotation about a non-principal axis.

Also when the body rotates around one of its principal axes, and the direction of the axis of rotation remains constant, one can relate the torque on an object and its angular acceleration in a similar equation:

where τ is the torque and α is the angular acceleration.

Examples

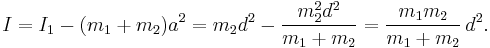

Diatomic molecule, with atoms m1 and m2 at a distance d from each other, rotating around the axis which passes through the molecule’s center of mass and is perpendicular to the direction of the molecule.

The easiest way to calculate this molecule’s moment of inertia is to use the parallel axis theorem. If we consider rotation around the axis passing through the atom m1, then the moment of inertia will be I1 = m1·0 + m2·d 2 = m2d 2. On the other hand, by the parallel axis theorem this moment is equal to I1 = I + (m1 + m2)·a 2, where I is the moment of inertia around the axis passing through the center of mass, and a is the distance between the center of mass and the first atom. By the center of mass formula, this distance is equal to a = m2 d / (m1 + m2). Thus,

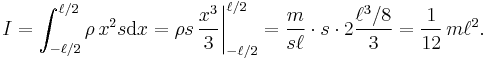

Thin rod of mass m and length ℓ, rotating around the axis which passes through its center and is perpendicular to the rod.

Let Oz be the axis of rotation, and Ox the axis along the rod. If ρ is the density, and s the cross-section of the rod (so that m = ρℓs), then the volume element for the integral formula will be equal to dV = s·dx, where x changes from −½ℓ to ½ℓ. The moment of inertia can be found by computing the integral:

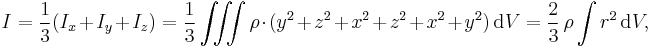

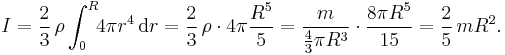

Solid ball of mass m and radius R, rotating around an axis which passes through the center.

Suppose Oz is the axis of rotation. The distance from point r = (x, y, z) towards the axis Oz is equal to d(r)2 = x 2 + y 2. Thus, in order to compute the moment of inertia Iz, we need to evaluate the integral ∭(x 2 + y 2) dV. The calculation considerably simplifies if we notice that by symmetry of the problem, the moments of inertia around all axes are equal: Ix = Iy = Iz. Then

where r2 = x 2 + y 2 + z2 is the distance from point r to the origin. This integral is easy to evaluate in the spherical coordinates, the volume element will be equal to dV = 4πr 2 dr, where r goes from 0 to R. Thus,

In mechanics of machines, when designing rotary parts like gears, pulleys, shafts, couplings etc., which are used to transmit torques, the moment of inertia has to be considered. The moment of inertia is given about an axis and it depends on the shape, density of a rotating element.

When considering mechanisms like gear trains, worm and wheel, where there are more than one rotating element, more than one axis of rotation, an equivalent moment of inertia for the system should be found. Practically when a geared system is enclosed, equivalent moment of inertia can be measured by measuring the angular acceleration for a known torque or theoretically it can be estimated when the masses and dimensions of the rotating elements and shafts are known. In this practical the equivalent moment of inertia of a worm and wheel system is measured using above mention methods.

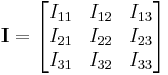

Moment of inertia tensor

In three dimensions, if the axis of rotation is not given, we need to be able to generalize the scalar moment of inertia to a quantity that allows us to compute a moment of inertia about arbitrary axes. This quantity is known as the moment of inertia tensor and can be represented as a symmetric positive semi-definite matrix, I. This representation elegantly generalizes the scalar case: The angular momentum vector is related to the rotation velocity vector ω by

and the kinetic energy is given by

as compared with

in the scalar case.

Like the scalar moment of inertia, the moment of inertia tensor may be calculated with respect to any point in space, but for practical purposes, the center of mass is almost always used. In general, its components are time dependent.

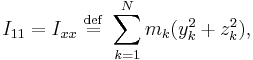

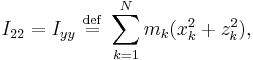

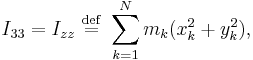

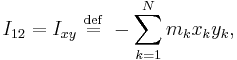

Definition

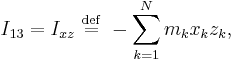

For a rigid object of  point masses

point masses  , the moment of inertia tensor (with respect to the origin) has components given by

, the moment of inertia tensor (with respect to the origin) has components given by

,

,

where

and  ,

,  , and

, and  . (Thus

. (Thus  is a symmetric tensor.) Note that the scalars

is a symmetric tensor.) Note that the scalars  with

with  are called the products of inertia.

are called the products of inertia.

Here  denotes the moment of inertia around the

denotes the moment of inertia around the  -axis when the objects are rotated around the x-axis,

-axis when the objects are rotated around the x-axis,  denotes the moment of inertia around the

denotes the moment of inertia around the  -axis when the objects are rotated around the

-axis when the objects are rotated around the  -axis, and so on.

-axis, and so on.

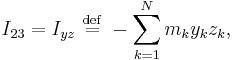

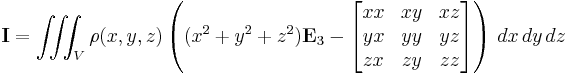

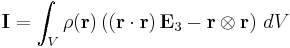

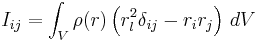

These quantities can be generalized to an object with distributed mass, described by a mass density function, in a similar fashion to the scalar moment of inertia. One then has

In more-concise notation:

where  is the vector from the center of mass to a point in the volume, V and

is the vector from the center of mass to a point in the volume, V and  is their outer product, E3 is the 3 × 3 identity matrix, and V is a region of space completely containing the object. Alternatively, the above can be described in Einstein notation as:

is their outer product, E3 is the 3 × 3 identity matrix, and V is a region of space completely containing the object. Alternatively, the above can be described in Einstein notation as:

where  is the Kronecker delta.

is the Kronecker delta.

The diagonal elements of  are called the principal moments of inertia.

are called the principal moments of inertia.

As is clear from the definition,  and its components are in general time-dependent. They are constant only if calculated in a reference frame moving rigidly with the rigid body. On the other hand, the eigenvalues

and its components are in general time-dependent. They are constant only if calculated in a reference frame moving rigidly with the rigid body. On the other hand, the eigenvalues  are invariant, that is independent of the reference frame used to calculate

are invariant, that is independent of the reference frame used to calculate  .

.

Derivation of the tensor components

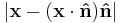

The distance  of a particle at

of a particle at  from the axis of rotation passing through the origin in the

from the axis of rotation passing through the origin in the  direction is

direction is  . By using the formula

. By using the formula  (and some simple vector algebra) it can be seen that the moment of inertia of this particle (about the axis of rotation passing through the origin in the

(and some simple vector algebra) it can be seen that the moment of inertia of this particle (about the axis of rotation passing through the origin in the  direction) is

direction) is  This is a quadratic form in

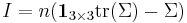

This is a quadratic form in  and, after a bit more algebra, this leads to a tensor formula for the moment of inertia

and, after a bit more algebra, this leads to a tensor formula for the moment of inertia

![{I} = m [n_1\,n_2\,n_3]\begin{bmatrix}

y^2%2Bz^2 & -xy & -xz \\

-y x & x^2%2Bz^2 & -yz \\

-zx & -zy & x^2%2By^2

\end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix}

n_1 \\

n_2\\

n_3

\end{bmatrix}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/bea0409c9dbee072367378e93b62714b.png) .

.

This is exactly the formula given below for the moment of inertia in the case of a single particle. For multiple particles we need only recall that the moment of inertia is additive in order to see that this formula is correct.

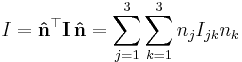

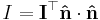

Reduction to scalar

For any axis  , represented as a column vector with elements ni, the scalar form I can be calculated from the tensor form I as

, represented as a column vector with elements ni, the scalar form I can be calculated from the tensor form I as

The range of both summations correspond to the three Cartesian coordinates.

The following equivalent expression avoids the use of transposed vectors which are not supported in maths libraries because internally vectors and their transpose are stored as the same linear array,

However it should be noted that although this equation is mathematically equivalent to the equation above for any matrix, inertia tensors are symmetrical. This means that it can be further simplified to:

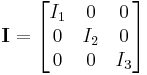

Principal axes of inertia

By the spectral theorem, since the moment of inertia tensor is real and symmetric, there exists a Cartesian coordinate system in which it is diagonal, having the form

where the coordinate axes are called the principal axes and the constants  ,

,  and

and  are called the principal moments of inertia.

are called the principal moments of inertia.

This result was first shown by J. J. Sylvester (1852), and is a form of Sylvester's law of inertia. The principal axis with the highest moment of inertia is sometimes called the figure axis or axis of figure.

When all principal moments of inertia are distinct, the principal axes through center of mass are uniquely specified. If two principal moments are the same, the rigid body is called a symmetrical top and there is no unique choice for the two corresponding principal axes. If all three principal moments are the same, the rigid body is called a spherical top (although it need not be spherical) and any axis can be considered a principal axis, meaning that the moment of inertia is the same about any axis.

The principal axes are often aligned with the object's symmetry axes. If a rigid body has an axis of symmetry of order  , meaning it is symmetrical under rotations of 360°/m about the given axis, that axis is a principal axis. When

, meaning it is symmetrical under rotations of 360°/m about the given axis, that axis is a principal axis. When  , the rigid body is a symmetrical top. If a rigid body has at least two symmetry axes that are not parallel or perpendicular to each other, it is a spherical top, for example, a cube or any other Platonic solid.

, the rigid body is a symmetrical top. If a rigid body has at least two symmetry axes that are not parallel or perpendicular to each other, it is a spherical top, for example, a cube or any other Platonic solid.

The motion of vehicles is often described about these axes with the rotations called yaw, pitch, and roll.

A practical example of this mathematical phenomenon is the routine automotive task of balancing a tire, which basically means adjusting the distribution of mass of a car wheel such that its principal axis of inertia is aligned with the axle so the wheel does not wobble.

Parallel axis theorem

Once the moment of inertia tensor has been calculated for rotations about the center of mass of the rigid body, there is a useful labor-saving method to compute the tensor for rotations offset from the center of mass.

If the axis of rotation is displaced by a vector R from the center of mass, the new moment of inertia tensor equals

where m is the total mass of the rigid body, E3 is the 3 × 3 identity matrix, and  is the outer product.

is the outer product.

Rotational symmetry

Using the above equation to express all moments of inertia in terms of integrals of variables either along or perpendicular to the axis of symmetry usually simplifies the calculation of these moments considerably.

Comparison with covariance matrix

The moment of inertia tensor about the center of mass of a 3 dimensional rigid body is related to the covariance matrix of a trivariate random vector whose probability density function is proportional to the pointwise density of the rigid body by:

where n is the number of points.

The structure of the moment-of-inertia tensor comes from the fact that it is to be used as a bilinear form on rotation vectors in the form

Each element of mass has a kinetic energy of

The velocity of each element of mass is ω × r where r is a vector from the center of rotation to that element of mass. The cross product can be converted to matrix multiplication so that

and similarly

Thus,

plugging in the definition of ![[\cdot]_\times](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/13500ce53c18a4912d92f5e3a9d88281.png) the

the ![[r]_\times^\top [r]_\times](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/9116002cef17aefae446be4ce3f317a3.png) term leads directly to the structure of the moment tensor.

term leads directly to the structure of the moment tensor.

See also

- List of moments of inertia

- List of moment of inertia tensors

- Rotational energy

- Parallel axis theorem

- Perpendicular axis theorem

- Stretch rule

- Tire balance

- Poinsot's ellipsoid

- Instant centre of rotation

Notes

- ^ Euler, Leonhard (1765-01-01) (in Latin), Theoria motus corporum solidorum seu rigidorum: Ex primis nostrae cognitionis principiis stabilita et ad omnes motus, qui in huiusmodi corpora cadere possunt, accommodata, Cornell University Library, ISBN 978-1429742818

- ^ 3000 Solved Problems in Physics, Schaum Series, A. Halpern, Mc Graw Hill, 1988, ISBN 9-780070-257344

- ^ “Mass moment of inertia” by Mehrdad Negahban, University of Nebraska

References

- Goldstein, H. (1980). Classical Mechanics (2nd ed.). Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-201-02918-9..

- Landau, LD; Lifshitz (1976). Mechanics (3rd ed.). Pergamon Press. ISBN 0-080-21022-8 (hardcover).; ISBN 0-080-29141-4 (softcover).

- Marion, JB; Thornton, ST. (1995). Classical Dynamics of Systems and Particles (4th ed.). Thomson. ISBN 0-030-97302-3..

- Sylvester, J J (1852), "A demonstration of the theorem that every homogeneous quadratic polynomial is reducible by real orthogonal substitutions to the form of a sum of positive and negative squares", Philosophical Magazine IV: 138–142, http://www.maths.ed.ac.uk/~aar/sylv/inertia.pdf, retrieved 2008-06-27

- Symon, KR (1971). Mechanics (3rd ed.). Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-201-07392-7..

- Tenenbaum, RA (2004). Fundamentals of Applied Dynamics. Springer. ISBN 0-387-00887-X..

External links

- Angular momentum and rigid-body rotation in two and three dimensions

- Lecture notes on rigid-body rotation and moments of inertia

- The moment of inertia tensor

- An introductory lesson on moment of inertia: keeping a vertical pole not falling down (Java simulation)

- Tutorial on finding moments of inertia, with problems and solutions on various basic shapes

- Testing Facilities for the Moment of Inertia Rig at Cranfield Impact Centre

![\mathbf{I}^{\mathrm{displaced}} = \mathbf{I}^{\mathrm{center}} %2B m \left[\left(\mathbf{R} \cdot \mathbf{R}\right) \mathbf{E}_{3} - \mathbf{R} \otimes \mathbf{R} \right]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/5685f05491ff00428551ec8ad91b5de0.png)

![\omega\times r = [r]_\times^\top \omega\,\!](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/094bf7983509e9ef849a52534a1e5ee6.png)

![(\omega\times r)^\top = ([r]_\times \omega)^\top = \omega^\top [r]_\times^\top \,\!](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/8d51101272f20bcd01f2a96e337296ca.png)

![|v|^2 = (\omega\times r)^\top(\omega\times r)=\omega^\top [r]_\times^\top [r]_\times \omega \,\!](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/815aafeec20d88b72a01c19a50ad055e.png)