Molality

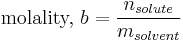

In chemistry, the molality, b (or m), of a solvent/solute combination is defined as the amount of solute,  , divided by the mass of the solvent,

, divided by the mass of the solvent,  (not the mass of the solution):[1]

(not the mass of the solution):[1]

If a mixture contains more than one solute or solvent, each solvent/solute combination in the mixture is defined in this same way.

Contents |

Origin

The earliest such definition of the intensive property molality and of its adjectival unit, the now-deprecated molal (formerly, a variant of molar, describing a solution of unit molar concentration), appear to have been coined by G. N. Lewis and M. Randall in their 1923 publication of Thermodynamics and the Free Energies of Chemical Substances.[2] Though the two words are subject to being confused with one another, the molality and molarity of a weak aqueous solution happen to be nearly the same, as one kilogram of water (the solvent) occupies 1 liter of volume at room temperature and the small amount of solute would have little effect on the volume.

Unit

The SI unit for molality is mol/kg.

A solution with a molality of 3 mol/kg is often described as "3 molal" or "3 m". However, following the SI system of units, the National Institute of Standards and Technology, the United States authority on measurement, considers the term "molal" and the unit symbol "m" to be obsolete, and suggests mol/kg or a related unit of the SI.[3] This recommendation has not been universally implemented in academia yet.

Example

Dissolving 1.0 mol of table salt (NaCl) in 2.0 kg of water constitutes a solution with a molality of m(NaCl) = 0.50 mol/kg. Adding and dissolving sugar to the solution does not change the molality of NaCl.

Usage considerations

Advantages:

Compared to molar concentration or mass concentration, the preparation of a solution of a given molality requires only a good scale: both solvent and solute need to be weighed, as opposed to measured volumetrically, which would be subject to variations in density due to the ambient conditions of temperature and pressure; this is an advantage because, in chemical compositions, the mass, or the amount, of a pure known substance is more relevant than its volume: a contained measured amount of substance may change in volume with ambient conditions, but its amount and mass are unvarying, and chemical reactions occur in proportions of mass, not volume. The mass-based nature of molality implies that it can be readily converted into a mass ratio (or mass fraction, "w," ratio),

where the symbol M stands for molar mass, or into a mole ratio (or mole fraction, "x," ratio)

The advantage of molality over other mass-based fractions is the fact that the molality of one solute in a single-solvent solution is independent of the presence or absence of other solutes.

Problem areas:

Unlike all the other compositional properties listed in "Relation" section (below), molality depends on our choice of the substance we call “solvent” in an arbitrary mixture. If there is only one pure liquid substance in a mixture, the choice is clear, but not all solutions are this clear-cut: in an alcohol-water solution, either one could be called the solvent; in an alloy, or solid solution, there is no clear choice and all constituents may be treated alike. In such situations, mass or mole fraction is the preferred compositional specification.

Relation to other compositional properties

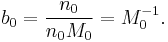

In what follows, the solvent may be given the same treatment as the other constituents of the solution, such that the molality of the solvent of an n-solute solution, say b0, is found to be nothing more than the reciprocal of its molar mass, M0:

Mass fraction

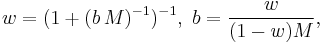

The conversions to and from the mass fraction,  , of the solute in a single-solute solution are

, of the solute in a single-solute solution are

where b is the molality and M is the molar mass of the solute.

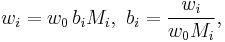

More generally, for an n-solute/one-solvent solution, letting bi and wi be, respectively, the molality and mass fraction of the i-th solute,

where Mi is the molar mass of the i-th solute, and w0 is the mass fraction of the solvent, which is expressible both as a function of the molalities as well as a function of the other mass fractions,

Mole fraction

The conversions to and from the mole fraction, x, of the solute in a single-solute solution are

where M0 is the molar mass of the solvent.

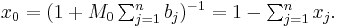

More generally, for an n-solute/one-solvent solution, letting xi be the mole fraction of the i-th solute,

where x0 is the mole fraction of the solvent, expressible both as a function of the molalities as well as a function of the other mole fractions:

Molar concentration (Molarity)

The conversions to and from the molar concentration, c, for one-solute solutions are

where ρ is the mass density of the solution, b is the molality, and M is the molar mass of the solute.

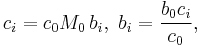

For solutions with n solutes, the conversions are

where the molar concentration of the solvent c0 is expressible both as a function of the molalities as well as a function of the molarities:

Mass concentration

The conversions to and from the mass concentration, ρsolute, of an single-solute solution are

where ρ is the mass density of the solution, b is the molality, and M is the molar mass of the solute.

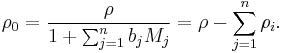

For the general n-solute solution, the mass concentration of the i-th solute, ρi, is related to its molality, bi, as follows:

where the mass concentration of the solvent, ρ0, is expressible both as a function of the molalities as well as a function of the mass concentrations:

Equal ratios

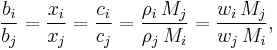

Alternatively, we may use just the last two equations given for the compositional property of the solvent in each of the preceding sections, together with the relationships given below, to derive the remainder of properties in that set:

where i and j are subscripts representing all the constituents, the n solutes plus the solvent.

Example of conversion

An acid mixture consists of 0.76/0.04/0.20 mass fractions of (70% HNO3)/(49% HF)/(H2O), where the percentages refer to mass fractions of the bottled acids carrying a balance of H2O. The first step is determining the mass fractions of the constituents:

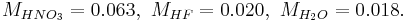

The approximate molar masses in kg/mol are

First derive the molality of the solvent, in mol/kg,

and use that to derive all the others by use of the equal ratios:

Actually, bH2O cancels out, because it is not needed. In this case, there is a more direct equation: we use it to derive the molality of HF:

The mole fractions may be derived from this result:

References

- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book") (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) "molality".

- ^ www.OED.com. Oxford University Press. 2011.

- ^ "NIST Guide to SI Units". http://physics.nist.gov/Pubs/SP811/sec11.html. Retrieved 2007-12-17.

|

||||||||||||||