Microrheology

Microrheology[1] is a technique to measure the rheological properties of a medium, such as microviscosity, via the measurement of the trajectory of a flow tracer (a micrometre-size particle). It is a new way of doing rheology, traditionally done using a rheometer. The size of the tracer is around a micrometre. There are two types of microrheology: passive microrheology and active microrheology. Passive microrheology uses inherent thermal energy to move the tracers, whereas active microrheology uses externally applied forces, such as from a magnetic field or an optical tweezer, to do so. Microrheology can be further differentiated into 1- and 2-particle methods[2] [3].

Contents |

Passive microrheology

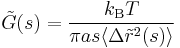

Passive microrheology uses the thermal energy (kT) to move the tracers. The trajectories of the tracers are measured optically either by microscopy or by diffusing-wave spectroscopy (DWS). From the mean square displacement with respect to time (noted MSD or <Δr2> ), one can calculate the visco-elastic moduli G′(ω) and G″(ω) using the generalized Stokes–Einstein relation (GSER). Here is a view of the trajectory of a particle of micrometer size.

Observing the MSD for a wide range of time scales gives information on the microstructure of the medium where are diffusing the tracers. If the tracers are having a free diffusion, on can deduce that the medium is purely viscous. If the tracers are having a sub-diffusive mean trajectory, it indicates that the medium presents some viscoelastic properties. For example, in a polymer network, the tracer may be trapped. The excursion δ of the tracer is related to the elastic modulus G′ with the relation G′ = kBT/(6πaδ2).[4]

Microrheology is another way to do linear rheology. Since the force involved is very weak (order of 10−15 N), microrheology is guaranteed to be in the so-called linear region of the strain/stress relationship. It is also able to measure very small volumes (biological cell).

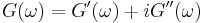

Given the complex viscoelastic modulus  with G′(ω) dissipative part and G″(ω) the conservative part and ω=2πf the pulsation. The GSER is as follow:

with G′(ω) dissipative part and G″(ω) the conservative part and ω=2πf the pulsation. The GSER is as follow:

with

: Laplace transform of G

: Laplace transform of G- kB: Boltzmann constant

- T: temperature in kelvins

- s: the Laplace frequency

- a: the radius of the tracer

: the Laplace transform of the mean square displacement

: the Laplace transform of the mean square displacement

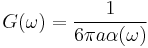

A related method of passive microrheology involves the tracking positions of a particle at a high frequency, often with a quadrant photodiode[5]. From the position,  , the power spectrum,

, the power spectrum,  can be found, and then related to the real and imaginary parts of the response function,

can be found, and then related to the real and imaginary parts of the response function,  [6]. The response function leads directly to a calculation of the complex shear modulus,

[6]. The response function leads directly to a calculation of the complex shear modulus,  via:

via:

Active microrheology

Active microrheology may use a magnetic field [7][8][9][10][11] or optical tweezers[12] to apply a force on the tracer and then find the stress/strain relation.

References

- ^ Mason Weitz (1995). Physical Review Letters 74: 7.

- ^ Crocker, John C. and Valentine, M. T. and Weeks, Eric R. and Gisler, T. and Kaplan, P. D. and Yodh, A. G. and Weitz, D. A. (2000). "Two-Point Microrheology of Inhomogeneous Soft Materials". Physical Review Letters 85 (4): 888–891. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.888.

- ^ Levine, Alex J. and Lubensky, T. C. (2000). "One- and Two-Particle Microrheology". Physical Review Letters 85 (8): 1774–1777. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.1774.

- ^ European Physical Journal E 8: 431–436. 2002. Bibcode 2002EPJE....8..431B. doi:10.1140/epje/i2002-10026-0.

- ^ Schnurr, B. and Gittes, F. and MacKintosh, F. C. and Schmidt, C. F. (1997). "Determining Microscopic Viscoelasticity in Flexible and Semiflexible Polymer Networks from Thermal Fluctuations". Macromolecules 30 (25): 7781–7792. doi:10.1021/ma970555n.

- ^ Gittes, F. and Schnurr, B. and Olmsted, P. D. and MacKintosh, F. C. and Schmidt, C. F. (1997). "Determining Microscopic Viscoelasticity in Flexible and Semiflexible Polymer Networks from Thermal Fluctuations". Physical Review Letters 79 (17): 3286–3289. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.79.3286.

- ^ A.R. Bausch et al. (1999). "Measurement of local viscoelasticity and forces in living cells by magnetic tweezers". Biophysical Journal 76 (1 Pt 1): 573–9. Bibcode 1999BpJ....76..573B. doi:10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77225-5. PMC 1302547. PMID 9876170. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1302547.

- ^ K.S. Zaner and P.A. Valberg (1989). "Viscoelasticity of F-actin measured with magnetic microparticles". Journal of Cell Biology 109 (5): 2233–43. doi:10.1083/jcb.109.5.2233. PMC 2115855. PMID 2808527. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2115855.

- ^ F.Ziemann, J. Radler, and E. Sackmann (1994). "Local measurements of viscoelastic moduli of entangled actin networks using an oscillating magnetic bead micro-rheometer". Biophysical Journal 66 (6): 2210–6. Bibcode 1994BpJ....66.2210Z. doi:10.1016/S0006-3495(94)81017-3. PMC 1275947. PMID 8075354. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1275947.

- ^ F.G. Schmidt, F. Ziemann, and E. Sackmann (1996). European Biophysics Journal 24: 348.

- ^ F. Amblard et al. (1996). "Subdiffusion and Anomalous Local Viscoelasticity in Actin Networks". Physical Review Letters 77 (21): 4470–4473. Bibcode 1996PhRvL..77.4470A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.4470. PMID 10062546.

- ^ E. Helfer et al. (2000). "Microrheology of Biopolymer-Membrane Complexes". Physical Review Letters 85 (2): 457–60. Bibcode 2000PhRvL..85..457H. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.457. PMID 10991307.