Ludwig von Bertalanffy

| Ludwig von Bertalanffy | |

|---|---|

| Born | 19 September 1901 Vienna, Austria |

| Died | 12 June 1972 (aged 70) Buffalo, New York, USA |

| Fields | Biology and systems theory |

| Alma mater | University of Vienna |

| Known for | General System Theory |

| Influences | Rudolf Carnap, Gustav Theodor Fechner, Nicolai Hartmann, Otto Neurath, Moritz Schlick |

| Influenced | Russell L. Ackoff, Kenneth E. Boulding, Peter Checkland, C. West Churchman, Jay Wright Forrester, Ervin László, James Grier Miller, Anatol Rapoport |

Karl Ludwig von Bertalanffy (September 19, 1901, Atzgersdorf near Vienna, Austria – June 12, 1972, Buffalo, New York, USA) was an Austrian-born biologist known as one of the founders of general systems theory (GST). GST is an interdisciplinary practice that describes systems with interacting components, applicable to biology, cybernetics, and other fields. Bertalanffy proposed that the laws of thermodynamics applied to closed systems, but not necessarily to "open systems," such as living things. His mathematical model of an organism's growth over time, published in 1934, is still in use today.

Von Bertalanffy grew up in Austria and subsequently worked in Vienna, London, Canada and the USA.

Contents |

Biography

Ludwig von Bertalanffy was born and grew up in the little village of Atzgersdorf (now Liesing) near Vienna. The Bertalanffy family had roots in the 16th century nobility of Hungary which included several scholars and court officials.[1] His grandfather Charles Joseph von Bertalanffy (1833–1912) had settled in Austria and was a state theatre director in Klagenfurt, Graz, and Vienna, which were important positions in imperial Austria. Ludwig's father Gustav von Bertalanffy (1861–1919) was a prominent railway administrator. On his mother's side Ludwig's grandfather Joseph Vogel was an imperial counsellor and a wealthy Vienna publisher. Ludwig's mother Charlotte Vogel was seventeen when she married the thirty-four year old Gustav. They divorced when Ludwig was ten, and both remarried outside the Catholic Church in civil ceremonies.[2]

Ludwig von Bertalanffy grew up as an only child educated at home by private tutors until he was ten. When he went to the gymnasium/grammar school he was already well trained in self study, and kept studying on his own. His neighbour, the famous biologist Paul Kammerer, became a mentor and an example to the young Ludwig.[3] In 1918 he started his studies at the university level with the philosophy and art history, first at the University of Innsbruck and then at the University of Vienna. Ultimately, Bertalanffy had to make a choice between studying philosophy of science and biology, and chose the latter because, according to him, one could always become a philosopher later, but not a biologist. In 1926 he finished his PhD thesis (translated title: Fechner and the problem of integration of higher order) on the physicist and philosopher Gustav Theodor Fechner.[3]

Von Bertalanffy met his future wife Maria in April 1924 in the Austrian Alps, and were almost never apart for the next forty-eight years.[4] She wanted to finish studying but never did, instead devoting her life to Bertalanffy's career. Later in Canada she would work both for him and with him in his career, and after his death she compiled two of Bertalanffy's last works. They had one child, who would follow in his father's footsteps by making his profession in the field of cancer research.

Von Bertalanffy was a professor at the University of Vienna from 1934–48, University of London (1948–49), Université de Montréal (1949), University of Ottawa (1950–54), University of Southern California (1955–58), the Menninger Foundation (1958–60), University of Alberta (1961–68), and State University of New York at Buffalo (SUNY) (1969–72). In 1972, he died from a sudden heart attack.

Work

Today, Bertalanffy is considered to be a founder and one of the principal authors of the interdisciplinary school of thought known as general systems theory. According to Weckowicz (1989), he "occupies an important position in the intellectual history of the twentieth century. His contributions went beyond biology, and extended into cybernetics, education, history, philosophy, psychiatry, psychology and sociology. Some of his admirers even believe that this theory will one day provide a conceptual framework for all these disciplines".[1] Spending most of his life in semi-obscurity, Ludwig von Bertalanffy may well be the least known intellectual titan of the twentieth century.[5]

The individual growth model

The individual growth model published by von Bertalanffy in 1934 is widely used in biological models and exists in a number of permutations.

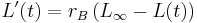

In its simplest version the so-called von Bertalanffy growth equation is expressed as a differential equation of length (L) over time (t):

when  is the von Bertalanffy growth rate and

is the von Bertalanffy growth rate and  the ultimate length of the individual. This model was proposed earlier by A. Pütter in 1920 (Arch. Gesamte Physiol. Mensch. Tiere, 180: 298-340).

the ultimate length of the individual. This model was proposed earlier by A. Pütter in 1920 (Arch. Gesamte Physiol. Mensch. Tiere, 180: 298-340).

The Dynamic Energy Budget theory provides a mechanistic explanation of this model in the case of isomorphs that experience a constant food availability. The inverse of the von Bertalanffy growth rate appears to depend linearly on the ultimate length, when different food levels are compared. The intercept relates to the maintenance costs, the slope to the rate at which reserve is mobilized for use by metabolism. The ultimate length equals the maximum length at high food availabilities.[6]

Bertalanffy Module

To honor Bertalanffy, ecological systems engineer and scientist Howard T. Odum named the storage symbol of his General Systems Language as the Bertalanffy module (see image right).[7]

General System Theory (GST)

The biologist is widely recognized for his contributions to science as a systems theorist; specifically, for the development of a theory known as General System Theory (GST). The theory attempted to provide alternatives to conventional models of organization. GST defined new foundations and developments as a generalized theory of systems with applications to numerous areas of study, emphasizing holism over reductionism, organism over mechanism.

Open systems

Bertalanffy's contribution to systems theory is best known for his theory of open systems. The system theorist argued that traditional closed system models based on classical science and the second law of thermodynamics were untenable. Bertalanffy maintained that “the conventional formulation of physics are, in principle, inapplicable to the living organism being open system having steady state. We may well suspect that many characteristics of living systems which are paradoxical in view of the laws of physics are a consequence of this fact.” [8] However, while closed physical systems were questioned, questions equally remained over whether or not open physical systems could justifiably lead to a definitive science for the application of an open systems view to a general theory of systems.

In Bertalanffy’s model, the theorist defined general principles of open systems and the limitations of conventional models. He ascribed applications to biology, information theory and cybernetics. Concerning biology, examples from the open systems view suggested they “may suffice to indicate briefly the large fields of application” that could be the “outlines of a wider generalization;” [9] from which, a hypothesis for cybernetics. Although potential applications exist in other areas, the theorist developed only the implications for biology and cybernetics. Bertalanffy also noted unsolved problems, which included continued questions over thermodynamics, thus the unsubstantiated claim that there are physical laws to support generalizations (particularly for information theory), and the need for further research into the problems and potential with the applications of the open system view from physics.

Systems in the social sciences

In the social sciences, Bertalanffy did believe that general systems concepts were applicable, e.g. theories that had been introduced into the field of sociology from a modern systems approach that included “the concept of general system, of feedback, information, communication, etc.” [10] The theorist critiqued classical “atomistic” conceptions of social systems and ideation “such as ‘social physics’ as was often attempted in a reductionist spirit.” [11] Bertalanffy also recognized difficulties with the application of a new general theory to social science due to the complexity of the intersections between natural sciences and human social systems. However, the theory still encouraged for new developments from sociology, to anthropology, economics, political science, and psychology among other areas. Today, Bertalanffy's GST remains a bridge for interdisciplinary study of systems in the social sciences.

See also

Publications

By Bertalanffy

- 1928, Kritische Theorie der Formbildung, Borntraeger. In English: Modern Theories of Development: An Introduction to Theoretical Biology, Oxford University Press, New York: Harper, 1933

- 1928, Nikolaus von Kues, G. Müller, München 1928.

- 1930, Lebenswissenschaft und Bildung, Stenger, Erfurt 1930

- 1937, Das Gefüge des Lebens, Leipzig: Teubner.

- 1940, Vom Molekül zur Organismenwelt, Potsdam: Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft Athenaion.

- 1949, Das biologische Weltbild, Bern: Europäische Rundschau. In English: Problems of Life: An Evaluation of Modern Biological and Scientific Thought, New York: Harper, 1952.

- 1953, Biophysik des Fliessgleichgewichts, Braunschweig: Vieweg. 2nd rev. ed. by W. Beier and R. Laue, East Berlin: Akademischer Verlag, 1977

- 1953, "Die Evolution der Organismen", in Schöpfungsglaube und Evolutionstheorie, Stuttgart: Alfred Kröner Verlag, pp 53–66

- 1955, "An Essay on the Relativity of Categories." Philosophy of Science, Vol. 22, No. 4, pp. 243–263.

- 1959, Stammesgeschichte, Umwelt und Menschenbild, Schriften zur wissenschaftlichen Weltorientierung Vol 5. Berlin: Lüttke

- 1962, Modern Theories of Development, New York: Harper

- 1967, Robots, Men and Minds: Psychology in the Modern World, New York: George Braziller, 1969 hardcover: ISBN 0-8076-0428-3, paperback: ISBN 0-8076-0530-1

- 1968, General System theory: Foundations, Development, Applications, New York: George Braziller, revised edition 1976: ISBN 0-8076-0453-4

- 1968, The Organismic Psychology and Systems Theory, Heinz Werner lectures, Worcester: Clark University Press.

- 1975, Perspectives on General Systems Theory. Scientific-Philosophical Studies, E. Taschdjian (eds.), New York: George Braziller, ISBN 0-8076-0797-5

- 1981, A Systems View of Man: Collected Essays, editor Paul A. LaViolette, Boulder: Westview Press, ISBN 0-86531-094-7

The first articles from Bertalanffy on General Systems Theory:

- 1945, Zu einer allgemeinen Systemlehre, Blätter für deutsche Philosophie, 3/4. (Extract in: Biologia Generalis, 19 (1949), 139-164.

- 1950, An Outline of General System Theory, British Journal for the Philosophy of Science 1, p. 139-164

- 1951, General system theory - A new approach to unity of science (Symposium), Human Biology, Dec 1951, Vol. 23, p. 303-361.

About Bertalanffy

- Sabine Brauckmann (1999). Ludwig von Bertalanffy (1901--1972), ISSS Luminaries of the Systemics Movement, January 1999.

- Peter Corning (2001). Fulfilling von Bertalanffy's Vision: The Synergism Hypothesis as a General Theory of Biological and Social Systems, ISCS 2001.

- Mark Davidson (1983). Uncommon Sense: The Life and Thought of Ludwig Von Bertalanffy, Los Angeles: J. P. Tarcher.

- Debora Hammond (2005). Philosophical and Ethical Foundations of Systems Thinking, tripleC 3(2): pp. 20–27. (Dead Link)

- Ervin László eds. (1972). The Relevance of General Systems Theory: Papers Presented to Ludwig Von Bertalanffy on His Seventieth Birthday, New York: George Braziller, 1972.

- David Pouvreau (2006). Une biographie non officielle de Ludwig von Bertalanffy (1901-1972), Vienna

- David Pouvreau & Manfred Drack (2007). On the history of Ludwig von Bertalanffy's "General Systemology", and on its relationship to cybernetics, in: International Journal of General Systems, Volume 36, Issue 3 June 2007, pages 281 - 337.

- Thaddus E. Weckowicz (1989). Ludwig von Bertalanffy (1901-1972): A Pioneer of General Systems Theory, Center for Systems Research Working Paper No. 89-2. Edmonton AB: University of Alberta, February 1989.

References

- ^ a b T.E. Weckowicz (1989). Ludwig von Bertalanffy (1901-1972): A Pioneer of General Systems Theory. Working paper Feb 1989. p.2

- ^ Mark Davidson (1983). Uncommon Sense: The Life and Thought of Ludwig Von Bertalanffy. Los Angeles: J. P. Tarcher. p.49

- ^ a b Bertalanffy Center for the Study of Systems Science, page: His Life - Bertalanffy's Origins and his First Education. Retrieved 2009-04-27

- ^ Davidson p.51

- ^ Davidson, p.9.

- ^ Bertalanffy, L. von, (1934). Untersuchungen über die Gesetzlichkeit des Wachstums. I. Allgemeine Grundlagen der Theorie; mathematische und physiologische Gesetzlichkeiten des Wachstums bei Wassertieren. Arch. Entwicklungsmech., 131:613-652.

- ^ Nicholas D. Rizzo William Gray (Editor), Nicholas D. Rizzo (Editor), (1973) Unity Through Diversity. A Festschrift for Ludwig von Bertalanffy. Gordon & Breach Science Pub

- ^ Bertalanffy, L. von, (1969). General System Theory. New York: George Braziller, pp. 39-40

- ^ Bertalanffy, L. von, (1969). General System Theory. New York: George Braziller, pp. 139-1540

- ^ Bertalanffy, L. von, (1969). General System Theory. New York: George Braziller, pp. 196

- ^ Bertalanffy, L. von, (1969). General System Theory. New York: George Braziller, pp. 194-197

External links

- International Society for the Systems Sciences' biography of Ludwig von Bertalanffy

- Bertalanffy Center for the Study of Systems Science BCSSS in Vienna.

- Ludwig von Bertalanffy (1901-1972): A Pioneer of General Systems Theory working paper by T.E. Weckowicz, University of Alberta Center for Systems Research.