Leverage (finance)

In finance, leverage (sometimes referred to as gearing in the United Kingdom) is a general term for any technique to multiply gains and losses.[1] Common ways to attain leverage are borrowing money, buying fixed assets and using derivatives.[2] Important examples are:

- A public corporation may leverage its equity by borrowing money. The more it borrows, the less equity capital it needs, so any profits or losses are shared among a smaller base and are proportionately larger as a result.[3]

- A business entity can leverage its revenue by buying fixed assets. This will increase the proportion of fixed, as opposed to variable, costs, meaning that a change in revenue will result in a larger change in operating income.[4][5]

- Hedge funds often leverage their assets by using derivatives. A fund might get any gains or losses on $20 million worth of crude oil by posting $1 million of cash as margin.[6]

Contents |

Measuring leverage

A good deal of confusion arises in discussions among people who use different definitions of leverage. The term is used differently in investments and corporate finance, and has multiple definitions in each field.[7]

Investments

Accounting leverage is total assets divided by total assets minus total liabilities.[8] Notional leverage is total notional amount of assets plus total national amount of liabilities divided by equity.[1] Economic leverage is volatility of equity divided by volatility of an unlevered investment in the same assets. To understand the differences, consider the following positions, all funded with $100 of cash equity.[9]

- Buy $100 of crude oil. Assets are $100 ($100 of oil), there are no liabilities. Accounting leverage is 1 to 1. Notional amount is $100 ($100 of oil), there are no liabilities and there is $100 of equity. Notional leverage is 1 to 1. The volatility of the equity is equal to the volatility of oil, since oil is the only asset and you own the same amount as your equity, so economic leverage is 1 to 1.

- Borrow $100 and buy $200 of crude oil. Assets are $200, liabilities are $100 so accounting leverage is 2 to 1. Notional amount is $200, equity is $100 so notional leverage is 2 to 1. The volatility of the position is twice the volatility of an unlevered position in the same assets, so economic leverage is 2 to 1.

- Buy $100 of crude oil, borrow $100 worth of gasoline and sell the gasoline for $100. You now have $100 cash, $100 of crude oil and owe $100 worth of gasoline. Your assets are $200, liabilities are $100 so accounting leverage is 2 to 1. You have $200 notional amount of assets plus $100 notional amount of liabilities, with $100 of equity, so your notional leverage is 3 to 1. The volatility of your position might be half the volatility of an unlevered investment in the same assets, since the price of oil and the price of gasoline are positively correlated, so your economic leverage might be 0.5 to 1.

- Buy $100 of a 10-year fixed-rate treasury bond, and enter into a fixed-for-floating 10-year interest rate swap to convert the payments to floating rate. The derivative is off-balance sheet, so it is ignored for accounting leverage. Accounting leverage is therefore 1 to 1. The notional amount of the swap does count for notional leverage, so notional leverage is 2 to 1. The swap removes most of the economic risk of the treasury bond, so economic leverage is near zero.

Corporate finance

Degree of Operating Leverage (DOL)= (EBIT + Fixed costs) / EBIT; Degree of Financial Leverage (DFL)= EBIT / ( EBIT - Total Interest expense ); Degree of Combined Leverage (DCL)= DOL * DFL

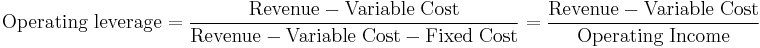

Accounting leverage has the same definition as in investments.[10] There are several ways to define operating leverage, the most common.[11] is:

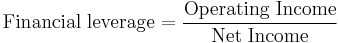

Financial leverage is usually defined[8] as:

Operating leverage is an attempt to estimate the percentage change in operating income (earnings before interest and taxes or EBIT) for a one percent change in revenue.[8]

Financial leverage tries to estimate the percentage change in net income for a one percent change in operating income.[12][13]

The product of the two is called Total leverage,[14] and estimates the percentage change in net income for a one percent change in revenue.[15]

There are several variants of each of these definitions,[16] and the financial statements are usually adjusted before the values are computed.[8] Moreover, there are industry-specific conventions that differ somewhat from the treatment above.[17]

Leverage and ROE

If we have to check real effect of leverage on ROE, we have to study financial leverage. Financial leverage refers to the use of debt to acquire additional assets. Financial leverage may decrease or increase return on equity in different conditions. Financial over-leveraging means incurring a huge debt by borrowing funds at a lower rate of interest and using the excess funds in high risk investments in order to maximize returns.[18]

Leverage and risk

The most obvious risk of leverage is that it multiplies losses. A corporation that borrows too much money might face bankruptcy during a business downturn, while a less-levered corporation might survive. An investor who buys a stock on 50% margin will lose 40% of his money if the stock declines 20%.[9]

There is an important implicit assumption in that account, however, which is that the underlying levered asset is the same as the unlevered one. If a company borrows money to modernize, or add to its product line, or expand internationally, the additional diversification might more than offset the additional risk from leverage.[9] Or if an investor uses a fraction of his or her portfolio to margin stock index futures and puts the rest in a money market fund, he or she might have the same volatility and expected return as an investor in an unlevered equity index fund, with a limited downside.[6] So while adding leverage to a given asset always adds risk, it is not the case that a levered company or investment is always riskier than an unlevered one. In fact, many highly-levered hedge funds have less return volatility than unlevered bond funds,[6] and public utilities with lots of debt are usually less risky stocks than unlevered technology companies.[9]

Popular risks

There is a popular prejudice against leverage rooted in the observation that people who borrow a lot of money often end up badly. But the issue here is those people are not leveraging anything, they're borrowing money for consumption.[9]

In finance, the general practice is to borrow money to buy an asset with a higher return than the interest on the debt.[7] That at least might work out. People who consistently spend more than they make have a problem, but it's overspending (or underearning), not leverage. The same point is more controversial for governments.

People sometimes borrow money out of desperation rather than calculation. That also is not leverage.[9] But it is true that leverage sometimes increases involuntarily. When Long-Term Capital Management collapsed with over 100 to 1 leverage, it wasn't that the principals tried to run the firm at 100 to 1 leverage, it was that as equity eroded and they were unable to liquidate positions, the leverage level was beyond their control. One hundred to one leverage was a symptom of their problems, not the cause (although, of course, part of the cause was the 27 to 1 leverage the firm was running before it got into trouble, and the 55 to 1 leverage it had been forced up to by mid-August 1998 before the real troubles started).[9] But the point is the fact that collapsing entities often have a lot of leverage does not mean that leverage causes collapses.

Involuntary leverage is a risk.[7] It means that as things get bad, leverage goes up, multiplying losses as things continue to go down. This can lead to rapid ruin, even if the underlying asset value decline is mild or temporary.[9] The risk can be mitigated by negotiating the terms of leverage, and by leveraging only liquid assets.[6]

Forced position reductions

A common misconception is that levered entities are forced to reduce positions as they lose money. This is only true if the entity is run at maximum leverage.[1] For example, if a person has $100, borrows another $100 and buys $200 worth of oil, he has 2 to 1 accounting leverage. If the price of oil declines 25%, he has $50 of equity supporting $150 worth of oil, 3 to 1 accounting leverage. If 2 to 1 is the maximum his counterparties will allow him, he has to sell one-third of his position to pay his debt down to $50. Now if oil goes back up to the original price, he has only $83 of equity. He lost 17 percent of his equity, even though the price of oil ended up back at its original price. Now if the price of oil declines 25%, the investor has to put up an additional $50 of margin, but he still has $40 of unencumbered cash. He may or may not wish to reduce the position, but he is not forced to do so. The point is that it is using maximum leverage that can force position reductions, not simply using leverage.[6] It often surprises people to learn that hedge funds running at 10 to 1 or higher notional leverage ratios hold 80 percent or 90 percent cash.

Model risk

Another risk of leverage is model risk. Many investors run high levels of notional leverage but low levels of economic leverage (in fact, these are the type of strategies hedge funds are named for, although not all hedge fund pursue them). Economic leverage depends on model assumptions.[6] For example, a fund with $100 might feel comfortable holding $1,000 long positions in crude oil futures and $1,000 of short positions in gasoline futures. The notional leverage is 20 to 1 (accounting leverage is zero) but the fund might estimate economic leverage is only 1 to 1, that is the fund may assume a 10% fall in the price of oil will cause a 9% fall in the price of gasoline, so the fund will lose only 10% net ($100 loss on the oil long and $90 profit on the gasoline short). If that assumption is incorrect, the fund may have much more economic leverage than it thinks. For example, if refinery capacity is shut down by a hurricane, the price of oil may fall (less demand from refineries) while the price of gasoline might rise (less supply from refineries). A 5% fall in the price of oil and a 5% rise in the price of gasoline could wipe out the fund.[9]

Counterparty risk

Leverage may involve a counterparty, either a creditor or a derivative counterparty. It doesn't always do that, for example a company levering by acquiring a fixed asset has no further reliance on a counterparty.[2] In the case of a creditor, most of the risk is usually on the creditor's side, but there can be risks to the borrower, such as demand repayment clauses or rights to seize collateral.[9] If a derivative counterparty fails, unrealized gains on the contract may be jeopardized. These risks can be mitigated by negotiating terms, including mark-to-market collateral.[6]

Worked Example

[19] Calculate equity return given:

5% Projected Return on Investment

4% Cost of Debt

8:1 Leverage Debt:Equity

LONG-FORM MATH

Investment (8+1) * 5% = 45

less Interest (8) * 4% = 32

equals Equity 1 * 13%= 13

SHORT-FORM GENERIC CALCULATION

Interest Rate Differential (5-4) = 1%

Debt to Equity Multiple (8/1) = 8

Multiply Line1 * Line2 (1*8) = 8%

Add Investment Return + 5%

Equals Total Return (8+5) = 13%

Leverage and bank regulation

Prior to the 1980s, quantitative limits on bank leverage were rare. Banks in most countries had a reserve requirement, a fraction of deposits that was required to be held in liquid form, generally precious metals or government notes or deposits. This does not limit leverage. A capital requirement is a fraction of assets that is required to be held in the form of equity or equity-like securities. Although these two are often confused, they are in fact opposite. A reserve requirement is a fraction of certain liabilities (from the right hand side of the balance sheet) that must be held as a certain kind of asset (from the left hand side of the balance sheet). A capital requirement is a fraction of assets (from the left hand side of the balance sheet) that must be held as a certain kind of liability or equity (from the right hand side of the balance sheet). Before the 1980s, regulators typically imposed judgmental capital requirements, a bank was supposed to be "adequately capitalized," but not objective rules.[20]

National regulators began imposing formal capital requirements in the 1980s, and by 1988 most large multinational banks were held to the Basel I standard. Basel I categorized assets into five risk buckets, and mandated minimum capital requirements for each. This limits accounting leverage. If a bank is required to hold 8% capital against an asset, that is the same as an accounting leverage limit of 1/.08 or 12.5 to 1.[21]

While Basel I is generally credited with improving bank risk management it suffered from two main defects. It did not require capital for off-balance sheet risks (there was a clumsy provisions for derivatives, but not for other off-balance sheet exposures) and it encouraged banks to pick the riskiest assets in each bucket (for example, the capital requirement was the same for all corporate loans, whether to solid companies or ones near bankruptcy, and the requirement for government loans was zero).[20]

Work on Basel II began in the early 1990s and it was implemented in stages beginning in 2005. Basel II attempted to limit economic leverage rather than accounting leverage. It required advanced banks to estimate the risk of their positions and allocate capital accordingly. While this is much more rational in theory, it is more subject to estimation error, both honest and opportunitistic.[21] The poor performance of many banks in during the financial crisis of 2007-2009 led to calls to reimpose leverage limits, by which most people meant accounting leverage limits, if they understood the distinction at all. However, in view of the problems with Basel I, it seems likely that the some hybrid of accounting and notional leverage will be used, and the leverage limits will be imposed in addition to, not instead of, Basel II economic leverage limits.[22]

Leverage and the financial crisis of 2007–2009

The financial crisis of 2007–2009, like many previous financial crises, was blamed in part on "excessive leverage." However, the word is used in several different senses.

- Consumers in the United States and many other developed countries borrowed large amounts of money, $2.6 trillion in the United States alone.[23] For most of this, "leverage" is a euphemism as the borrowing was used to support consumption rather than to lever anything.[24] Only people who borrowed for investment, such as speculative house purchases or buying stocks, were using leverage in the financial sense.

- Financial institutions were highly levered. Lehman Brothers, for example, in its last annual financial statements, showed accounting leverage of 30.7 times ($691 billion in assets divided by $22 billion in stockholders’ equity).[25] Bankruptcy examiner Anton R. Valukas determined that the true accounting leverage was higher, it had been understated due to dubious accounting treatments including the so-called repo 105 (Allowed by Ernst & Young).[26] Accounting leverage is the ratio usually cited by the press.

- Notional leverage more than twice as high, due to off-balance sheet transactions. At the end of 2007, Lehman had $738 billion of notional derivatives in addition to the assets above, plus significant off-balance sheet exposures to special purpose entities, structured investment vehicles and conduits, plus various lending commitments, contractual payments and contingent obligations.[25]

- On the other hand, almost half of Lehman’s balance sheet consisted of closely offsetting positions and very low risk assets, such as regulatory deposits. The company emphasized "net leverage", which excluded these assets. On that basis, Lehman held $373 billion of "net assets" and a "net leverage ratio" of 16.1.[25] This is not a standardized computation, but it probably corresponds more closely to what most people think of when they hear a leverage ratio.

See also

Use of Language

Levering has come to be known as Leveraging, in financial communities. This may have originally been a slang adaptation, since leverage was a noun, however, modern dictionaries (such as Random House Dictionary and Merriam-Webster's Dictionary of Law) refer to its use as a verb as well.[27] It was first adopted for use as a verb in American English in 1957.[28]

References

- ^ a b c Brigham, Eugene F., Fundamentals of Financial Management (1995).

- ^ a b Mock, E. J., R. E. Schultz, R. G. Schultz, and D. H. Shuckett, Basic Financial Management (1968).

- ^ Grunewald, Adolph E. and Erwin E. Nemmers, Basic Managerial Finance (1970).

- ^ Ghosh, Dilip K. and Robert G. Sherman, "Leverage, Resource Allocation and Growth," Journal of Business Finance & Accounting (June 1993), p. 575-582.

- ^ Lang, Larry, Eli Ofek, and Rene M. Stulz, "Leverage, Investment, and Firm Growth," Journal of Financial Economics (January 1996), p. 3-29.

- ^ a b c d e f g Chew, Lillian, Managing Derivative Risks: The Use and Abuse of Leverage, John Wiley & Sons (July 1996).

- ^ a b c Van Horne, Financial Management and Policy (1971).

- ^ a b c d Weston, J. Fred and Eugene F. Brigham, Managerial Finance (1969).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Bodie, Zvi, Alex Kane and Alan J. Marcus, Investments, McGraw-Hill/Irwin (June 18, 2008)

- ^ Weston, J. Fred and Eugene F. Brigham, Managerial Finance (2010).

- ^ Brigham, Eugene F., Fundamentals of Financial Management (1995)

- ^ Blazenko, George W., "Corporate Leverage and the Distribution of Equity Returns," Journal of Business & Accounting (October 1996), p. 1097-1120).

- ^ Block, Stanley B. and Geoffrey A. Hirt, Foundations of Financial Management (1997).

- ^ Li, Rong-Jen and Glenn V. Henderson, Jr., "Combined Leverage and Stock Risk," Quarterly Journal of Business & Finance (Winter 1991), p. 18-39.

- ^ Huffman, Stephen P., "The Impact of Degrees of Operating and Financial Leverage on the Systematic Risk of Common Stock: Another Look," Quarterly Journal of Business & Economics (Winter 1989), p. 83-100.

- ^ Dugan, Michael T., Donald Minyard, and Keith A. Shriver, "A Re-examination of the Operating Leverage-Financial Leverage Tradeoff," Quarterly Review of Economics & Finance (Fall 1994), p. 327-334.

- ^ Darrat, Ali F. and Tarun K. Mukherjee, "Inter-Industry Differences and the Impact of Operating and Financial Leverages on Equity Risk," Review of Financial Economics (Spring 1995), p. 141-155.

- ^ Leverage Effect on ROE

- ^ Math for calculating leverage effects

- ^ a b Ong, Michael K., The Basel Handbook: A Guide for Financial Practitioners, Risk Books (December 2003)

- ^ a b Saita, Francesco, Value at Risk and Bank Capital Management: Risk Adjusted Performances, Capital Management and Capital Allocation Decision Making, Academic Press (February 3, 2007)

- ^ Tarullo, Daniel K., Banking on Basel: The Future of International Financial Regulation, Peterson Institute for International Economics (September 30, 2008)

- ^ Federal Reserve Statistical Release G19 Consumer Credit.

- ^ Bureau of Economic Analysis: National Income and Products Account Table 2.1.

- ^ a b c Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc Annual Report for year ended November 30, 2007.

- ^ Report of Anton R. Valukas, Examiner, to the United States Bankruptcy Court, Southern District of New York, Chapter 11 Case No. 08-13555 (JMP).

- ^ ["leverage." Merriam-Webster's Dictionary of Law. Merriam-Webster, Inc. 07 Jun. 2011. <[Dictionary.com http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/leverage>]

- ^ "leverage." Online Etymology Dictionary. Douglas Harper, Historian. 07 Jun. 2011. [<Dictionary.com http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/leverage>.]

[[Id:Bahasa Indonesia