Lenstra elliptic curve factorization

The Lenstra elliptic curve factorization or the elliptic curve factorization method (ECM) is a fast, sub-exponential running time algorithm for integer factorization which employs elliptic curves. For general purpose factoring, ECM is the third-fastest known factoring method. The second fastest is the multiple polynomial quadratic sieve and the fastest is the general number field sieve. The Lenstra elliptic curve factorization is named after Hendrik Lenstra.

Practically speaking, ECM is considered a special purpose factoring algorithm as it is most suitable for finding small factors. Currently[update], it is still the best algorithm for divisors not greatly exceeding 20 to 25 digits (64 to 83 bits or so), as its running time is dominated by the size of the smallest factor p rather than by the size of the number n to be factored. Frequently, ECM is used to remove small factors from a very large integer with many factors; if the remaining integer is still composite, then it has only large factors and is factored using general purpose techniques. The largest factor found using ECM so far has 73 digits and was discovered on 6 March 2010 by Joppe Bos, Thorsten Kleinjung, Arjen Lenstra and Peter Montgomery.[1] Increasing the number of curves tested improves the chances of finding a factor, but they are not linear with the increase in the number of digits.

Contents |

Lenstra's elliptic curve factorization

The Lenstra elliptic curve factorization method to find a factor of the given number n works as follows:

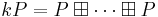

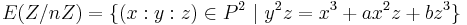

- Pick a random elliptic curve over

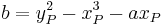

, given by an equation of the form y2 = x3 + ax + b (mod n), and a non-trivial point P on it. Say, pick first a point P=(x,y) with random non-zero coordinates x,y (mod n), then pick a random non-zero a (mod n), then take b = y2 - x3 - ax (mod n).

, given by an equation of the form y2 = x3 + ax + b (mod n), and a non-trivial point P on it. Say, pick first a point P=(x,y) with random non-zero coordinates x,y (mod n), then pick a random non-zero a (mod n), then take b = y2 - x3 - ax (mod n). - We will compute certain multiples

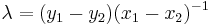

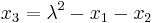

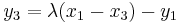

(k times) of the point P using the standard addition rule

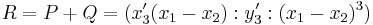

(k times) of the point P using the standard addition rule  on our elliptic curve: given two points P,Q on the curve, their sum

on our elliptic curve: given two points P,Q on the curve, their sum  can be computed using the formulas given in the group law section of the article on elliptic curves. These formulas contain the "slope" of the line connecting P and Q, hence involve divisions between residue classes modulo n, which can be performed using the extended Euclidean algorithm. In particular, division by some v (mod n) includes the calculation of the greatest common divisor gcd(v,n).

can be computed using the formulas given in the group law section of the article on elliptic curves. These formulas contain the "slope" of the line connecting P and Q, hence involve divisions between residue classes modulo n, which can be performed using the extended Euclidean algorithm. In particular, division by some v (mod n) includes the calculation of the greatest common divisor gcd(v,n).

- If the slope is of the form u/v with gcd(u,n)=1, then v=0 (mod n) means that the result of the

-addition will be

-addition will be  , the point at infinity on the curve. However, if gcd(v,n) is neither 1 nor n, then the

, the point at infinity on the curve. However, if gcd(v,n) is neither 1 nor n, then the  -addition will not produce a meaningful point on the curve, which shows that our elliptic curve is not a group (mod n), but, more importantly for now, gcd(v,n) is a non-trivial factor of n.

-addition will not produce a meaningful point on the curve, which shows that our elliptic curve is not a group (mod n), but, more importantly for now, gcd(v,n) is a non-trivial factor of n.

- If the slope is of the form u/v with gcd(u,n)=1, then v=0 (mod n) means that the result of the

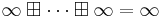

- Compute eP on the elliptic curve (mod n), where e is product of many small numbers: say, a product of small primes raised to small powers, as in the p − 1 algorithm, or the factorial B! for some not too large B. This can be done efficiently, one small factor at a time. Say, to get B!P, first compute 2P, then 3(2P), then 4(3!P), and so on. Of course, B should be small enough so that B-wise

-addition can be performed in reasonable time.

-addition can be performed in reasonable time. -

- If we were able to finish all the calculations above without encountering non-invertible elements (mod n), then we need to try again with some other curve and starting point.

- If we found

at some stage (the point at infinity on the elliptic curve), then again we should start over with a new curve and starting point, since

at some stage (the point at infinity on the elliptic curve), then again we should start over with a new curve and starting point, since  is the zero element for

is the zero element for  , so after this point we would be just repeating

, so after this point we would be just repeating  .

. - If we encountered a gcd(v,n) at some stage that was neither 1 nor n, then we are done: it is a non-trivial factor of n.

The time complexity depends on the size of the factor and can be represented by O(e(√2 + o(1)) √(ln p ln ln p)), where p is the smallest factor of n.

Why does the algorithm work?

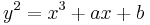

If p and q are two prime divisors of n, then y2 = x3 + ax + b (mod n) implies the same equation also (mod p) and (mod q). These two smaller elliptic curves with the  -addition are now genuine groups. If these groups have Np and Nq elements, respectively, then for any point P on the original curve, by Lagrange's theorem,

-addition are now genuine groups. If these groups have Np and Nq elements, respectively, then for any point P on the original curve, by Lagrange's theorem,  on the curve (mod p) implies that k divides Np; moreover,

on the curve (mod p) implies that k divides Np; moreover,  . The analogous statement holds for q. When the elliptic curve is chosen randomly, then Np and Nq are random numbers close to p+1 and q+1, respectively (see below). Hence it is unlikely that most of the prime factors of Np and Nq are the same, and it is quite likely that while computing eP, we will encounter some kP that is

. The analogous statement holds for q. When the elliptic curve is chosen randomly, then Np and Nq are random numbers close to p+1 and q+1, respectively (see below). Hence it is unlikely that most of the prime factors of Np and Nq are the same, and it is quite likely that while computing eP, we will encounter some kP that is  (mod p) but not (mod q), or vice versa. When this is the case, kP does not exist on the original curve, and in the computations we found some v with either gcd(v,p)=p or gcd(v,q)=q, but not both. That is, gcd(v,n) gave a non-trivial factor of n.

(mod p) but not (mod q), or vice versa. When this is the case, kP does not exist on the original curve, and in the computations we found some v with either gcd(v,p)=p or gcd(v,q)=q, but not both. That is, gcd(v,n) gave a non-trivial factor of n.

ECM is at its core an improvement of the older p − 1 algorithm. The p − 1 algorithm finds prime factors p such that p − 1 is b-powersmooth for small values of b. For any e, a multiple of p − 1, and any a relatively prime to p, by Fermat's little theorem we have ae ≡ 1 (mod p). Then gcd(ae − 1, n) is likely to produce a factor of n. However, the algorithm fails when p-1 has large prime factors, as is the case for numbers containing strong primes, for example.

ECM gets around this obstacle by considering the group of a random elliptic curve over the finite field Zp, rather than considering the multiplicative group of Zp which always has order p − 1.

The order of the group of an elliptic curve over Zp varies (quite randomly) between p + 1 − 2√p and p + 1 + 2√p by Hasse's theorem, and is likely to be smooth for some elliptic curves. Although there is no proof that a smooth group order will be found in the Hasse-interval, by using heuristic probabilistic methods, the Canfield-Erdős-Pomerance theorem with suitably optimized parameter choices, and the L-notation, we can expect to try L[√2 / 2, √2] curves before getting a smooth group order. This heuristic estimate is very reliable in practice.

An example

The following example is from Trappe & Washington (2006), with some details added.

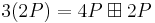

We want to factor n=455839. Let's choose the elliptic curve y2 = x3 + 5x - 5, with the point P=(1,1) on it, and let's try to compute (10!)P.

First we compute 2P. The slope of the tangent line at P is s=(3x2+5)/(2y)=4, and then the coordinates of 2P=(x′,y′) are x′=s2-2x=14 and y′=s(x-x′)-y=4(1-14)-1=-53, all numbers understood (mod n). Just to check that this 2P is indeed on the curve: (-53)2=2809=143+5·14-5.

Then we compute 3(2P). The slope of the tangent line at 2P is s=(3·142+5)/(2(-53))=-593/106 (mod n). Using the Euclidean algorithm: 455839=4300·106+39, then 106=2·39+28, then 39=28+11, then 28=2·11+6, then 11=6+5, then 6=5+1. Hence gcd(455839,106)=1, and working backwards (a version of the extended Euclidean algorithm): 1=6-5=2·6-11=2·28-5·11=7·28-5·39=7·106-19·39=81707·106-19·455839. Hence 106-1=81707 (mod 455839), and -593/106=133317 (mod 455839). Given this s, we can compute the coordinates of 2(2P), just as we did above: 4P=(259851,116255). Just to check that this is indeed a point on the curve: y2=54514=x3+5x-5 (mod 455839). After this, we can compute  .

.

We can similarly compute 4!P, and so on, but 8!P requires inverting 599 (mod 455839). The Euclidean algorithm gives that 455839 is divisible by 599, and we have found a factorization 455839=599·761.

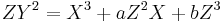

The reason that this worked is that the curve (mod 599) has 640=27·5 points, while (mod 761) it has 777=3·7·37 points. Moreover, 640 and 777 are the smallest positive integers k such that  on the curve (mod 599) and (mod 761), respectively. Since 8! is a multiple of 640 but not a multiple of 777, we have

on the curve (mod 599) and (mod 761), respectively. Since 8! is a multiple of 640 but not a multiple of 777, we have  on the curve (mod 599), but not on the curve (mod 761), hence the repeated addition broke down here, yielding the factorization.

on the curve (mod 599), but not on the curve (mod 761), hence the repeated addition broke down here, yielding the factorization.

The algorithm with projective coordinates

Before we consider the projective plane over  /~, first have a look at the 'normal' projective space over

/~, first have a look at the 'normal' projective space over  . Now, instead of studying the points, the lines through the origin will be studied. The line can be represented a non-zero point

. Now, instead of studying the points, the lines through the origin will be studied. The line can be represented a non-zero point  if you use the equivalence relation ~ on it, given by:

if you use the equivalence relation ~ on it, given by:  if and only if there exists a non-zero number

if and only if there exists a non-zero number  such that

such that  ,

,  and

and  . Due to this equivalence relation the space will be called a plane. In the projective plane, points, denoted by

. Due to this equivalence relation the space will be called a plane. In the projective plane, points, denoted by  , are 'the same' as lines in a threedimensional space that go through the origin. Remark that the point

, are 'the same' as lines in a threedimensional space that go through the origin. Remark that the point  does not exist here, because these does not represent a line. Now we observe that almost all lines go to the

does not exist here, because these does not represent a line. Now we observe that almost all lines go to the  -plane, except from the lines parallel to this plane. This lines are in the projective plane the 'points of infinity' that are used in the affine

-plane, except from the lines parallel to this plane. This lines are in the projective plane the 'points of infinity' that are used in the affine  -plane above.

-plane above.

In the algorithm only the group structure of an elliptic curve over the field  is used. Therefore we not necessarily need the field

is used. Therefore we not necessarily need the field  . A finite field will also provide a group structure on the elliptic curve. However, considering the same curve and operation over

. A finite field will also provide a group structure on the elliptic curve. However, considering the same curve and operation over  /~ with

/~ with  not a prime does not give a group. The Elliptic Curve Method makes use of the failure cases of the addition law.

not a prime does not give a group. The Elliptic Curve Method makes use of the failure cases of the addition law.

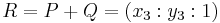

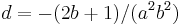

We now state the algorithm in projective coordinates. The neutral element is then given by the point in infinity  . Let

. Let  be a (positive) integer and consider the elliptic curve (a set of points with some structure on it)

be a (positive) integer and consider the elliptic curve (a set of points with some structure on it)  .

.

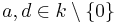

- Pick

in

in  and let

and let  be unequal to zero.

be unequal to zero. - Calculate

. The elliptic curve

. The elliptic curve  is then in Weierstrass form given by

is then in Weierstrass form given by  and by using projective coordinates the elliptic curve is given by the homogenous equation

and by using projective coordinates the elliptic curve is given by the homogenous equation  . It has the point

. It has the point  .

. - Choose an upperbound

for this elliptic curve. Remark: You will only find factors

for this elliptic curve. Remark: You will only find factors  if the group order of the elliptic curve

if the group order of the elliptic curve  over

over  (denoted by #

(denoted by # ) is B-smooth, which means that all prime factors of #

) is B-smooth, which means that all prime factors of # have to be less or equal to

have to be less or equal to  .

. - Calculate

.

. - Calculate

(k times) in the ring

(k times) in the ring  . Note that if #

. Note that if # is

is  -smooth and

-smooth and  is prime (and therefore

is prime (and therefore  is a field) that

is a field) that  . However, if only #

. However, if only # is B-smooth for some divisor

is B-smooth for some divisor  of

of  , the product might not be (0:1:0) because addition and multiplication are not well-defined if

, the product might not be (0:1:0) because addition and multiplication are not well-defined if  is not prime. In this case, a non-trivial divisor can be found!

is not prime. In this case, a non-trivial divisor can be found! - If not, then go back to step 2. If this does occur, then you will notice this when simplifying the product

.

.

In point 5 it is said that under the right circumstances a non-trivial divisor can be found. As pointed out in Lenstra's article (Factoring Integers with Elliptic Curves) the addition needs the assumption  . If

. If  are not

are not  and distinct (otherwise addition works similar, but a little different), then addition works as follows:

and distinct (otherwise addition works similar, but a little different), then addition works as follows:

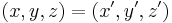

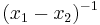

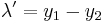

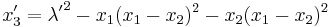

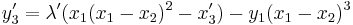

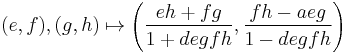

- To calculate:

,

,  ,

,  ,

, ,

, ,

, .

.

If addition fails, this will be due calculating  fails. In particular, because

fails. In particular, because  can not always be calculated if

can not always be calculated if  is not prime (and therefore

is not prime (and therefore  is not a field). Without making use of

is not a field). Without making use of  being a field, one could calculate:

being a field, one could calculate:

,

, ,

, ,

, , and simplify if possible.

, and simplify if possible.

This calculation is always legal and if the gcd of the  -coordinate with

-coordinate with  is unequal to 1 or

is unequal to 1 or  , so when simplifying fails, then a non-trivial divisor of

, so when simplifying fails, then a non-trivial divisor of  is found.

is found.

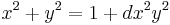

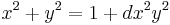

Twisted Edwards curves

The use of Edwards curves needs fewer modular multiplications and less time then the use of Montgomery curves or Weierstrass curves (other used methods). Using Edwards curves you can also find more primes.

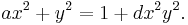

Definition: Let  be a field in which

be a field in which  , and let

, and let  with

with  . Then the twisted Edwards curve

. Then the twisted Edwards curve  is given by

is given by  An Edwards curve is a twisted Edwards curve in which

An Edwards curve is a twisted Edwards curve in which  .

.

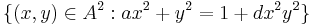

There are five known ways to build a set of point on an Edwards curve: the set of affine points, the set of projective points, the set of inverted points, the set of extended points and the set of completed points.

The set of affine points is given by:  .

.

The addition law is given by  . The point (0,1) is its neutral element and the negative of

. The point (0,1) is its neutral element and the negative of  is

is  . The other representations are defined similar to how the projective Weierstrass curve follows from the affine.

. The other representations are defined similar to how the projective Weierstrass curve follows from the affine.

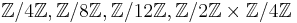

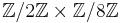

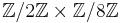

Any elliptic curve in Edwards form has a point of order 4. So the torsion group of an Edwards curve over  is isomorphic to either

is isomorphic to either  or

or  .

.

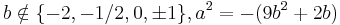

The most interesting cases for ECM are  and

and  , since they force the group orders of the curve modulo primes to be divisible by 12 and 16 respectively. The following curves have a torsion group isomorphic to

, since they force the group orders of the curve modulo primes to be divisible by 12 and 16 respectively. The following curves have a torsion group isomorphic to  :

:

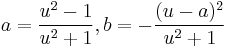

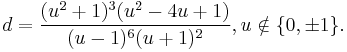

with point

with point  where

where  and

and

with point

with point  where

where  and

and

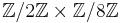

Every Edwards curve with a point of order 3 can be written in the ways shown above. Curves with torsion group isomorphic to  and

and  can be found on http://eprint.iacr.org/2008/016 page 30-32.

can be found on http://eprint.iacr.org/2008/016 page 30-32.

Stage 2

The above text is about the first stage of elliptic curve factorisation. There one hopes to find a prime divisor  such that

such that  is the neutral element of

is the neutral element of  . In the second stage one hopes to have found a prime divisor

. In the second stage one hopes to have found a prime divisor  such that

such that  has small prime order in

has small prime order in  .

.

We hope the order to be between  and

and  , where

, where  is determined in stage 1 and

is determined in stage 1 and  is new stage 2 parameter. Checking for a small order of

is new stage 2 parameter. Checking for a small order of  , can be done by computing

, can be done by computing  modulo

modulo  for each prime

for each prime  .

.

Success probability using EECM-MPFQ

For speedup techniques using Edward curves and implementation results, see: http://eprint.iacr.org/2008/016 page 30-32.

Hyperelliptic Curve Method (HECM)

There are recent developments in using hyperelliptic curves to factor integers. Cosset shows in his article (of 2010) that one can build a hyperelliptic curve with genus two (so a curve  with

with  of degree 5) which gives the same result as using two 'normal' elliptic curves at the same time. By making use of the Kummer Surface calculation is more efficient. The disadvantages of the hyperelliptic curve (versus an elliptic curve) are compensated by this alternative way of calculating. Therefore Cosset roughly claims that using hyperelliptic curves for factorization is no worse than using elliptic curves.

of degree 5) which gives the same result as using two 'normal' elliptic curves at the same time. By making use of the Kummer Surface calculation is more efficient. The disadvantages of the hyperelliptic curve (versus an elliptic curve) are compensated by this alternative way of calculating. Therefore Cosset roughly claims that using hyperelliptic curves for factorization is no worse than using elliptic curves.

See also

- UBASIC for practical program (ECMX).

References

- Bernstein, D. J.; Birkner, P.; Lange, T.; Peters, C. (2008). "ECM using Edwards curves". ePrint archive 2008/016. http://eprint.iacr.org/2008/016.

- Bosma, W.; Hulst, M. P. M. van der (1990). Primality proving with cyclotomy. Ph.D. Thesis, Universiteit van Amsterdam. OCLC 256778332.

- Brent, Richard P. (1999). "Factorization of the tenth Fermat number". Mathematics of Computation 68 (225): 429–451. doi:10.1090/S0025-5718-99-00992-8.

- Cohen, Henri (1996). A Course in Computational Algebraic Number Theory. New York, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-55640-0.

- Cosset, R. (2010). "Factorization with genus 2 curves". Mathematics of Computation 79 (270): 1191–1208. doi:10.1090/S0025-5718-09-02295-9.

- Lenstra, A. K.; Lenstra Jr., H. W., eds (1993). The development of the number field sieve. Lecture Notes in Mathematics. 1554. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. MR96m:11116.

- Lenstra Jr., H. W. (1987). "Factoring integers with elliptic curves". Annals of Mathematics 126 (3): 649–673. JSTOR 1971363. MR89g:11125.

- Pomerance, Carl; Richard Crandall (2001). "Section 7.4: Elliptic curve method". Prime Numbers: A Computational Perspective (1st ed.). Springer. pp. 301–313. ISBN 0-387-94777-9.

- Pomerance, Carl (1985). "The quadratic sieve factoring algorithm". Advances in Cryptology, Proc. Eurocrypt '84. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 209. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. pp. 169–182. MR87d:11098.

- Pomerance, Carl (1996). "A Tale of Two Sieves" (PDF). Notices of the American Mathematical Society 43 (12): 1473–1485. http://www.ams.org/notices/199612/pomerance.pdf.

- Silverman, Robert D. (1987). "The Multiple Polynomial Quadratic Sieve". Mathematics of Computation 48 (177): 329–339. doi:10.1090/S0025-5718-1987-0866119-8.

- Trappe, W.; Washington, L. C. (2006). Introduction to Cryptography with Coding Theory (Second ed.). Pearson Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-186239-1.

- Watras, Marcin (2008). Cryptography, Number Analysis, and Very Large Numbers. Bydgoszcz: Wojciechowski-Steinhagen. PL:5324564.

External links

- Factorization using the Elliptic Curve Method, a Java applet which uses ECM and switches to the Self-Initializing Quadratic Sieve when it is faster.

- GMP-ECM, an efficient implementation of ECM.

- ECMNet, an easy client-server implementation that works with several factorization projects.

- pyecm, a python implementation of ECM. Much faster with psyco and/or gmpy.

- Distributed computing project yoyo@Home Subproject ECM is a program for Elliptic Curve Factorization which is used by a couple of projects to find factors for different kind of numbers.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||