Lamb waves

Lamb waves propagate in solid plates. They are elastic waves whose particle motion lies in the plane that contains the direction of wave propagation and the plate normal (the direction perpendicular to the plate). In 1917, the English mathematician Horace Lamb published his classic analysis and description of acoustic waves of this type. Their properties turned out to be quite complex. An infinite medium supports just two wave modes traveling at unique velocities; but plates support two infinite sets of Lamb wave modes, whose velocities depend on the relationship between wavelength and plate thickness.

Since the 1990s, the understanding and utilization of Lamb waves has advanced greatly, thanks to the rapid increase in the availability of computing power. Lamb's theoretical formulations have found substantial practical application, especially in the field of nondestructive testing.

The term Rayleigh–Lamb waves embraces the Rayleigh wave, a type of wave that propagates along a single surface. Both Rayleigh and Lamb waves are constrained by the elastic properties of the surface(s) that guide them.

Lamb's characteristic equations

In general, elastic waves in solid materials[1] are guided by the boundaries of the media in which they propagate. An approach to guided wave propagation, widely used in physical acoustics, is to seek sinusoidal solutions to the wave equation for linear elastic waves subject to boundary conditions representing the structural geometry. This is a classic eigenvalue problem.

Waves in plates were among the first guided waves to be analyzed in this way. The analysis was developed and published in 1917[2] by Horace Lamb, a leader in the mathematical physics of his day.

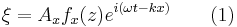

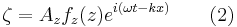

Lamb's equations were derived by setting up formalism for a solid plate having infinite extent in the x and y directions, and thickness d in the z direction. Sinusoidal solutions to the wave equation were postulated, having x- and z-displacements of the form

This form represents sinusoidal waves propagating in the x direction with wavelength 2π/k and frequency ω/2π. Displacement is a function of x, z, t only; there is no displacement in the y direction and no variation of any physical quantities in the y direction.

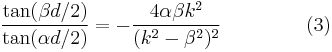

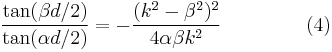

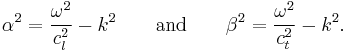

The physical boundary condition for the free surfaces of the plate is that the component of stress in the z direction at z = +/- d/2 is zero. Applying these two conditions to the above-formalized solutions to the wave equation, a pair of characteristic equations can be found. These are:

and

where

Inherent in these equations is a relationship between the angular frequency ω and the wave number k. Numerical methods are used to find the phase velocity cp = fλ = ω/k, and the group velocity cg = dω/dk, as functions of d/λ or fd. cl and ct are the longitudinal wave and shear wave velocities respectively.

The solution of these equations also reveals the precise form of the particle motion, which equations (1) and (2) represent in generic form only. It is found that equation (3) gives rise to a family of waves whose motion is symmetrical about the midplane of the plate (the plane z = 0), while equation (4) gives rise to a family of waves whose motion is antisymmetric about the midplane. Figure 1 illustrates a member of each family.

Lamb’s characteristic equations were established for waves propagating in an infinite plate - a homogeneous, isotropic solid bounded by two parallel planes beyond which no wave energy can propagate. In formulating his problem, Lamb confined the components of particle motion to the direction of the plate normal (z-direction) and the direction of wave propagation (x-direction). By definition, Lamb waves have no particle motion in the y-direction. Motion in the y-direction in plates is found in the so-called SH or shear-horizontal wave modes. These have no motion in the x- or z-directions, and are thus complementary to the Lamb wave modes. These two are the only wave types which can propagate with straight, infinite wave fronts in a plate as defined above.

Velocity dispersion inherent in the characteristic equations

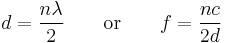

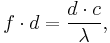

Lamb waves exhibit velocity dispersion; that is, their velocity of propagation c depends on the frequency (or wavelength), as well as on the elastic constants and density of the material. This phenomenon is central to the study and understanding of wave behavior in plates. Physically, the key parameter is the ratio of plate thickness d to wavelength  . This ratio determines the effective stiffness of the plate and hence the velocity of the wave. In technological applications, a more practical parameter readily derived from this is used, namely the product of thickness and frequency:

. This ratio determines the effective stiffness of the plate and hence the velocity of the wave. In technological applications, a more practical parameter readily derived from this is used, namely the product of thickness and frequency:

|

since for all waves |  |

The relationship between velocity and frequency (or wavelength) is inherent in the characteristic equations. In the case of the plate, these equations are not simple and their solution requires numerical methods. This was an intractable problem until the advent of the digital computer forty years after Lamb's original work. The publication of computer-generated "dispersion curves" by Viktorov[3] in the former Soviet Union, Firestone followed by Worlton in the United States, and eventually many others brought Lamb wave theory into the realm of practical applicability. Experimental waveforms observed in plates can be understood by interpretation with reference to the dispersion curves.

Dispersion curves - graphs that show relationships between wave velocity, wavelength and frequency in dispersive systems - can be presented in various forms. The form that gives the greatest insight into the underlying physics has  (angular frequency) on the y-axis and k (wave number) on the x-axis. The form used by Viktorov, that brought Lamb waves into practical use, has wave velocity on the y-axis and

(angular frequency) on the y-axis and k (wave number) on the x-axis. The form used by Viktorov, that brought Lamb waves into practical use, has wave velocity on the y-axis and  , the thickness/wavelength ratio, on the x-axis. The most practical form of all, for which credit is due to J. and H. Krautkrämer as well as to Floyd Firestone (who, incidentally, coined the phrase "Lamb waves") has wave velocity on the y-axis and fd, the frequency-thickness product, on the x-axis.

, the thickness/wavelength ratio, on the x-axis. The most practical form of all, for which credit is due to J. and H. Krautkrämer as well as to Floyd Firestone (who, incidentally, coined the phrase "Lamb waves") has wave velocity on the y-axis and fd, the frequency-thickness product, on the x-axis.

Lamb's characteristic equations indicate the existence of two entire families of sinusoidal wave modes in infinite plates of width  . This stands in contrast with the situation in unbounded media where there are just two wave modes, the longitudinal wave and the transverse or shear wave. As in Rayleigh waves which propagate along single free surfaces, the particle motion in Lamb waves is elliptical with its x and z components depending on the depth within the plate.[4] In one family of modes, the motion is symmetrical about the midthickness plane. In the other family it is antisymmetric. The phenomenon of velocity dispersion leads to a rich variety of experimentally observable waveforms when acoustic waves propagate in plates. It is the group velocity cg, not the above-mentioned phase velocity c or cp, that determines the modulations seen in the observed waveform. The appearance of the waveforms depends critically on the frequency range selected for observation. The flexural and extensional modes are relatively easy to recognize and this has been advocated as a technique of nondestructive testing.

. This stands in contrast with the situation in unbounded media where there are just two wave modes, the longitudinal wave and the transverse or shear wave. As in Rayleigh waves which propagate along single free surfaces, the particle motion in Lamb waves is elliptical with its x and z components depending on the depth within the plate.[4] In one family of modes, the motion is symmetrical about the midthickness plane. In the other family it is antisymmetric. The phenomenon of velocity dispersion leads to a rich variety of experimentally observable waveforms when acoustic waves propagate in plates. It is the group velocity cg, not the above-mentioned phase velocity c or cp, that determines the modulations seen in the observed waveform. The appearance of the waveforms depends critically on the frequency range selected for observation. The flexural and extensional modes are relatively easy to recognize and this has been advocated as a technique of nondestructive testing.

The zero-order modes

The symmetrical and antisymmetric zero-order modes deserve special attention. These modes have "nascent frequencies" of zero. Thus they are the only modes that exist over the entire frequency spectrum from zero to indefinitely high frequencies. In the low frequency range (i.e. when the wavelength is greater than the plate thickness) these modes are often called the “extensional mode” and the “flexural mode" respectively, terms that describe the nature of the motion and the elastic stiffnesses that govern the velocities of propagation. The elliptical particle motion is mainly in the plane of the plate for the symmetrical, extensional mode and perpendicular to the plane of the plate for the antisymmetric, flexural mode. These characteristics change at higher frequencies.

These two modes are the most important because (a) they exist at all frequencies and (b) in most practical situations they carry more energy than the higher-order modes.

The zero-order symmetrical mode (designated s0) travels at the "plate velocity" in the low-frequency regime where it is properly called the "extensional mode". In this regime the plate stretches in the direction of propagation and contracts correspondingly in the thickness direction. As the frequency increases and the wavelength becomes comparable with the plate thickness, curving of the plate starts to have a significant influence on its effective stiffness. The phase velocity drops smoothly while the group velocity drops somewhat precipitously towards a minimum. At higher frequencies yet, both the phase velocity and the group velocity converge towards the Rayleigh wave velocity - the phase velocity from above, and the group velocity from below.

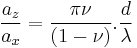

In the low-frequency limit for the extensional mode, the z- and x-components of the surface displacement are in quadrature and the ratio of their amplitudes is given by:

|

where  is Poisson's ratio.

is Poisson's ratio.

The zero-order antisymmetric mode (designated a0) is highly dispersive in the low frequency regime where it is properly called the "flexural mode". For very low frequencies (very thin plates) the phase and group velocities are both proportional to the square root of the frequency; the group velocity is twice the phase velocity. This simple relationship is a consequence of the stiffness/thickness relationship for thin plates in bending. At higher frequencies where the wavelength is no longer much greater than the plate thickness, these relationships break down. The phase velocity rises less and less quickly and converges towards the Rayleigh wave velocity in the high frequency limit. The group velocity passes through a maximum, a little faster than the shear wave velocity, when the wavelength is approximately equal to the plate thickness. It then converges, from above, to the Rayleigh wave velocity in the high frequency limit.

In experiments that allow both extensional and flexural modes to be excited and detected, the extensional mode often appears as a higher-velocity, lower-amplitude precursor to the flexural mode. The flexural mode is the more easily excited of the two, and often carries most of the energy.

The higher-order modes

As the frequency is raised, the higher-order wave modes make their appearance in addition to the zero-order modes. Each higher-order mode is “born” at a resonant frequency of the plate, and exists only above that frequency. For example, in a ¾ inch (19mm) thick steel plate at a frequency of 200 kHz, the first four Lamb wave modes are present and at 300 kHz, the first six. The first few higher-order modes can be distinctly observed under favorable experimental conditions. Under less than favorable conditions they overlap and can not be distinguished.

The higher-order Lamb modes are characterized by nodal planes within the plate, parallel to the plate surfaces. Each of these modes exists only above a certain frequency which can be called its "nascent frequency". There is no upper frequency limit for any of the modes. The nascent frequencies can be pictured as the resonant frequencies for longitudinal or shear waves propagating perpendicular to the plane of the plate, i.e.

where n is any positive integer. Here c can be either the longitudinal wave velocity or the shear wave velocity, and for each resulting set of resonances the corresponding Lamb wave modes are alternately symmetrical and antisymmetric. The interplay of these two sets results in a pattern of nascent frequencies that at first glance seems irregular. For example, in a 3/4 inch (19mm) thick steel plate having longitudinal and shear velocities of 5890 m/s and 3260 m/s respectively, the nascent frequencies of the antisymmetric modes a1, a2 and a3 are 86 kHz, 257 kHz and 310 kHz respectively, while the nascent frequencies of the symmetric modes s1, s2 and s3 are 155 kHz, 172 kHz and 343 kHz respectively.

At its nascent frequency, each of these modes has an infinite phase velocity and a group velocity of zero. In the high frequency limit, the phase and group velocities of all these modes converge to the shear wave velocity. Because of these convergences, the Rayleigh and shear velocities (which are very close to one another) are of major importance in thick plates. Simply stated in terms of the material of greatest engineering significance, most of the high-frequency wave energy that propagates long distances in steel plates is traveling at 3000–3300 m/s.

Particle motion in the Lamb wave modes is in general elliptical, having components both perpendicular to and parallel to the plane of the plate. These components are in quadrature, i.e. they have a 90° phase difference. The relative magnitude of the components is a function of frequency. For certain frequencies-thickness products, the amplitude of one component passes through zero so that the motion is entirely perpendicular or parallel to the plane of the plate. For particles on the plate surface, these conditions occur when the Lamb wave phase velocity is √2ct or cl, respectively. These directionality considerations are important when considering the radiation of acoustic energy from plates into adjacent fluids.

The particle motion is also entirely perpendicular or entirely parallel to the plane of the plate, at a mode's nascent frequency. Close to the nascent frequencies of modes corresponding to longitudinal-wave resonances of the plate, their particle motion will be almost entirely perpendicular to the plane of the plate; and near the shear-wave resonances, parallel.

J. and H. Krautkrämer have pointed out[5] that Lamb waves can be conceived as a system of longitudinal and shear waves propagating at suitable angles across and along the plate. These waves reflect and mode-convert and combine to produce a sustained, coherent wave pattern. For this coherent wave pattern to be formed, the plate thickness has to be just right relative to the angles of propagation and wavelengths of the underlying longitudinal and shear waves; this requirement leads to the velocity dispersion relationships.

Point sources and waves with cylindrical symmetry

While Lamb's analysis assumed a straight wavefront, it has been shown* that the same characteristic equations apply to axisymmetric plate waves (e.g. waves propagating with circular wavefronts from point sources, like ripples from a stone dropped into a pond). The difference is that whereas the "carrier" for the straight wavefront is a sinusoid, the "carrier" for the axisymmetric wave is a Bessel function. The Bessel function takes care of the singularity at the source, then converges towards sinusoidal behavior at great distances.

- Klaes, M, in Journées d'Etudes sur l'Emission Acoustique, INSA de Lyon (France), 1978.

Guided Lamb waves

This phrase is quite often encountered in non-destructive testing. "Guided Lamb Waves" can be defined as Lamb-like waves that are guided by the finite dimensions of real test objects. To add the prefix "guided" to the phrase "Lamb wave" is thus to recognize that Lamb's infinite plate is, in reality, nowhere to be found.

In reality we deal with finite plates, or plates wrapped into cylindrical pipes or vessels, or plates cut into thin strips, etc. Lamb wave theory often gives a very good account of much of the wave behavior of such structures. It will not give a perfect account, and that is why the phrase "Guided Lamb Waves" is more correct than "Lamb Waves". One question is how the velocities and mode shapes of the Lamb-like waves will be influenced by the real geometry of the part. For example, the velocity of a Lamb-like wave in a thin cylinder will depend slightly on the radius of the cylinder and on whether the wave is traveling along the axis or round the circumference. Another question is what completely different acoustical behaviors and wave modes may be present in the real geometry of the part. For example, a cylindrical pipe has flexural modes associated with bodily movement of the whole pipe, quite different from the Lamb-like flexural mode of the pipe wall.

Lamb waves in ultrasonic testing

The purpose of ultrasonic testing is usually to find and characterize individual flaws in the object being tested. Such flaws are detected when they reflect or scatter the impinging wave and the reflected or scattered wave reaches the search unit with sufficient amplitude.

Traditionally, ultrasonic testing has been conducted with waves whose wavelength is very much shorter than the dimension of the part being inspected. In this high-frequency-regime, the ultrasonic inspector uses waves that approximate to the infinite-medium longitudinal and shear wave modes, zig-zagging to and fro across the thickness of the plate. Although the lamb wave pioneers worked on nondestructive testing applications and drew attention to the theory, widespread use did not come about until the 1990s when computer programs for calculating dispersion curves and relating them to experimentally observable signals became much more widely available. These computational tools, along with a more widespread understanding of the nature of Lamb waves, made it possible to devise techniques for nondestructive testing using wavelengths that are comparable with or greater than the thickness of the plate. At these longer wavelengths the attenuation of the wave is less, so that flaws can be detected at greater distances.

A major challenge and skill in the use of Lamb waves for ultrasonic testing is the generation of specific modes at specific frequencies that will propagate well and give clean return "echoes". This requires careful control of the excitation. Techniques for this include the use of comb transducers, wedges, waves from liquid media and electro magnetic acoustic transducers (EMAT's).

Lamb waves in acousto-ultrasonic testing

Acousto-ultrasonic testing differs from ultrasonic testing in that it was conceived as a means of assessing damage (and other material attributes) distributed over substantial areas, rather than characterizing flaws individually. Lamb waves are well suited to this concept, because they irradiate the whole plate thickness and propagate substantial distances with consistent patterns of motion.

Lamb waves in acoustic emission testing

Acoustic emission uses much lower frequencies than traditional ultrasonic testing, and the sensor is typically expected to detect active flaws at distances up to several meters. A large fraction of the structures customarily testing with acoustic emission are fabricated from steel plate - tanks, pressure vessels, pipes and so on. Lamb wave theory is therefore the prime theory for explaining the signal forms and propagation velocities that are observed when conducting acoustic emission testing. Substantial improvements in the accuracy of AE source location (a major techniques of AE testing) can be achieved through good understanding and skillful utilization of the Lamb wave body of knowledge.

Ultrasonic and acoustic emission testing contrasted

An arbitrary mechanical excitation applied to a plate will generate a multiplicity of Lamb waves carrying energy across a range of frequencies. Such is the case for the acoustic emission wave. In acoustic emission testing, the challenge is to recognize the multiple Lamb wave components in the received waveform and to interpret them in terms of source motion. This contrasts with the situation in ultrasonic testing, where the first challenge is to generate a single, well-controlled Lamb wave mode at a single frequency. But even in ultrasonic testing, mode conversion takes place when the generated Lamb wave interacts with flaws, so the interpretation of reflected signals compounded from multiple modes becomes a means of flaw characterization.

See also

References

- ^ Achenbach, J. D. “Wave Propagation in Elastic Solids”. New York: Elsevier, 1984.

- ^ Lamb, H. "On Waves in an Elastic Plate." Proc. Roy. Soc. London, Ser. A 93, 114–128, 1917.

- ^ Viktorov, I. A. “Rayleigh and Lamb Waves: Physical Theory and Applications”, Plenum Press, New York, 1967.

- ^ This link shows a video of the particle motion.

- ^ J. and H. Krautkrämer, “Ultrasonic Testing of Materials”, 4th edition, American Society for Testing and Materials, ISBN 0318214822, April 1990.

External links

- Modes of Sound Wave Propagation at NDT Resource Center

- Lamb wave in Nondestructive Testing Encyclopedia

- Lamb Wave Analysis of Acousto-Ultrasonic Signals in Plate by Liu Zhenqing: an article which includes the complete Lamb wave equations.