Kosterlitz–Thouless transition

In statistical mechanics, a part of mathematical physics, the Kosterlitz–Thouless transition, or Berezinsky–Kosterlitz–Thouless transition, is a kind of phase transition that appears in the XY model in 2 spatial dimensions. The XY model is a 2-dimensional vector spin model that possesses U(1) or circular symmetry. This system is not expected to possess a normal second-order phase transition. This is because the expected ordered phase of the system is destroyed by transverse fluctuations, i.e. the Goldstone modes (see Goldstone boson) associated with this broken continuous symmetry, which logarithmically diverge with system size. This is a specific case of what is called the Mermin–Wagner theorem in spin systems.

The transition is named for John M. Kosterlitz, David J. Thouless, and Vadim L'vovich Berezinskiĭ (Вади́м Льво́вич Берези́нский).

Rigorously the transition is not completely understood, but the existence of two phases was proved by McBryan & Spencer (1977) and Fröhlich & Spencer (1981).

Contents |

KT Transition: disordered phases with different correlations

In the XY model in two dimensions, a second-order phase transition is not seen. However, one finds a low-temperature quasi-ordered phase with a correlation function (see statistical mechanics) that decreases with the distance like a power, which depends on the temperature. The transition from the high-temperature disordered phase with the exponential correlation to this low-temperature quasi-ordered phase is a Kosterlitz–Thouless transition. It is a phase transition of infinite order.

Role of vortices

In the 2D XY model, vortices are topologically stable configurations. It is found that the high-temperature disordered phase with exponential correlation is a result of the formation of vortices. Vortex generation becomes thermodynamically favorable at the critical temperature  of the KT transition. At temperatures below this, Vortex generation has a power law correlation.

of the KT transition. At temperatures below this, Vortex generation has a power law correlation.

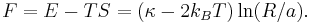

Many systems with KT transitions involve the dissociation of bound anti-parallel vortex pairs, called vortex–antivortex pairs, into unbound vortices rather than vortex generation.[1][2] In these systems, thermal generation of vortices produces an even number vortices of opposite sign. Bound vortex–antivortex pairs have lower energies than free vortices, but have lower entropy as well. In order to minimize free energy,  ,the system undergoes a transition at a critical temperature,

,the system undergoes a transition at a critical temperature,  . Below

. Below  , there are only bound vortex–antivortex pairs. Above Tc, there are free vortices.

, there are only bound vortex–antivortex pairs. Above Tc, there are free vortices.

Informal description

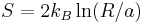

There is a very elegant thermodynamic argument for the KT transition. The energy of a single vortex is of the form  , where

, where  is a parameter depending upon the system the vortex is in,

is a parameter depending upon the system the vortex is in,  is the system size, and

is the system size, and  is the radius of the vortex core. We assume

is the radius of the vortex core. We assume  . The number of possible positions of any vortex in the system is approximately

. The number of possible positions of any vortex in the system is approximately  . From Boltzmann's law, the entropy is

. From Boltzmann's law, the entropy is  , where

, where  is Boltzmann's constant. Thus, the Helmholtz free energy is

is Boltzmann's constant. Thus, the Helmholtz free energy is

When  , the system will not have a vortex. However when

, the system will not have a vortex. However when  , the conditions are sufficient for a vortex to be in the system. We define the transition temperature for

, the conditions are sufficient for a vortex to be in the system. We define the transition temperature for  . Thus, the critical temperature

. Thus, the critical temperature  is

is

Vortices are able to form above this critical temperature, but not below. The KT transition can be observed experimentally in systems like 2D Josephson junction arrays by taking current and voltage (I-V) measurements. Above  , the relation will be linear

, the relation will be linear  . Just below

. Just below  , the relation will be

, the relation will be  , as the number of free vortices will go as

, as the number of free vortices will go as  . This jump from linear dependence is indicative of a KT transition and may be used to determine

. This jump from linear dependence is indicative of a KT transition and may be used to determine  . This approach was used in Resnic et al.[3] to confirm the KT transition in proximity-coupled Josephson junction arrays.

. This approach was used in Resnic et al.[3] to confirm the KT transition in proximity-coupled Josephson junction arrays.

Rigorous analysis

We have a field φ over the plane which takes on values in S1. For convenience, we work with its universal cover R instead but identify any two values of φ(x) which differs by an integer multiple of 2π.

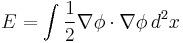

The energy is given by

and the Boltzmann factor is exp(−βE).

If we take the contour integral  over any closed path γ, we would expect it to be zero if γ is contractible, which is what we would expect for a planar curve. But here is the catch. Assume the XY theory has a UV cutoff which requires some UV completion. Then, we can have punctures in the plane, holes so to speak so that if γ is a closed path which winds once around the puncture,

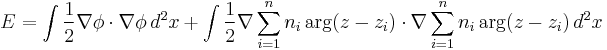

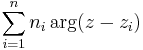

over any closed path γ, we would expect it to be zero if γ is contractible, which is what we would expect for a planar curve. But here is the catch. Assume the XY theory has a UV cutoff which requires some UV completion. Then, we can have punctures in the plane, holes so to speak so that if γ is a closed path which winds once around the puncture,  is only an integer multiple of 2π. These punctures are called vortices and if γ is a closed path which only winds once counterclockwise around the puncture and its winding number about any other puncture is zero, then the integer multiplicity can be attached to the vortex itself. Let's say a field configuration has n punctures at xi, i = 1, ..., n with multiplicities ni. Then, φ decomposes into the sum of a field configuration with no punctures, φ0 and

is only an integer multiple of 2π. These punctures are called vortices and if γ is a closed path which only winds once counterclockwise around the puncture and its winding number about any other puncture is zero, then the integer multiplicity can be attached to the vortex itself. Let's say a field configuration has n punctures at xi, i = 1, ..., n with multiplicities ni. Then, φ decomposes into the sum of a field configuration with no punctures, φ0 and  where we have switched to the complex plane coordinates for convenience. The latter term has branch cuts, of course, but since φ is only defined modulo 2π they are unphysical.

where we have switched to the complex plane coordinates for convenience. The latter term has branch cuts, of course, but since φ is only defined modulo 2π they are unphysical.

Now,

It's easy to see that unless  , the second term is positive infinite, making the Boltzmann factor zero which means that we can forget all about it.

, the second term is positive infinite, making the Boltzmann factor zero which means that we can forget all about it.

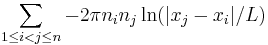

When  , the second term is equal to

, the second term is equal to  .

.

This is nothing other than a Coulomb gas. The scale L contributes nothing but a constant.

Let's look at the case with only one vortex of multiplicity one and one vortex of multiplicity -1. At low temperatures, i.e. large β, because of the Boltzmann factor, the vortex–antivortex pair tends to be extremely close to one another. In fact, their separation would be around the cutoff scale. With more vortex–antivortex pairs, we have a collection of vortex-antivortex dipoles. At large temperatures, i.e. small β, the probability distribution swings the other way around and we have a plasma of vortices and antivortices. The phase transition between the two is the Kosterlitz–Thouless phase transition.

See also

- Goldstone boson

- Ising model

- Lambda transition

- Potts model

- Quantum vortex

- Superfluid film

- Topological defect

Notes

- ^ Resnick et al,Phys. Rev Lett. 47, 1542 (1981).

- ^ Z. Hadzibabic et al.: "Berezinskii–Kosterlitz–Thouless crossover in a trapped atomic gas", Nature 441, 1118 (2006)

- ^ Resnick et al,Phys. Rev Lett. 47, 1542 (1981).

References

- Resnick, D.J.; Garland, J.C.; Boyd, J.T.; Shoemaker, S.; Newrock, R.S. (1981), "Kosterlitz Thouless Transition in Proximity Coupled Superconducting Arrays", Phys. Rev Lett. 47: 1542

- Fröhlich, Jürg; Spencer, Thomas (1981), "The Kosterlitz–Thouless transition in two-dimensional abelian spin systems and the Coulomb gas", Comm. Math. Phys. 81 (4): 527–602

- Kosterlitz, J. M.; Thouless, D. J. (1973), "Ordering, metastability and phase transitions in two-dimensional systems", Journal of Physics C: Solid State Physics 6: 1181–1203, http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/0022-3719/6/7/010

- McBryan, O.; Spencer, T. (1977), Commun. Math. Phys. 53: 299

- Z. Hadzibabic et al. (2006), "Berezinskii–Kosterlitz–Thouless crossover in a trapped atomic gas", Nature 41: 1118, http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature04851

Books

- H. Kleinert, Gauge Fields in Condensed Matter, Vol. I, " SUPERFLOW AND VORTEX LINES", pp. 1–742, World Scientific (Singapore, 1989); Paperback ISBN 9971-5-0210-0 (also available online: Vol. I. Read pp. 618–688);

- H. Kleinert, Multivalued Fields in Condensed Matter, Electrodynamics, and Gravitation, World Scientific (Singapore, 2008) (also available online: here)