Kleene's T predicate

In computability theory, the T predicate, first studied by mathematician Stephen Cole Kleene, is a particular set of triples of natural numbers that is used to represent computable functions within formal theories of arithmetic. Informally, the T predicate tells whether a particular computer program will halt when run with a particular input, and the corresponding U function is used to obtain the results of the computation if the program does halt. As with the smn theorem, the original notation used by Kleene has become standard terminology for the concept.[1]

Contents |

Definition

The definition depends on a suitable Gödel numbering that assigns natural numbers to computable functions. This numbering must be sufficiently effective that, given an index of a computable function and an input to the function, it is possible to effectively simulate the computation of the function on that input. The T predicate is obtained by formalizing this simulation.

The ternary relation T1(e,i,x) takes three natural numbers as arguments. The triples of numbers (e,i,x) that belong to the relation (the ones for which T1(e,i,x) is true) are defined to be exactly the triples in which x encodes a computation history of the computable function with index e when run with input i, and the program halts as the last step of this computation history. That is, T1 first asks whether x is the Gödel number of a finite sequence 〈xj〉 of complete configurations of the Turing machine with index e, running a computation on input i. If so, T1 then asks if this sequence begins with the starting state of the computation and each successive element of the sequence corresponds to a single step of the Turing machine. If it does, T1 finally asks whether the sequence 〈xj〉 ends with the machine in a halting state. If all three of these questions have a positive answer, then T1(e,i,x) holds (is true). Otherwise, T1(e,i,x) does not hold (is false).

There is a corresponding function U such that if T(e,i,x) holds then U(x) returns the output of the function with index e on input i.

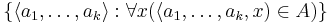

Because Kleene's formalism attaches a number of inputs to each function, the predicate T1 can only be used for functions that take one input. There are additional predicates for functions with multiple inputs; the relation

,

,

holds if x encodes a halting computation of the function with index e on the inputs i1,...,ik.

Normal form theorem

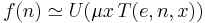

The T predicate can be used to obtain Kleene's normal form theorem for computable functions (Soare 1987, p. 15). This states that a function f(n) is computable if and only if there is an e such that for all n,

,

,

where μ is the μ operator and  holds if both sides are undefined or if both are defined and they are equal.

holds if both sides are undefined or if both are defined and they are equal.

Formalization

The T predicate is primitive recursive in the sense that there is a primitive recursive function that, given inputs for the predicate, correctly determine the truth value of the predicate on those inputs. Similarly, the U function is primitive recursive.

Because of this, any theory of arithmetic that is able to represent every primitive recursive function is able to represent T and U. Examples of such arithmetical theories include Robinson arithmetic and stronger theories such as Peano arithmetic.

Arithmetical hierarchy

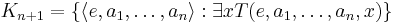

In addition to encoding computability, the T predicate can be used to generate complete sets in the arithmetical hierarchy. In particular, the set

- K = { e : ∃ x T(e,0,x)},

which is of the same Turing degree as the halting problem, is a  complete unary relation (Soare 1987, pp. 28, 41). More generally, the set

complete unary relation (Soare 1987, pp. 28, 41). More generally, the set

is a  complete (n+1)-ary predicate. Thus, once a representation of the T predicate is obtained in a theory of arithmetic, a representation of a

complete (n+1)-ary predicate. Thus, once a representation of the T predicate is obtained in a theory of arithmetic, a representation of a  -complete predicate can be obtained from it.

-complete predicate can be obtained from it.

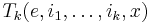

This construction can be extended higher in the arithmetical hierarchy, as in Post's theorem (compare Hinman 2005, p. 397). For example, if a set  is

is  complete then the set

complete then the set

is  complete.

complete.

Notes

- ^ The predicate described here was presented in (Kleene 1943) and (Kleene 1952), and this is what is usually called "Kleene's T predicate". (Kleene 1967) uses the letter T to describe a different predicate related to computable functions, but which cannot be used to obtain Kleene's normal form theorem.

References

- Peter Hinman, 2005, Fundamentals of Mathematical Logic, A K Peters. ISBN 978-1-56881-262-5

- Stephen Cole Kleene, 1943, "Recursive predicates and quantifiers", Transactions of the AMS v. 53 n. 1, pp. 41–73. Reprinted in The Undecidable, Martin Davis, ed., 1965, pp. 255–287.

- —, 1952, Introduction to Metamathematics, North-Holland. Reprinted by Ishi press, 2009, ISBN 0-923891-57-9.

- —, 1967. Mathematical Logic, John Wiley. Reprinted by Dover, 2001, ISBN 0-486425-33-9.

- Robert I. Soare, 1987, Recursively enumerable sets and degrees, Perspectives in Mathematical Logic, Springer. ISBN 0-387-15299-7