Kernel (matrix)

In linear algebra, the kernel or null space (also nullspace) of a matrix A is the set of all vectors x for which Ax = 0. The kernel of a matrix with n columns is a linear subspace of n-dimensional Euclidean space.[1] The dimension of the null space of A is called the nullity of A.

If viewed as a linear transformation, the null space of a matrix is precisely the kernel of the mapping (i.e. the set of vectors that map to zero). For this reason, the kernel of a linear transformation between abstract vector spaces is sometimes referred to as the null space of the transformation.

Contents |

Definition

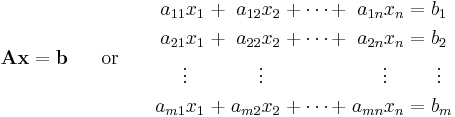

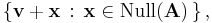

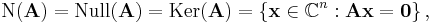

The kernel of an m × n matrix A is the set

where 0 denotes the zero vector with m components. The matrix equation Ax = 0 is equivalent to a homogeneous system of linear equations:

From this viewpoint, the null space of A is the same as the solution set to the homogeneous system.

Example

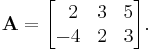

Consider the matrix

The null space of this matrix consists of all vectors (x, y, z) ∈ R3 for which

This can be written as a homogeneous system of linear equations involving x, y, and z:

This can be written in matrix form as:

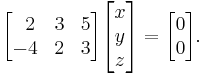

Using Gauss-Jordan reduction, this reduces to:

Rewriting yields:

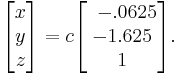

Now we can write the null space (solution to Ax = 0) in terms of c (which is our free variable), where c is scalar:

The null space of A is precisely the set of solutions to these equations (in this case, a line through the origin in R3).

Subspace properties

The null space of an m × n matrix is a subspace of Rn. That is, the set Null(A) has the following three properties:

- Null(A) always contains the zero vector.

- If x ∈ Null(A) and y ∈ Null(A), then x + y ∈ Null(A).

- If x ∈ Null(A) and c is a scalar, then c x ∈ Null(A).

Here are the proofs:

- A0 = 0.

- If Ax = 0 and Ay = 0, then A(x + y) = Ax + Ay = 0 + 0 = 0.

- If Ax = 0 and c is a scalar, then A(cx) = cAx = c0 = 0.

Basis

The null space of a matrix is not affected by elementary row operations. This makes it possible to use row reduction to find a basis for the null space:

- Input An m × n matrix A.

- Output A basis for the null space of A

- Use elementary row operations to put A in reduced row echelon form.

- Interpreting the reduced row echelon form as a homogeneous linear system, determine which of the variables x1, x2, ..., xn are free. Write equations for the dependent variables in terms of the free variables.

- For each free variable xi, choose the vector in the null space for which xi = 1 and the remaining free variables are zero. The resulting collection of vectors is a basis for the null space of A.

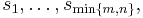

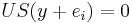

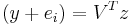

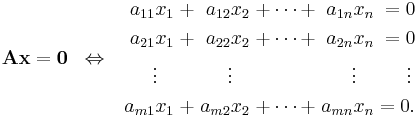

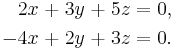

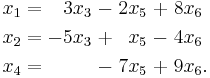

For example, suppose that the reduced row echelon form of A is

Then the solutions to the homogeneous system given in parametric form with x3, x5, and x6 as free variables are

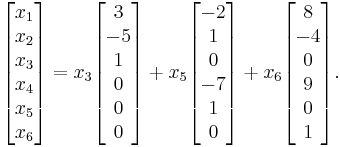

Which can be rewritten as

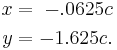

Therefore, the three vectors

are a basis for the null space of A.

Relation to the row space

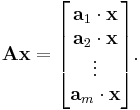

Let A be an m by n matrix (i.e., A has m rows and n columns). The product of A and the n-dimensional vector x can be written in terms of the dot product of vectors as follows:

Here a1, ..., am denote the rows of the matrix A. It follows that x is in the null space of A if and only if x is orthogonal (or perpendicular) to each of the row vectors of A (because if the dot product of two vectors is equal to zero they are by definition orthogonal).

The row space of a matrix A is the span of the row vectors of A. By the above reasoning, the null space of A is the orthogonal complement to the row space. That is, a vector x lies in the null space of A if and only if it is perpendicular to every vector in the row space of A.

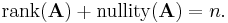

The dimension of the row space of A is called the rank of A, and the dimension of the null space of A is called the nullity of A. These quantities are related by the equation

The equation above is known as the rank-nullity theorem.

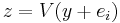

Nonhomogeneous equations

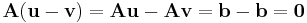

The null space also plays a role in the solution to a nonhomogeneous system of linear equations:

If u and v are two possible solutions to the above equation, then

Thus, the difference of any two solutions to the equation Ax = b lies in the null space of A.

It follows that any solution to the equation Ax = b can be expressed as the sum of a fixed solution v and an arbitrary element of the null space. That is, the solution set to the equation Ax = b is

where v is any fixed vector satisfying Av = b. Geometrically, this says that the solution set to Ax = b is the translation of the null space of A by the vector v. See also Fredholm alternative.

Left null space

The left null space of a matrix A consists of all vectors x such that xTA = 0T, where T denotes the transpose of a column vector. The left null space of A is the same as the null space of AT. The left null space of A is the orthogonal complement to the column space of A, and is the cokernel of the associated linear transformation. The null space, the row space, the column space, and the left null space of A are the four fundamental subspaces associated to the matrix A.

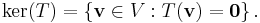

Null space of a transformation

If V and W are vector spaces, the null space (or kernel) of a linear transformation T: V → W is the set of all vectors in V that map to zero:

If we represent the linear transformation by a matrix, then the kernel of the transformation is precisely the null space of the matrix.

Numerical computation of null space

Algorithms based on row or column reduction, that is, Gaussian elimination, presented in introductory linear algebra textbooks and in the preceding sections of this article are not suitable for a practical computation of the null space because of numerical accuracy problems in the presence of rounding errors. Namely, the computation may greatly amplify the rounding errors, which are inevitable in all but textbook examples on integers, and so give completely wrong results. For this reason, methods based on introductory linear algebra texts are generally not suitable for implementation in software; rather, one should consult contemporary numerical analysis sources for an algorithm like the one below, which does not amplify rounding errors unnecessarily.

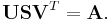

A state-of-the-art approach is based on singular value decomposition (SVD). This approach can be also easily programmed using standard libraries, such as LAPACK. SVD of matrix A computes unitary matrices U and V and a rectangular diagonal matrix S of the same size as A with nonnegative diagonal entries, such that

Denote the columns of V by

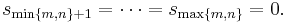

the diagonal entries of S by

and put

(The numbers  are called the singular values of A.) Then the columns

are called the singular values of A.) Then the columns  of V such that the corresponding

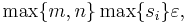

of V such that the corresponding  form an orthonormal basis of the nullspace of A. This can be seen as follows: First note that if we have one solution y of the equation

form an orthonormal basis of the nullspace of A. This can be seen as follows: First note that if we have one solution y of the equation  , then also

, then also  for unit vectors

for unit vectors  with

with  . Now if we solve

. Now if we solve  for z, then

for z, then  because of

because of  , which means that the i'th column of V spans one direction of the null space.

, which means that the i'th column of V spans one direction of the null space.

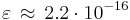

In a numerical computation, the singular values  are taken to be zero when they are less than some small tolerance. For example, the tolerance can be taken to be

are taken to be zero when they are less than some small tolerance. For example, the tolerance can be taken to be

where  is the machine epsilon of the computer, that is, the smallest number such that in the floating point arithmetics of the computer,

is the machine epsilon of the computer, that is, the smallest number such that in the floating point arithmetics of the computer,  . For the IEEE 64 bit floating point format,

. For the IEEE 64 bit floating point format,  .

.

Computation of the SVD of a matrix generally costs about the same as several matrix-matrix multiplications with matrices of the same size when state-of-the art implementation (accurate up to rounding precision) is used, such as in LAPACK. This is true even if, in theory, the SVD cannot be computed by a finite number of operations, so an iterative method with stopping tolerances based on rounding precision must be employed. The cost of the SVD approach is several times higher than computing the null space by reduction, but it should be acceptable whenever reliability is important. It is also possible to compute the null space by the QR decomposition, with the numerical stability and the cost both being between those of the SVD and the reduction approaches. The computation of a null space basis using the QR decomposition is explained in more detail below.

Let A be a mxn matrix with m < n. Using the QR factorization of  , we can find a matrix such that

, we can find a matrix such that

![\mathbf{A}^T \, \mathbf{P} = \mathbf{Q} \, \mathbf{R} = [\mathbf{Q}_1 \; \mathbf{Q}_2] \, \mathbf{R}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/e99e9f648067bd8635d8684beb3200dd.png) ,

,

where P is a permutation matrix, Q is nxn and R is nxm. Matrix  is nxm and consists of the first m columns of Q. Matrix

is nxm and consists of the first m columns of Q. Matrix  is nx(n-m) and is made up of Q 's last n-m columns. Since

is nx(n-m) and is made up of Q 's last n-m columns. Since  , the columns of

, the columns of  span the null space of A.

span the null space of A.

See also

- Matrix (mathematics)

- Kernel (algebra)

- Euclidean subspace

- System of linear equations

- Row space

- Column space or Image (matrix)

- Row reduction

- Four fundamental subspaces

Notes

- ^ Linear algebra, as discussed in this article, is a very well-established mathematical discipline for which there are many sources. Almost all of the material in this article can be found in Lay 2005, Meyer 2001, and Strang 2005.

- ^ This equation uses set-builder notation.

References

Textbooks

- Axler, Sheldon Jay (1997), Linear Algebra Done Right (2nd ed.), Springer-Verlag, ISBN 0387982590

- Lay, David C. (August 22, 2005), Linear Algebra and Its Applications (3rd ed.), Addison Wesley, ISBN 978-0321287137

- Meyer, Carl D. (February 15, 2001), Matrix Analysis and Applied Linear Algebra, Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics (SIAM), ISBN 978-0898714548, http://www.matrixanalysis.com/DownloadChapters.html

- Poole, David (2006), Linear Algebra: A Modern Introduction (2nd ed.), Brooks/Cole, ISBN 0-534-99845-3

- Anton, Howard (2005), Elementary Linear Algebra (Applications Version) (9th ed.), Wiley International

- Leon, Steven J. (2006), Linear Algebra With Applications (7th ed.), Pearson Prentice Hall

Numerical analysis textbooks

- Lloyd N. Trefethen and David Bau, III, Numerical Linear Algebra, SIAM 1997, ISBN 978-0898713619 online version

External links

- Gilbert Strang, MIT Linear Algebra Lecture on the Four Fundamental Subspaces at Google Video, from MIT OpenCourseWare

|

|||||

![\left[\begin{array}{ccc|c}

2 & 3 & 5 & 0 \\

-4 & 2 & 3 & 0

\end{array}\right].](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/d257b6062253b08015413efa76c79d3e.png)

![\left[\begin{array}{ccc|c}

1 & 0 & .0625 & 0 \\

0 & 1 & 1.625 & 0

\end{array}\right].](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/28ea31b68b2d55bda4c4e0d8738ec042.png)

![\left[ \begin{alignat}{6}

1 && 0 && -3 && 0 && 2 && -8 \\

0 && 1 && 5 && 0 && -1 && 4 \\

0 && 0 && 0 && 1 && 7 && -9 \\

0 && \;\;\;\;\;0 && \;\;\;\;\;0 && \;\;\;\;\;0 && \;\;\;\;\;0 && \;\;\;\;\;0 \end{alignat} \,\right]\text{.}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/befae7065923f09a02a345a14b9f4447.png)

![\left[\!\! \begin{array}{r} 3 \\ -5 \\ 1 \\ 0 \\ 0 \\ 0 \end{array} \right],\;

\left[\!\! \begin{array}{r} -2 \\ 1 \\ \mathbf{0} \\ -7 \\ \mathbf{1} \\ \mathbf{0} \end{array} \right],\;

\left[\!\! \begin{array}{r} 8 \\ -4 \\ \mathbf{0} \\ 9 \\ \mathbf{0} \\ \mathbf{1} \end{array} \right]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/da816610f5a918cf91d1e57519fef2bf.png)