Karush–Kuhn–Tucker conditions

In mathematics, the Karush–Kuhn–Tucker (KKT) conditions (also known as the Kuhn–Tucker conditions) are necessary for a solution in nonlinear programming to be optimal, provided that some regularity conditions are satisfied. Allowing inequality constraints, the KKT approach to nonlinear programming generalizes the method of Lagrange multipliers, which allows only equality constraints. The KKT conditions were originally named after Harold W. Kuhn, and Albert W. Tucker, who first published the conditions.[1] Later scholars discovered that the necessary conditions for this problem had been stated by William Karush in his master's thesis.[2][3]

Contents |

Nonlinear optimization problem

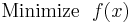

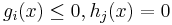

We consider the following nonlinear optimization problem:

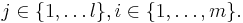

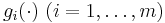

where x is the optimization variable,  is the objective or cost function,

is the objective or cost function,  are the inequality constraint functions, and

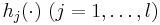

are the inequality constraint functions, and  are the equality constraint functions. The number of inequality and equality constraints are denoted m and l, respectively.

are the equality constraint functions. The number of inequality and equality constraints are denoted m and l, respectively.

Necessary conditions

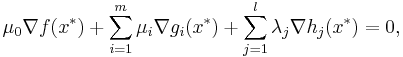

Suppose that the objective function  and the constraint functions

and the constraint functions  and

and  are continuously differentiable at a point

are continuously differentiable at a point  . If

. If  is a local minimum that satisfies some regularity conditions (see below), then there exist constants

is a local minimum that satisfies some regularity conditions (see below), then there exist constants  and

and  , called KKT multipliers, such that

, called KKT multipliers, such that

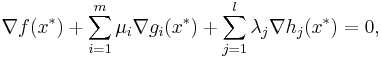

- Stationarity

- Primal feasibility

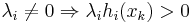

- Dual feasibility

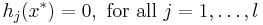

- Complementary slackness

In the particular case  , i.e., when there are no inequality constraints, the KKT conditions turn into the Lagrange conditions, and the KKT multipliers are called Lagrange multipliers.

, i.e., when there are no inequality constraints, the KKT conditions turn into the Lagrange conditions, and the KKT multipliers are called Lagrange multipliers.

Regularity conditions (or constraint qualifications)

In order for a minimum point  to satisfy the above KKT conditions, it should satisfy some regularity condition, the most used ones are listed below:

to satisfy the above KKT conditions, it should satisfy some regularity condition, the most used ones are listed below:

- Linear independence constraint qualification (LICQ): the gradients of the active inequality constraints and the gradients of the equality constraints are linearly independent at

.

. - Mangasarian–Fromovitz constraint qualification (MFCQ): the gradients of the active inequality constraints and the gradients of the equality constraints are positive-linearly independent at

.

. - Constant rank constraint qualification (CRCQ): for each subset of the gradients of the active inequality constraints and the gradients of the equality constraints the rank at a vicinity of

is constant.

is constant. - Constant positive linear dependence constraint qualification (CPLD): for each subset of the gradients of the active inequality constraints and the gradients of the equality constraints, if it is positive-linear dependent at

then it is positive-linear dependent at a vicinity of

then it is positive-linear dependent at a vicinity of  .

. - Quasi-normality constraint qualification (QNCQ): if the gradients of the active inequality constraints and the gradients of the equality constraints are positive-linearly independent at

with associated multipliers

with associated multipliers  for equalities and

for equalities and  for inequalities, then there is no sequence

for inequalities, then there is no sequence  such that

such that  and

and  .

. - Slater condition: for a convex problem, there exists a point

such that

such that  and

and  for all

for all  active in

active in  .

. - Linearity constraints: If

and

and  are affine functions, then no other condition is needed to assure that the minimum point is KKT.

are affine functions, then no other condition is needed to assure that the minimum point is KKT.

( ) is positive-linear dependent if there exists

) is positive-linear dependent if there exists  not all zero such that

not all zero such that  .

.

It can be shown that LICQ⇒MFCQ⇒CPLD⇒QNCQ, LICQ⇒CRCQ⇒CPLD⇒QNCQ (and the converses are not true), although MFCQ is not equivalent to CRCQ[4] . In practice weaker constraint qualifications are preferred since they provide stronger optimality conditions.

Sufficient conditions

In some cases, the necessary conditions are also sufficient for optimality. In general, the necessary conditions are not sufficient for optimality and additional information is necessary, such as the Second Order Sufficient Conditions (SOSC). For smooth functions, SOSC involve the second derivatives, which explains its name.

The necessary conditions are sufficient for optimality if the objective function  and the inequality constraints

and the inequality constraints  are continuously differentiable convex functions and the equality constraints

are continuously differentiable convex functions and the equality constraints  are affine functions.

are affine functions.

It was shown by Martin in 1985[5] that the broader class of functions in which KKT conditions guarantees global optimality are the so called Type 1 invex functions.[6]

Value function

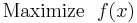

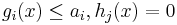

If we reconsider the optimization problem as a maximization problem with constant inequality constraints,

The value function is defined as:

(So the domain of V is  )

)

Given this definition, each coefficient,  , is the rate at which the value function increases as

, is the rate at which the value function increases as  increases. Thus if each

increases. Thus if each  is interpreted as a resource constraint, the coefficients tell you how much increasing a resource will increase the optimum value of our function f. This interpretation is especially important in economics and is used, for instance, in utility maximization problems.

is interpreted as a resource constraint, the coefficients tell you how much increasing a resource will increase the optimum value of our function f. This interpretation is especially important in economics and is used, for instance, in utility maximization problems.

Generalizations

With an extra constant multiplier  , which may be zero, in front of

, which may be zero, in front of  the KKT stationarity conditions turn into

the KKT stationarity conditions turn into

which are called the Fritz John conditions.

The KKT conditions belong to a wider class of the First Order Necessary Conditions (FONC), which allow for non-smooth functions using subderivatives.

See also

References

- ^ Kuhn, H. W.; Tucker, A. W. (1951). "Nonlinear programming". Proceedings of 2nd Berkeley Symposium. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 481–492. http://projecteuclid.org/euclid.bsmsp/1200500249. MR47303

- ^ W. Karush (1939). Minima of Functions of Several Variables with Inequalities as Side Constraints. M.Sc. Dissertation. Dept. of Mathematics, Univ. of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois.

- ^ Kjeldsen, Tinne Hoff. "A contextualized historical analysis of the Kuhn-Tucker theorem in nonlinear programming: the impact of World War II". Historia Math. 27 (2000), no. 4, 331–361. MR1800317

- ^ Rodrigo Eustaquio, Elizabeth Karas, and Ademir Ribeiro. Constraint Qualification for Nonlinear Programming (Technical report). Federal University of Parana. http://pessoal.utfpr.edu.br/eustaquio/arquivos/kkt.pdf.

- ^ Martin, D. H. (1985). "The essence of invexity". J. Optim. Theory Appl., 47. pp. 65–76.

- ^ M.A. Hanson, Invexity and the Kuhn-Tucker Theorem, J. Math. Anal. Appl. vol. 236, pp. 594–604 (1999)

Further reading

- R. Andreani, J. M. Martínez, M. L. Schuverdt, On the relation between constant positive linear dependence condition and quasinormality constraint qualification. Journal of Optimization Theory and Applications, vol. 125, no2, pp. 473–485 (2005).

- Avriel, Mordecai (2003). Nonlinear Programming: Analysis and Methods. Dover Publishing. ISBN 0-486-43227-0.

- J. Nocedal, S. J. Wright, Numerical Optimization. Springer Publishing. ISBN 978-0-387-30303-1.