Kaluza–Klein theory

| Beyond the Standard Model |

|---|

| Standard Model |

|

Theories

Technicolor

Kaluza–Klein theory Grand Unified Theory Theory of everything String theory Superfluid vacuum theory |

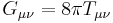

In physics, Kaluza–Klein theory (KK theory) is a model that seeks to unify the two fundamental forces of gravitation and electromagnetism. The theory was first published in 1921. It was proposed by the mathematician Theodor Kaluza who extended general relativity to a five-dimensional spacetime. The resulting equations can be separated into further sets of equations, one of which is equivalent to Einstein field equations, another set equivalent to Maxwell's equations for the electromagnetic field and the final part an extra scalar field now termed the "radion".

Contents |

Overview

A splitting of five-dimensional spacetime into the Einstein equations and Maxwell equations in four dimensions was first discovered by Gunnar Nordström in 1914, in the context of his theory of gravity, but subsequently forgotten. Kaluza published his derivation in 1921 as an attempt to unify electromagnetism with Einstein's general relativity.

In 1926, Oskar Klein proposed that the fourth spatial dimension is curled up in a circle of very small radius, so that a particle moving a short distance along that axis would return to where it began. The distance a particle can travel before reaching its initial position is said to be the size of the dimension. This extra dimension is a compact set, and the phenomenon of having a space-time with compact dimensions is referred to as compactification.

In modern geometry, the extra fifth dimension can be understood to be the circle group U(1), as electromagnetism can essentially be formulated as a gauge theory on a fiber bundle, the circle bundle, with gauge group U(1). In Kaluza-Klein theory this group suggests that gauge symmetry is the symmetry of circular compact dimensions. Once this geometrical interpretation is understood, it is relatively straightforward to replace U(1) by a general Lie group. Such generalizations are often called Yang–Mills theories. If a distinction is drawn, then it is that Yang–Mills theories occur on a flat space-time, whereas Kaluza–Klein treats the more general case of curved spacetime. The base space of Kaluza–Klein theory need not be four-dimensional space-time; it can be any (pseudo-)Riemannian manifold, or even a supersymmetric manifold or orbifold or even a noncommutative space.

As an approach to the unification of the forces, it is straightforward to apply the Kaluza–Klein theory in an attempt to unify gravity with the strong and electroweak forces by using the symmetry group of the Standard Model, SU(3) × SU(2) × U(1). However, an attempt to convert this interesting geometrical construction into a bona-fide model of reality flounders on a number of issues, including the fact that the fermions must be introduced in an artificial way (in nonsupersymmetric models). Nonetheless, KK remains an important touchstone in theoretical physics and is often embedded in more sophisticated theories. It is studied in its own right as an object of geometric interest in K-theory.

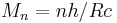

Even in the absence of a completely satisfying theoretical physics framework, the idea of exploring extra, compactified, dimensions is of considerable interest in the experimental physics and astrophysics communities. A variety of predictions, with real experimental consequences, can be made (in the case of large extra dimensions/warped models). For example, on the simplest of principles, one might expect to have standing waves in the extra compactified dimension(s). If a spatial extra dimension is of radius R, the invariant mass of such standing waves would be  with n an integer, h being Planck's constant and c the speed of light. This set of possible mass values is often called the Kaluza–Klein tower. Similarly, in Thermal quantum field theory a compactification of the euclidean time dimension leads to the Matsubara frequencies and thus to a discretized thermal energy spectrum.

with n an integer, h being Planck's constant and c the speed of light. This set of possible mass values is often called the Kaluza–Klein tower. Similarly, in Thermal quantum field theory a compactification of the euclidean time dimension leads to the Matsubara frequencies and thus to a discretized thermal energy spectrum.

Examples of experimental pursuits include work by the CDF collaboration, which has re-analyzed particle collider data for the signature of effects associated with large extra dimensions/warped models.

Brandenberger and Vafa have speculated that in the early universe, cosmic inflation causes three of the space dimensions to expand to cosmological size while the remaining dimensions of space remained microscopic.

Space-time-matter theory

One particular variant of Kaluza–Klein theory is space-time-matter theory or induced matter theory, chiefly promulgated by Paul Wesson and other members of the so-called Space-Time-Matter Consortium.[1] In this version of the theory, it is noted that solutions to the equation

with  the five-dimensional Ricci curvature, may be re-expressed so that in four dimensions, these solutions satisfy Einstein's equations

the five-dimensional Ricci curvature, may be re-expressed so that in four dimensions, these solutions satisfy Einstein's equations

with the precise form of the  following from the Ricci-flat condition on the five-dimensional space. Since the energy-momentum tensor

following from the Ricci-flat condition on the five-dimensional space. Since the energy-momentum tensor  is normally understood to be due to concentrations of matter in four-dimensional space, the above result is interpreted as saying that four-dimensional matter is induced from geometry in five-dimensional space.

is normally understood to be due to concentrations of matter in four-dimensional space, the above result is interpreted as saying that four-dimensional matter is induced from geometry in five-dimensional space.

In particular, the soliton solutions of  can be shown to contain the Friedmann-Lemaitre-Robertson-Walker metric in both radiation-dominated (early universe) and matter-dominated (later universe) forms. The general equations can be shown to be sufficiently consistent with classical tests of general relativity to be acceptable on physical principles, while still leaving considerable freedom to also provide interesting cosmological models.

can be shown to contain the Friedmann-Lemaitre-Robertson-Walker metric in both radiation-dominated (early universe) and matter-dominated (later universe) forms. The general equations can be shown to be sufficiently consistent with classical tests of general relativity to be acceptable on physical principles, while still leaving considerable freedom to also provide interesting cosmological models.

Geometric interpretation

The Kaluza–Klein theory is striking because it has a particularly elegant presentation in terms of geometry. In a certain sense, it looks just like ordinary gravity in free space, except that it is phrased in five dimensions instead of four.

The Einstein equations

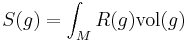

The equations governing ordinary gravity in free space can be obtained from an action, by applying the variational principle to a certain action. Let M be a (pseudo-)Riemannian manifold, which may be taken as the spacetime of general relativity. If g is the metric on this manifold, one defines the action  as

as

where R(g) is the scalar curvature and vol(g) is the volume element. By applying the variational principle to the action

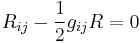

one obtains precisely the Einstein equations for free space:

Here,  is the Ricci tensor.

is the Ricci tensor.

The Maxwell equations

By contrast, the Maxwell equations describing electromagnetism can be understood to be the Hodge equations of a principal U(1)-bundle or circle bundle  with fiber U(1). That is, the electromagnetic field F is a harmonic 2-form in the space

with fiber U(1). That is, the electromagnetic field F is a harmonic 2-form in the space  of differentiable 2-forms on the manifold M. In the absence of charges and currents, the free-field Maxwell equations are

of differentiable 2-forms on the manifold M. In the absence of charges and currents, the free-field Maxwell equations are

and

and

where  is the Hodge star.

is the Hodge star.

The Kaluza–Klein geometry

To build the Kaluza–Klein theory, one picks an invariant metric on the circle  that is the fiber of the U(1)-bundle of electromagnetism. In this discussion, an invariant metric is simply one that is invariant under rotations of the circle. Suppose this metric gives the circle a total length of

that is the fiber of the U(1)-bundle of electromagnetism. In this discussion, an invariant metric is simply one that is invariant under rotations of the circle. Suppose this metric gives the circle a total length of  . One then considers metrics

. One then considers metrics  on the bundle P that are consistent with both the fiber metric, and the metric on the underlying manifold M. The consistency conditions are:

on the bundle P that are consistent with both the fiber metric, and the metric on the underlying manifold M. The consistency conditions are:

- The projection of

to the vertical subspace

to the vertical subspace  needs to agree with metric on the fiber over a point in the manifold M.

needs to agree with metric on the fiber over a point in the manifold M.

- The projection of

to the horizontal subspace

to the horizontal subspace  of the tangent space at point

of the tangent space at point  must be isomorphic to the metric g on M at

must be isomorphic to the metric g on M at  .

.

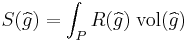

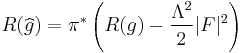

The Kaluza–Klein action for such a metric is given by

The scalar curvature, written in components, then expands to

where  is the pullback of the fiber bundle projection

is the pullback of the fiber bundle projection  . The connection A on the fiber bundle is related to the electromagnetic field strength as

. The connection A on the fiber bundle is related to the electromagnetic field strength as

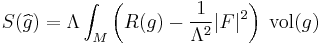

That there always exists such a connection, even for fiber bundles of arbitrarily complex topology, is a result from homology and specifically, K-theory. Applying Fubini's theorem and integrating on the fiber, one gets

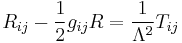

Varying the action with respect to the component A, one regains the Maxwell equations. Applying the variational principle to the base metric g, one gets the Einstein equations

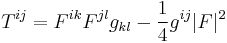

with the stress-energy tensor being given by

,

,

sometimes called the Maxwell stress tensor.

The original theory identifies  with the fiber metric

with the fiber metric  , and allows

, and allows  to vary from fiber to fiber. In this case, the coupling between gravity and the electromagnetic field is not constant, but has its own dynamical field, the radion.

to vary from fiber to fiber. In this case, the coupling between gravity and the electromagnetic field is not constant, but has its own dynamical field, the radion.

Commentary and generalizations

In the above, the size of the loop  acts as a coupling constant between the gravitational field and the electromagnetic field. If the base manifold is four-dimensional, the Kaluza–Klein manifold P is five-dimensional. The fifth dimension is a compact space, and is called the compact dimension. The technique of introducing compact dimensions to obtain a higher-dimensional manifold is referred to as compactification. Compactification does not produce group actions on chiral fermions except in very specific cases: the dimension of the total space must be 2 mod 8 and the G-index of the Dirac operator of the compact space must be nonzero.[2]

acts as a coupling constant between the gravitational field and the electromagnetic field. If the base manifold is four-dimensional, the Kaluza–Klein manifold P is five-dimensional. The fifth dimension is a compact space, and is called the compact dimension. The technique of introducing compact dimensions to obtain a higher-dimensional manifold is referred to as compactification. Compactification does not produce group actions on chiral fermions except in very specific cases: the dimension of the total space must be 2 mod 8 and the G-index of the Dirac operator of the compact space must be nonzero.[2]

The above development generalizes in a more-or-less straightforward fashion to general principal G-bundles for some arbitrary Lie group G taking the place of U(1). In such a case, the theory is often referred to as a Yang-Mills theory, and is sometimes taken to be synonymous. If the underlying manifold is supersymmetric, the resulting theory is a supersymmetric Yang–Mills theory.

Empirical tests

Up to now, no experimental or observational signs of extra dimensions have been officially reported. An analysis of results from the Large Hadron Collider in December 2010 severely constrains theories with large extra dimensions.[3]

See also

- Classical theories of gravitation

- DGP model

- Randall-Sundrum model

- Supergravity

- Superstring theory

- Why 10 dimensions?

- Quantum gravity

References

- ^ http://astro.uwaterloo.ca/~wesson/

- ^ L. Castellani et al., Supergravity and superstrings, Vol 2, chapter V.11

- ^ CMS Collaoration, "Search for Microscopic Black Hole Signatures at the Large Hadron Collider," http://arxiv.org/abs/1012.3375

- Nordström, Gunnar (1914). "Über die Möglichkeit, das elektromagnetische Feld und das Gravitationsfeld zu vereinigen". Physikalische Zeitschrift 15: 504–506. OCLC 1762351.

- Kaluza, Theodor (1921). "Zum Unitätsproblem in der Physik". Sitzungsber. Preuss. Akad. Wiss. Berlin. (Math. Phys.) 1921: 966–972.

- Klein, Oskar (1926). "Quantentheorie und fünfdimensionale Relativitätstheorie". Zeitschrift für Physik A 37 (12): 895–906. Bibcode 1926ZPhy...37..895K. doi:10.1007/BF01397481.

- Witten, Edward (1981). "Search for a realistic Kaluza-Klein theory". Nuclear Physics B 186 (3): 412–428. Bibcode 1981NuPhB.186..412W. doi:10.1016/0550-3213(81)90021-3.

- Appelquist, Thomas; Chodos, Alan; Freund, Peter G. O. (1987). Modern Kaluza-Klein Theories. Menlo Park, Cal.: Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0201098296. (Includes reprints of the above articles as well as those of other important papers relating to Kaluza–Klein theory.)

- Brandenberger, Robert; Vafa, Cumrun (1989). "Superstrings in the early universe". Nuclear Physics B 316 (2): 391–410. Bibcode 1989NuPhB.316..391B. doi:10.1016/0550-3213(89)90037-0.

- Duff, M. J. (1994). "Kaluza-Klein Theory in Perspective". In Lindström, Ulf (ed.). Proceedings of the Symposium ‘The Oskar Klein Centenary’. Singapore: World Scientific. pp. 22–35. ISBN 9810223323.

- Overduin, J. M.; Wesson, P. S. (1997). "Kaluza-Klein Gravity". Physics Reports 283 (5): 303–378. arXiv:gr-qc/9805018. Bibcode 1997PhR...283..303O. doi:10.1016/S0370-1573(96)00046-4.

- Wesson, Paul S. (1999). Space-Time-Matter, Modern Kaluza-Klein Theory. Singapore: World Scientific. ISBN 9810235887.

- Wesson, Paul S. (2006). Five-Dimensional Physics: Classical and Quantum Consequences of Kaluza-Klein Cosmology. Singapore: World Scientific. ISBN 9812566619.

Further reading

- Grøn, Øyvind; Hervik, Sigbjørn (2007). Einstein's General Theory of Relativity. New York: Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-69199-2.

- Kaku, Michio and Robert O'Keefe. Hyperspace: A Scientific Odyssey Through Parallel Universes, Time Warps, and the Tenth Dimension. New York: Oxford University Press, 1994. ISBN 0-19-286189-1

- The CDF Collaboration, Search for Extra Dimensions using Missing Energy at CDF, (2004) (A simplified presentation of the search made for extra dimensions at the Collider Detector at Fermilab (CDF) particle physics facility.)

- John M. Pierre, SUPERSTRINGS! Extra Dimensions, (2003).

- TeV scale gravity, mirror universe, and ... dinosaurs Article from Acta Physica Polonica B by Z.K. Silagadze.

- Chris Pope, Lectures on Kaluza-Klein Theory.

|

|||||||||