James Hopwood Jeans

| James Hopwood Jeans | |

|---|---|

| Born | 11 September 1877 Ormskirk, Lancashire, England |

| Died | 16 September 1946 (aged 69) Dorking, Surrey, England |

| Nationality | British |

| Fields | astronomy, mathematics, physics |

| Institutions | Trinity College, Cambridge; Princeton University |

| Alma mater | Merchant Taylors' School; Cambridge University |

| Doctoral students | Ronald Fisher |

| Known for | Rayleigh–Jeans law, Astronomer Royal |

Sir James Hopwood Jeans OM FRS[1] MA DSc ScD LLD [2] (11 September 1877 – 16 September 1946[3]) was an English physicist, astronomer and mathematician.

Contents |

Background

Born in Ormskirk, Lancashire, Jeans was educated at Merchant Taylors' School, Northwood, Wilson's Grammar School,[4] Camberwell and Trinity College, Cambridge,[5] he finished Second Wrangler in the university in the Mathematical Tripos of 1898. He taught at Cambridge, but went to Princeton University in 1904 as a professor of applied mathematics. He returned to Cambridge in 1910.

He made important contributions in many areas of physics, including quantum theory, the theory of radiation and stellar evolution. His analysis of rotating bodies led him to conclude that Laplace's theory that the solar system formed from a single cloud of gas was incorrect, proposing instead that the planets condensed from material drawn out of the sun by a hypothetical catastrophic near-collision with a passing star. This theory is not accepted today.

Jeans, along with Arthur Eddington, is a founder of British cosmology. In 1928 Jeans was the first to conjecture a steady state cosmology based on a hypothesized continuous creation of matter in the universe.[6] This theory was ruled out when the 1965 discovery of the cosmic microwave background was widely interpreted as the tell-tale signature of the Big Bang.

His scientific reputation is grounded in the monographs The Dynamical Theory of Gases (1904), Theoretical Mechanics (1906), and Mathematical Theory of Electricity and Magnetism (1908). After retiring in 1929, he wrote a number of books for the lay public, including The Stars in Their Courses (1931), The Universe Around Us, Through Space and Time (1934), The New Background of Science (1933), and The Mysterious Universe. These books made Jeans fairly well known as an expositor of the revolutionary scientific discoveries of his day, especially in relativity and physical cosmology.

In 1939, the Journal of the British Astronomical Association reported that Jeans was going to stand as a candidate for parliament for the Cambridge University constituency. The election, expected to take place in 1939 or 1940 did not take place until 1945, and without his involvement.

He also wrote the book "Physics and Philosophy" (1943) where he explores the different views on reality from two different perspectives: science and philosophy.

Jeans married twice, first to the American poet Charlotte Tiffany Mitchell in 1907,[7] then the Austrian organist and harpsichordist Suzanne Hock (better known as Susi Jeans) in 1935. He died in Dorking, Surrey.

At Merchant Taylors' School there is a James Jeans Academic Scholarship for the candidate in the entrance exams who displays outstanding results across the spectrum of subjects but notably in Mathematics and Sciences.

Tidal Hypothesis

The Tidal or Gaseous Hypothesis of the earth involves an original sun that had a close encounter with a passing star. Known also as the tidal disruption or tidal filament hypothesis, this conception of how our solar system formed was proposed in 1918 by two British scientists, Sir James Jeans and Sir Harold Jeffreys. Jeans, an astronomer, and Jeffreys, a geophysicist, offered this proposal to counteract some of the objections that had been raised to the planetesimal hypothesis. They accepted the supposed near-collision between the sun and another star but believed that the material pulled out of the sun came out as a long spindle or cigar-shaped filament of solar gases. This gaseous filament later broke up into units which condensed to a molten and finally a solid stage, thus forming the planets. Astronomers have shown that a gaseous filament of this sort would not form solid bodies such as our planets; it would instead simply disappear in space. For this and many other reasons, this hypothesis is no longer acceptable to most scientists.

Idealism

For an overview see Idealism.

The stream of knowledge is heading towards a non-mechanical reality; the Universe begins to look more like a great thought than like a great machine. Mind no longer appears to be an accidental intruder into the realm of matter... we ought rather hail it as the creator and governor of the realm of matter. Sir James Jeans "The mysterious universe" page 137.

Sir James Jeans, in an interview published in The Observer (London), when asked the question:

Do you believe that life on this planet is the result of some sort of accident, or do you believe that it is a part of some great scheme?

replied:

I incline to the idealistic theory that consciousness is fundamental, and that the material universe is derivative from consciousness, not consciousness from the material universe... In general the universe seems to me to be nearer to a great thought than to a great machine. It may well be, it seems to me, that each individual consciousness ought to be compared to a brain-cell in a universal mind.

What remains is in any case very different from the full-blooded matter and the forbidding materialism of the Victorian scientist. His objective and material universe is proved to consist of little more than constructs of our own minds. To this extent, then, modem physics has moved in the direction of philosophic idealism. Mind and matter, if not proved to be of similar nature, are at least found to be ingredients of one single system. There is no longer room for the kind of dualism which has haunted philosophy since the days of Descartes. Sir James Jeans addressing the British Association in 1934.

Finite picture whose dimensions are a certain amount of space and a certain amount of time; the protons and electrons are the streaks of paint which define the picture against its space-time background. Traveling as far back in time as we can, brings us not to the creation of the picture, but to its edge; the creation of the picture lies as much outside the picture as the artist is outside his canvas. On this view, discussing the creation of the universe in terms of time and space is like trying to discover the artist and the action of painting, by going to the edge of the canvas. This brings us very near to those philosophical systems which regard the universe as a thought in the mind of its Creator, thereby reducing all discussion of material creation to futility. Sir James Jeans "The universe around us" page 317.

Major accomplishments

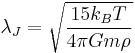

One of Jeans' major discoveries, named Jeans length, is a critical radius of an interstellar cloud in space. It depends on the temperature, and density of the cloud, and the mass of the particles composing the cloud. A cloud that is smaller than its Jeans length will not have sufficient gravity to overcome the repulsive gas pressure forces and condense to form a star, whereas a cloud that is larger than its Jeans length will collapse.

Jeans came up with another version of this equation, called Jeans mass or Jeans instability, that solves for the critical mass a cloud must attain before being able to collapse.

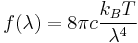

Jeans also helped to discover the Rayleigh–Jeans law, which relates the energy density of blackbody radiation to the temperature of the emission source.

Books

Available online from the Internet Archive:

- 1904. The Dynamical Theory of Gases

- 1906. Theoretical Mechanics

- 1908. Mathematical Theory of Electricity and Magnetism

Other:

- 1929. The Universe Around Us

- 1930. The Mysterious Universe

- 1931. The Stars in Their Courses

- 1933. The New Background of Science

- 1937. Science and Music

- 1942. Physics and Philosophy

Awards and honours

- Fellow of the Royal Society in May, 1906

- Bakerian Lecture to Royal Society in 1917.

- Royal Medal of the Royal Society in 1919.

- Hopkins Prize of the Cambridge Philosophical Society 1921–1924.

- Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1922.

- He was knighted in 1928.

- Franklin Medal of the Franklin Institute in 1931.

- Mukerjee Medal of the Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science in 1937.

- President of the 25th session of the Indian Science Congress in 1938.

- Calcutta Medal of the Indian Science Congress Association in 1938.

- Member of the Order of Merit in 1939.

- The crater Jeans on the Moon is named after him, as is the crater Jeans on Mars.

- The String Quartet No.7 by Robert Simpson was written in tribute to him on the centenary of his birth, 1977.

See also

References

- ^ Milne, E. A. (1947). "James Hopwood Jeans. 1877-1946". Obituary Notices of Fellows of the Royal Society 5 (15): 573–570. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1947.0019.

- ^ Sir James Jeans 1938 (reprint of 1931's edition of 1930 book): The Mysterious Universe.

- ^ GRO Register of Deaths: SEP 1946 5g 607 SURREY SE – James H. Jeans, aged 69

- ^ Allport, D.H. & Friskney, N.J. "A Short History of Wilson's School", Wilson's School Charitable Trust, 1987, pg 234

- ^ Jeans, James Hopwood in Venn, J. & J. A., Alumni Cantabrigienses, Cambridge University Press, 10 vols, 1922–1958.

- ^ Astronomy and Cosmogony, Cambridge U Press, p 360

- ^ J J O'Connor and E F Robertson (October 2003). "Sir James Hopwood Jeans". School of Mathematics and Statistics, University of St Andrews, Scotland. http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Jeans.html. Retrieved November 28, 2011.

Bibliography

- Jeans, James Hopwood. (1947). The Growth of Physical Science. Cambridge University Press (reissued by Cambridge University Press, 2009; ISBN 9781108005654)

- Jeans, James Hopwood. (1942). Physics and Philosophy. Cambridge University Press (reissued by Cambridge University Press, 2009; ISBN 9781108005678)

- Jeans, James Hopwood. (1940). An Introduction to the Kinetic Theory of Gases. Cambridge University Press (reissued by Cambridge University Press, 2009; ISBN 9781108005609)

- Jeans, James Hopwood. (1937). Science and Music. Cambridge University Press (reissued by Cambridge University Press, 2009; ISBN 9781108005692)

- Jeans, James Hopwood. (1934). Through Space and Time. Cambridge University Press (reissued by Cambridge University Press, 2009; ISBN 9781108005715)

- Jeans, James Hopwood. (1933). The New Background of Science. Cambridge University Press (reissued by Cambridge University Press, 2009; ISBN 9781108005722)

- Jeans, James Hopwood. (1931). Stars in Their Courses. Cambridge University Press (reissued by Cambridge University Press, 2009; ISBN 9781108005708)

- Jeans, James Hopwood. (1930). The Mysterious Universe. Cambridge University Press (reissued by Cambridge University Press, 2009; ISBN 9781108005661)

- Jeans, James Hopwood. (1928). Astronomy and Cosmogony. Cambridge University Press (reissued by Cambridge University Press, 2009; ISBN 9781108005623)

- Jeans, James Hopwood. (1925). Mathematical Theory of Electricity and Magnetism. Cambridge University Press (reissued by Cambridge University Press, 2009; ISBN 9781108005616)

- Jeans, James Hopwood. (1926). Atomicity and Quanta. Cambridge University Press (reissued by Cambridge University Press, 2009; ISBN 9781108005630)

- Jeans, James Hopwood. (1919). Problems of Cosmology and Stellar Dynamics. Cambridge University Press (reissued by Cambridge University Press, 2009; ISBN 9781108005685)

- Jeans, James Hopwood. (1904). The Dynamical Theory of Gases. Cambridge University Press (reissued by Cambridge University Press, 2009; ISBN 9781108005647)

External links

- MacTutor (St. Andrews Univ.): More biographical information., including photos

- Britannica article includes photo