Intersection (set theory)

In mathematics, the intersection (denoted as ∩) of two sets A and B is the set that contains all elements of A that also belong to B (or equivalently, all elements of B that also belong to A), but no other elements.[1]

For explanation of the symbols used in this article, refer to the table of mathematical symbols.

Contents |

Basic definition

The intersection of A and B is written "A ∩ B". Formally:

- x ∈ A ∩ B if and only if

- x ∈ A and

- x ∈ B.

- For example:

- The intersection of the sets {1, 2, 3} and {2, 3, 4} is {2, 3}.

- The number 9 is not in the intersection of the set of prime numbers {2, 3, 5, 7, 11, …} and the set of odd numbers {1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, …}.

If the intersection of two sets A and B is empty, that is they have no elements in common, then they are said to be disjoint, denoted: A ∩ B = ∅. For example the sets {1, 2} and {3, 4} are disjoint, written

{1, 2} ∩ {3, 4} = ∅.

More generally, one can take the intersection of several sets at once. The intersection of A, B, C, and D, for example, is A ∩ B ∩ C ∩ D = A ∩ (B ∩ (C ∩ D)). Intersection is an associative operation; thus,

A ∩ (B ∩ C) = (A ∩ B) ∩ C.

If the sets A and B are closed under complement then the intersection of A and B may be written as the complement of the union of their complements, derived easily from De Morgan's laws:

A ∩ B = (Ac ∪ Bc)c

Arbitrary intersections

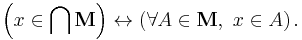

The most general notion is the intersection of an arbitrary nonempty collection of sets. If M is a nonempty set whose elements are themselves sets, then x is an element of the intersection of M if and only if for every element A of M, x is an element of A. In symbols:

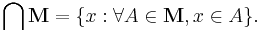

The notation for this last concept can vary considerably. Set theorists will sometimes write "⋂M", while others will instead write "⋂A∈M A". The latter notation can be generalized to "⋂i∈I Ai", which refers to the intersection of the collection {Ai : i ∈ I}. Here I is a nonempty set, and Ai is a set for every i in I.

In the case that the index set I is the set of natural numbers, notation analogous to that of an infinite series may be seen:

When formatting is difficult, this can also be written "A1 ∩ A2 ∩ A3 ∩ ...", even though strictly speaking, A1 ∩ (A2 ∩ (A3 ∩ ... makes no sense. (This last example, an intersection of countably many sets, is actually very common; for an example see the article on σ-algebras.)

Finally, let us note that whenever the symbol "∩" is placed before other symbols instead of between them, it should be of a larger size (⋂).

Nullary intersection

Note that in the previous section we excluded the case where M was the empty set (∅). The reason is as follows: The intersection of the collection M is defined as the set (see set-builder notation)

If M is empty there are no sets A in M, so the question becomes "which x's satisfy the stated condition?" The answer seems to be every possible x. When M is empty the condition given above is an example of a vacuous truth. So the intersection of the empty family should be the universal set, which according to standard (ZFC) set theory, does not exist.

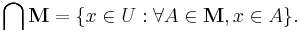

A partial fix for this problem can be found if we agree to restrict our attention to subsets of a fixed set U called the universe. In this case the intersection of a family of subsets of U can be defined as

Now if M is empty there is no problem. The intersection is just the entire universe U, which is a well-defined set by assumption.