Inner product space

In mathematics, an inner product space is a vector space with an additional structure called an inner product. This additional structure associates each pair of vectors in the space with a scalar quantity known as the inner product of the vectors. Inner products allow the rigorous introduction of intuitive geometrical notions such as the length of a vector or the angle between two vectors. They also provide the means of defining orthogonality between vectors (zero inner product). Inner product spaces generalize Euclidean spaces (in which the inner product is the dot product, also known as the scalar product) to vector spaces of any (possibly infinite) dimension, and are studied in functional analysis.

An inner product naturally induces an associated norm, thus an inner product space is also a normed vector space. A complete space with an inner product is called a Hilbert space. An incomplete space with an inner product is called a pre-Hilbert space, since its completion with respect to the norm, induced by the inner product, becomes a Hilbert space. Inner product spaces over the field of complex numbers are sometimes referred to as unitary spaces.

Contents |

Definition

In this article, the field of scalars denoted  is either the field of real numbers

is either the field of real numbers  or the field of complex numbers

or the field of complex numbers  .

.

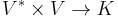

Formally, an inner product space is a vector space V over the field  together with an inner product, i.e., with a map

together with an inner product, i.e., with a map

that satisfies the following three axioms for all vectors  and all scalars

and all scalars  :[1][2]

:[1][2]

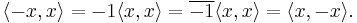

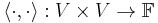

- Conjugate symmetry:

Note that in  , it is symmetric.

, it is symmetric.

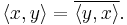

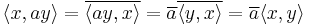

- Linearity in the first argument:

-

with equality only for

with equality only for

Notice that conjugate symmetry implies that  is real for all

is real for all  , since we have

, since we have

Moreover, sesquilinearity (see below) implies that

Conjugate symmetry and linearity in the first variable gives

so an inner product is a sesquilinear form. Conjugate symmetry is also called Hermitian symmetry, and a conjugate symmetric sesquilinear form is called a Hermitian form. While the above axioms are more mathematically economical, a compact verbal definition of an inner product is a positive-definite Hermitian form.

In the case of  , conjugate-symmetry reduces to symmetry, and sesquilinear reduces to bilinear. So, an inner product on a real vector space is a positive-definite symmetric bilinear form.

, conjugate-symmetry reduces to symmetry, and sesquilinear reduces to bilinear. So, an inner product on a real vector space is a positive-definite symmetric bilinear form.

From the linearity property it is derived that  implies

implies  while from the positive-definiteness axiom we obtain the converse,

while from the positive-definiteness axiom we obtain the converse,  implies

implies  Combining these two, we have the property that

Combining these two, we have the property that  if and only if

if and only if

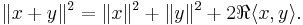

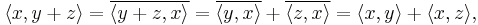

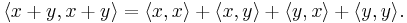

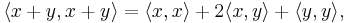

Combining the linearity of the inner product in its first argument and the conjugate symmetry gives the following important generalization of the familiar square expansion:

Assuming that the underlying field is  , the inner product becomes symmetric, and we obtain

, the inner product becomes symmetric, and we obtain

or similarly,

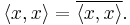

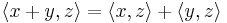

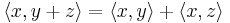

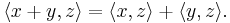

The property of an inner product space  that

that

-

and

and

is also known as additivity.

Remark: Some authors, especially in physics and matrix algebra, prefer to define the inner product and the sesquilinear form with linearity in the second argument rather than the first. Then the first argument becomes conjugate linear, rather than the second. In those disciplines we would write the product  as

as  (the bra-ket notation of quantum mechanics), respectively

(the bra-ket notation of quantum mechanics), respectively  (dot product as a case of the convention of forming the matrix product AB as the dot products of rows of A with columns of B). Here the kets and columns are identified with the vectors of V and the bras and rows with the dual vectors or linear functionals of the dual space V*, with conjugacy associated with duality. This reverse order is now occasionally followed in the more abstract literature, e.g., Emch [1972], taking

(dot product as a case of the convention of forming the matrix product AB as the dot products of rows of A with columns of B). Here the kets and columns are identified with the vectors of V and the bras and rows with the dual vectors or linear functionals of the dual space V*, with conjugacy associated with duality. This reverse order is now occasionally followed in the more abstract literature, e.g., Emch [1972], taking  to be conjugate linear in x rather than y. A few instead find a middle ground by recognizing both

to be conjugate linear in x rather than y. A few instead find a middle ground by recognizing both  and

and  as distinct notations differing only in which argument is conjugate linear.

as distinct notations differing only in which argument is conjugate linear.

There are various technical reasons why it is necessary to restrict the basefield to  and

and  in the definition. Briefly, the basefield has to contain an ordered subfield (in order for non-negativity to make sense) and therefore has to have characteristic equal to 0. This immediately excludes finite fields. The basefield has to have additional structure, such as a distinguished automorphism. More generally any quadratically closed subfield of

in the definition. Briefly, the basefield has to contain an ordered subfield (in order for non-negativity to make sense) and therefore has to have characteristic equal to 0. This immediately excludes finite fields. The basefield has to have additional structure, such as a distinguished automorphism. More generally any quadratically closed subfield of  or

or  will suffice for this purpose, e.g., the algebraic numbers, but when it is a proper subfield (i.e., neither

will suffice for this purpose, e.g., the algebraic numbers, but when it is a proper subfield (i.e., neither  nor

nor  ) even finite-dimensional inner product spaces will fail to be metrically complete. In contrast all finite-dimensional inner product spaces over

) even finite-dimensional inner product spaces will fail to be metrically complete. In contrast all finite-dimensional inner product spaces over  or

or  , such as those used in quantum computation, are automatically metrically complete and hence Hilbert spaces.

, such as those used in quantum computation, are automatically metrically complete and hence Hilbert spaces.

In some cases we need to consider non-negative semi-definite sesquilinear forms. This means that  is only required to be non-negative. We show how to treat these below.

is only required to be non-negative. We show how to treat these below.

Examples

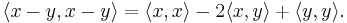

- A simple example is the real numbers with the standard multiplication as the inner product

-

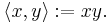

- More generally any Euclidean space

n with the dot product is an inner product space

n with the dot product is an inner product space

- The general form of an inner product on

n is given by:

n is given by:

-

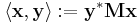

- with M any Hermitian positive-definite matrix, and y* the conjugate transpose of y. For the real case this corresponds to the dot product of the results of directionally differential scaling of the two vectors, with positive scale factors and orthogonal directions of scaling. Up to an orthogonal transformation it is a weighted-sum version of the dot product, with positive weights.

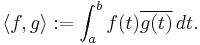

- The article on Hilbert space has several examples of inner product spaces wherein the metric induced by the inner product yields a complete metric space. An example of an inner product which induces an incomplete metric occurs with the space C[a, b] of continuous complex valued functions on the interval [a, b]. The inner product is

-

- This space is not complete; consider for example, for the interval [−1,1] the sequence of "step" functions { fk }k where

- fk(t) is 0 for t in the subinterval [−1,0]

- fk(t) is 1 for t in the subinterval [1/k, 1]

- fk is affine in [0, 1/k].

- This sequence is a Cauchy sequence which does not converge to a continuous function.

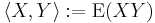

- For random variables X and Y, the expected value of their product

-

- is an inner product. In this case, <X, X>=0 if and only if Pr(X=0)=1 (i.e., X=0 almost surely). This definition of expectation as inner product can be extended to random vectors as well.

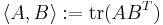

- For square real matrices,

with transpose as conjugation

with transpose as conjugation  is an inner product.

is an inner product.

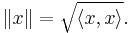

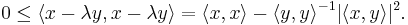

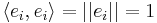

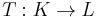

Norms on inner product spaces

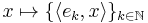

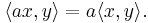

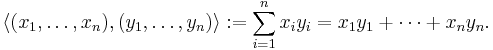

A linear space with a norm such as:

where p ≠ 2 is a normed space but not an inner product space, because this norm does not satisfy the parallelogram equality required of a norm to have an inner product associated with it.[3][4]

However, inner product spaces have a naturally defined norm based upon the inner product of the space itself that does satisfy the parallelogram equality:

This is well defined by the nonnegativity axiom of the definition of inner product space. The norm is thought of as the length of the vector x. Directly from the axioms, we can prove the following:

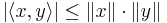

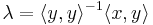

- Cauchy–Schwarz inequality: for x, y elements of V

- with equality if and only if x and y are linearly dependent. This is one of the most important inequalities in mathematics. It is also known in the Russian mathematical literature as the Cauchy–Bunyakowski–Schwarz inequality.

- Because of its importance, its short proof should be noted.

-

- It is trivial to prove the inequality true in the case y = 0. Thus we assume ⟨y, y⟩ is nonzero, giving us the following:

-

- The complete proof can be obtained by multiplying out this result.

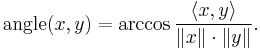

- Orthogonality: The geometric interpretation of the inner product in terms of angle and length, motivates much of the geometric terminology we use in regard to these spaces. Indeed, an immediate consequence of the Cauchy-Schwarz inequality is that it justifies defining the angle between two non-zero vectors x and y in the case F =

by the identity

by the identity

- We assume the value of the angle is chosen to be in the interval [0, +π]. This is in analogy to the situation in two-dimensional Euclidean space.

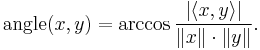

- In the case F =

, the angle in the interval [0, +π/2] is typically defined by

, the angle in the interval [0, +π/2] is typically defined by

- Correspondingly, we will say that non-zero vectors x and y of V are orthogonal if and only if their inner product is zero.

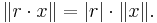

- Homogeneity: for x an element of V and r a scalar

- The homogeneity property is completely trivial to prove.

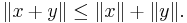

- Triangle inequality: for x, y elements of V

- The last two properties show the function defined is indeed a norm.

- Because of the triangle inequality and because of axiom 2, we see that ||·|| is a norm which turns V into a normed vector space and hence also into a metric space. The most important inner product spaces are the ones which are complete with respect to this metric; they are called Hilbert spaces. Every inner product V space is a dense subspace of some Hilbert space. This Hilbert space is essentially uniquely determined by V and is constructed by completing V.

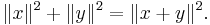

- Pythagorean theorem: Whenever x, y are in V and ⟨x, y⟩ = 0, then

- The proof of the identity requires only expressing the definition of norm in terms of the inner product and multiplying out, using the property of additivity of each component.

- The name Pythagorean theorem arises from the geometric interpretation of this result as an analogue of the theorem in synthetic geometry. Note that the proof of the Pythagorean theorem in synthetic geometry is considerably more elaborate because of the paucity of underlying structure. In this sense, the synthetic Pythagorean theorem, if correctly demonstrated is deeper than the version given above.

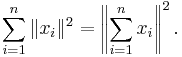

- An induction on the Pythagorean theorem yields:

- If x1, ..., xn are orthogonal vectors, that is,

for distinct indices j, k, then

for distinct indices j, k, then

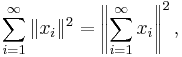

- In view of the Cauchy-Schwarz inequality, we also note that

is continuous from V × V to F. This allows us to extend Pythagoras' theorem to infinitely many summands:

is continuous from V × V to F. This allows us to extend Pythagoras' theorem to infinitely many summands:

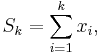

- Parseval's identity: Suppose V is a complete inner product space. If {xk} are mutually orthogonal vectors in V then

- provided the infinite series on the left is convergent. Completeness of the space is needed to ensure that the sequence of partial sums

- which is easily shown to be a Cauchy sequence, is convergent.

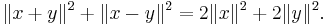

- Parallelogram law: for x, y elements of V,

The Parallelogram law is, in fact, a necessary and sufficient condition for the existence of a scalar product corresponding to a given norm. If it holds, the scalar product is defined by the polarization identity:

- which is a form of the law of cosines.

Orthonormal sequences

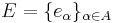

Let V be a finite dimensional inner product space of dimension n. Recall that every basis of V consists of exactly n linearly independent vectors. Using the Gram-Schmidt Process we may start with an arbitrary basis and transform it into an orthonormal basis. That is, into a basis in which all the elements are orthogonal and have unit norm. In symbols, a basis  is orthonormal if

is orthonormal if  if

if  and

and  for each i.

for each i.

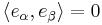

This definition of orthonormal basis generalizes to the case of infinite dimensional inner product spaces in the following way. Let V be a any inner product space. Then a collection  is a basis for V if the subspace of V generated by finite linear combinations of elements of E is dense in V (in the norm induced by the inner product). We say that E is an orthonormal basis for V if it is a basis and

is a basis for V if the subspace of V generated by finite linear combinations of elements of E is dense in V (in the norm induced by the inner product). We say that E is an orthonormal basis for V if it is a basis and  if

if  and

and  for all

for all  .

.

Using an infinite-dimensional analog of the Gram-Schmidt process one may show:

Theorem. Any separable inner product space V has an orthonormal basis.

Using the Hausdorff Maximal Principle and the fact that in a complete inner product space orthogonal projection onto linear subspaces is well-defined, one may also show that

Theorem. Any complete inner product space V has an orthonormal basis.

The two previous theorems raise the question of whether all inner product spaces have an orthonormal basis. The answer, it turns out is negative. This is a non-trivial result, and is proved below. The following proof is taken from Halmos's A Hilbert Space Problem Book (see the references).

-

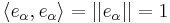

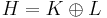

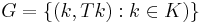

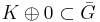

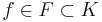

Proof Recall that the dimension of an inner product space is the cardinality of a maximal orthonormal system that it contains (by Zorn's lemma it contains at least one, and any two have the same cardinality). An orthonormal basis is certainly a maximal orthonormal system, but as we shall see, the converse need not hold. Observe that if G is a dense subspace of an inner product space H, then any orthonormal basis for G is automatically an orthonormal basis for H. Thus, it suffices to construct an inner product space space H with a dense subspace G whose dimension is strictly smaller than that of H. Let K be a Hilbert space of dimension

(for instance,

(for instance,  ). Let E be an orthonormal basis of K, so

). Let E be an orthonormal basis of K, so  . Extend E to a Hamel basis

. Extend E to a Hamel basis  for K, where

for K, where  . Since it is known that the Hamel dimension of K is c, the cardinality of the continuum, it must be that

. Since it is known that the Hamel dimension of K is c, the cardinality of the continuum, it must be that  .

.Let L be a Hilbert space of dimension c (for instance,

). Let B be an orthonormal basis for L, and let

). Let B be an orthonormal basis for L, and let  be a bijection. Then there is a linear transformation

be a bijection. Then there is a linear transformation  such that

such that  for

for  , and

, and  for

for  .

.Let

and let

and let  be the graph of T. Let

be the graph of T. Let  be the closure of G in H; we will show

be the closure of G in H; we will show  . Since for any

. Since for any  we have

we have  , it follows that

, it follows that  .

.Next, if

, then

, then  for some

for some  , so

, so  ; since

; since  as well, we also have

as well, we also have  . It follows that

. It follows that  , so

, so  , and G is dense in H.

, and G is dense in H.Finally,

is a maximal orthonormal set in G; if

is a maximal orthonormal set in G; iffor all

then certainly

then certainly  , so

, so  is the zero vector in G. Hence the dimension of G is

is the zero vector in G. Hence the dimension of G is  , whereas it is clear that the dimension of H is c. This completes the proof.

, whereas it is clear that the dimension of H is c. This completes the proof.

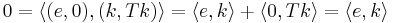

Parseval's identity leads immediately to the following theorem:

Theorem. Let V be a separable inner product space and {ek}k an orthonormal basis of V. Then the map

is an isometric linear map V → ℓ 2 with a dense image.

This theorem can be regarded as an abstract form of Fourier series, in which an arbitrary orthonormal basis plays the role of the sequence of trigonometric polynomials. Note that the underlying index set can be taken to be any countable set (and in fact any set whatsoever, provided ℓ 2 is defined appropriately, as is explained in the article Hilbert space). In particular, we obtain the following result in the theory of Fourier series:

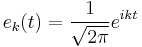

Theorem. Let V be the inner product space ![C[-\pi,\pi]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/8844ac48264a6497b40d9944f38b443b.png) . Then the sequence (indexed on set of all integers) of continuous functions

. Then the sequence (indexed on set of all integers) of continuous functions

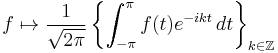

is an orthonormal basis of the space ![C[-\pi,\pi]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/8844ac48264a6497b40d9944f38b443b.png) with the L2 inner product. The mapping

with the L2 inner product. The mapping

is an isometric linear map with dense image.

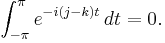

Orthogonality of the sequence {ek}k follows immediately from the fact that if k ≠ j, then

Normality of the sequence is by design, that is, the coefficients are so chosen so that the norm comes out to 1. Finally the fact that the sequence has a dense algebraic span, in the inner product norm, follows from the fact that the sequence has a dense algebraic span, this time in the space of continuous periodic functions on ![[-\pi,\pi]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/911bebeafbf3d4845e122edfc4f667f8.png) with the uniform norm. This is the content of the Weierstrass theorem on the uniform density of trigonometric polynomials.

with the uniform norm. This is the content of the Weierstrass theorem on the uniform density of trigonometric polynomials.

Operators on inner product spaces

Several types of linear maps A from an inner product space V to an inner product space W are of relevance:

- Continuous linear maps, i.e., A is linear and continuous with respect to the metric defined above, or equivalently, A is linear and the set of non-negative reals {||Ax||}, where x ranges over the closed unit ball of V, is bounded.

- Symmetric linear operators, i.e., A is linear and ⟨Ax, y⟩ = ⟨x, A y⟩ for all x, y in V.

- Isometries, i.e., A is linear and ⟨Ax, Ay⟩ = ⟨x, y⟩ for all x, y in V, or equivalently, A is linear and ||Ax|| = ||x|| for all x in V. All isometries are injective. Isometries are morphisms between inner product spaces, and morphisms of real inner product spaces are orthogonal transformations (compare with orthogonal matrix).

- Isometrical isomorphisms, i.e., A is an isometry which is surjective (and hence bijective). Isometrical isomorphisms are also known as unitary operators (compare with unitary matrix).

From the point of view of inner product space theory, there is no need to distinguish between two spaces which are isometrically isomorphic. The spectral theorem provides a canonical form for symmetric, unitary and more generally normal operators on finite dimensional inner product spaces. A generalization of the spectral theorem holds for continuous normal operators in Hilbert spaces.

Generalizations

Any of the axioms of an inner product may be weakened, yielding generalized notions. The generalizations that are closest to inner products occur where bilinearity and conjugate symmetry are retained, but positive-definiteness is weakened.

Degenerate inner products

If V is a vector space and  a semi-definite sesquilinear form, then the function ‖x‖ =

a semi-definite sesquilinear form, then the function ‖x‖ =  makes sense and satisfies all the properties of norm except that ‖x‖ = 0 does not imply x = 0 (such a functional is then called a semi-norm). We can produce an inner product space by considering the quotient W = V/{ x : ‖x‖ = 0}. The sesquilinear form

makes sense and satisfies all the properties of norm except that ‖x‖ = 0 does not imply x = 0 (such a functional is then called a semi-norm). We can produce an inner product space by considering the quotient W = V/{ x : ‖x‖ = 0}. The sesquilinear form  factors through W.

factors through W.

This construction is used in numerous contexts. The Gelfand–Naimark–Segal construction is a particularly important example of the use of this technique. Another example is the representation of semi-definite kernels on arbitrary sets.

Nondegenerate conjugate symmetric forms

Alternatively, one may require that the pairing be a nondegenerate form, meaning that for all non-zero x there exists some y such that  though y need not equal x; in other words, the induced map to the dual space

though y need not equal x; in other words, the induced map to the dual space  is injective. This generalization is important in differential geometry: a manifold whose tangent spaces have an inner product is a Riemannian manifold, while if this is related to nondegenerate conjugate symmetric form the manifold is a pseudo-Riemannian manifold. By Sylvester's law of inertia, just as every inner product is similar to the dot product with positive weights on a set of vectors, every nondegenerate conjugate symmetric form is similar to the dot product with nonzero weights on a set of vectors, and the number of positive and negative weights are called respectively the positive index and negative index.

is injective. This generalization is important in differential geometry: a manifold whose tangent spaces have an inner product is a Riemannian manifold, while if this is related to nondegenerate conjugate symmetric form the manifold is a pseudo-Riemannian manifold. By Sylvester's law of inertia, just as every inner product is similar to the dot product with positive weights on a set of vectors, every nondegenerate conjugate symmetric form is similar to the dot product with nonzero weights on a set of vectors, and the number of positive and negative weights are called respectively the positive index and negative index.

Purely algebraic statements (ones that do not use positivity) usually only rely on the nondegeneracy (the injective homomorphism  ) and thus hold more generally.

) and thus hold more generally.

The Minkowski inner product

The Minkowski inner product is typically defined in a 4-dimensional real vector space. It satisfies all the axioms of an inner product, except that it is not positive-definite, i.e., the Minkowski norm ||v|| of a vector v, defined as ||v||2 = η(v,v), need not be positive. The positive-definite condition has been replaced by the weaker condition of nondegeneracy (every positive-definite form is nondegenerate but not vice-versa). It is common to call a Minkowski inner product an indefinite inner product, although, technically speaking, it is not an inner product according to the standard definition above.

Related products

The term "inner product" is opposed to outer product, which is a slightly more general opposite. Simply, in coordinates, the inner product is the product of a 1×n covector with an n×1 vector, yielding a 1×1 matrix (a scalar), while the outer product is the product of an m×1 vector with a 1×n covector, yielding an m×n matrix. Note that the outer product is defined for different dimensions, while the inner product requires the same dimension. If the dimensions are the same, then the inner product is the trace of the outer product (trace only being properly defined for square matrices).

On an inner product space, or more generally a vector space with a nondegenerate form (so an isomorphism  ) vectors can be sent to covectors (in coordinates, via transpose), so one can take the inner product and outer product of two vectors, not simply of a vector and a covector.

) vectors can be sent to covectors (in coordinates, via transpose), so one can take the inner product and outer product of two vectors, not simply of a vector and a covector.

In a quip: "inner is horizontal times vertical and shrinks down, outer is vertical times horizontal and expands out".

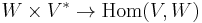

More abstractly, the outer product is the bilinear map  sending a vector and a covector to a rank 1 linear transformation (simple tensor of type (1,1)), while the inner product is the bilinear evaluation map

sending a vector and a covector to a rank 1 linear transformation (simple tensor of type (1,1)), while the inner product is the bilinear evaluation map  given by evaluating a covector on a vector; the order of the domain vector spaces here reflects the covector/vector distinction.

given by evaluating a covector on a vector; the order of the domain vector spaces here reflects the covector/vector distinction.

The inner product and outer product should not be confused with the interior product and exterior product, which are instead operations on vector fields and differential forms, or more generally on the exterior algebra.

As a further complication, in geometric algebra the inner product and the exterior (Grassmann) product are combined in the geometric product (the Clifford product in a Clifford algebra) – the inner product sends two vectors (1-vectors) to a scalar (a 0-vector), while the exterior product sends two vectors to a bivector (2-vector) – and in this context the exterior product is usually called the "outer (alternatively, wedge) product". The inner product is more correctly called a scalar product in this context, as the nondegenerate quadratic form in question need not be positive definite (need not be an inner product).

Notes and in-line references

- ^ P. K. Jain, Khalil Ahmad (1995). "5.1 Definitions and basic properties of inner product spaces and Hilbert spaces". Functional analysis (2nd ed.). New Age International. p. 203. ISBN 812240801X. http://books.google.com/?id=yZ68h97pnAkC&pg=PA203.

- ^ Eduard Prugovec̆ki (1981). "Definition 2.1". Quantum mechanics in Hilbert space (2nd ed.). Academic Press. pp. 18 ff. ISBN 012566060X. http://books.google.com/?id=GxmQxn2PF3IC&pg=PA18.

- ^ P. K. Jain, Khalil Ahmad (1995). "Example 5". Cited work. p. 209. ISBN 812240801X. http://books.google.com/?id=yZ68h97pnAkC&pg=PA209.

- ^ Karen Saxe (2002). Beginning functional analysis. Springer. p. 7. ISBN 0387952241. http://books.google.com/?id=QALoZC64ea0C&pg=PA7.

See also

- Bilinear form

- Dual space

- Dual pair

- Biorthogonal system

- Fubini–Study metric

- Energetic space

- Space (mathematics)

- Normed vector space

References

- Axler, Sheldon (1997). Linear Algebra Done Right (2nd ed.). Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-0-387-98258-8

- Emch, Gerard G. (1972). Algebraic methods in statistical mechanics and quantum field theory. Wiley-Interscience. ISBN 978-0-471-23900-0

- Young, Nicholas (1988). An introduction to Hilbert space. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-33717-5

|

|||||

![\|x\|_p = \left[ \sum_{i=1}^{\infty} |\xi_i|^p \right] ^{1/p} \ x = \{\xi_i\} \in \mathit {l}^p \ ,](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/7dc4a753bd8b85135bad9713c279b3ab.png)