Infinitesimal

Infinitesimals have been used to express the idea of objects so small that there is no way to see them or to measure them. The word infinitesimal comes from a 17th century Modern Latin coinage infinitesimus, which originally referred to the "infinite-th" item in a series.

In common speech, an infinitesimal object is an object which is smaller than any feasible measurement, but not zero in size; or, so small that it cannot be distinguished from zero by any available means. Hence, when used as an adjective, "infinitesimal" in the vernacular means "extremely small".

Archimedes used what eventually came to be known as the Method of indivisibles in his work The Method of Mechanical Theorems to find areas of regions and volumes of solids.[1] In his formal published treatises, Archimedes solved the same problem using the Method of Exhaustion. The 15th century saw the work of Nicholas of Cusa, further developed in the 17th century by Johannes Kepler, in particular calculation of area of a circle by representing the latter as an infinite-sided polygon. Simon Stevin's work on decimal representation of all numbers in the 16th century prepared the ground for the real continuum. Bonaventura Cavalieri's method of indivisibles led to an extension of the results of the classical authors. The method of indivisibles related to geometrical figures as being composed of entities of codimension 1. John Wallis's infinitesimals differed from indivisibles in that he would decompose geometrical figures into infinitely thin building blocks of the same dimension as the figure, preparing the ground for general methods of the integral calculus. He exploited an infinitesimal denoted  in area calculations.

in area calculations.

The use of infinitesimals in Leibniz relied upon a heuristic principle called the Law of Continuity: what succeeds for the finite numbers succeeds also for the infinite numbers and vice versa. The 18th century saw routine use of infinitesimals by mathematicians such as Leonhard Euler and Joseph Lagrange. Augustin-Louis Cauchy exploited infinitesimals in defining continuity and an early form of a Dirac delta function. As Cantor and Dedekind were developing more abstract versions of Stevin's continuum, Paul du Bois-Reymond wrote a series of papers on infinitesimal-enriched continua based on growth rates of functions. Du Bois-Reymond's work inspired both Émile Borel and Thoralf Skolem. Borel explicitly linked du Bois-Reymond's work to Cauchy's work on rates of growth of infinitesimals. Skolem developed the first non-standard models of arithmetic in 1934. A mathematical implementation of both the law of continuity and infinitesimals was achieved by Abraham Robinson in 1961, who developed non-standard analysis based on earlier work by Edwin Hewitt in 1948 and Jerzy Łoś in 1955. The hyperreals implement an infinitesimal-enriched continuum and the transfer principle implements Leibniz's law of continuity. The standard part function implements Fermat's adequality.

Contents |

History of the infinitesimal

The notion of infinitesimally small quantities was discussed by the Eleatic School. Archimedes, in The Method of Mechanical Theorems, was the first to propose a logically rigorous definition of infinitesimals.[2] His Archimedean property defines a number x as infinite if it satisfies the conditions |x|>1, |x|>1+1, |x|>1+1+1, ..., and infinitesimal if x≠0 and a similar set of conditions holds for 1/x and the reciprocals of the positive integers. A number system is said to be Archimedean if it contains no infinite or infinitesimal members.

The Indian mathematician Bhāskara II (1114–1185)[3] described a geometric technique for expressing the change in  in terms of

in terms of  times a change in

times a change in  . Prior to the invention of calculus mathematicians were able to calculate tangent lines by the method Pierre de Fermat's method of adequality and René Descartes method of normals. There is debate among scholars as to whether the method was infinitesimal or algebraic in nature. When Newton and Leibniz invented the calculus, they made use of infinitesimals. The use of infinitesimals was attacked as incorrect by Bishop Berkeley in his work The Analyst.[4] Mathematicians, scientists, and engineers continued to use infinitesimals to produce correct results. In the second half of the nineteenth century, the calculus was reformulated by Karl Weierstrass, Cantor, Dedekind, and others using the (ε, δ)-definition of limit and set theory. While infinitesimals eventually disappeared from the calculus, their mathematical study continued through the work of Levi-Civita and others, throughout the late nineteenth and the twentieth centuries, as documented by Ehrlich (2006). In the 20th century, it was found that infinitesimals could serve as a basis for calculus and analysis.

. Prior to the invention of calculus mathematicians were able to calculate tangent lines by the method Pierre de Fermat's method of adequality and René Descartes method of normals. There is debate among scholars as to whether the method was infinitesimal or algebraic in nature. When Newton and Leibniz invented the calculus, they made use of infinitesimals. The use of infinitesimals was attacked as incorrect by Bishop Berkeley in his work The Analyst.[4] Mathematicians, scientists, and engineers continued to use infinitesimals to produce correct results. In the second half of the nineteenth century, the calculus was reformulated by Karl Weierstrass, Cantor, Dedekind, and others using the (ε, δ)-definition of limit and set theory. While infinitesimals eventually disappeared from the calculus, their mathematical study continued through the work of Levi-Civita and others, throughout the late nineteenth and the twentieth centuries, as documented by Ehrlich (2006). In the 20th century, it was found that infinitesimals could serve as a basis for calculus and analysis.

First-order properties

In extending the real numbers to include infinite and infinitesimal quantities, one typically wishes to be as conservative as possible by not changing any of their elementary properties. This guarantees that as many familiar results as possible will still be available. Typically elementary means that there is no quantification over sets, but only over elements. This limitation allows statements of the form "for any number x..." For example, the axiom that states "for any number x, x + 0 = x" would still apply. The same is true for quantification over several numbers, e.g., "for any numbers x and y, xy = yx." However, statements of the form "for any set S of numbers ..." may not carry over. This limitation on quantification is referred to as first-order logic.

It superficially seems clear that the resulting extended number system cannot agree with the reals on all properties that can be expressed by quantification over sets, because the goal is to construct a nonarchimedean system, and the Archimedean principle can be expressed by quantification over sets, but this is just plain wrong. It is trivial to conservatively extend any theory including reals, including set theory, to include infinitesimals, just by adding a countably infinite list of axioms that assert that a number is smaller than 1/2, 1/3, 1/4 and so on. Similarly, the completeness property cannot be expected to carry over, because the reals are the unique complete ordered field up to isomorphism. This is also wrong, at least as a formal statement, since it presuming some underlying model of set theory.

We can distinguish three levels at which a nonarchimedean number system could have first-order properties compatible with those of the reals:

- An ordered field obeys all the usual axioms of the real number system that can be stated in first-order logic. For example, the commutativity axiom x + y = y + x holds.

- A real closed field has all the first-order properties of the real number system, regardless of whether they are usually taken as axiomatic, for statements involving the basic ordered-field relations +, * , and ≤. This is a stronger condition than obeying the ordered-field axioms. More specifically, one includes additional first-order properties, such as the existence of a root for every odd-degree polynomial. For example, every number must have a cube root.

- The system could have all the first-order properties of the real number system for statements involving any relations (regardless of whether those relations can be expressed using +, *, and ≤). For example, there would have to be a sine function that is well defined for infinite inputs; the same is true for every real function.

Systems in category 1, at the weak end of the spectrum, are relatively easy to construct, but do not allow a full treatment of classical analysis using infinitesimals in the spirit of Newton and Leibniz. For example, the transcendental functions are defined in terms of infinite limiting processes, and therefore there is typically no way to define them in first-order logic. Increasing the analytic strength of the system by passing to categories 2 and 3, we find that the flavor of the treatment tends to become less constructive, and it becomes more difficult to say anything concrete about the hierarchical structure of infinities and infinitesimals.

Number systems that include infinitesimals

Formal series

Laurent series

An example from category 1 above is the field of Laurent series with a finite number of negative-power terms. For example, the Laurent series consisting only of the constant term 1 is identified with the real number 1, and the series with only the linear term x is thought of as the simplest infinitesimal, from which the other infinitesimals are constructed. Dictionary ordering is used, which is equivalent to considering higher powers of x as negligible compared to lower powers. David O. Tall[5] refers to this system as the super-reals, not to be confused with the superreal number system of Dales and Woodin. Since a Taylor series evaluated with a Laurent series as its argument is still a Laurent series, the system can be used to do calculus on transcendental functions if they are analytic. These infinitesimals have different first-order properties than the reals because, for example, the basic infinitesimal x does not have a square root.

The Levi-Civita field

The Levi-Civita field is similar to the Laurent series, but is algebraically closed. For example, the basic infinitesimal x has a square root. This field is rich enough to allow a significant amount of analysis to be done, but its elements can still be represented on a computer in the same sense that real numbers can be represented in floating point. It has applications to numerical differentiation in cases that are intractable by symbolic differentiation or finite-difference methods.[6]

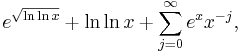

Transseries

The field of transseries is larger than the Levi-Civita field.[7] An example of a transseries is:

where for purposes of ordering x is considered to be infinite.

Surreal numbers

Conway's surreal numbers fall into category 2. They are a system that was designed to be as rich as possible in different sizes of numbers, but not necessarily for convenience in doing analysis. Certain transcendental functions can be carried over to the surreals, including logarithms and exponenentials, but most, e.g., the sine function, cannot. The existence of any particular surreal number, even one that has a direct counterpart in the reals, is not known a priori, and must be proved.

The hyperreal system

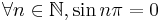

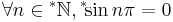

The most widespread technique for handling infinitesimals is the hyperreals, developed by Abraham Robinson in the 1960s. They fall into category 3 above, having been designed that way in order to allow all of classical analysis to be carried over from the reals. This property of being able to carry over all relations in a natural way is known as the transfer principle, proved by Jerzy Łoś in 1955. For example, the transcendental function sin has a natural counterpart *sin that takes a hyperreal input and gives a hyperreal output, and similarly the set of natural numbers  has a natural counterpart

has a natural counterpart  , which contains both finite and infinite integers. A proposition such as

, which contains both finite and infinite integers. A proposition such as  carries over to the hyperreals as

carries over to the hyperreals as  .

.

Superreals

The superreal number system of Dales and Woodin is a generalization of the hyperreals. It is different from the super-real system defined by David Tall.

Smooth infinitesimal analysis

Synthetic differential geometry or smooth infinitesimal analysis have roots in category theory. This approach departs from the classical logic used in conventional mathematics by denying the general applicability of the law of excluded middle — i.e., not (a ≠ b) does not have to mean a = b. A nilsquare or nilpotent infinitesimal can then be defined. This is a number x where x2 = 0 is true, but x = 0 need not be true at the same time. Since the background logic is intuitionistic logic, it is not immediately clear how to classify this system with regard to classes 1, 2, and 3. Intuitionistic analogues of these classes would have to be developed first.

Infinitesimal delta functions

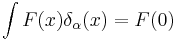

Cauchy used an infinitesimal  to write down a unit impulse, infinitely tall and narrow Dirac-type delta function

to write down a unit impulse, infinitely tall and narrow Dirac-type delta function  satisfying

satisfying  in a number of articles in 1827, see Laugwitz (1989). Cauchy defined an infinitesimal in 1821 (Cours d'Analyse) in terms of a sequence tending to zero. Namely, such a null sequence becomes an infinitesimal in Cauchy's and Lazare Carnot's terminology.

in a number of articles in 1827, see Laugwitz (1989). Cauchy defined an infinitesimal in 1821 (Cours d'Analyse) in terms of a sequence tending to zero. Namely, such a null sequence becomes an infinitesimal in Cauchy's and Lazare Carnot's terminology.

Modern set-theoretic approaches allow one to define infinitesimals via the ultrapower construction, where a null sequence becomes an infinitesimal in the sense of an equivalence class modulo a relation defined in terms of a suitable ultrafilter. The article by Yamashita (2007) contains a bibliography on modern Dirac delta functions in the context of an infinitesimal-enriched continuum provided by the hyperreals.

Logical properties

The method of constructing infinitesimals of the kind used in nonstandard analysis depends on the model and which collection of axioms are used. We consider here systems where infinitesimals can be shown to exist.

In 1936 Maltsev proved the compactness theorem. This theorem is fundamental for the existence of infinitesimals as it proves that it is possible to formalise them. A consequence of this theorem is that if there is a number system in which it is true that for any positive integer n there is a positive number x such that 0 < x < 1/n, then there exists an extension of that number system in which it is true that there exists a positive number x such that for any positive integer n we have 0 < x < 1/n. The possibility to switch "for any" and "there exists" is crucial. The first statement is true in the real numbers as given in ZFC set theory : for any positive integer n it is possible to find a real number between 1/n and zero, but this real number will depend on n. Here, one chooses n first, then one finds the corresponding x. In the second expression, the statement says that there is an x (at least one), chosen first, which is between 0 and 1/n for any n. In this case x is infinitesimal. This is not true in the real numbers (R) given by ZFC. Nonetheless, the theorem proves that there is a model (a number system) in which this will be true. The question is: what is this model? What are its properties? Is there only one such model?

There are in fact many ways to construct such a one-dimensional linearly ordered set of numbers, but fundamentally, there are two different approaches:

- 1) Extend the number system so that it contains more numbers than the real numbers.

- 2) Extend the axioms (or extend the language) so that the distinction between the infinitesimals and non-infinitesimals can be made in the real numbers themselves.

In 1960, Abraham Robinson provided an answer following the first approach. The extended set is called the hyperreals and contains numbers less in absolute value than any positive real number. The method may be considered relatively complex but it does prove that infinitesimals exist in the universe of ZFC set theory. The real numbers are called standard numbers and the new non-real hyperreals are called nonstandard.

In 1977 Edward Nelson provided an answer following the second approach. The extended axioms are IST, which stands either for Internal Set Theory or for the initials of the three extra axioms: Idealization, Standardization, Transfer. In this system we consider that the language is extended in such a way that we can express facts about infinitesimals. The real numbers are either standard or nonstandard. An infinitesimal is a nonstandard real number which is less, in absolute value, than any positive standard real number.

In 2006 Karel Hrbacek developed an extension of Nelson's approach in which the real numbers are stratified in (infinitely) many levels i.e., in the coarsest level there are no infinitesimals nor unlimited numbers. Infinitesimals are in a finer level and there are also infinitesimals with respect to this new level and so on.

See also

Notes

- ^ Netz, Reviel; Saito, Ken; Tchernetska, Natalie: A new reading of Method Proposition 14: preliminary evidence from the Archimedes palimpsest. I. SCIAMVS 2 (2001), 9–29.

- ^ Archimedes, The Method of Mechanical Theorems; see Archimedes Palimpsest

- ^ Shukla, Kripa Shankar (1984). "Use of Calculus in Hindu Mathematics". Indian Journal of History of Science 19: 95–104.

- ^ George Berkeley, The Analyst; or a discourse addressed to an infidel mathematician

- ^ "Infinitesimals in Modern Mathematics". Jonhoyle.com. http://www.jonhoyle.com/MAAseaway/Infinitesimals.html. Retrieved 2011-03-11.

- ^ Khodr Shamseddine, "Analysis on the Levi-Civia Field: A Brief Overview," http://www.uwec.edu/surepam/media/RS-Overview.pdf

- ^ G. A. Edgar, "Transseries for Beginners," http://www.math.ohio-state.edu/~edgar/preprints/trans_begin/

References

- B. Crowell, "Calculus" (2003)

- Ehrlich, P. (2006) The rise of non-Archimedean mathematics and the roots of a misconception. I. The emergence of non-Archimedean systems of magnitudes. Arch. Hist. Exact Sci. 60, no. 1, 1–121.

- J. Keisler, "Elementary Calculus" (2000) University of Wisconsin

- K. Stroyan "Foundations of Infinitesimal Calculus" (1993)

- Stroyan, K. D.; Luxemburg, W. A. J. Introduction to the theory of infinitesimals. Pure and Applied Mathematics, No. 72. Academic Press [Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Publishers], New York-London, 1976.

- Robert Goldblatt (1998) "Lectures on the hyperreals" Springer.

- "Nonstandard Methods and Applications in Mathematics" (2007) Lecture Notes in Logic 25, Association for Symbolic Logic.

- "The Strength of Nonstandard Analysis" (2007) Springer.

- Laugwitz, D. (1989). "Definite values of infinite sums: aspects of the foundations of infinitesimal analysis around 1820". Arch. Hist. Exact Sci. 39 (3): 195–245. doi:10.1007/BF00329867.

- Yamashita, H.: Comment on: "Pointwise analysis of scalar Fields: a nonstandard approach" [J. Math. Phys. 47 (2006), no. 9, 092301; 16 pp.]. J. Math. Phys. 48 (2007), no. 8, 084101, 1 page.

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

)

) )

) )

) )

) )

) )

) )

) )

) )

)