Dimension (vector space)

In mathematics, the dimension of a vector space V is the cardinality (i.e. the number of vectors) of a basis of V. It is sometimes called Hamel dimension or algebraic dimension to distinguish it from other types of dimension. This description depends on two fundamental facts: for every vector space there exists a basis (if one assumes the axiom of choice), and all bases of a vector space have equal cardinality (see dimension theorem for vector spaces); as a result the dimension of a vector space is uniquely defined. The dimension of the vector space V over the field F can be written as dimF(V) or as [V : F], read "dimension of V over F". When F can be inferred from context, often just dim(V) is written.

We say V is finite-dimensional if the dimension of V is finite.

Contents |

Examples

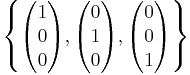

The vector space R3 has

as a basis, and therefore we have dimR(R3) = 3. More generally, dimR(Rn) = n, and even more generally, dimF(Fn) = n for any field F.

The complex numbers C are both a real and complex vector space; we have dimR(C) = 2 and dimC(C) = 1. So the dimension depends on the base field.

The only vector space with dimension 0 is {0}, the vector space consisting only of its zero element.

Facts

If W is a linear subspace of V, then dim(W) ≤ dim(V).

To show that two finite-dimensional vector spaces are equal, one often uses the following criterion: if V is a finite-dimensional vector space and W is a linear subspace of V with dim(W) = dim(V), then W = V.

Rn has the standard basis {e1, ..., en}, where ei is the i-th column of the corresponding identity matrix. Therefore Rn has dimension n.

Any two vector spaces over F having the same dimension are isomorphic. Any bijective map between their bases can be uniquely extended to a bijective linear map between the vector spaces. If B is some set, a vector space with dimension |B| over F can be constructed as follows: take the set F(B) of all functions f : B → F such that f(b) = 0 for all but finitely many b in B. These functions can be added and multiplied with elements of F, and we obtain the desired F-vector space.

An important result about dimensions is given by the rank-nullity theorem for linear maps.

If F/K is a field extension, then F is in particular a vector space over K. Furthermore, every F-vector space V is also a K-vector space. The dimensions are related by the formula

- dimK(V) = dimK(F) dimF(V).

In particular, every complex vector space of dimension n is a real vector space of dimension 2n.

Some simple formulae relate the dimension of a vector space with the cardinality of the base field and the cardinality of the space itself. If V is a vector space over a field F then, denoting the dimension of V by dimV, we have:

- If dim V is finite, then |V| = |F|dimV.

- If dim V is infinite, then |V| = max(|F|, dimV).

Generalizations

One can see a vector space as a particular case of a matroid, and in the latter there is a well-defined notion of dimension. The length of a module and the rank of an abelian group both have several properties similar to the dimension of vector spaces.

The Krull dimension of a commutative ring, named after Wolfgang Krull (1899–1971), is defined to be the maximal number of strict inclusions in an increasing chain of prime ideals in the ring.

Trace

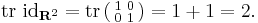

The dimension of a vector space may alternatively be characterized as the trace of the identity operator. For instance,  This begs the definition of trace, but allows useful generalizations.

This begs the definition of trace, but allows useful generalizations.

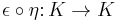

Firstly, it allows one to define a notion of dimension when one has a trace but no natural sense of basis. For example, one may have an algebra A with maps  (the inclusion of scalars, called the unit) and a map

(the inclusion of scalars, called the unit) and a map  (corresponding to trace, called the counit). The composition

(corresponding to trace, called the counit). The composition  is a scalar (being a linear operator on a 1-dimensional space) corresponds to "trace of identity", and gives a notion of dimension for an abstract algebra. In practice, in bialgebras one requires that this map be the identity, which can be obtained by normalizing the counit by dividing by dimension (

is a scalar (being a linear operator on a 1-dimensional space) corresponds to "trace of identity", and gives a notion of dimension for an abstract algebra. In practice, in bialgebras one requires that this map be the identity, which can be obtained by normalizing the counit by dividing by dimension ( ), so in these cases the normalizing constant corresponds to dimension.

), so in these cases the normalizing constant corresponds to dimension.

Alternatively, one may be able to take the trace of operators on an infinite-dimensional space; in this case a (finite) trace is defined, even though no (finite) dimension exists, and gives a notion of "dimension of the operator". These fall under the rubric of "trace class operators" on a Hilbert space, or more generally nuclear operators on a Banach space.

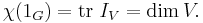

A subtler generalization is to consider the trace of a family of operators as a kind of "twisted" dimension. This occurs significantly in representation theory, where the character of a representation is the trace of the representation, hence a scalar-valued function on a group  whose value on the identity

whose value on the identity  is the dimension of the representation, as a representation sends the identity in the group to the identity matrix:

is the dimension of the representation, as a representation sends the identity in the group to the identity matrix:  One can view the other values

One can view the other values  of the character as "twisted" dimensions, and find analogs or generalizations of statements about dimensions to statements about characters or representations. A sophisticated example of this occurs in the theory of monstrous moonshine: the j-invariant is the graded dimension of an infinite-dimensional graded representation of the Monster group, and replacing the dimension with the character gives the McKay–Thompson series for each element of the Monster group.[1]

of the character as "twisted" dimensions, and find analogs or generalizations of statements about dimensions to statements about characters or representations. A sophisticated example of this occurs in the theory of monstrous moonshine: the j-invariant is the graded dimension of an infinite-dimensional graded representation of the Monster group, and replacing the dimension with the character gives the McKay–Thompson series for each element of the Monster group.[1]

See also

- Basis (linear algebra)

- Topological dimension, also called Lebesgue covering dimension

- Fractal dimension, also called Hausdorff dimension

- Krull dimension

References

- ^ (Gannon 2006)

- Gannon, Terry (2006), Moonshine beyond the Monster: The Bridge Connecting Algebra, Modular Forms and Physics, ISBN 0-521-83531-3

External links

- MIT Linear Algebra Lecture on Independence, Basis, and Dimension by Gilbert Strang at MIT OpenCourseWare