Independence Party (Iceland)

| Independence Party Sjálfstæðisflokkurinn |

|

|---|---|

| Chairman | Bjarni Benediktsson |

| Vice chairperson | Ólöf Nordal |

| Founded | 25 May 1929 |

| Headquarters | Háaleitisbraut 1 105 Reykjavík |

| Ideology | Liberal conservatism, Classical liberalism, Euroscepticism |

| Political position | Fiscal: Centre-right Social: Centre-right |

| International affiliation | International Democrat Union |

| European affiliation | Alliance of European Conservatives and Reformists |

| Official colours | Blue |

| Seats in the Althing |

16 / 63

|

| Website | |

| xd.is | |

| Politics of Iceland Political parties Elections |

|

The Independence Party (Icelandic: Sjálfstæðisflokkurinn) is a centre-right political party in Iceland.[1][2] Liberal conservative and Eurosceptic,[3][4] it is the second-largest party in the Althing, with sixteen seats. The chairman of the party is Bjarni Benediktsson and vice chairman is Ólöf Nordal.

It was formed in 1929 through a merger of the Conservative Party and the Liberal Party. This united the two parties advocating Icelandic independence, which was achieved in 1944. From 1929, the party was the largest party in the country until the 2009 election, when it fell behind the Social Democratic Alliance. Since the 2009 elections opinion polls have indicated that the party has regained its former position as the largest party. Until Benediktsson took the leadership after the 2009 defeat, every Independence Party leader has also held the office of Prime Minister.

Pragmatic rather than ideological,[5] the Independence Party broadly encompasses all centre-right thought in Iceland. Economically liberal and opposed to interventionism, the party is supported most strongly by fishermen, high-earners, and the well-educated,[6] particularly in Reykjavík.[5] It is less socially conservative than its Scandinavian counterparts.[5] It supports Icelandic membership of NATO and is the party most opposed to joining the European Union. It is a member of the International Democrat Union and the Alliance of European Conservatives and Reformists.

Contents |

History

The Independence Party was founded on 25 May 1929 through a merger of the Conservative Party and the Liberal Party. It readopted the name of the Old Independence Party, which had split between the Conservatives and Liberals in 1927.[7] From its first election, in 1931, it was the largest party in Iceland.[8]

The Independence Party won the 2007 elections, increasing their seat tally in the Althing by 3. It formed a new coalition government under Haarde with the Social Democratic Alliance, after their current coalition partner, the Progressive Party, lost heavily in the elections.

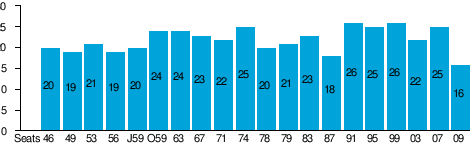

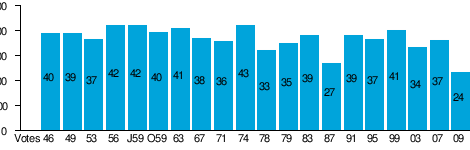

In the 2009 elections, the Independence Party dropped from 25–26 to 16 seats in the Althing, becoming Iceland's second-largest party following the Social Democratic Alliance (which gained two seats, to 20.)

Ideology

The party has been the sole major right-wing party in Iceland since its inception, and has captured a broad cross-section of centre-right voters. As a result, the party is not as far to the right as most right-wing parties in Scandinavia, serving as a 'catch-all' party,[9] similar to the British Conservative Party.[10] The party, like the British Conservatives, is primarily 'pragmatic', as opposed to ideological,[5][6][11] and its name is seen as an allusion to being independent of dogma.[12] For most of its period of political dominance, the party has relied upon coalition government, and has made coalitions with all major parties in parliament.[10]

The Independence Party has generally been economically liberal and advocated limited government intervention in the economy.[6] It was originally committed to laissez-faire economics, but shifted its economy left-wards in the 1930s, accepting the creation of a welfare state.[5]

The party has been less conservative on social issues than centre-right parties in Scandinavia.[5] The party was the only consistent advocate for the end of prohibition of beer, and provided three-quarters of voters in favour of legalisation; the ban was lifted in 1989.[13]

Of all Iceland's parties, the Indepencence Party is the most opposed to membership of the European Union. The party's position on EU membership was confirmed at its national congress on March 2009.[14] Its near-permanent position as Iceland's largest party has guaranteed Iceland's Atlanticist stance.[15] The party is in favour of allowing Icelanders to participate in peacekeeping missions, including in Afghanistan.[16]

Political support

| Iceland |

This article is part of the series: |

|

|

|

Constitution

Institutions

Foreign Affairs

|

|

Other countries · Atlas |

The party is the most successful right-wing party in the Nordic countries.[9] It has a broad base of support, but is most strongly supported by Iceland's large fishing community and by businesses.[6] On the biggest divide in Icelandic politics, between urban and rural areas, the Independence Party is firmly supported by the urban population,[6] mostly found in Reykjavík.[5]

The Independence Party has always attempted to avoid appealing to a social class, and Iceland has never developed a political cleavage based on class.[17] As such, the party is relatively successful at attracting working class voters,[10] which partly comes from the party's strong advocacy of independence in the 1930s.[18] However, most of its strength is in the middle class,[13][19] and the party is disproportionately supported by those on high incomes and those with university educations.[6]

The party has long been endorsed by Morgunblaðið,[13] the Icelandic newspaper of record.[20] Davíð Oddsson, the longest-serving Prime Minister, is one of two editors of the paper. The paper was also historically supported by the afternoon newspaper Visir, now part of DV.[5]

Organisation

The party has a tradition of individualism and strong personalities, which has proven difficult for the leadership to manage. The Commonwealth Party split in 1941, while the Republican Party left in 1953: both in opposition to the left-wards shift of the party away from classical liberalism.[5] The Citizens' Party split from the party in 1983, but collapsed in 1994.[11]

The Reykjavík youth branch is called Heimdallur.

The party has a very large membership base, with 10% of the population being a member of the party.[21]

Election results

|

|

Leaders

All former chairmen of the party have held the office of the Prime Minister of Iceland: Ólafur Thors, Bjarni Benediktsson, Jóhann Hafstein, Geir Hallgrímsson, Þorsteinn Pálsson, Davíð Oddsson and Geir H. Haarde. Jón Þorláksson, the first chairman of the Independence party was Prime Minister for the Conservative party prior to the foundation of the Independence party. Gunnar Thoroddsen, who was the party's vice chairman 1974–1981, was Iceland's PM from 1980 to 1983, but the Independence Party did not officially support his government, although some MPs in the party did.

| Leader | From | To | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | Jón Þorláksson | 29 May 1929 | 2 October 1934 |

| 2nd | Ólafur Thors | 2 October 1934 | 22 October 1961 |

| 3rd | Bjarni Benediktsson | 22 October 1961 | 10 July 1970 |

| 4th | Jóhann Hafstein | 10 July 1970 | 12 October 1973 |

| 5th | Geir Hallgrímsson | 12 October 1973 | 6 November 1983 |

| 6th | Þorsteinn Pálsson | 6 November 1983 | 10 March 1991 |

| 7th | Davíð Oddsson | 10 March 1991 | 16 October 2005 |

| 8th | Geir Haarde | 16 October 2005 | 29 March 2009 |

| 9th | Bjarni Benediktsson | 29 March 2009 | Present |

Footnotes

- ^ "Centre-left wins Iceland election". BBC News. 26 April 2009. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/8017927.stm.

- ^ Waterfield, Bruno (26 April 2009). "Iceland elects new Left-wing government". The Daily Telegraph. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/iceland/5226431/Iceland-elects-new-Left-wing-government.html.

- ^ Steed, Michael (1988). "Identifying Liberal Parties". In Kirchner, Emil Joseph. Liberal Parties in Western Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 376–95. ISBN 978-0-52132-394-9.

- ^ Nergelius, Joakim (2006). Nordic and other European constitutional traditions. Leiden: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 34. ISBN 9789004151710.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Tomasson (1980), p. 42

- ^ a b c d e f Siaroff, Alan (2000). Comparative European party systems: an analysis of parliamentary elections. London: Taylor & Francis. p. 295. ISBN 9780815329305.

- ^ McHale, Vincent E.; Skowronski, Sharon (1983). Political Parties of Europe: Albania-Norway. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. p. 522. ISBN 9780313238048.

- ^ Tomasson (1980), p. 41–2

- ^ a b Hansen, Erik Jørgen (2006). Welfare trends in the Scandinavian countries, Part 2. New York: M. E. Sharpe. p. 81. ISBN 9780873328449.

- ^ a b c Arter, David (2006). Democracy in Scandinavia. Manchester: Manchester University Press. p. 50. ISBN 9780719070471.

- ^ a b Cross, William (2007). Democratic reform in New Brunswick. Toronto: Canadian Scholars' Press. pp. 68–9. ISBN 9781551303260.

- ^ Woods, Leigh; Gunnarsdóttir, Ágústa (1997). Public Selves and Political Stages. London: Routledge. p. 10. ISBN 9783718658732.

- ^ a b c Gunnlaugsson, Helgi; Galliher, John F. (2000). Wayward Icelanders. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. p. 39. ISBN 9780299165345.

- ^ "Ályktun um Evrópumál samþykkt". http://www.xd.is/?action=grein&id=18403

- ^ Bailes, Alyson J. K.; Herolf, Gunilla; Sundelius, Bengt (2006). The Nordic countries and the European Security and Defence Policy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 329. ISBN 9780199290840.

- ^ Malley-Morrison, Kathleen (2009). State Violence and the Right to Peace. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. p. 92. ISBN 9780275996512.

- ^ Jónsson, Ásgeir (2009). Why Iceland?. New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 140. ISBN 9780071632843.

- ^ Arter, David (1999). Scandinavian politics today. Manchester: Manchester University Press. p. 91. ISBN 9780719051333.

- ^ Gill, Derek; Ingman, Stanley R. (1994). Eldercare, distributive justice, and the welfare state. Albany: State University of New York Press. p. 90. ISBN 9780791417652.

- ^ Pálsson, Gísli (2007). Anthropology and the new genetics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 132. ISBN 9780521671743.

- ^ Jacobs, Francis (1989). Western European political parties. London: Longman. p. 551. ISBN 9780582001138.

References

- Tomasson, Richard F. (1980). Iceland: The First New Society. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 9780816609130.

External links

- Official website (English)

- The National Youth Organisation of the Independence Party, named Samband ungra sjálfstæðismanna or SUS in Icelandic, is one of the oldest political youth movements in Iceland. Its chairman is Ólafur Örn Nielsen.

- About the Independence Party

|

|||||||||||

|

||||||||