Ideal gas law

The ideal gas law is the equation of state of a hypothetical ideal gas. It is a good approximation to the behavior of many gases under many conditions, although it has several limitations. It was first stated by Émile Clapeyron in 1834 as a combination of Boyle's law and Charles's law.[1] It can also be derived from kinetic theory, as was achieved (apparently independently) by August Krönig in 1856[2] and Rudolf Clausius in 1857.[3]

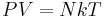

The state of an amount of gas is determined by its pressure, volume, and temperature. The modern form of the equation is:

where P is the absolute pressure of the gas measured in atmospheres; V is the volume (in this equation the volume is expressed in liters); N is the number of particles in the gas; k is Boltzmann's constant relating temperature and energy; and T is the absolute temperature.

In SI units, P is measured in pascals; V in cubic metres; N is a dimensionless number; and T in kelvin. k has the value 1.38·10−23 J·K−1 in SI units.

Sometimes this is expressed as

where n is the amount of substance of gas (also known as number of moles) and R is the ideal, or universal, gas constant, equal to the product of Boltzmann's constant and Avogadro's constant. In SI units, n is measured in moles, and T in kelvin. R has the value 8.314 J·K−1·mol−1.

The temperature used in the equation of state is an absolute temperature: in the SI system of units, kelvins; in the Imperial system, degrees Rankine.[4]

Contents |

Deviations from real gases

The equation of state given here applies only to an ideal gas, or as an approximation to a real gas that behaves sufficiently like an ideal gas. There are in fact many different forms of the equation of state for different gases. Since it neglects both molecular size and intermolecular attractions, the ideal gas law is most accurate for monatomic gases at high temperatures and low pressures. The neglect of molecular size becomes less important for lower densities, i.e. for larger volumes at lower pressures, because the average distance between adjacent molecules becomes much larger than the molecular size. The relative importance of intermolecular attractions diminishes with increasing thermal kinetic energy, i.e., with increasing temperatures. More detailed equations of state, such as the van der Waals equation, allow deviations from ideality caused by molecular size and intermolecular forces to be taken into account.

A residual property is defined as the difference between a real gas property and an ideal gas property, both considered at the same pressure, temperature, and composition.

Alternative forms

Molar form

As the amount of substance could be given in mass instead of moles, sometimes an alternative form of the ideal gas law is useful. The number of moles (n) is equal to the mass (m) divided by the molar mass (M):

By replacing n, with density ρ = m/V, we get:

Defining the specific gas constant Rspecific as the ratio R/M,

This form of the ideal gas law is very useful because it links pressure, density, and temperature in a unique formula independent of the quantity of the considered gas. Alternatively, the law may be written in terms of the specific volume v, the reciprocal of density, as

It is common, especially in engineering applications, to represent the specific gas constant by the symbol R. In such cases, the universal gas constant is usually given a different symbol such as R to distinguish it. In any case, the context and/or units of the gas constant should make it clear as to whether the universal or specific gas constant is being referred to.[5]

Statistical mechanics

In statistical mechanics the following molecular equation is derived from first principles:

Here k is the Boltzmann constant, and N is the actual number of molecules, in contrast to the other formulation, which uses n, the number of moles. This relation implies that Nk = nR, and the consistency of this result with experiment is a good check on the principles of statistical mechanics.

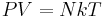

From here we can notice that for an average particle mass of μ times the atomic mass constant mu (i.e., the mass is μ u)

and since ρ = m/V, we find that the ideal gas law can be rewritten as:

Applications to thermodynamic processes

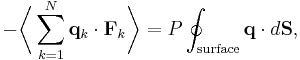

The table below essentially simplifies the ideal gas equation for a particular processes, thus making this equation easier to solve using numerical methods.

A thermodynamic process is defined as a system that moves from state 1 to state 2, where the state number is denoted by subscript. As shown in the first column of the table, basic thermodynamic processes are defined such that one of the gas properties (P, V, T, or S) is constant throughout the process.

For a given thermodynamics process, in order to specify the extent of a particular process, one of the properties ratios (listed under the column labeled "known ratio") must be specified (either directly or indirectly). Also, the property for which the ratio is known must be distinct from the property held constant in the previous column (otherwise the ratio would be unity, and not enough information would be available to simplify the gas law equation).

In the final three columns, the properties (P, V, or T) at state 2 can be calculated from the properties at state 1 using the equations listed.

| Process | Constant | Known ratio | P2 | V2 | T2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isobaric process |

|

|

P2 = P1 | V2 = V1(V2/V1) | T2 = T1(V2/V1) |

|

|

P2 = P1 | V2 = V1(T2/T1) | T2 = T1(T2/T1) | ||

| Isochoric process |

|

|

P2 = P1(P2/P1) | V2 = V1 | T2 = T1(P2/P1) |

|

|

P2 = P1(T2/T1) | V2 = V1 | T2 = T1(T2/T1) | ||

| Isothermal process |

|

|

P2 = P1(P2/P1) | V2 = V1/(P2/P1) | T2 = T1 |

|

|

P2 = P1/(V2/V1) | V2 = V1(V2/V1) | T2 = T1 | ||

| Isentropic process (Reversible adiabatic process) |

|

|

P2 = P1(P2/P1) | V2 = V1(P2/P1)(−1/γ) | T2 = T1(P2/P1)(1 − 1/γ) |

|

|

P2 = P1(V2/V1)−γ | V2 = V1(V2/V1) | T2 = T1(V2/V1)(1 − γ) | ||

|

|

P2 = P1(T2/T1)γ/(γ − 1) | V2 = V1(T2/T1)1/(1 − γ) | T2 = T1(T2/T1) | ||

| Polytropic process |

|

|

P2 = P1(P2/P1) | V2 = V1(P2/P1)(-1/n) | T2 = T1(P2/P1)(1 - 1/n) |

|

|

P2 = P1(V2/V1)−n | V2 = V1(V2/V1) | T2 = T1(V2/V1)(1−n) | ||

|

|

P2 = P1(T2/T1)n/(n − 1) | V2 = V1(T2/T1)1/(1 − n) | T2 = T1(T2/T1) |

^ a. In an isentropic process, system entropy (S) is constant. Under these conditions, P1 V1γ = P2 V2γ, where γ is defined as the heat capacity ratio, which is constant for an ideal gas. The value used for γ is typically 1.4 for diatomic gases like nitrogen (N2) and oxygen (O2), (and air, which is 99% diatomic). Also γ is typically 1.6 for monatomic gases like the noble gases helium (He), and argon (Ar). In internal combustion engines γ varies between 1.35 and 1.15, depending on constitution gases and temperature.

Derivations

Empirical

The ideal gas law can be derived from combining two empirical gas laws: the combined gas law and Avogadro's law. The combined gas law states that

where C is a constant which is directly proportional to the amount of gas, n (Avogadro's law). The proportionality factor is the universal gas constant, R, i.e. C = nR.

Hence the ideal gas law

Theoretical

The ideal gas law can also be derived from first principles using the kinetic theory of gases, in which several simplifying assumptions are made, chief among which are that the molecules, or atoms, of the gas are point masses, possessing mass but no significant volume, and undergo only elastic collisions with each other and the sides of the container in which both linear momentum and kinetic energy are conserved.

From statistical mechanics

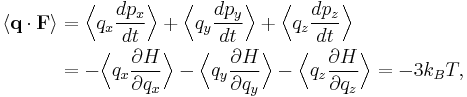

Let q = (qx, qy, qz) and p = (px, py, pz) denote the position vector and momentum vector of a particle of an ideal gas, respectively. Let F denote the net force on that particle. Then the time average momentum of the particle is:

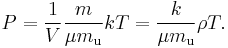

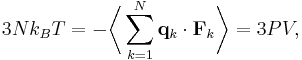

where the first equality is Newton's second law, and the second line uses Hamilton's equations and the equipartition theorem. Summing over a system of N particles yields

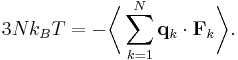

By Newton's third law and the ideal gas assumption, the net force on the system is the force applied by the walls of their container, and this force is given by the pressure P of the gas. Hence

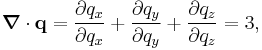

where dS is the infinitesimal area element along the walls of the container. Since the divergence of the position vector q is

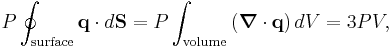

the divergence theorem implies that

where dV is an infinitesimal volume within the container and V is the total volume of the container.

Putting these equalities together yields

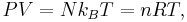

which immediately implies the ideal gas law for N particles:

where n = N/NA is the number of moles of gas and R = NAkB is the gas constant.

The readers are referred to the comprehensive article Configuration integral (statistical mechanics) where an alternative statistical mechanics derivation of the ideal-gas law, using the relationship between the Helmholtz free energy and the partition function, but without using the equipartition theorem, is provided.

See also

- Combined gas law

- Van der Waals equation

- Boltzmann's constant

- Configuration integral

- Dynamic pressure

References

- ^ Clapeyron, E. (1834). "Mémoire sur la puissance motrice de la chaleur". Journal de l'École Polytechnique XIV: 153–90. (French) Facsimile at the Bibliothèque nationale de France (pp. 153–90).

- ^ Krönig, A. (1856). "Grundzüge einer Theorie der Gase". Annalen der Physik 99 (10): 315–22. Bibcode 1856AnP...175..315K. doi:10.1002/andp.18561751008. (German) Facsimile at the Bibliothèque nationale de France (pp. 315–22).

- ^ Clausius, R. (1857). "Ueber die Art der Bewegung, welche wir Wärme nennen". Annalen der Physik und Chemie 176 (3): 353–79. Bibcode 1857AnP...176..353C. doi:10.1002/andp.18571760302. (German) Facsimile at the Bibliothèque nationale de France (pp. 353–79).

- ^ "Equation of State". http://www.grc.nasa.gov/WWW/K-12/airplane/eqstat.html.

- ^ Moran and Shapiro, Fundamentals of Engineering Thermodynamics, Wiley, 4th Ed, 2000

Further reading

- Davis and Masten Principles of Environmental Engineering and Science, McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. New York (2002) ISBN 0-07-235053-9

- Website giving credit to Benoît Paul Émile Clapeyron, (1799–1864) in 1834

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||