Heat engine

In thermodynamics, a heat engine is a system that performs the conversion of heat or thermal energy to mechanical work.[1][2] It does this by bringing a working substance from a high temperature state to a lower temperature state. A heat "source" generates thermal energy that brings the working substance to the high temperature state. The working substance generates work in the "working body" of the engine while transferring heat to the colder "sink" until it reaches a low temperature state. During this process some of the thermal energy is converted into work by exploiting the properties of the working substance. The working substance can be any system with a non-zero heat capacity, but it usually is a gas or liquid.

In general an engine converts energy to mechanical work. Heat engines distinguish themselves from other types of engines by the fact that their efficiency is fundamentally limited by Carnot's theorem.[3] Although this efficiency limitation can be a drawback, an advantage of heat engines is that most forms of energy can be easily converted to heat by processes like exothermic reactions (such as combustion), absorption of light or energetic particles, friction, dissipation and resistance. Since the heat source that supplies thermal energy to the engine can thus be powered by virtually any kind of energy, heat engines are very versatile and have a wide range of applicability.

Heat engines are often confused with the cycles they attempt to mimic. Typically when describing the physical device the term 'engine' is used. When describing the model the term 'cycle' is used.

Contents |

Overview

In thermodynamics, heat engines are often modeled using a standard engineering model such as the Otto cycle. The theoretical model can be refined and augmented with actual data from an operating engine, using tools such as an indicator diagram. Since very few actual implementations of heat engines exactly match their underlying thermodynamic cycles, one could say that a thermodynamic cycle is an ideal case of a mechanical engine. In any case, fully understanding an engine and its efficiency requires gaining a good understanding of the (possibly simplified or idealized) theoretical model, the practical nuances of an actual mechanical engine, and the discrepancies between the two.

In general terms, the larger the difference in temperature between the hot source and the cold sink, the larger is the potential thermal efficiency of the cycle. On Earth, the cold side of any heat engine is limited to being close to the ambient temperature of the environment, or not much lower than 300 Kelvin, so most efforts to improve the thermodynamic efficiencies of various heat engines focus on increasing the temperature of the source, within material limits. The maximum theoretical efficiency of a heat engine (which no engine ever obtains) is equal to the temperature difference between the hot and cold ends divided by the temperature at the hot end, all expressed in absolute temperature or kelvins.

The efficiency of various heat engines proposed or used today ranges from 3 percent (97 percent waste heat) for the OTEC ocean power proposal through 25 percent for most automotive engines , to 45 percent for a supercritical coal-fired power station, to about 60 percent for a steam-cooled combined cycle gas turbine.[4]

All of these processes gain their efficiency (or lack thereof) due to the temperature drop across them.

Power

Heat engines can be characterized by their specific power, which is typically given in kilowatts per litre of engine displacement (in the U.S. also horsepower per cubic inch). The result offers an approximation of the peak-power output of an engine. This is not to be confused with fuel efficiency, since high-efficiency often requires a lean fuel-air ratio, and thus lower power density. A modern high-performance car engine makes in excess of 75 kW/L (1.65 hp/in³).

Everyday examples

Examples of everyday heat engines include the steam engine, the diesel engine, and the gasoline (petrol) engine in an automobile. A common toy that is also a heat engine is a drinking bird. Also the stirling engine is a heat engine. All of these familiar heat engines are powered by the expansion of heated gases. The general surroundings are the heat sink, providing relatively cool gases which, when heated, expand rapidly to drive the mechanical motion of the engine.

Examples of heat engines

It is important to note that although some cycles have a typical combustion location (internal or external), they often can be implemented with the other. For example, John Ericsson developed an external heated engine running on a cycle very much like the earlier Diesel cycle. In addition, the externally heated engines can often be implemented in open or closed cycles.

What this boils down to is that there are thermodynamic cycles and a large number of ways to implement them.

Phase change cycles

In these cycles and engines, the working fluids are gases and liquids. The engine converts the working fluid from a gas to a liquid, from liquid to gas, or both, generating work from the fluid expansion or compression.

- Rankine cycle (classical steam engine)

- Regenerative cycle (steam engine more efficient than Rankine cycle)

- Organic Rankine cycle (Coolant changing phase in temperature ranges of ice and hot liquid water)

- Vapor to liquid cycle (Drinking bird, Injector, Minto wheel)

- Liquid to solid cycle (Frost heaving — water changing from ice to liquid and back again can lift rock up to 60 cm.)

- Solid to gas cycle (Dry ice cannon — Dry ice sublimes to gas.)

Gas only cycles

In these cycles and engines the working fluid is always a gas (i.e., there is no phase change):

- Carnot cycle (Carnot heat engine)

- Ericsson Cycle (Caloric Ship John Ericsson)

- Stirling cycle (Stirling engine, thermoacoustic devices)

- Internal combustion engine (ICE):

- Otto cycle (e.g. Gasoline/Petrol engine, high-speed diesel engine)

- Diesel cycle (e.g. low-speed diesel engine)

- Atkinson Cycle (Atkinson Engine)

- Brayton cycle or Joule cycle originally Ericsson Cycle (gas turbine)

- Lenoir cycle (e.g., pulse jet engine)

- Miller cycle

Liquid only cycles

In these cycles and engines the working fluid are always like liquid:

- Stirling Cycle (Malone engine)

- Heat Regenerative Cyclone [5]

Electron cycles

- Johnson thermoelectric energy converter

- Thermoelectric (Peltier-Seebeck effect)

- Thermionic emission

- Thermotunnel cooling

Magnetic cycles

- Thermo-magnetic motor (Tesla)

Cycles used for refrigeration

A domestic refrigerator is an example of a heat pump: a heat engine in reverse. Work is used to create a heat differential. Many cycles can run in reverse to move heat from the cold side to the hot side, making the cold side cooler and the hot side hotter. Internal combustion engine versions of these cycles are, by their nature, not reversible.

Refrigeration cycles include:

- Vapor-compression refrigeration

- Stirling cryocoolers

- Gas-absorption refrigerator

- Air cycle machine

- Vuilleumier refrigeration

- Magnetic refrigeration

Evaporative Heat Engines

The Barton evaporation engine is a heat engine based on a cycle producing power and cooled moist air from the evaporation of water into hot dry air.

Mesoscopic Heat Engines

Mesoscopic heat engines are nanoscale devices that may serve the goal of processing heat fluxes and perform useful work at small scales. Potential applications include e.g. electric cooling devices. In such mesoscopic heat engines, work per cycle of operation fluctuates due to thermal noise. There is exact equality that relates average of exponents of work performed by any heat engine and the heat transfer from the hotter heat bath [6] . This relation transforms the Carnot's inequality into exact equality.

Efficiency

The efficiency of a heat engine relates how much useful work is output for a given amount of heat energy input.

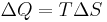

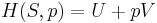

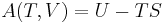

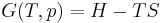

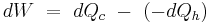

From the laws of thermodynamics:

-

- where

is the work extracted from the engine. (It is negative since work is done by the engine.)

is the work extracted from the engine. (It is negative since work is done by the engine.) is the heat energy taken from the high temperature system. (It is negative since heat is extracted from the source, hence

is the heat energy taken from the high temperature system. (It is negative since heat is extracted from the source, hence  is positive.)

is positive.) is the heat energy delivered to the cold temperature system. (It is positive since heat is added to the sink.)

is the heat energy delivered to the cold temperature system. (It is positive since heat is added to the sink.)

In other words, a heat engine absorbs heat energy from the high temperature heat source, converting part of it to useful work and delivering the rest to the cold temperature heat sink.

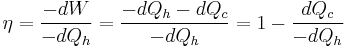

In general, the efficiency of a given heat transfer process (whether it be a refrigerator, a heat pump or an engine) is defined informally by the ratio of "what you get out" to "what you put in."

In the case of an engine, one desires to extract work and puts in a heat transfer.

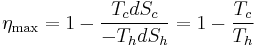

The theoretical maximum efficiency of any heat engine depends only on the temperatures it operates between. This efficiency is usually derived using an ideal imaginary heat engine such as the Carnot heat engine, although other engines using different cycles can also attain maximum efficiency. Mathematically, this is because in reversible processes, the change in entropy of the cold reservoir is the negative of that of the hot reservoir (i.e.,  ), keeping the overall change of entropy zero. Thus:

), keeping the overall change of entropy zero. Thus:

where  is the absolute temperature of the hot source and

is the absolute temperature of the hot source and  that of the cold sink, usually measured in kelvin. Note that

that of the cold sink, usually measured in kelvin. Note that  is positive while

is positive while  is negative; in any reversible work-extracting process, entropy is overall not increased, but rather is moved from a hot (high-entropy) system to a cold (low-entropy one), decreasing the entropy of the heat source and increasing that of the heat sink.

is negative; in any reversible work-extracting process, entropy is overall not increased, but rather is moved from a hot (high-entropy) system to a cold (low-entropy one), decreasing the entropy of the heat source and increasing that of the heat sink.

The reasoning behind this being the maximal efficiency goes as follows. It is first assumed that if a more efficient heat engine than a Carnot engine is possible, then it could be driven in reverse as a heat pump. Mathematical analysis can be used to show that this assumed combination would result in a net decrease in entropy. Since, by the second law of thermodynamics, this is statistically improbable to the point of exclusion, the Carnot efficiency is a theoretical upper bound on the reliable efficiency of any process.

Empirically, no engine has ever been shown to run at a greater efficiency than a Carnot cycle heat engine.

Figure 2 and Figure 3 show variations on Carnot cycle efficiency. Figure 2 indicates how efficiency changes with an increase in the heat addition temperature for a constant compressor inlet temperature. Figure 3 indicates how the efficiency changes with an increase in the heat rejection temperature for a constant turbine inlet temperature.

Endoreversible heat engines

The most Carnot efficiency as a criterion of heat engine performance is the fact that by its nature, any maximally efficient Carnot cycle must operate at an infinitesimal temperature gradient. This is because any transfer of heat between two bodies at differing temperatures is irreversible, and therefore the Carnot efficiency expression only applies in the infinitesimal limit. The major problem with that is that the object of most heat engines is to output some sort of power, and infinitesimal power is usually not what is being sought.

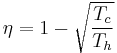

A different measure of ideal heat engine efficiency is given by considerations of endoreversible thermodynamics, where the cycle is identical to the Carnot cycle except in that the two processes of heat transfer are not reversible (Callen 1985):

This model does a better job of predicting how well real-world heat engines can do (Callen 1985, see also endoreversible thermodynamics):

| Power station |  (°C) (°C) |

(°C) (°C) |

(Carnot) (Carnot) |

(Endoreversible) (Endoreversible) |

(Observed) (Observed) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| West Thurrock (UK) coal-fired power station | 25 | 565 | 0.64 | 0.40 | 0.36 |

| CANDU (Canada) nuclear power station | 25 | 300 | 0.48 | 0.28 | 0.30 |

| Larderello (Italy) geothermal power station | 80 | 250 | 0.33 | 0.178 | 0.16 |

As shown, the endoreversible efficiency much more closely models the observed data.

History

Heat engines have been known since antiquity but were only made into useful devices at the time of the industrial revolution in the eighteenth century. They continue to be developed today.

Heat engine enhancements

Engineers have studied the various heat engine cycles extensively in an effort to improve the amount of usable work they could extract from a given power source. The Carnot Cycle limit cannot be reached with any gas-based cycle, but engineers have worked out at least two ways to possibly go around that limit, and one way to get better efficiency without bending any rules.

- Increase the temperature difference in the heat engine. The simplest way to do this is to increase the hot side temperature, which is the approach used in modern combined-cycle gas turbines. Unfortunately, physical limits (such as the melting point of the materials from which the engine is constructed) and environmental concerns regarding NOx production restrict the maximum temperature on workable heat engines. Modern gas turbines run at temperatures as high as possible within the range of temperatures necessary to maintain acceptable NOx output . Another way of increasing efficiency is to lower the output temperature. One new method of doing so is to use mixed chemical working fluids, and then exploit the changing behavior of the mixtures. One of the most famous is the so-called Kalina cycle, which uses a 70/30 mix of ammonia and water as its working fluid. This mixture allows the cycle to generate useful power at considerably lower temperatures than most other processes.

- Exploit the physical properties of the working fluid. The most common such exploitation is the use of water above the so-called critical point, or so-called supercritical steam. The behavior of fluids above their critical point changes radically, and with materials such as water and carbon dioxide it is possible to exploit those changes in behavior to extract greater thermodynamic efficiency from the heat engine, even if it is using a fairly conventional Brayton or Rankine cycle. A newer and very promising material for such applications is CO2. SO2 and xenon have also been considered for such applications, although SO2 is a little toxic for most.

- Exploit the chemical properties of the working fluid. A fairly new and novel exploit is to use exotic working fluids with advantageous chemical properties. One such is nitrogen dioxide (NO2), a toxic component of smog, which has a natural dimer as di-nitrogen tetraoxide (N2O4). At low temperature, the N2O4 is compressed and then heated. The increasing temperature causes each N2O4 to break apart into two NO2 molecules. This lowers the molecular weight of the working fluid, which drastically increases the efficiency of the cycle. Once the NO2 has expanded through the turbine, it is cooled by the heat sink, which causes it to recombine into N2O4. This is then fed back to the compressor for another cycle. Such species as aluminium bromide (Al2Br6), NOCl, and Ga2I6 have all been investigated for such uses. To date, their drawbacks have not warranted their use, despite the efficiency gains that can be realized.[7]

Heat engine processes

| Cycle | Process 1-2 (Compression) |

Process 2-3 (Heat Addition) |

Process 3-4 (Expansion) |

Process 4-1 (Heat Rejection) |

Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Power cycles normally with external combustion - or heat pump cycles: | |||||

| Bell Coleman | adiabatic | isobaric | adiabatic | isobaric | A reversed Brayton cycle |

| Carnot | isentropic | isothermal | isentropic | isothermal | |

| Ericsson | isothermal | isobaric | isothermal | isobaric | the second Ericsson cycle from 1853 |

| Scuderi | adiabatic | variable pressure and volume |

adiabatic | isochoric | |

| Stirling | isothermal | isochoric | isothermal | isochoric | |

| Stoddard | adiabatic | isobaric | adiabatic | isobaric | |

Power cycles normally with internal combustion: |

|||||

| Brayton | adiabatic | isobaric | adiabatic | isobaric | Jet engines the external combustion version of this cycle is known as first Ericsson cycle from 1833 |

| Diesel | adiabatic | isobaric | adiabatic | isochoric | |

| Lenoir | isobaric | isochoric | adiabatic | Pulse jets (Note: Process 1-2 accomplishes both the heat rejection and the compression) |

|

| Otto | adiabatic | isochoric | adiabatic | isochoric | Gasoline / petrol engines |

| Rankine | adiabatic | isobaric | adiabatic | isobaric | Steam engine |

Each process is one of the following:

- isothermal (at constant temperature, maintained with heat added or removed from a heat source or sink)

- isobaric (at constant pressure)

- isometric/isochoric (at constant volume), also referred to as iso-volumetric

- adiabatic (no heat is added or removed from the system during adiabatic process which is equivalent to saying that the entropy remains constant, if the process is also reversible.)

See also

- Drinking bird An example of a basic heat engine.

- Reciprocating engine for a general description of the mechanics of piston engines

- Heat pump

- Carnot heat engine

- Timeline of heat engine technology

- Thermosynthesis

References

- ^ Fundamentals of Classical Thermodynamics, 3rd ed. p. 159, (1985) by G.J. Van Wylen and R.E. Sonntag: "A heat engine may be defined as a device that operates in a thermodynamic cycle and does a certain amount of net positive work as a result of heat transfer from a high-temperature body and to a low-temperature body. Often the term heat engine is used in a broader sense to include all devices that produce work, either through heat transfer or combustion, even though the device does not operate in a thermodynamic cycle. The internal-combustion engine and the gas turbine are examples of such devices, and calling these heat engines is an acceptable use of the term."

- ^ Mechanical efficiency of heat engines, p. 1 (2007) by James R. Senf: "Heat engines are made to provide mechanical energy from thermal energy."

- ^ Thermal physics: entropy and free energies, by Joon Chang Lee (2002), Appendix A, p. 183: "A heat engine absorbs energy from a heat source and then converts it into work for us.","When the engine absorbs heat energy, the absorbed heat energy comes with entropy." (heat energy

), "When the engine performs work, on the other hand, no entropy leaves the engine. This is problematic. We would like the engine to repeat the process again and again to provide us with a steady work source.[..] In order to do so, the working substance inside the engine must return to its initial thermodynamic condition after a cycle, which requires to remove the remaining entropy. The engine can do this only in one way. It must let part of the absorbed heat energy leave without converting it into work. Therefore the engine cannot convert all of the input energy into work!"

), "When the engine performs work, on the other hand, no entropy leaves the engine. This is problematic. We would like the engine to repeat the process again and again to provide us with a steady work source.[..] In order to do so, the working substance inside the engine must return to its initial thermodynamic condition after a cycle, which requires to remove the remaining entropy. The engine can do this only in one way. It must let part of the absorbed heat energy leave without converting it into work. Therefore the engine cannot convert all of the input energy into work!" - ^ "Efficiency by the Numbers" by Lee S. Langston

- ^ Cyclone Power Technologies Website

- ^ N. A. Sinitsyn (2011). "Fluctuation Relation for Heat Engines". J. Phys. A: Math. Theor. 44: 405001.

- ^ Nuclear Reactors Concepts and Thermodynamic Cycles

- Notes

- Kroemer, Herbert; Kittel, Charles (1980). Thermal Physics (2nd ed. ed.). W. H. Freeman Company. ISBN 0-7167-1088-9.

- Callen, Herbert B. (1985). Thermodynamics and an Introduction to Thermostatistics (2nd ed. ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.. ISBN 0-471-86256-8.

- On line museum of toy steam engines, including a very rare Bing heat engine

External links

- Video of Stirling engine running on dry ice

- Heat Engine

- On line museum of toy steam engines, including a very rare Bing heat engine

- Webarchive backup: Refrigeration Cycle Citat: "...The refrigeration cycle is basically the Rankine cycle run in reverse..."

- Red Rock Energy Solar Heliostats: Heat Engine Projects Citat: "...Choosing a Heat Engine..."

- Overview of heat engine types - not working

- The rotary piston array machine

- The gyroscope combustion motor

- The external combustion air engine

- Super-efficient Atkinson-Diesel Cycle

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

(Note: Units

(Note: Units