Hausdorff space

| Separation Axioms in Topological Spaces |

| Kolmogorov (T0) version |

|---|

| T0 | T1 | T2 | T2½ | completely T2 T3 | T3½ | T4 | T5 | T6 |

In topology and related branches of mathematics, a Hausdorff space, separated space or T2 space is a topological space in which distinct points have disjoint neighbourhoods. Of the many separation axioms that can be imposed on a topological space, the "Hausdorff condition" (T2) is the most frequently used and discussed. It implies the uniqueness of limits of sequences, nets, and filters. Intuitively, the condition is illustrated by the pun that a space is Hausdorff if any two points can be "housed off" from each other by open sets.[1]

Hausdorff spaces are named for Felix Hausdorff, one of the founders of topology. Hausdorff's original definition of a topological space (in 1914) included the Hausdorff condition as an axiom.

Contents |

Definitions

Points x and y in a topological space X can be separated by neighbourhoods if there exists a neighbourhood U of x and a neighbourhood V of y such that U and V are disjoint (U ∩ V = ∅). X is a Hausdorff space if any two distinct points of X can be separated by neighborhoods. This condition is the third separation axiom (after T0 and T1), which is why Hausdorff spaces are also called T2 spaces. The name separated space is also used.

A related, but weaker, notion is that of a preregular space. X is a preregular space if any two topologically distinguishable points can be separated by neighbourhoods. Preregular spaces are also called R1 spaces.

The relationship between these two conditions is as follows. A topological space is Hausdorff if and only if it is both preregular (i.e. topologically distinguishable points are separated) and Kolmogorov (i.e. distinct points are topologically distinguishable). A topological space is preregular if and only if its Kolmogorov quotient is Hausdorff.

Equivalences

For a topological space X, the following are equivalent:

- X is a Hausdorff space.

- Limits of nets in X are unique.[2]

- Limits of filters on X are unique.[3]

- Any singleton set {x} ⊂ X is equal to the intersection of all closed neighbourhoods of x.[4] (A closed neighbourhood of x is a closed set that contains an open set containing x.)

- The diagonal Δ = {(x,x) | x ∈ X} is closed as a subset of the product space X × X.

Examples and counterexamples

Almost all spaces encountered in analysis are Hausdorff; most importantly, the real numbers (under the standard metric topology on real numbers) are a Hausdorff space. More generally, all metric spaces are Hausdorff. In fact, many spaces of use in analysis, such as topological groups and topological manifolds, have the Hausdorff condition explicitly stated in their definitions.

A simple example of a topology that is T1 but is not Hausdorff is the cofinite topology defined on an infinite set.

Pseudometric spaces typically are not Hausdorff, but they are preregular, and their use in analysis is usually only in the construction of Hausdorff gauge spaces. Indeed, when analysts run across a non-Hausdorff space, it is still probably at least preregular, and then they simply replace it with its Kolmogorov quotient, which is Hausdorff.

In contrast, non-preregular spaces are encountered much more frequently in abstract algebra and algebraic geometry, in particular as the Zariski topology on an algebraic variety or the spectrum of a ring. They also arise in the model theory of intuitionistic logic: every complete Heyting algebra is the algebra of open sets of some topological space, but this space need not be preregular, much less Hausdorff.

While the existence of unique limits for convergent nets and filters imply that a space is Hausdorff, there are non-Hausdorff T1 spaces in which every convergent sequence has a unique limit.[5]

Properties

Subspaces and products of Hausdorff spaces are Hausdorff,[6] but quotient spaces of Hausdorff spaces need not be Hausdorff. In fact, every topological space can be realized as the quotient of some Hausdorff space.[7]

Hausdorff spaces are T1, meaning that all singletons are closed. Similarly, preregular spaces are R0.

Another nice property of Hausdorff spaces is that compact sets are always closed.[8] This may fail in non-Hausdorff spaces such as Sierpiński space.

The definition of a Hausdorff space says that points can be separated by neighborhoods. It turns out that this implies something which is seemingly stronger: in a Hausdorff space every pair of disjoint compact sets can also be separated by neighborhoods,[9] in other words there is a neighborhood of one set and a neighborhood of the other, such that the two neighborhoods are disjoint. This is an example of the general rule that compact sets often behave like points.

Compactness conditions together with preregularity often imply stronger separation axioms. For example, any locally compact preregular space is completely regular. Compact preregular spaces are normal, meaning that they satisfy Urysohn's lemma and the Tietze extension theorem and have partitions of unity subordinate to locally finite open covers. The Hausdorff versions of these statements are: every locally compact Hausdorff space is Tychonoff, and every compact Hausdorff space is normal Hausdorff.

The following results are some technical properties regarding maps (continuous and otherwise) to and from Hausdorff spaces.

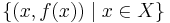

Let f : X → Y be a continuous function and suppose Y is Hausdorff. Then the graph of f,  , is a closed subset of X × Y.

, is a closed subset of X × Y.

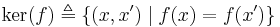

Let f : X → Y be a function and let  be its kernel regarded as a subspace of X × X.

be its kernel regarded as a subspace of X × X.

- If f is continuous and Y is Hausdorff then ker(f) is closed.

- If f is an open surjection and ker(f) is closed then Y is Hausdorff.

- If f is a continuous, open surjection (i.e. an open quotient map) then Y is Hausdorff if and only if ker(f) is closed.

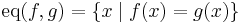

If f,g : X → Y are continuous maps and Y is Hausdorff then the equalizer  is closed in X. It follows that if Y is Hausdorff and f and g agree on a dense subset of X then f = g. In other words, continuous functions into Hausdorff spaces are determined by their values on dense subsets.

is closed in X. It follows that if Y is Hausdorff and f and g agree on a dense subset of X then f = g. In other words, continuous functions into Hausdorff spaces are determined by their values on dense subsets.

Let f : X → Y be a closed surjection such that f−1(y) is compact for all y ∈ Y. Then if X is Hausdorff so is Y.

Let f : X → Y be a quotient map with X a compact Hausdorff space. Then the following are equivalent

- Y is Hausdorff

- f is a closed map

- ker(f) is closed

Preregularity versus regularity

All regular spaces are preregular, as are all Hausdorff spaces. There are many results for topological spaces that hold for both regular and Hausdorff spaces. Most of the time, these results hold for all preregular spaces; they were listed for regular and Hausdorff spaces separately because the idea of preregular spaces came later. On the other hand, those results that are truly about regularity generally don't also apply to nonregular Hausdorff spaces.

There are many situations where another condition of topological spaces (such as paracompactness or local compactness) will imply regularity if preregularity is satisfied. Such conditions often come in two versions: a regular version and a Hausdorff version. Although Hausdorff spaces aren't generally regular, a Hausdorff space that is also (say) locally compact will be regular, because any Hausdorff space is preregular. Thus from a certain point of view, it is really preregularity, rather than regularity, that matters in these situations. However, definitions are usually still phrased in terms of regularity, since this condition is better known than preregularity.

See History of the separation axioms for more on this issue.

Variants

The terms "Hausdorff", "separated", and "preregular" can also be applied to such variants on topological spaces as uniform spaces, Cauchy spaces, and convergence spaces. The characteristic that unites the concept in all of these examples is that limits of nets and filters (when they exist) are unique (for separated spaces) or unique up to topological indistinguishability (for preregular spaces).

As it turns out, uniform spaces, and more generally Cauchy spaces, are always preregular, so the Hausdorff condition in these cases reduces to the T0 condition. These are also the spaces in which completeness makes sense, and Hausdorffness is a natural companion to completeness in these cases. Specifically, a space is complete if and only if every Cauchy net has at least one limit, while a space is Hausdorff if and only if every Cauchy net has at most one limit (since only Cauchy nets can have limits in the first place).

Algebra of functions

The algebra of continuous (real or complex) functions on a Hausdorff space is a commutative C*-algebra, and conversely by the Banach–Stone theorem one can recover the topology of the space from the algebraic properties of its algebra of continuous functions. This leads to noncommutative geometry, where one considers noncommutative C*-algebras as representing algebras of functions on a noncommutative space.

See also

Notes

- ^ Colin Adams and Robert Franzosa. Introduction to Topology: Pure and Applied. p. 42

- ^ Willard, pp. 86–87.

- ^ Willard, pp. 86–87.

- ^ Bourbaki, p. 75.

- ^ van Douwen, Eric K. (1993). "An anti-Hausdorff Fréchet space in which convergent sequences have unique limits". Topology and its Applications 51 (2): 147–158. doi:10.1016/0166-8641(93)90147-6.

- ^ Hausdorff property is hereditary on PlanetMath

- ^ Shimrat, M. (1956). "Decomposition spaces and separation properties". Quart. J. Math. 2: 128–129.

- ^ Proof of A compact set in a Hausdorff space is closed on PlanetMath

- ^ Willard, p. 124.

References

- Arkhangelskii, A.V., L.S. Pontryagin, General Topology I, (1990) Springer-Verlag, Berlin. ISBN 3-540-18178-4

- Bourbaki; Elements of Mathematics: General Topology, Addison-Wesley (1966).

- Willard, Stephen (2004). General Topology. Dover Publications. ISBN 0486434796.