Hardy–Littlewood circle method

In mathematics, the Hardy–Littlewood circle method is one of the most frequently used techniques of analytic number theory. It is named for G. H. Hardy and J. E. Littlewood, who developed it in a series of papers on Waring's problem.

Contents |

History

The initial germ of the idea is usually attributed to the work of Hardy with Srinivasa Ramanujan a few years earlier, in 1916 and 1917, on the asymptotics of the partition function. It was taken up by many other researchers, including Harold Davenport and I. M. Vinogradov, who modified the formulation slightly (moving from complex analysis to exponential sums), without changing the broad lines. Hundreds of papers followed, and as of 2005[update] the method still yields results. The method is the subject of a monograph by R. C. Vaughan.

Outline

The goal is to prove asymptotic behavior of a series: to show that an ~ F(n) for some function. This is done by taking the generating function of the series, then computing the residues about zero (essentially the Fourier coefficients). Technically, the generating function is scaled to have radius of convergence 1, so it has singularities on the unit circle – thus one cannot take the contour integral over the unit circle.

The circle method is specifically how to compute these residues, by partitioning the circle into minor arcs (the bulk of the circle) and major arcs (small arcs containing the most significant singularities), and then bounding the behavior on the minor arcs. The key insight is that, in many cases of interest (such as theta functions), the singularities occur at the roots of unity, and the significance of the singularities is in the order of the Farey sequence. Thus one can investigate the most significant singularities, and, if fortunate, compute the integrals.

Setup

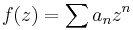

The circle in question was initially the unit circle in the complex plane. Assuming the problem had first been formulated in the terms that for a sequence of complex numbers

- an, n = 0, 1, 2, 3, ...

we want some asymptotic information of the type

- an ~ F(n)

where we have some heuristic reason to guess the form taken by F (an ansatz), we write

a power series generating function. The interesting cases are where f is then of radius of convergence equal to 1, and we suppose that the problem as posed has been modified to present this situation.

Residues

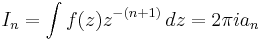

From that formulation, it is direct from the residue theorem that

for integers n ≥ 0, where the integral is taken over the circle of radius r and centred at 0, for any r with

- 0 < r < 1.

That is, this is a contour integral, with the contour being the circle described traversed once anti-clockwise. So far, this is relatively elementary. We would like to take r = 1 directly, i.e. to use the unit circle contour. In the complex analysis formulation this is problematic, since the values of f are not in general defined there.

Singularities on unit circle

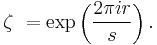

The problem addressed by the circle method is to force the issue of taking r = 1, by a good understanding of the nature of the singularities f exhibits on the unit circle. The fundamental insight is the role played by the Farey sequence of rational numbers, or equivalently by the roots of unity

Here the denominator s, assuming that r/s is in lowest terms, turns out to determine the relative importance of the singular behaviour of typical f near ζ.

Method

The Hardy–Littlewood circle method, for the complex-analytic formulation, can then be thus expressed. The contributions to the evaluation of In, as r → 1, should be treated in two ways, traditionally called major arcs and minor arcs. We divide the ζ into two classes, according to whether s ≤ N, or s > N, where N is a function of n that is ours to choose conveniently. The integral In is divided up into integrals each on some arc of the circle that is adjacent to ζ, of length a function of s (again, at our discretion). The arcs make up the whole circle; the sum of the integrals over the major arcs is to make up 2πiF(n) (realistically, this will happen up to a manageable remainder term). The sum of the integrals over the minor arcs is to be replaced by an upper bound, smaller in order than F(n).

Discussion

Stated baldly like this, it is not at all clear that this can be made to work. Indeed, the insights involved are not so shallow. One clear source is the theory of theta functions.

Waring's problem

In the context of Waring's problem, powers of theta functions are the generating functions for sums of squares. Their analytic behaviour is known in much more accurate detail than for the cubes, for example.

It is the case, as the false-colour diagram indicates, that for a theta function the 'most important' point on the boundary circle is at z = 1; followed by z = −1, and then the two complex cube roots of unity at 7 o'clock and 11 o'clock. After that it is the fourth roots of unity i and −i that matter most. While nothing in this guarantees that the analytical method will work, it does explain the rationale of using a Farey series-type criterion on roots of unity.

In the Waring problem case, one takes a sufficiently high power of the generating function, to force the situation in which the singularities, organised into the so-called singular series, do predominate. The less wasteful the estimates used on the rest, the finer the results. As Bryan Birch has put it, the method is inherently wasteful. That does not apply to the partition function case, which signalled the possibility that in a favourable situation the losses from estimates could be controlled.

Vinogradov trigonometric sums

Later, I. M. Vinogradov extended the technique, replacing the exponential sum formulation f(z) with a finite Fourier series so that the relevant integral In is a Fourier coefficient. Vinogradov applied finite sums to Waring's problem in 1926, and the general trigometric sum method became known as "the circle method of Hardy, Littlewood and Ramanujan, in the form of Vinogradov's trigonometric sums"; found on pp. 387–8 of K. K. Mardzhanishvili (1985). Essentially all this does is to discard the whole 'tail' of the generating function, allowing the business of r in the limiting operation to be set directly to the value 1.

Applications

Refinements of the method have allowed results to be proved about the solutions of homogeneous Diophantine equations, as long as the number of variables k is large relative to the degree d (see Birch's theorem for example). This turns out to be a contribution to the Hasse principle, capable of yielding quantitative information. If d is fixed and k is small, other methods are required, and indeed the Hasse principle tends to fail.

Rademacher's contour

In the special case when the circle method is applied to find the coefficients of a modular form of negative weight, Hans Rademacher found a modification of the contour that makes the series arising from the circle method converge to the exact result. To describe his contour, it is convenient to replace the unit circle by the upper half plane, by making the substitution z = exp(2πiτ), so that the contour integral becomes an integral from τ = i to τ = 1 + i. (The number i could be replaced by any number on the upper half plane, but i is the most convenient choice.) Rademacher's contour is (more or less) given by the boundaries of all the Ford circles from 0 to 1, as shown in the diagram. The replacement of the line from i to 1 + i by the boundaries of these circles is a non-trivial limiting process, which can be justified for modular forms that have negative weight, and with more care can also be justified for non-constant terms for the case of weight 0 (in other words modular functions).

References

- Apostol, Tom M. (1990), Modular functions and Dirichlet series in number theory (2nd ed.), Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-97127-8

- K. K. Mardzhanishvili, Ivan Matveevich Vinogradov : a brief outline of his life and works, in I. M. Vinogradov, Selected works (Berlin, 1985)

- Rademacher, Hans (1943), "On the expansion of the partition function in a series", Annals of Mathematics. Second Series (The Annals of Mathematics, Vol. 44, No. 3) 44 (3): 416–422, doi:10.2307/1968973, JSTOR 1968973, MR0008618

- Vaughan, R. C. (1997), The Hardy–Littlewood Method, Cambridge Tracts in Mathematics, 125 (2nd ed.), Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9780521573474