Hamming(7,4)

| Hamming(7,4)-Code | |

|---|---|

| Named after | Richard W. Hamming |

| Classification | |

| Type | Linear block code |

| Parameters | |

| Block length | 7 |

| Message length | 4 |

| Rate | 4/7 ~ 0.571 |

| Distance | 3 |

| Alphabet size | 2 |

| Notation | ![[7,4,3]_2](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/e4d0d4aefac6c4060622830e99cee510.png) -code -code |

| Properties | |

| perfect code | |

In coding theory, Hamming(7,4) is a linear error-correcting code that encodes 4 bits of data into 7 bits by adding 3 parity bits. It is a member of a larger family of Hamming codes, but the term Hamming code often refers to this specific code that Richard W. Hamming introduced in 1950. At the time, Hamming worked at Bell Telephone Laboratories and was frustrated with the erroneous punched card reader, which is why he started working on error-correcting codes.[1]

The Hamming code adds three additional check bits to every four data bits of the message. Hamming's (7,4) algorithm can correct any single-bit error, or detect all single-bit and two-bit errors. In other words, the Hamming distance between any two correct codewords is 3, and received words can be correctly decoded if they are at distance at most one from the codeword that was transmitted by the sender. This means that for transmission medium situations where burst errors do not occur, Hamming's (7,4) code is effective (as the medium would have to be extremely noisy for 2 out of 7 bits to be flipped).

Contents |

Goal

The goal of Hamming codes is to create a set of parity bits that overlap such that a single-bit error (the bit is logically flipped in value) in a data bit or a parity bit can be detected and corrected. While multiple overlaps can be created, the general method is presented in Hamming codes.

-

Bit # 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Transmitted bit

Yes No Yes No Yes No Yes

No Yes Yes No No Yes Yes

No No No Yes Yes Yes Yes

This table describes which parity bits cover which transmitted bits in the encoded word. For example,  provides and even parity for bits 2, 3, 6, & 7. It also details which transmitted by which parity bit by reading the column. For example,

provides and even parity for bits 2, 3, 6, & 7. It also details which transmitted by which parity bit by reading the column. For example,  is covered by

is covered by  and

and  but not

but not  . This table will have a striking resemblance to the parity-check matrix (

. This table will have a striking resemblance to the parity-check matrix ( ) in the next section.

) in the next section.

Furthermore, if the parity columns in the above table were removed

-

Yes Yes No Yes

Yes No Yes Yes

No Yes Yes Yes

then resemblance to rows 1, 2, & 4 of the code generator matrix ( ) below will also be evident.

) below will also be evident.

So, by picking the parity bit coverage correctly, all errors of Hamming distance of 1 can be detected and corrected, which is the point of using a Hamming code.

Hamming matrices

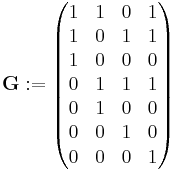

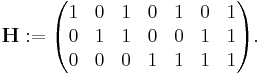

Hamming codes can be computed in linear algebra terms through matrices because Hamming codes are linear codes. For the purposes of Hamming codes, two Hamming matrices can be defined: the code generator matrix  and the parity-check matrix

and the parity-check matrix  :

:

and

As mentioned above, rows 1, 2, & 4 of  should look familiar as they map the data bits to their parity bits:

should look familiar as they map the data bits to their parity bits:

covers

covers  ,

,  ,

,

covers

covers  ,

,  ,

,

covers

covers  ,

,  ,

,

The remaining rows (3, 5, 6, 7) map the data to their position in encoded form and there is only 1 in that row so it is an identical copy. In fact, these four rows are linearly independent and form the identity matrix (by design, not coincidence).

Also as mentioned above, the three rows of  should be familiar. These rows are used to compute the syndrome vector at the receiving end and if the syndrome vector is the null vector (all zeros) then the received word is error-free; if non-zero then the value indicates which bit has been flipped.

should be familiar. These rows are used to compute the syndrome vector at the receiving end and if the syndrome vector is the null vector (all zeros) then the received word is error-free; if non-zero then the value indicates which bit has been flipped.

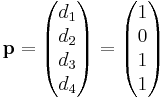

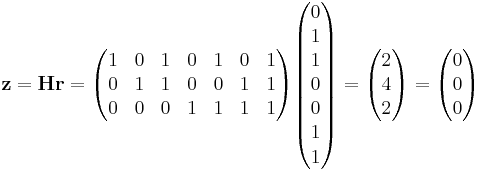

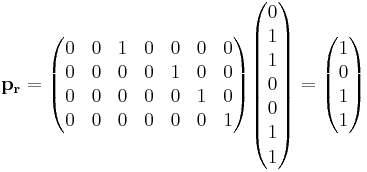

The 4 data bits — assembled as a vector  — is pre-multiplied by

— is pre-multiplied by  (i.e.,

(i.e.,  ) and taken modulo 2 to yield the encoded value that is transmitted. The original 4 data bits are converted to 7 bits (hence the name "Hamming(7,4)") with 3 parity bits added to ensure even parity using the above data bit coverages. The first table above shows the mapping between each data and parity bit into its final bit position (1 through 7) but this can also be presented in a Venn diagram. The first diagram in this article shows three circles (one for each parity bit) and encloses data bits that each parity bit covers. The second diagram (shown to the right) is identical but, instead, the bit positions are marked.

) and taken modulo 2 to yield the encoded value that is transmitted. The original 4 data bits are converted to 7 bits (hence the name "Hamming(7,4)") with 3 parity bits added to ensure even parity using the above data bit coverages. The first table above shows the mapping between each data and parity bit into its final bit position (1 through 7) but this can also be presented in a Venn diagram. The first diagram in this article shows three circles (one for each parity bit) and encloses data bits that each parity bit covers. The second diagram (shown to the right) is identical but, instead, the bit positions are marked.

For the remainder of this section, the following 4 bits (shown as a column vector) will be used as a running example:

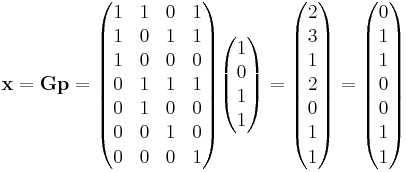

Channel coding

Suppose we want to transmit this data over a noisy communications channel. Specifically, a binary symmetric channel meaning that error corruption does not favor either zero or one (it is symmetric in causing errors). Furthermore, all source vectors are assumed to be equiprobable. We take the product of G and p, with entries modulo 2, to determine the transmitted codeword x:

This means that 0110011 would be transmitted instead of transmitting 1011.

In the diagram to the right, the 7 bits of the encoded word are inserted into their respective locations; from inspection it is clear that the parity of the red, green, and blue circles are even:

- red circle has 2 1's

- green circle has 2 1's

- blue circle has 4 1's

What will be shown shortly is that if, during transmission, a bit is flipped then the parity of 2 or all 3 circles will be incorrect and the errored bit can be determined (even if one of the parity bits) by knowing that the parity of all three of these circles should be even.

Parity check

If no error occurs during transmission, then the received codeword  is identical to the transmitted codeword

is identical to the transmitted codeword  :

:

The receiver multiplies  and

and  to obtain the syndrome vector

to obtain the syndrome vector  , which indicates whether an error has occurred, and if so, for which codeword bit. Performing this multiplication (again, entries modulo 2):

, which indicates whether an error has occurred, and if so, for which codeword bit. Performing this multiplication (again, entries modulo 2):

Since the syndrome  is the null vector, the receiver can conclude that no error has occurred. This conclusion is based on the observation that when the data vector is multiplied by

is the null vector, the receiver can conclude that no error has occurred. This conclusion is based on the observation that when the data vector is multiplied by  , a change of basis occurs into a vector subspace that is the kernel of

, a change of basis occurs into a vector subspace that is the kernel of  . As long as nothing happens during transmission,

. As long as nothing happens during transmission,  will remain in the kernel of

will remain in the kernel of  and the multiplication will yield the null vector.

and the multiplication will yield the null vector.

Error correction

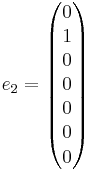

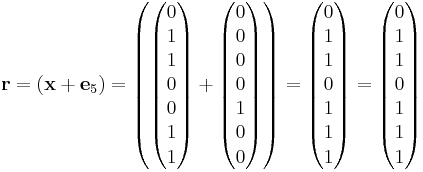

Otherwise, suppose a single bit error has occurred. Mathematically, we can write

modulo 2, where  is the

is the  unit vector, that is, a zero vector with a 1 in the

unit vector, that is, a zero vector with a 1 in the  , counting from 1.

, counting from 1.

Thus the above expression signifies a single bit error in the  place.

place.

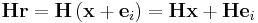

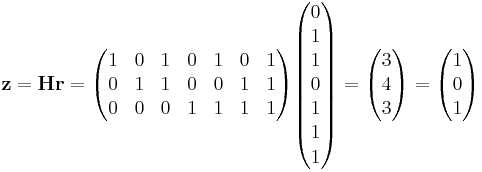

Now, if we multiply this vector by  :

:

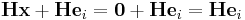

Since  is the transmitted data, it is without error, and as a result, the product of

is the transmitted data, it is without error, and as a result, the product of  and

and  is zero. Thus

is zero. Thus

Now, the product of  with the

with the  standard basis vector picks out that column of

standard basis vector picks out that column of  , we know the error occurs in the place where this column of

, we know the error occurs in the place where this column of  occurs. HaMmiNg

occurs. HaMmiNg

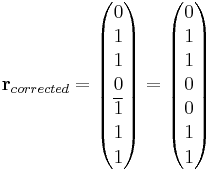

For example, suppose we have introduced a bit error on bit #5

The diagram to the right shows the bit error (shown in blue text) and the bad parity created (shown in red text) in the red and green circles. The bit error can be detected by computing the parity of the red, green, and blue circles. If a bad parity is detected then the data bit that overlaps only the bad parity circles is the bit with the error. In the above example, the red & green circles have bad parity so the bit corresponding to the intersection of red & green but not blue indicates the errored bit.

Now,

which corresponds to the fifth column of  . Furthermore, the general algorithm used (see Hamming code#General algorithm) was intentional in its construction so that the syndrome of 101 corresponds to the binary value of 5, which indicates the fifth bit was corrupted. Thus, an error has been detected in bit 5, and can be corrected (simply flip or negate its value):

. Furthermore, the general algorithm used (see Hamming code#General algorithm) was intentional in its construction so that the syndrome of 101 corresponds to the binary value of 5, which indicates the fifth bit was corrupted. Thus, an error has been detected in bit 5, and can be corrected (simply flip or negate its value):

This corrected received value indeed, now, matches the transmitted value  from above.

from above.

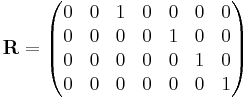

Decoding

Once the received vector has been determined to be error-free or corrected if an error occurred (assuming only zero or one bit errors are possible) then the received data needs to be decoded back into the original 4 bits.

First, define a matrix  :

:

Then the received value,  is

is

and using the running example from above

Multiple bit errors

It is not difficult to show that only single bit errors can be corrected using this scheme. Alternatively, Hamming codes can be used to detect single and double bit errors, by merely noting that the product of H is nonzero whenever errors have occurred. In the diagram to the right, bits 4 & 5 were flipped. This yields only one circle (green) with an invalid parity but the errors are not recoverable.

However, the Hamming (7,4) and similar Hamming codes cannot distinguish between single-bit errors and two-bit errors. That is, two-bit errors appear the same as one-bit errors. If error correction is performed on a two-bit error the result will be incorrect.

All codes

Since the source is only 4 bits then there are only 16 possible transmitted words. Included is the 8-bit value if an extra parity bit is used (see Hamming(7,4) code with an additional parity bit). (The data bits are shown in blue; the parity bits are shown in red; and the extra parity bit shown in green.)

Data |

Hamming(7,4) | Hamming(7,4) with extra parity bit (Hamming(8,4)) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Transmitted |

Diagram | Transmitted |

Diagram | |

| 0000 | 0000000 | 00000000 | ||

| 1000 | 1110000 | 11100001 | ||

| 0100 | 1001100 | 10011001 | ||

| 1100 | 0111100 | 01111000 | ||

| 0010 | 0101010 | 01010101 | ||

| 1010 | 1011010 | 10110100 | ||

| 0110 | 1100110 | 11001100 | ||

| 1110 | 0010110 | 00101101 | ||

| 0001 | 1101001 | 11010010 | ||

| 1001 | 0011001 | 00110011 | ||

| 0101 | 0100101 | 01001011 | ||

| 1101 | 1010101 | 10101010 | ||

| 0011 | 1000011 | 10000111 | ||

| 1011 | 0110011 | 01100110 | ||

| 0111 | 0001111 | 00011110 | ||

| 1111 | 1111111 | 11111111 | ||

References

- ^ "History of Hamming Codes". http://biobio.loc.edu/chu/web/Courses/Cosi460/hamming_codes.htm. Retrieved 2008-04-03.