Group cohomology

In abstract algebra, homological algebra, algebraic topology and algebraic number theory, as well as in applications to group theory proper, group cohomology is a way to study groups using a sequence of functors H n. The study of fixed points of groups acting on modules and quotient modules is a motivation, but the cohomology can be defined using various constructions. There is a dual theory, group homology, and a generalization to non-abelian coefficients.

These algebraic ideas are closely related to topological ideas. Thus, the group cohomology of a group G can be thought of as, and is motivated by, the singular cohomology of a suitable space having G as its fundamental group, namely the corresponding Eilenberg-MacLane space. Thus, the group cohomology of  can be thought of as the singular cohomology of the circle

can be thought of as the singular cohomology of the circle  , and similarly for

, and similarly for  and

and  .

.

A great deal is known about the cohomology of groups, including interpretations of low dimensional cohomology, functorality, and how to change groups. The subject of group cohomology began in the 1920s, matured in the late 1940s, and continues as an area of active research today.

Contents |

Motivation

A general paradigm in group theory is that a group G should be studied via its group representations. A slight generalization of those representations are the G-modules: a G-module is an abelian group M together with a group action of G on M, with every element of G acting as an endomorphism of M. In the sequel we will write G multiplicatively and M additively.

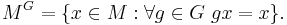

Given such a G-module M, it is natural to consider the subgroup of G-invariant elements:

Now, if N is a submodule of M (i.e. a subgroup of M mapped to itself by the action of G), it isn't in general true that the invariants in M/N are found as the quotient of the invariants in M by those in N: being invariant 'modulo N ' is broader. The first group cohomology H1(G,N) precisely measures the difference. The group cohomology functors Hn in general measure the extent to which taking invariants doesn't respect exact sequences. This is expressed by a long exact sequence.

Formal constructions

In this article, G is a finite group. The collection of all G-modules is a category (the morphisms are group homomorphisms f with the property f(gx) = g(f(x)) for all g in G and x in M). This category of G-modules is an abelian category with enough injectives (since it is isomorphic to the category of all modules over the group ring ℤ[G]).

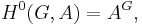

Sending each module M to the group of invariants MG yields a functor from this category to the category  of abelian groups. This functor is left exact but not necessarily right exact. We may therefore form its right derived functors; their values are abelian groups and they are denoted by Hn(G,M), "the n-th cohomology group of G with coefficients in M". H0(G,M) is identified with MG.

of abelian groups. This functor is left exact but not necessarily right exact. We may therefore form its right derived functors; their values are abelian groups and they are denoted by Hn(G,M), "the n-th cohomology group of G with coefficients in M". H0(G,M) is identified with MG.

Long exact sequence of cohomology

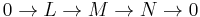

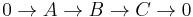

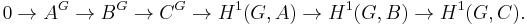

In practice, one often computes the cohomology groups using the following fact: if

is a short exact sequence of G-modules, then a long exact sequence

is induced. The maps δn are called the "connecting homomorphisms" and can be obtained from the snake lemma.[1]

Cochain complexes

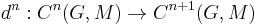

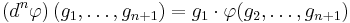

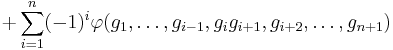

Rather than using the machinery of derived functors, the cohomology groups can also be defined more concretely, as follows.[2] For n ≥ 0, let Cn(G, M) be the group of all functions from Gn to M. This is an abelian group; its elements are called the (inhomogeneous) n-cochains. The coboundary homomorphisms

are defined as

The crucial thing to check here is

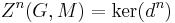

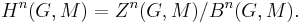

thus we have a cochain complex and we can compute cohomology. For n ≥ 0, define the group of n-cocycles as:

and the group of n-coboundaries as

and

The functors Extn and formal definition of group cohomology

Yet another approach is to treat G-modules as modules over the group ring ℤ[G], which allows one to define group cohomology via Ext functors:

where M is a ℤ[G]-module.

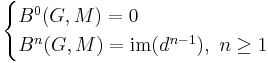

Here ℤ is treated as the trivial G-module: every element of G acts as the identity. These Ext groups can also be computed via a projective resolution of ℤ, the advantage being that such a resolution only depends on G and not on M. We recall the definition of Ext more explicitly for this context. Let F be a projective ℤ[G]-resolution (e.g. a free ℤ[G]-resolution) of the trivial ℤ[G]-module ℤ:

e.g., one may always take the resolution of group rings, ![F_n = \mathbb Z[G^{n%2B1}]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/ab354bf78daabb263099309ae049d2cd.png) , with morphisms

, with morphisms

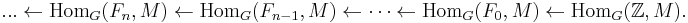

Recall that for ℤ[G]-modules N and M, HomG(N, M) is an abelian group consisting of ℤ[G]-homomorphisms from N to M. Since HomG(–, M) is a contravariant functor and reverses the arrows, applying HomG(–, M) to F termwise produces a cochain complex HomG(F, M):

The cohomology groups H*(G,M) of G with coefficients in M are defined as the cohomology of the above cochain complex:

- Hn(G,M)=Hn(HomG(F, M))

for n ≥ 0.

Group homology

Dually to the construction of group cohomology there is the following definition of group homology: given a G-module M, set DM to be the submodule generated by elements of the form g·m-m, g∈G, m∈M. Assigning to M its so-called coinvariants, the quotient

,

,

is a right exact functor. Its left derived functors are by definition the group homology

.

.

Note that the superscript/subscript convention for cohomology/homology agrees with the convention for group invariants/coinvariants, while which is denoted "co-" switches:

- superscripts correspond to cohomology

and invariants

and invariants  while

while - subscripts correspond to homology

and coinvariants

and coinvariants

The covariant functor which assigns MG to M is isomorphic to the functor which sends M to ![\mathbb{Z}\otimes_{\mathbb{Z}[G]}M](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/44e62604ae420a4459c74d54143c5411.png) , where

, where  is endowed with the trivial G-action. Hence one also gets an expression for group homology in terms of the Tor functors,

is endowed with the trivial G-action. Hence one also gets an expression for group homology in terms of the Tor functors,

Recall that the tensor product ![N\otimes_{\mathbb{Z}[G]}M](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/0377476621d64677dfb870987ebfbfa1.png) is defined whenever N is a right ℤ[G]-module and M is a left ℤ[G]-module. If N is a left ℤ[G]-module, we turn it into a right ℤ[G]-module by setting a g = g− 1 a for every g ∈ G and every a ∈ N. This convention allows to define the tensor product

is defined whenever N is a right ℤ[G]-module and M is a left ℤ[G]-module. If N is a left ℤ[G]-module, we turn it into a right ℤ[G]-module by setting a g = g− 1 a for every g ∈ G and every a ∈ N. This convention allows to define the tensor product ![N\otimes_{\mathbb{Z}[G]}M](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/0377476621d64677dfb870987ebfbfa1.png) in the case where both M and N are left ℤ[G]-modules.

in the case where both M and N are left ℤ[G]-modules.

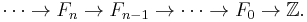

Specifically, the homology groups Hn(G, M) can be computed as follows. Start with a projective resolution F of the trivial ℤ[G]-module ℤ, as in the previous section. Apply the covariant functor ![\otimes_{\mathbb{Z}[G]}M](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/af6e24045f278b70fdb9e9c41d20f2c3.png) to F termwise to get a chain complex

to F termwise to get a chain complex ![F\otimes_{\mathbb{Z}[G]}M](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/e5bfc2e60160bf6d67df55249e89e0fe.png) :

:

Then Hn(G, M) are the homology groups of this chain complex, ![H_n(G,M)=H_n(F\otimes_{\mathbb{Z}[G]}M)](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/9847674205421099004a949a210380e4.png) for n ≥ 0.

for n ≥ 0.

Group homology and cohomology can be treated uniformly for some groups, especially finite groups, in terms of complete resolutions and the Tate cohomology groups.

Functorial maps in terms of cochains

Connecting homomorphisms

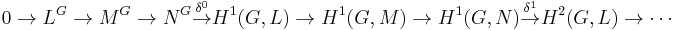

For a short exact sequence 0 → L → M → N → 0, the connecting homomorphisms δn : Hn(G, N) → Hn+1(G, L) can be described in terms of inhomogeneous cochains as follows.[3] If c is an element of Hn(G, N) represented by an n-cocycle φ : Gn → N, then δn(c) is represented by dn(ψ), where ψ is an n-cochain Gn → M "lifting" φ (i.e. such that φ is the composition of ψ with the surjective map M → N).

Non-abelian group cohomology

Using the G-invariants and the 1-cochains, one can construct the zeroth and first group cohomology for a group G with coefficients in a non-abelian group. Specifically, a G-group is a (not necessarily abelian) group A together with an action by G.

The zeroth cohomology of G with coefficients in A is defined to be the subgroup

of A.

The first cohomology of G with coefficents in A is defined as 1-cocycles modulo an equivalence relation instead of by 1-coboundaries. The condition for a map φ to be a 1-cocycle is that ![\varphi(gh)=\varphi(g)[g \varphi(h)]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/15c0dbb966f73bf4390fbc80eaadc961.png) and

and  if there is an a in A such that

if there is an a in A such that  . In general,

. In general,  is not a group when A is non-abelian. It instead has the structure of a pointed set – exactly the same situation arises in the 0th homotopy group,

is not a group when A is non-abelian. It instead has the structure of a pointed set – exactly the same situation arises in the 0th homotopy group,  which for a general topological space is not a group but a pointed set. Note that a group is in particular a pointed set, with the identity element as distinguished point.

which for a general topological space is not a group but a pointed set. Note that a group is in particular a pointed set, with the identity element as distinguished point.

Using explicit calculations, one still obtains a truncated long exact sequence in cohomology. Specifically, let

be a short exact sequence of G-groups, then there is an exact sequence of pointed sets

Connections with topological cohomology theories

Group cohomology can be related to topological cohomology theories: to the topological group G there is an associated classifying space BG. (If G has no topology about which we care, then we assign the discrete topology to G. In this case, BG is an Eilenberg-MacLane space K(G,1), whose fundamental group is G and whose higher homotopy groups vanish). The n-th cohomology of BG, with coefficients in M (in the topological sense), is the same as the group cohomology of G with coefficients in M. This will involve a local coefficient system unless M is a trivial G-module. The connection holds because the total space EG is contractible, so its chain complex forms a projective resolution of M. These connections are explained in (Adem-Milgram 2004), Chapter II.

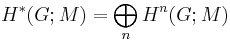

When M is a ring with trivial G-action, we inherit good properties which are familiar from the topological context: in particular, there is a cup product under which

is a graded module, and a Künneth formula applies.

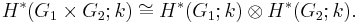

If, furthermore, M=k is a field, then  is a graded k-algebra. In this case, the Künneth formula yields

is a graded k-algebra. In this case, the Künneth formula yields

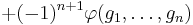

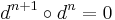

For example, let G be the group with two elements, under the discrete topology. The real projective space  is a classifying space for G. Let k=F2, the field of two elements. Then

is a classifying space for G. Let k=F2, the field of two elements. Then

a polynomial k-algebra on a single generator, since this is the cellular cohomology ring of  .

.

Hence, as a second example, if G is an elementary abelian 2-group of rank r, and k=F2, then the Künneth formula gives

![H^*(G;k)\cong k[x_1, \ldots, x_r]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/153f1962365963f4d5beb908f0ad4390.png) ,

,

a polynomial k-algebra generated by r classes in  .

.

Properties

In the following, let M be a G-module.

Functoriality

Group cohomology depends contravariantly on the group G, in the following sense: if f : H → G is a group homomorphism, then we have a naturally induced morphism Hn(G,M) → Hn(H,M) (where in the latter, M is treated as an H-module via f).

Given a morphism of G-modules M→N, one gets a morphism of cohomology groups in the Hn(G,M) → Hn(G,N).

H1

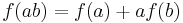

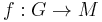

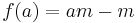

The first cohomology group is the quotient of the so-called crossed homomorphisms, i.e. maps (of sets)  satisfying

satisfying  for all

for all  in G, modulo the so-called principal crossed homomorphisms, i.e. maps

in G, modulo the so-called principal crossed homomorphisms, i.e. maps  given by

given by  for some fixed

for some fixed  . This follows from the definition of cochains above.

. This follows from the definition of cochains above.

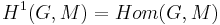

If the action of G on M is trivial, then the above boils down to  , the group of group homomorphisms

, the group of group homomorphisms  .

.

H2

If M is a trivial G-module (i.e. the action of G on M is trivial), the second cohomology group H2(G,M) is in one-to-one correspondence with the set of central extensions of G by M (up to a natural equivalence relation). More generally, if the action of G on M is nontrivial, H2(G,M) classifies the isomorphism classes of all extensions of G by M in which the induced action of G on M by inner automorphisms agrees with the given action.

Change of group

The Hochschild-Serre spectral sequence relates the cohomology of a normal subgroup N of G and the quotient G/N to the cohomology of the group G (for (pro-)finite groups G).

Cohomology of finite groups is torsion

The cohomology groups of finite groups are all torsion. Indeed, by Maschke's theorem the category of representations of a finite group is semi-simple over any field of characteristic zero (or more generally, any field whose characteristic does not divide the order of the group), hence, viewing group cohomology as a derived functor in this abelian category, one obtains that it is zero. The other argument is that over a field of characteristic zero, the group algebra of a finite group is a direct sum of matrix algebras (possibly over division algebras which are extensions of the original field), while a matrix algebra is Morita equivalent to its base field and hence has trivial cohomology.

History and relation to other fields

The low dimensional cohomology of a group was classically studied in other guises, long before the notion of group cohomology was formulated in 1943-45. The first theorem of the subject can be identified as Hilbert's Theorem 90 in 1897; this was recast into Noether's equations in Galois theory (an appearance of cocycles for H1). The idea of factor sets for the extension problem for groups (connected with H2) arose in the work of Hölder (1893), in Issai Schur's 1904 study of projective representations, in Schreier's 1926 treatment, and in Richard Brauer's 1928 study of simple algebras and the Brauer group. A fuller discussion of this history may be found in (Weibel 1999, pp. 806–811).

In 1941, while studying  (which plays a special role in groups), Hopf discovered what is now called Hopf's integral homology formula (Hopf 1942), which is identical to Schur's formula for the Schur multiplier of a finite, finitely presented group:

(which plays a special role in groups), Hopf discovered what is now called Hopf's integral homology formula (Hopf 1942), which is identical to Schur's formula for the Schur multiplier of a finite, finitely presented group:

![H_2(G,\mathbb{Z}) \cong (R \cap [F, F])/[F, R]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/ea4a80ede789fe7913dab0df6b222895.png) , where

, where  and F is a free group.

and F is a free group.

Hopf's result led to the independent discovery of group cohomology by several groups in 1943-45: Eilenberg and Mac Lane in the USA (Rotman 1995, p. 358); Hopf and Eckmann in Switzerland; and Freudenthal in the Netherlands (Weibel 1999, p. 807). The situation was chaotic because communication between these countries was difficult during World War II.

From a topological point of view, the homology and cohomology of G was first defined as the homology and cohomology of a model for the topological classifying space BG as discussed in #Connections with topological cohomology theories above. In practice, this meant using topology to produce the chain complexes used in formal algebraic definitions. From a module-theoretic point of view this was integrated into the Cartan-Eilenberg theory of Homological algebra in the early 1950s.

The application in algebraic number theory to class field theory provided theorems valid for general Galois extensions (not just abelian extensions). The cohomological part of class field theory was axiomatized as the theory of class formations. In turn, this led to the notion of Galois cohomology and étale cohomology (which builds on it) (Weibel 1999, p. 822). Some refinements in the theory post-1960 have been made, such as continuous cocycles and Tate's redefinition, but the basic outlines remain the same. This is a large field, and now basic in the theories of algebraic groups.

The analogous theory for Lie algebras, called Lie algebra cohomology, was first developed in the late 1940s, by Chevalley-Eilenberg, and Koszul (Weibel 1999, p. 810). It is formally similar, using the corresponding definition of invariant for the action of a Lie algebra. It is much applied in representation theory, and is closely connected with the BRST quantization of theoretical physics.

Notes

- ^ Section VII.2 of Serre 1979

- ^ Page 62 of Milne 2008 or section VII.3 of Serre 1979

- ^ Remark II.1.21 of Milne 2008

References

- Adem, Alejandro; R. James Milgram (2004), Cohomology of Finite Groups, Grundlehren der Mathematischen Wissenschaften, 309, Springer-Verlag, ISBN 3-540-20283-8, MR2035696

- Brown, Kenneth S. (1972), Cohomology of Groups, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 87, Springer Verlag, ISBN 0-387-90688-6, MR0672956

- Hopf, Heinz (1942), "Fundamentalgruppe und zweite Bettische Gruppe", Comment. Math. Helv. 14 (1): 257–309, doi:10.1007/BF02565622, MR6510, http://www.digizeitschriften.de/index.php?id=166&ID=132355&L=2

- Chapter II of Milne, James (5/2/2008), Class Field Theory, v4.00, http://www.jmilne.org/math, retrieved 8/9/2008

- Rotman, Joseph (1995), An Introduction to the Theory of Groups, Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-94285-8, MR1307623

- Chapter VII of Serre, Jean-Pierre (1979), Local fields, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 67, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-90424-5, MR554237

- Serre, Jean-Pierre (1994), Cohomologie galoisienne, Lecture Notes in Mathematics, 5 (Fifth ed.), Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-3-540-58002-7, MR1324577

- Shatz, Stephen S. (1972), Profinite groups, arithmetic, and geometry, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-08017-8, MR0347778

- Chapter 6 of Weibel, Charles A. (1994), An introduction to homological algebra, Cambridge Studies in Advanced Mathematics, 38, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-55987-4, OCLC 36131259, MR1269324

- Weibel, Charles A. (1999), "History of homological algebra", History of Topology, Cambridge University Press, pp. 797–836, ISBN 0-444-82375-1, MR1721123

![H^{n}(G,M) = \operatorname{Ext}^{n}_{\mathbb{Z}[G]}(\mathbb{Z},M),](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/1d0f008d6e3447ca49b6db8bcdbcc083.png)

![f_n�: \mathbb Z[G^{n%2B1}] \to \mathbb Z[G^n], \quad (g_0, g_1, \dots, g_n) \mapsto \sum_{i=0}^{n} (-1)^i(g_0, \dots, \widehat{g_i}, \dots, g_n).](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/66efc4516bb19abea9adbc4909f7721e.png)

![H_n(G,M) = \operatorname{Tor}_n^{\mathbb{Z}[G]}(\mathbb{Z},M)](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/22a8d6ab4fbf6248c06d4fa701a8b37f.png)

![\dots \to F_n\otimes_{\mathbb{Z}[G]}M\to F_{n-1}\otimes_{\mathbb{Z}[G]}M \to\dots \to F_0\otimes_{\mathbb{Z}[G]}M\to \mathbb Z\otimes_{\mathbb{Z}[G]}M.](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/6c111e1231722eeb8bc6e807bc086f98.png)

![H^*(G;k)\cong k[x],\,](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/eb263e3eee62572f750e62f78331d057.png)