Fundamental theorem of arithmetic

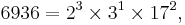

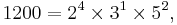

In number theory, the fundamental theorem of arithmetic (or the unique-prime-factorization theorem) states that any integer greater than 1 can be written as a unique product (up to ordering of the factors) of prime numbers. For example,

are two numbers satisfying the hypothesis of the theorem that can be written as the product of prime numbers.

Proof of existence of a prime factorization is straightforward; proof of uniqueness is more challenging. Some proofs use the fact that if a prime number p divides the product of two natural numbers a and b, then p divides either a or b, a statement known as Euclid's lemma. Since multiplication on the integers is both commutative and associative, it does not matter in what way we write a number greater than 1 as the product of primes; it is common to write the (prime) factors in the order of smallest to largest.

Some natural extensions of the hypothesis of this theorem allow any non-zero integer to be expressed as the product of "prime numbers" and "invertibles". For example, 1 and −1 are allowed to be factors of such representations (although they are not considered to be prime). In this way, one can extend the Fundamental Theorem of Arithmetic to any Euclidean domain or principal ideal domain bearing in mind certain alterations to the hypothesis of the theorem. A ring in which the Fundamental Theorem of Arithmetic holds is called a unique factorization domain.

Many authors assume 1 to be a natural number that has no prime factorization. Thus Theorem 1 of Hardy & Wright (1979) takes the form, "Every positive integer, except 1, is a product of one or more primes," and Theorem 2 (their "Fundamental") asserts uniqueness. By convention, the number 1 is not itself prime, but since it is the product of no numbers, it is often convenient to include it in the theorem by the empty product rule. (See, for example, Calculating the gcd.)

Contents |

Applications

The fundamental theorem of arithmetic establishes the importance of prime numbers. Prime numbers are the basic building blocks of any positive integer, in the sense that each positive integer can be constructed from the product of primes with one unique construction. Finding the prime factorization of an integer allows derivation of all its divisors, both prime and non-prime. This property of uniqueness is powerful, as the factorization can be thought of as a key for a number. This is why it can be used to build powerful encryption techniques such as RSA.

For example, the above factorization of 6936 shows that any positive divisor of 6936 must have the form 2a × 3b × 17c, where a takes one of the 4 values in {0, 1, 2, 3}, where b takes one of the 2 values in {0, 1}, and where c takes one of the 3 values in {0, 1, 2}. Multiplying the numbers of independent options together produces a total of 4 × 2 × 3 = 24 positive divisors.

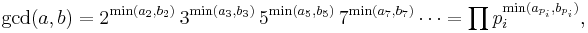

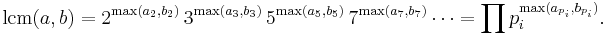

Once the prime factorizations of two numbers are known, their greatest common divisor and least common multiple can be found quickly. For instance, from the above it is shown that the greatest common divisor of 6936 and 1200 is 23 × 3 = 24. However, if the prime factorizations are not known, the use of the Euclidean algorithm generally requires much less calculation than factoring the two numbers.

The fundamental theorem ensures that additive and multiplicative arithmetic functions are completely determined by their values on the powers of prime numbers.

It may be important to note that Egyptians like Ahmes used earlier practical aspects of the factoring, such as the least common multiple, allowing a long tradition to develop, as formalized by Euclid, and rigorously proven by Carl Friedrich Gauss.

Although at first sight the theorem seems 'obvious', it does not hold in more general number systems, including many rings of algebraic integers. This was first pointed out by Ernst Kummer in 1843, in his work on Fermat's Last Theorem. The recognition of this failure is one of the earliest developments in algebraic number theory.

Euclid's proof

The proof consists of two steps. In the first step every number is shown to be a product of zero or more primes. In the second step, the proof shows that any two representations may be unified into a single representation.

Non-prime composite numbers

Proof by contradiction via minimal counterexample: Suppose there were positive integers which cannot be written as a product of primes. Then by the well-ordering principle there must be a smallest such number, n. Because of the empty-product convention above, n cannot be 1. Also, n cannot be a prime number, since any prime number is a product of a single prime: itself. So n must be a composite number. Thus

where both a and b are positive integers smaller than n. Since n is the smallest number which cannot be written as a product of primes, both a and b can be written as products of primes. But then

can be written as a product of primes as well, simply by combining the factorizations of a and b; but this contradicts our supposition. Hence, all positive integers can be written as a product of primes.

Proof of uniqueness

The key step in proving uniqueness is Euclid's proposition 30 of book 7 (known as Euclid's lemma), which states that, for any prime number p and any natural numbers a, b: if p divides ab then p divides a or p divides b.

This may be proved as follows:

- Suppose that a prime p divides ab (where a, b are natural numbers) but does not divide a. We must prove that p divides b.

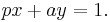

- Since p does not divide a, and p is prime, the greatest common divisor of p and a is

.

. - By Bézout's identity, it follows that for some integers x, y (possibly negative),

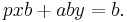

- Multiplying both sides by b,

- Since p divides

, p divides

, p divides

- Since p divides both summands on the left, p divides b.

A proof of the uniqueness of the prime factorization of a given integer proceeds as follows. Let s be the smallest natural number that can be written as (at least) two different products of prime numbers. Denote these two factorizations of s as p1···pm and q 1···qn, such that s = p1p2···pm = q 1q2···qn. Both q1 and q 2···qn must have unique prime factorizations (since both are smaller than s). By Euclid's proposition either p1 divides q1, or p1 divides q 2···qn. Therefore p1 = qj (for some j).[1] But by removing p1 and qj from the initial equivalence we have a smaller integer factorizable in two ways, contradicting our initial assumption. Therefore there can be no such s, and all natural numbers have a unique prime factorization.

Alternate proof of uniqueness

Assume that s is the least integer that can be written as (at least) two different products of prime numbers. Denote these two factorizations of s as p1···pm and q 1···qn, such that s = p1p2···pm = q1q2···qn.

No pi (with 1 ≤ i ≤ m) can be equal to any qj (with 1 ≤ j ≤ n), as there would otherwise be a smaller integer factorizable in two ways (by removing prime factors common in both products), violating the above assumption. Now it can be assumed without loss of generality that p1 is a prime factor smaller than any q j (with 1 ≤ j ≤ n). Note that  . Therefore,

. Therefore, and

and  divides

divides  . Since

. Since  is smaller than s, it has a unique factorization

is smaller than s, it has a unique factorization  . This is impossible.

. This is impossible.

Canonical representation of a positive integer

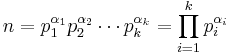

Since the prime factors of an integer need not be distinct, it follows from the Fundamental Theorem of Arithmetic that each integer n > 1 can be represented in exactly one way as a product of prime powers (1 corresponding to the empty product)

where p1 < p2 < ... < pk are primes and the αi are positive integers.

This representation is called the canonical representation[2] of n, or the standard form[3] of n.

E.g., 12 = 22·3, 1296 = 24·34, and 220 = 22·5·11.

If, in a given problem, only one number is represented in this way, we usually require αi to be positive for each i, as above. However, for notational convenience when two or more numbers are involved, we sometimes allow some of the exponents to be zero. If α1 = 0, for example, the prime p1 simply does not occur in the canonical representation of n. This device makes it possible to write the canonical representation of any two positive integers so that they appear to involve the same prime factors even though they may, in fact, fail to have any nontrivial common factor. For example, we could write 12 = 22·3·50 and 20 = 22·30·5. And one could even write 1 = 20·30·50.[4]

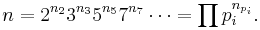

This can be taken a bit further: any integer can be uniquely represented as an infinite product taken over all the prime numbers,

where all but a finite number of the ni are zero. (1 corresponding to all ni being zero.) This representation is convenient for expressions like these for the product, gcd, and lcm:

Generalizations

The fundamental theorem of arithmetic generalizes to various contexts; for example in the context of ring theory, where the field of algebraic number theory develops. A ring is said to be a unique factorization domain if the Fundamental theorem of arithmetic (for non-zero elements) holds there. For example, any Euclidean domain or principal ideal domain is necessarily a unique factorization domain. Specifically, a field is trivially a unique factorization domain.

See also

- Divisor function

- Fundamental theorem of algebra

- Fundamental theorem of calculus

- Integer factorization

- Prime signature

- Unique factorization domain

Notes

- ^ If p1 divides q1 then, since both are prime, p1 = q1. If, on the other hand, p1 divides q 2···qn, then, since p1 and all qn are prime, and we know that q 2···qn has a unique prime factorization, then p1 must be among q 2···qn.

- ^ Long (1972, p. 45)

- ^ Pettofrezzo & Byrkit (1970, p. 55)

- ^ Long (1972, p. 45)

References

- Baker, Alan (1984), A Concise Introduction to the Theory of Numbers, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-28654-1

- Hardy, G. H.; Wright, E. M. (1979), An Introduction to the Theory of Numbers (fifth ed.), USA: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-853171-5

- Long, Calvin T. (1972), Elementary Introduction to Number Theory (2nd ed.), Lexington: D. C. Heath and Company.

- Pettofrezzo, Anthony J.; Byrkit, Donald R. (1970), Elements of Number Theory, Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Abnormal number" from MathWorld.

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Fundamental Theorem of Arithmetic" from MathWorld.

- A. Korni lowicz and P. Rudnicki. Fundamental theorem of arithmetic. Formalized Mathematics, 12(2):179–185, 2004.

External links

- GCD and the Fundamental Theorem of Arithmetic at cut-the-knot

- PlanetMath: Proof of fundamental theorem of arithmetic

- Fermat's Last Theorem Blog: Unique Factorization, A blog that covers the history of Fermat's Last Theorem from Diophantus of Alexandria to the proof by Andrew Wiles.

- "Fundamental Theorem of Arithmetic" by Hector Zenil, Wolfram Demonstrations Project, 2007.

|

|||||||||||