Frictional contact mechanics

| Continuum mechanics |

|---|

Contact mechanics is the study of the deformation of solids that touch each other at one or more points.[1][2] This can be divided into compressive and adhesive forces in the direction perpendicular to the interface, and frictional forces in the tangential direction. Frictional contact mechanics is the study of the deformation of bodies in the presence of frictional effects, whereas frictionless contact mechanics assumes the absence of such effects.

Frictional contact mechanics is concerned with a large range of different scales.

- At the macroscopic scale, it is applied for the investigation of the motion of contacting bodies (see Contact dynamics). For instance the bouncing of a rubber ball on a surface depends on the frictional interaction at the contact interface. Here the total force versus indentation and lateral displacement are of main concern.

- At the intermediate scale, one is interested in the local stresses, strains and deformations of the contacting bodies in and near the contact area. For instance to derive or validate contact models at the macroscopic scale, or to investigate wear and damage of the contacting bodies’ surfaces. Application areas of this scale are tire-pavement interaction, railway wheel-rail interaction, roller bearing analysis, etc.

- Finally, at the microscopic and nano-scales, contact mechanics is used to increase our understanding of tribological systems, e.g. investigate the origin of friction, and for the engineering of advanced devices like atomic force microscopes and MEMS devices.

This page is mainly concerned with the second scale: getting basic insight in the stresses and deformations in and near the contact patch, without paying too much attention to the detailed mechanisms by which they come about.

Contents |

History

Several famous scientists and engineers contributed to our understanding of friction.[3] They include Leonardo da Vinci, Guillaume Amontons, John Theophilus Desaguliers, Leonard Euler, and Charles-Augustin de Coulomb. Later, Nikolai Pavlovich Petrov, Osborne Reynolds and Stribeck supplemented this understanding with theories of lubrication.

Deformation of solid materials was investigated in the 17th and 18th centuries by Robert Hooke, Joseph Louis Lagrange, and in the 19th and 20th centuries by d’Alembert and Timoshenko. With respect to contact mechanics the classical contribution by Heinrich Hertz[4] stands out. Further the fundamental solutions by Boussinesq and Cerruti are of primary importance for the investigation of frictional contact problems in the (linearly) elastic regime.

Classical results for a true frictional contact problem concern the papers by F.W. Carter (1926) and H. Fromm (1927). They independently presented the creep-force relation for two cylinders in steady rolling conditions using Coulomb’s dry friction law.[5] These are applied to railway locomotive traction, and for understanding the hunting oscillation of railway vehicles. With respect to sliding, the classical solutions are due to C. Cattaneo (1938) and R.D. Mindlin (1949), who considered the tangential shifting of a cylinder on a plane (see below).[1]

In the 1950s interest in the rolling contact of railway wheels grew. In 1958 K.L. Johnson presented an approximate approach for the 3D frictional problem with Hertzian geometry, with either lateral or spin creepage. Among others he found that spin creepage, which is symmetric about the center of the contact patch, leads to a net lateral force in rolling conditions. This is due to the fore-aft differences in the distribution of tractions in the contact patch.

In 1967 Joost Kalker published his milestone PhD thesis on the linear theory for rolling contact.[6] This theory is exact for the situation of an infinite friction coefficient in which case the slip area vanishes, and is approximative for non-vanishing creepages. It does assume Coulomb’s friction law, which more or less requires (scrupulously) clean surfaces. This theory is for massive bodies such as the railway wheel-rail contact. With respect to road-tire interaction, an important contribution concerns the so-called magic tire formula by Hans Pacejka.[7]

In the 1970s many numerical models were devised. Particularly variational approaches, such as those relying on Duvaut and Lion’s existence and uniqueness theories. Over time, these grew into finite element approaches for contact problems with general material models and geometries, and into half-space based approaches for so-called smooth-edged contact problems for linearly elastic materials. Models of the first category were presented by Laursen[8] and by Wriggers.[9] An example of the latter category is Kalker’s CONTACT model.[10]

A drawback of the well-founded variational approaches is their large computation times. Therefore many different approximate approaches were devised as well. Several well-known approximate theories for the rolling contact problem are Kalker’s FASTSIM approach, the Shen-Hedrick-Elkins formula, and Polach’s approach.

More information on the history of the wheel/rail contact problem is provided in Knothe's paper.[5] Further Johnson collected in his book a tremendous amount of information on contact mechanics and related subjects.[1] With respect to rolling contact mechanics an overview of various theories is presented by Kalker as well.[10] Finally the proceedings of a CISM course are of interest, which provide an introduction to more advanced aspects of rolling contact theory.[11]

Problem formulation

Central in the analysis of frictional contact problems is the understanding that the stresses at the surface of each body are spatially varying. Consequently the strains and deformations of the bodies are varying with position too. And the motion of particles of the contacting bodies can be different at different locations: in part of the contact patch particles of the opposing bodies may adhere (stick) to each other, whereas in other parts of the contact patch relative movement occurs. This local relative sliding is called micro-slip.

This subdivision of the contact area into stick (adhesion) and slip areas manifests itself a.o. in fretting wear. Note that wear occurs only where power is dissipated, which requires stress and local relative displacement (slip) between the two surfaces.

The size and shape of the contact patch itself and of its adhesion and slip areas are generally unknown in advance. If these were known, then the elastic fields in the two bodies could be solved independently from each other and the problem would not be a contact problem anymore.

Three different components can be distinguished in a contact problem.

- First of all, there is the reaction (deformation) of the separate bodies to loads applied on their surfaces. This is the subject of general continuum mechanics. It depends largely on the geometry of the bodies and on their (constitutive) material behavior (e.g. elastic vs. plastic response, homogeneous vs. layered structure etc.).

- Secondly, there is the overall motion of the bodies relative to each other. For instance the bodies can be at rest (statics) or approaching each other quickly (impact), and can be shifted (sliding) or rotated (rolling) over each other. These overall motions are generally studied in classical mechanics, see for instance multibody dynamics.

- Finally there are the processes at the contact interface: compression and adhesion in the direction perpendicular to the interface, and friction and micro-slip in the tangential directions.

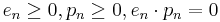

The last aspect is the primary concern of contact mechanics. It is described in terms of so-called “contact conditions”. For the direction perpendicular to the interface, the normal contact problem, adhesion effects are usually small (at larger spatial scales) and the following conditions are typically employed:

- The gap

between the two surfaces must be zero (contact) or strictly positive (

between the two surfaces must be zero (contact) or strictly positive ( , separation);

, separation); - The normal stress

acting on each body is zero (separation) or compressive (

acting on each body is zero (separation) or compressive ( in contact).

in contact).

Mathematically:  . Here

. Here  are functions that vary with the position along the bodies' surfaces.

are functions that vary with the position along the bodies' surfaces.

In the tangential directions the following conditions are often used:

- The local (tangential) shear stress

(if the normal direction is parallel to the

(if the normal direction is parallel to the  -axis) cannot exceed a certain position-dependent maximum, the so-called traction bound

-axis) cannot exceed a certain position-dependent maximum, the so-called traction bound  ;

; - Where the magnitude of tangential traction falls below the traction bound

, the opposing surfaces adhere together and micro-slip vanishes,

, the opposing surfaces adhere together and micro-slip vanishes,  ;

; - Micro-slip occurs where the tangential tractions are at the traction bound; the direction of the tangential traction is then opposite to the direction of micro-slip

.

.

The precise form of the traction bound is the so-called local friction law. For this Coulomb's (global) friction law is often applied locally:  , with

, with  the friction coefficient. More detailed formulae are also possible, for instance with

the friction coefficient. More detailed formulae are also possible, for instance with  depending on temperature

depending on temperature  , local sliding velocity

, local sliding velocity  , etc.

, etc.

Solutions for static cases

Rope on a bollard, the capstan equation

Consider a rope where equal forces (e.g.  ) are exerted on both sides. By this the rope is stretched a bit and an internal tension

) are exerted on both sides. By this the rope is stretched a bit and an internal tension  is induced (

is induced ( on every position along the rope). The rope is wrapped around a fixed item such as a bollard; it is bent and makes contact to the item's surface over a contact angle (e.g.

on every position along the rope). The rope is wrapped around a fixed item such as a bollard; it is bent and makes contact to the item's surface over a contact angle (e.g.  ). Normal pressure comes into being between the rope and bollard, but no friction occurs yet. Next the force on one side of the bollard is increased to a higher value (e.g.

). Normal pressure comes into being between the rope and bollard, but no friction occurs yet. Next the force on one side of the bollard is increased to a higher value (e.g.  ). This does cause frictional shear stresses in the contact area. In the final situation the bollard exercises a friction force on the rope such that a static situation occurs.

). This does cause frictional shear stresses in the contact area. In the final situation the bollard exercises a friction force on the rope such that a static situation occurs.

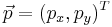

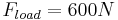

The tension distribution in the rope in this final situation is described by the capstan equation, with solution:

The tension increases from  on the slack side (

on the slack side ( ) to

) to  on the high side

on the high side  . When viewed from the high side, the tension drops exponentially, until it reaches the lower load at

. When viewed from the high side, the tension drops exponentially, until it reaches the lower load at  . From there on it is constant at this value. The transition point

. From there on it is constant at this value. The transition point  is determined by the ratio of the two loads and the friction coefficient. Here the tensions

is determined by the ratio of the two loads and the friction coefficient. Here the tensions  are in Newtons and the angles

are in Newtons and the angles  in radians.

in radians.

The tension  in the rope in the final situation is increased with respect to the initial state. Therefore the rope is elongated a bit. This means that not all surface particles of the rope can have held their initial position on the bollard surface. During the loading process, the rope slipped a little bit along the bollard surface in the slip area

in the rope in the final situation is increased with respect to the initial state. Therefore the rope is elongated a bit. This means that not all surface particles of the rope can have held their initial position on the bollard surface. During the loading process, the rope slipped a little bit along the bollard surface in the slip area ![\phi\in[\phi_1,\phi_{load}]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/611e4eda0b79fa6420ce0c09243bc929.png) . This slip is precisely large enough to get to the elongation that occurs in the final state. Note that there is no slipping going on in the final state; the term slip area refers to the slippage that occurred during the loading process. Note further that the location of the slip area depends on the initial state and the loading process. If the initial tension is

. This slip is precisely large enough to get to the elongation that occurs in the final state. Note that there is no slipping going on in the final state; the term slip area refers to the slippage that occurred during the loading process. Note further that the location of the slip area depends on the initial state and the loading process. If the initial tension is  and the tension is reduced to

and the tension is reduced to  at the slack side, then the slip area occurs at the slack side of the contact area. For initial tensions between

at the slack side, then the slip area occurs at the slack side of the contact area. For initial tensions between  and

and  , there can be slip areas on both sides with a stick area in between.

, there can be slip areas on both sides with a stick area in between.

Sphere on a plane, the (3D) Cattaneo problem

Consider a sphere that is pressed onto a plane (half space) and then shifted over the plane's surface. If the sphere and plane are idealised as rigid bodies, then contact would occur in just a single point, and the sphere would not move until the tangential force that is applied reaches the maximum friction force. Then it starts sliding over the surface until the applied force is reduced again.

How different is the situation in reality, if we include elastic effects. If an elastic sphere is pressed onto an elastic plane of the same material then both bodies deform, a circular contact area comes into being, and a (Hertzian) normal pressure distribution arises. Also, the center of the sphere is moved down a bit by a distance  that is called the approach, which is also the maximum penetration of the undeformed surfaces.

that is called the approach, which is also the maximum penetration of the undeformed surfaces.

Now consider that a tangential force is applied that is lower than the Coulomb friction bound. The center of the sphere will then be moved sideways by a small distance that is called the shift. A static equilibrium is obtained in which elastic deformations occur as well as frictional shear stresses in the contact interface. In this case, if the tangential force is reduced then the elastic deformations and shear stresses reduce as well. The sphere largely shifts back to its original position, except for frictional losses that arise due to local slip in the contact patch.

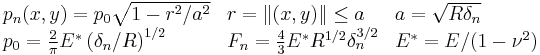

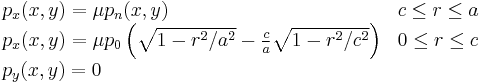

This contact problem was solved approximately by Cattaneo using an analytical approach. The stress distribution in the equilibrium state consists of two parts:

In the central, sticking region  , the surface particles of the plane displace over

, the surface particles of the plane displace over  to the right whereas the surface particles of the sphere displace over

to the right whereas the surface particles of the sphere displace over  to the left. Even though the sphere as a whole moves over

to the left. Even though the sphere as a whole moves over  relative to the plane, these surface particles did not move relative to each other. In the outer annulus

relative to the plane, these surface particles did not move relative to each other. In the outer annulus  , the surface particles did move relative to each other. Their local shift is obtained as

, the surface particles did move relative to each other. Their local shift is obtained as

This shift  is precisely as large such that a static equilibrium is obtained with shear stresses at the traction bound in this so-called slip area.

is precisely as large such that a static equilibrium is obtained with shear stresses at the traction bound in this so-called slip area.

During the tangential loading of the sphere, partial sliding occurs. The contact area is thus divided into a slip area where the surfaces move relative to each other and a stick area where they do not. In the equilibrium state no more sliding is going on.

Solutions for dynamic sliding problems

The solution of a contact problem, that is, the elastic field in the bodies' interiors together with the state at the interface (division of stick and slip zones, normal and shear stress distributions), depends on the history of the contact. This can be seen by extension of the Cattaneo problem described above.

- In the Cattaneo problem, the sphere is first pressed onto the plane and then shifted tangentially. This yields partial slip as described above.

- If the sphere is first shifted tangentially and then pressed onto the plane, then there is no tangential displacement difference between the opposing surfaces and consequently there is no tangential stress in the contact interface.

- If the approach in normal direction and tangential shift are increased simultaneously then a situation can be achieved with tangential stress but without local slip.[2]

This demonstrates that the state in the contact interface is not only dependent on the relative positions of the two bodies, but also on their motion history. Another example of this occurs if the sphere is shifted back to its original position. Initially there was no tangential stress in the contact interface. After the initial shift micro-slip has occurred. This micro-slip is not entirely undone by shifting back, such that eventually tangential stresses remain in the interface in what on an overall level looks like the same as the original configuration.

Solution of rolling contact problems

Rolling contact problems are dynamic problems in which the contacting bodies are continuously moving with respect to each other. A difference to dynamic sliding contact problems is that there is more variety in the state of different surface particles. Whereas the contact patch in a sliding problem continuously consists of more or less the same particles, in a rolling contact problem particles enter and leave the contact patch incessantly. Moreover, in a sliding problem the surface particles in the contact patch are all subjected to more or less the same tangential shift everywhere, whereas in a rolling problem the surface particles are stressed in rather different ways. They are free of stress when entering the contact patch, then stick to a particle of the opposing surface, are strained by the overall motion difference between the two bodies, until the local traction bound is exceeded and local slip sets in. This process is in different stages for different parts of the contact area.

If the overall motion of the bodies is constant, then an overall steady state may be attained. Here the state of each surface particle is varying in time, but the overall distribution can be constant. This is formalised by using a coordinate system that is moving along with the contact patch.

Half-space based approaches

When considering contact problems at the intermediate spatial scales, the small-scale material inhomogeneities and surface roughness are ignored. The bodies are considered as consisting of smooth surfaces and homogeneous materials. A continuum approach is taken where the stresses, strains and displacements are described by (piecewise) continuous functions.

The half-space approach is an elegant solution strategy for so-called "smooth-edged" or "concentrated" contact problems.

- If a massive elastic body is loaded on a small section of its surface, then the elastic stresses attenuate proportional to

and the elastic displacements by

and the elastic displacements by  when one moves away from this surface area.

when one moves away from this surface area. - If a body has no sharp corners in or near the contact region, then its response to a surface load may be approximated well by the response of an elastic half-space (e.g. all points

with

with  ).

). - The elastic half-space problem is solved analytically, see the Boussinesq-Cerruti solution.

- Due to the linearity of this approach, multiple partial solutions may be super-imposed.

Using the fundamental solution for the half-space, the full 3D contact problem is reduced to a 2D problem for the bodies' bounding surfaces.

A further simplification occurs if the two bodies are “geometrically and elastically alike”. In general, stress inside a body in one direction induces displacements in perpendicular directions too. Consequently there is an interaction between the normal stress and tangential displacements in the contact problem, and an interaction between the tangential stress and normal displacements. But if the normal stress in the contact interface induces the same tangential displacements in both contacting bodies, then there is no relative tangential displacement of the two surfaces. In that case, the normal and tangential contact problems are decoupled. If this is the case then the two bodies are called quasi-identical. This happens for instance if the bodies are mirror-symmetric with respect to the contact plane and have the same elastic constants.

Classical solutions based on the half-space approach are:

- Hertz solved the contact problem in the absence of friction, for a simple geometry (curved surfaces with constant radii of curvature).

- Carter and Fromm considered the rolling contact between two cylinders with parallel axes. (Relatively) far away from the ends of the cylinders a situation of plane strain occurs and the problem is 2-dimensional. A complete analytical solution is provided for the tangential traction.

- Cattaneo considered the compression and shifting of two spheres, as described above. Note that this analytical solution is approximate. In reality small tangential tractions

occur which are ignored.

occur which are ignored.

See also

- Bearings

- (Linear) elasticity

- Metallurgy

- Multibody system

- Plasticity

- Solid mechanics

- Vehicle dynamics

References

- ^ a b c Johnson, K.L. (1985). Contact Mechanics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ a b Popov, V.L. (2010). Contact Mechanics and Friction. Physical Principles and Applications. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

- ^ "Introduction to Tribology – Friction". http://depts.washington.edu/nanolab/ChemE554/Summaries%20ChemE%20554/Introduction%20Tribology.htm. Retrieved 2008-12-21.

- ^ Hertz, Heinrich (1882). "Contact between solid elastic bodies". Journ. Für reine und angewandte Math. 92.

- ^ a b Knothe, K. (2008). "History of wheel/rail contact mechanics: from Redtenbacher to Kalker". Vehicle System Dynamics 46 (1-2): 9–26.

- ^ Kalker, Joost J. (1967). On the rolling contact of two elastic bodies in the presence of dry friction. Delft University of Technology.

- ^ Pacejka, Hans (2002). Tire and Vehicle Dynamics. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann.

- ^ Laursen, T.A., 2002, Computational Contact and Impact Mechanics, Fundamentals of Modeling Interfacial Phenomena in Nonlinear Finite Element Analysis, Springer, Berlin

- ^ Wriggers, P., 2006, Computational Contact Mechanics, 2nd ed., Springer, Heidelberg

- ^ a b Kalker, J.J., 1990, Three-Dimensional Elastic Bodies in Rolling Contact, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht

- ^ B. Jacobsen and J.J. Kalker, ed (2000). Rolling Contact Phenomena. Wien New York: Springer-Verlag.

![\begin{matrix} T(\phi) = T_{hold}, & \phi\in[\phi_{hold},\phi_{intf}] \\

T(\phi) = T_{load} \exp(-\mu\phi), & \phi\in[\phi_{intf},\phi_{load}] \\

\phi_{intf} = \log(T_{load}/T_{hold}) / \mu &

\end{matrix}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/3325ff477a6e633bcc4bfcdd7a862337.png)