Forward exchange rate

The forward exchange rate (also referred to as forward rate or forward price) is the rate at which a bank is willing to exchange one currency for another at some specified future date.[1] The forward exchange rate is a type of forward price. It is the exchange rate negotiated today between a bank and a client upon entering into a forward contract agreeing to buy or sell some amount of foreign currency at a future date.[2][3] The forward exchange rate is determined by the relationship among the spot exchange rate and differences in interest rates between two countries. Forward exchange rates have important theoretical implications in forecasting future spot exchange rates.

Multinational corporations often use the forward market to hedge future payables or receivables denominated in a foreign currency against foreign exchange risk by using a forward contract to lock in a forward exchange rate. Hedging with forward contracts is typically used for larger transactions, while futures contracts are used for smaller transactions. This is due to the customization afforded to banks by forward contracts traded over-the-counter, versus the standardization of futures contracts which are traded on an exchange.[1] Banks typically quote forward rates for major currencies in maturities of 1, 3, 6, 9, or 12 months, however in some cases quotations for greater maturities are available up to 5 or 10 years.[2]

Contents |

Forward exchange rate determinants

Covered interest rate parity offers an explanation of what determines forward exchange rates. The forward exchange rate is determined by three known variables: the spot exchange rate, the domestic interest rate, and the foreign interest rate. This effectively means that the forward rate is the price of a forward contract, which derives its value from the pricing of spot contracts and the addition of information on available interest rates.[4]

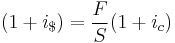

The following equation represents covered interest rate parity, a no-arbitrage condition under which investors eliminate exposure to exchange rate risk (unanticipated changes in exchange rates) with the use of a forward contract - the exchange rate risk is effectively covered. The reason for the no-arbitrage condition is that the dollar return on dollar deposits, 1+i$, is set equal to the dollar return on euro deposits, F/S(1+ic). If these two returns weren't equal, there would be a potential arbitrage opportunity in which an investor could borrow currency in the country with the lower interest rate, convert to the foreign currency at today's spot exchange rate, and invest in the foreign country with the higher interest rate. Investors will be indifferent to the interest rates on deposits in these countries due to the equilibrium resulting from the forward exchange rate.[4]

where

- F is the forward exchange rate

- S is the current spot exchange rate

- i$ is the interest rate in the US

- ic is the interest rate in a foreign country or currency area (for this example, it is the interest rate available in the Eurozone)

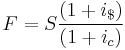

This equation can be arranged such that it solves for the forward rate:

The equilibrium that results from the relationship between forward and spot exchange rates within the context of covered interest rate parity is responsible for eliminating or correcting for market inefficiencies that would create potential for arbitrage profits. As such, arbitrage opportunities are fleeting. In order for this equilibrium to hold under differences in interest rates between two countries, the forward exchange rate must generally differ from the spot exchange rate, such that a no-arbitrage condition is sustained. Therefore, the forward rate is said to contain a premium or discount, reflecting the interest rate differential between two countries. The following equations demonstrate how the forward premium or discount is calculated.[1][2]

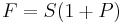

The forward exchange rate differs by a premium or discount of the spot exchange rate:

where

- P is the premium (if positive) or discount (if negative)

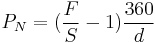

The equation can be rearranged as follows to solve for the forward premium/discount:

In practice, forward premiums and discounts are quoted as annualized percentage deviations from the spot exchange rate, in which case it is necessary to account for the number of days to delivery as in the following example.[2]

where

- N represents the maturity of a given forward exchange rate quote

- d represents the number of days to delivery

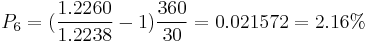

For example, to calculate the 6-month forward premium or discount for the euro versus the dollar deliverable in 30 days, given a spot rate quote of 1.2238 $/€ and a 6-month forward rate quote of 1.2260 $/€:

The resulting 0.021572 is positive, so one would say that the euro is trading at a 0.021572 or 2.16% premium against the dollar for delivery in 30 days. Conversely, if one were to work this example in euro terms rather than dollar terms, the perspective would be reversed and one would say that the dollar is trading at a discount against the euro.

Forecasting future spot exchange rates

Unbiasedness hypothesis

The unbiasedness hypothesis states that given conditions of rational expectations and risk neutrality, the forward exchange rate is an unbiased predictor of the expected future spot exchange rate. Without introducing a foreign exchange risk premium (due to the assumption of risk neutrality), the following equation illustrates the unbiasedness hypothesis.[3][5][6][7]

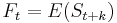

where

is the forward exchange rate at time t

is the forward exchange rate at time t is the expected future spot exchange rate at time t + k

is the expected future spot exchange rate at time t + k- k is the number of periods into the future from time t

The unbiasedness hypothesis is a well-recognized puzzle among finance researchers. Empirical evidence for cointegration between the forward rate and the future spot rate is mixed.[5][8] Researchers have published papers demonstrating empirical failure of the hypothesis by conducting regression analyses of the realized changes in spot exchange rates on forward premiums and finding negative slope coefficients. These researchers offer numerous rationales for such failure. One rationale centers around the relaxation of risk neutrality, while still assuming rational expectations, such that a foreign exchange risk premium may exist that can account for differences between the forward rate and the expected future spot rate.[9]

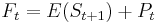

The following equation represents the forward rate as being equal to an expected future spot rate and a risk premium (not to be confused with a forward premium):[10]

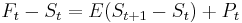

The current spot rate can be introduced so that the equation solves for the forward-spot differential (the difference between the forward rate and the current spot rate):

Eugene Fama concluded that large positive correlations of the difference between the forward exchange rate and the current spot exchange rate signal variations over time in the premium component of the forward-spot differential  or in the forecast of the expected change in the spot exchange rate. Fama suggested that slope coefficients in the regressions of the difference between the forward rate and the future spot rate

or in the forecast of the expected change in the spot exchange rate. Fama suggested that slope coefficients in the regressions of the difference between the forward rate and the future spot rate  , and the expected change in the spot rate

, and the expected change in the spot rate  , on the forward-spot differential

, on the forward-spot differential  which are different from 0 imply variations over time in both components of the forward-spot differential: the premium and the expected change in the spot rate.[10] Fama's findings were sought to be empirically validated by a significant body of research, ultimately finding that large variance in expected changes in the spot rate could only be accounted for by risk aversion coefficients that were deemed "unacceptably high."[7][9]

which are different from 0 imply variations over time in both components of the forward-spot differential: the premium and the expected change in the spot rate.[10] Fama's findings were sought to be empirically validated by a significant body of research, ultimately finding that large variance in expected changes in the spot rate could only be accounted for by risk aversion coefficients that were deemed "unacceptably high."[7][9]

Other rationales for the failure of the forward rate unbiasedness hypothesis include considering the conditional bias to be an exogenous variable explained by a policy aimed at smoothing interest rates and stabilizing exchange rates, or considering that an economy allowing for discrete changes could facilitate excess returns in the forward market. Some researchers have contested empirical failures of the hypothesis and have sought to explain conflicting evidence as resulting from contaminated data and even inappropriate selections of the time length of forward contracts.[9]

See also

References

- ^ a b c Madura, Jeff (2007). International Financial Management: Abridged 8th Edition. Mason, OH: Thomson South-Western. ISBN 0-324-36563-2.

- ^ a b c d Eun, Cheol S.; Resnick, Bruce G. (2011). International Financial Management, 6th Edition. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill/Irwin. ISBN 978-0-07-803465-7.

- ^ a b Levi, Maurice D. (2005). International Finance, 4th Edition. New York, NY: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-41-530900-4.

- ^ a b Feenstra, Robert C.; Taylor, Alan M. (2008). International Macroeconomics. New York, NY: Worth Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4292-0691-4.

- ^ a b Delcoure, Natalya; Barkoulas, John; Baum, Christopher F.; Chakraborty, Atreya (2003). "The Forward Rate Unbiasedness Hypothesis Reexamined: Evidence from a New Test". Global Finance Journal 14 (1): 83–93. doi:10.1016/S1044-0283(03)00006-1. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1044028303000061. Retrieved 2011-06-21.

- ^ Ho, Tsung-Wu (2003). "A re-examination of the unbiasedness forward rate hypothesis using dynamic SUR model". The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance 43 (3): 542–559. doi:10.1016/S1062-9769(02)00171-0. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1062976902001710. Retrieved 2011-06-23.

- ^ a b Sosvilla-Rivero, Simón; Park, Young B. (1992). "Further tests on the forward exchange rate unbiasedness hypothesis". Economics Letters 40 (3): 325–331. doi:10.1016/0165-1765(92)90013-O. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/016517659290013O. Retrieved 2011-06-27.

- ^ Moffett, Michael H.; Stonehill, Arthur I.; Eiteman, David K. (2009). Fundamentals of Multinational Finance, 3rd Edition. Boston, MA: Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0-32-154164-2.

- ^ a b c Diamandis, Panayiotis F.; Georgoutsos, Dimitris A.; Kouretas, Georgios P. (2008). "Testing the forward rate unbiasedness hypothesis during the 1920s". International Financial Markets, Institutions & Money 18 (4): 358–373. doi:10.1016/j.intfin.2007.04.003. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1042443107000212. Retrieved 2011-06-23.

- ^ a b Fama, Eugene F. (1984). "Forward and spot exchange rates". Journal of Monetary Economics 14 (3): 319–338. doi:10.1016/0304-3932(84)90046-1. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0304393284900461. Retrieved 2011-06-20.