Flag of convenience

The term flag of convenience describes the business practice of registering a merchant ship in a sovereign state different from that of the ship's owners, and flying that state's civil ensign on the ship. Ships are registered under flags of convenience to reduce operating costs or avoid the regulations of the owner's country. The closely related term open registry is used to describe an organization that will register ships owned by foreign entities.

The term "flag of convenience" has been in use since the 1950s and refers to the civil ensign a ship flies to indicate its country of registration or flag state. A ship operates under the laws of its flag state, and these laws are used if the ship is involved in an admiralty case.

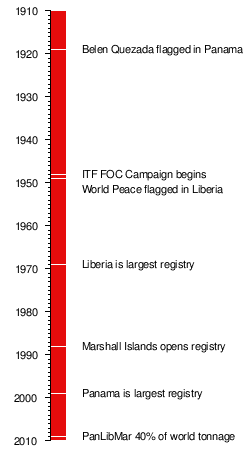

The modern practice of flagging ships in foreign countries began in the 1920s in the United States, when shipowners frustrated by increased regulations and rising labor costs began to register their ships to Panama. The use of flags of convenience steadily increased, and in 1968, Liberia grew to surpass the United Kingdom as the world's largest shipping register. As of 2009[update], more than half of the world’s merchant ships are registered under flags of convenience, and the Panamanian, Liberian, and Marshallese flags of convenience account for almost 40% of the entire world fleet, in terms of deadweight tonnage.

Flag-of-convenience registries are often criticized. As of 2009[update], thirteen flag states have been found by international shipping organizations to have substandard regulations. A basis for many criticisms is that the flag-of-convenience system allows shipowners to be legally anonymous and difficult to prosecute in civil and criminal actions. Ships with flags of convenience have been found engaging in crime and terrorism, frequently offer substandard working conditions, and negatively impact the environment, primarily through illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing. As of 2009[update], ships of thirteen flags of convenience are targeted for special enforcement by countries that they visit. Supporters of the practice, however, point to economic and regulatory advantages, and increased freedom in choosing employees from an international labor pool.

Contents |

Background

International law requires that every merchant ship be registered in a country.[2] This country in which a ship is registered is called its flag state,[3] and the flag state gives the ship the right to fly its civil ensign.[4] A ship's flag state exercises regulatory control over the vessel and is required to inspect it regularly, certify the ship's equipment and crew, and issue safety and pollution prevention documents. A ship operates under the laws of its flag state, and these laws are used if the ship is involved in an admiralty case.[5] The organization which actually registers the ship is known as its registry. Registries may be governmental or private agencies. In some cases, such as the United States' Alternative Compliance Program, the registry can assign a third party to administer inspections.[6]

The reasons for choosing an open register are varied and include tax avoidance,[7] the ability to avoid national labor and environmental regulations,[7][8] and the ability to hire crews from lower-wage countries.[7][9] National or closed registries typically require a ship be owned and constructed by national interests, and at least partially crewed by its citizens. Conversely, open registries frequently offer on-line registration with few questions asked.[10][11] The use of flags of convenience lowers registration and maintenance costs, which in turn reduces overall transportation costs. The accumulated advantages can be significant, for example in 1999, 28 of Sea-Land's fleet of 63 ships were foreign flagged, saving the company up to 3.5 million dollars per ship every year.[7]

The environmental disaster caused by the 1978 sinking of the MV Amoco Cadiz, which flew the Liberian flag of convenience, spurred the creation of a new type of maritime enforcement.[12] Resulting from "strong political and public outcry" over the Cadiz sinking, fourteen European nations signed the 1982 "Paris Memorandum of Understanding on Port State Control" or Paris MOU.[12] Under port state control, ships in international trade became subject to inspection by the states they visit. In addition to shipboard living and working conditions, these inspections cover items concerning the safety of life at sea and the prevention of pollution by ships.[12] In cases when a port state inspection uncovers problems with a ship, the port state may take actions including detaining the ship.[13] In 2008, member states of the Paris MOU conducted 14,322 inspections with deficiencies, which resulted in vessels being detained 1,220 times that year.[14] Member states of the Tokyo Memorandum of Understanding conducted 13,298 ship inspections in 2009, recording 86,820 deficiencies which resulted in 1,336 detentions.[15]

The principle that there be a "genuine link" between a ship's owners and its flag state dates back to 1958, when Article 5(1) of the Geneva Convention on the High Seas also required that "the state must effectively exercise its jurisdiction and control in administrative, technical and social matters over ships flying its flag."[16] The principle was repeated in Article 91 of the 1982 treaty called the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea and often referred to as UNCLOS.[2] In 1986, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development attempted to solidify the genuine link concept in the United Nations Convention for Registration of Ships.[17] The Convention for Registration of Ships would require that a flag state be linked to its ships either by having an economic stake in the ownership of its ships or by providing mariners to crew the ships.[17] To come into force, the 1986 treaty requires 40 signatories whose combined tonnage exceeds 25% of the world total.[17] As of 2006[update], only 14 countries have signed the treaty.[17]

History

Merchant ships have used false flags as a tactic to evade enemy warships since antiquity, and examples can be found from as early as the Roman era through the Middle Ages.[18] More recently, this technique was used by the British during the Napoleonic Wars and the United States during the War of 1812.[19] During the mid-19th century, slave ships flew various flags to avoid being searched by British anti-slavery fleets.[20] However, the modern practice of registering ships in foreign countries to gain economic advantage originated in the United States in the era of World War I, and the term flag of convenience came into use in the 1950s.[21]

Between 1915 and 1922, several laws were passed in the United States to strengthen the United States Merchant Marine and provide safeguards for its mariners.[22] During this period, U.S.-flagged ships became subject to regular inspections undertaken by the American Bureau of Shipping.[22] This was also the time of Robert LaFollette's Seamen's Act of 1915, which has been described as the "Magna Carta of sailors' rights."[23] The Seamen's Act regulated mariners' working hours, their payment, and established baseline requirements for shipboard food.[23] It also reduced penalties for disobedience and abolished the practice of imprisoning sailors for the offense of desertion.[23] Another aspect of the Seamen's Act was enforcement of safety standards, with requirements on lifeboats, the number of qualified able seamen on board, and that officers and seamen be able to speak the same language.[23]

These laws put U.S.-flagged vessels at an economic disadvantage against countries lacking such safeguards.[22] By moving their ships to the Panamanian flag, owners could avoid providing these protections.[22] The Belen Quezada, the first foreign ship flagged in the Panamanian registry, was employed in running illegal alcohol between Canada and the United States during Prohibition.[24] In addition to sidestepping the Seamen's Act, Panamanian-flagged ships in this early period paid sailors on the Japanese wage scale, which was much lower than that of western merchant powers.[24]

The Liberian open registry was the brainchild of Edward Stettinius, who had been Franklin D. Roosevelt's Secretary of State during World War II.[25] Stettinius created a corporate structure that included The Liberia Corporation, a joint-venture with the government of Liberia.[25] The corporation was structured so that one-fourth of its revenue would go to the Liberian government, another 10% went to fund social programs in Liberia, and the remainder returned to Stettinius' corporation.[25] The Liberian registry was created at a time when Panama's registry was becoming less attractive for several reasons including its unpopularity with the U.S. labor movement and European shipping concerns, political unrest in Panama, and increases in its fees and regulations.[25]

On 11 March 1949, Greek shipping magnate Stavros Niarchos registered the first ship under the Liberian flag of convenience, the World Peace. When Stettinius died in 1949, ownership of the registry passed to the International Bank of Washington, led by General George Olmsted.[26] Within 18 years, Liberia grew to surpass the United Kingdom as the world's largest register.[26]

Due to Liberia's 1989 and 1999 civil wars, its registry eventually fell second to Panama's flag of convenience, but maritime funds continued to supply 70% of its total government revenue.[26] After the civil war of 1990, Liberia joined with the Republic of the Marshall Islands to develop a new maritime and corporate program.[26] The resulting company, International Registries, was formed as a parent company, and in 1993 was bought out by its management.[26] After taking over the Liberian government, Americo-Liberian warlord Charles Taylor signed a new registry contract with the Liberian International Ship and Corporate Registry, commonly known as LISCR. LISCR was one of the few legal sources of income for Taylor's regime.[26] Taylor is now on trial at the International Criminal Court in The Hague on 11 counts of war crimes, crimes against humanity, and other serious violations of international humanitarian law.[27]

As of 2009[update], the Panamanian, Liberian, and Marshallese flags of convenience account for almost 40% of the entire world fleet, in terms of deadweight tonnage[28] That same year, the top ten flags of convenience registered 55% of the world's deadweight tonnage, including 61% of bulk carriers and 56% of oil tankers.[28]

Extent of use

The International Transport Workers' Federation (ITF) maintains a list of 32 registries it considers to be FOC registries.[30] In developing the list, the ITF considers "ability and willingness of the flag state to enforce international minimum social standards on its vessels,"[29] the "degree of ratification and enforcement of ILO Conventions and Recommendations,"[29] and "safety and environmental record."[29] As of 2010[update] the list includes Antigua and Barbuda, the Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Bermuda, Bolivia, Burma, Cambodia, the Cayman Island, Comoros, Cyprus, Equatorial Guinea, Georgia, Gibraltar, Honduras, Jamaica, Lebanon, Liberia, Malta, the Marshall Islands, Mauritius, Mongolia, Netherlands Antilles, North Korea, Panama, Sao Tome and Príncipe, St Vincent, Sri Lanka, Tonga, Vanuatu, and the French and German International Ship Registers.[30]

As of 2009[update], Panama, Liberia and the Marshall Islands are the world’s three largest registries in terms of deadweight tonnage (DWT).[28] These three organizations registered 11,636 ships of 1,000 DWT and above, for a total of 468,405,000 DWT: more than 39% of the world's shipbourne carrying capacity.[28] Panama dominates the scene with over 8,065 ships accounting for almost 23% of the world's DWT.[28] Of the three, the Marshall Islands (with 1,265 registered ships) had the greatest rate of DWT increase in 2009, increasing its tonnage by almost 15%.[28]

The Bahamian flag ranks sixth worldwide, behind the Hong Kong and Greek registries, but is similar in size to the Marshallese flag of convenience, with about 200 more ships but a carrying capacity about 6,000,000 DWT lower.[28] Malta, at the ninth position worldwide, had about 100 more ships than the Bahamas, with a capacity of 50,666,000 DWT, representing 4% of the world fleet with 12% growth that year.[28]

At the eleventh position, Cyprus registered 1,016 ships in 2009, 2.6% of world tonnage.[28] The remaining top 11 flags of convenience are Antigua and Barbuda (#20), Bermuda (#22), Saint Vincent and the Grenadines (#26), and the French International Ship Register (FIS) at number #27.[28] Bermuda and the FIS have fewer than 200 ships apiece, but they are large: the average Bermudan ship is 67,310 DWT and the average FIS ship is at 42,524 DWT.[28] (By way of reference, the average capacity of ships in the U.S. and U.K. registers is 1,851 DWT and 9,517 DWT respectively.[28]) The registries of Antigua and Barbuda and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines both have over 1,000 ships with average capacity of 10,423 DWT and 7,334 DWT respectively.[28]

The 21 other flags of convenience listed by the ITF each account for less than 1% of the world's DWT.[28] As of 2008[update], more than half of the world’s merchant ships (measured by tonnage) are registered under flags of convenience.[31]

Criticism

There are a number of common threads found in criticisms of the flag of convenience system. One is that these flag states have insufficient regulations and that those regulations they do have are poorly enforced. Another is that, in many cases, the flag state cannot identify a shipowner, much less hold the owner civilly or criminally responsible for a ship's actions. As a result of this lack of flag state control, flags of convenience are criticized on grounds of providing an environment for conducting criminal activities, supporting terrorism, providing poor working conditions for seafarers, and having an adverse effect on the environment.

David Cockroft, general secretary of the ITF says:

Arms smuggling, the ability to conceal large sums of money, trafficking in goods and people and other illegal activities can also thrive in the unregulated havens which the flag of convenience system provides.—[11]

Concealed ownership

Shipowners often establish shell corporations to be the legal owners of their ships.[33] To distinguish between the actual shipowner and the shell corporations, the terms beneficial owner or ultimate owner are often used. Webster's defines a beneficial owner as "one who enjoys the benefit of a property of which another is the legal owner."[34] A ship's beneficial owner is legally and financially responsible for the ship and its activities.[35]

The 2004 Report of the UN Secretary General’s Consultative Group on Flag State Implementation reported that "It is very easy, and comparatively inexpensive, to establish a complex web of corporate entities to provide very effective cover to the identities of beneficial owners who do not want to be known."[36] According to a 2003 report by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development report entitled "Ownership and Control of Ships", these corporate structures are often multi-layered, spread across numerous jurisdictions, and make the beneficial owner "almost impenetrable" to law enforcement officials and taxation.[33] The report concludes that "regardless of the reasons why the cloak of anonymity is made available, if it is provided it will also assist those who may wish to remain hidden because they engage in illegal or criminal activities, including terrorists."[33]

The OECD report concludes that the use of bearer shares is "perhaps the single most important (and perhaps the most widely used) mechanism" to protect the anonymity of a ship's beneficial owner.[37] Physically possessing a bearer share accords ownership of the corporation.[37] There is no requirement for reporting the transfer of bearer shares, and not every jurisdiction requires that their serial numbers even be recorded.[37]

Two similar techniques to provide anonymity for a ship's beneficial owner are "nominee shareholders" and "nominee directors." In some jurisdictions that require shareholder identities to be reported, a loophole is created where the beneficial owner may appoint a nominee to be the shareholder, and that nominee cannot legally be compelled to reveal the identity of the beneficial owner.[38] All corporations are required to have at least one director, however many jurisdictions allow this to be a nominee director.[39] A nominee director's name would appear on all corporate paperwork in place of the beneficial owners, and like nominee shareholders, few jurisdictions can compel a nominee director to divulge the identity of beneficial owners.[39] To further complicate matters, some jurisdictions allow a corporation to fulfill the duties of a nominee director.[39]

Crime

Flag of convenience ships have long been linked to crime on the high seas. For example, in 1982, Honduras shut down its open registry operations because it had enabled "illegal traffic of all kinds and had given Honduras a bad name."[40]

Ships registered by the Cambodia Shipping Corporation (CSC) were found smuggling drugs and cigarettes in Europe, breaking the Iraq oil embargo, and engaging in human trafficking and prostitution in Europe and Asia.[11] In response to these activities, in 2000, Ahamd Yahya of the Cambodian Ministry of Public Works and Transport told industry publication Fairplay "We don't know or care who owns the ships or whether they're doing 'white' or 'black' business ... it is not our concern."[11] Less than two years later, French forces seized the Cambodian-flagged, Greek-owned MV Winner for cocaine smuggling.[11] Shortly after the seizure, Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen closed the registry to foreign ships,[11] and Cambodia canceled its contract with CSC shortly thereafter.[41]

The North Korean flag of convenience has also garnered significant scrutiny. In 2003, the North Korean freighter Pong-su reflagged to Tuvalu in the middle of a voyage shortly before being seized by Australian authorities for smuggling heroin into that country.[11] That year thirteen nations began monitoring vessels under the North Korean flag for "illicit cargos, like drugs, missiles or nuclear weapon fuel."[41] In 2006, ships owned by Egyptian and Syrian interests, flagged by North Korea, and based in the United States were discovered to be engaged in smuggling migrants in Europe.[11]

Terrorism

The OECD report states that the possibility of terrorists using ships is "obvious" and "potentially devastating" and goes on to list ways in which ships could be used.[42] One clear use would be to move personnel, equipment, and weapons around the world.[42] Another would be to transport bombs, such as a "container set to explode near a city."[42] Also, ships could be used as a weapon in their own right, for example an oil tanker or liquefied natural gas carrier rigged as a floating bomb.[42] Finally, the OECD discussed the possibility of criminal and terrorist organizations using ships engaging in legal or illegal trade as a source of revenue to fund criminal activities.[43]

In 2002 in the United States, Democratic senator John Breaux of Louisiana proposed a bill to prevent U.S. shipowners from using foreign flags as a counter-terrorism measure.[44]

Working conditions

In the accompanying material of the ILO's Maritime Labour Convention of 2006, the International Labour Organization estimated that at that time there were approximately 1,200,000 working seafarers across the world.[45] This document goes on to say that when working aboard ships flagged to states that do not "exercise effective jurisdiction and control" over their ships that "seafarers often have to work under unacceptable conditions, to the detriment of their well-being, health and safety and the safety of the ships on which they work."[46]

The International Transport Workers' Federation goes further, stating that flags of convenience "provide a means of avoiding labor regulation in the country of ownership, and become a vehicle for paying low wages and forcing long hours of work and unsafe working conditions. Since FOC ships have no real nationality, they are beyond the reach of any single national seafarers' trade union."[47] They also say that these ships have low safety standards and no construction requirements, that they "do not enforce safety standards, minimum social standards or trade union rights for seafarers",[48] that they frequently fail to pay their crews,[7] have poor safety records,[7] and engage in practices such as abandoning crewmen in distant ports.[7]

According to the Maritime Trades Department of the AFL-CIO,

These floating sweatshops are the building blocks of the notorious "Flag-of-Convenience" (FOC) system. It exists for one reason and one reason only: to allow companies to avoid paying taxes and escape the minimum health, safety and environmental standards of their home countries.—[49]

Environmental effects

While flag of convenience ships have been involved with some of the highest-profile oil spills in history (such as the Maltese-flagged MV Erika,[50] the Bahamian-flagged MV Prestige,[51] the Marshallese-flagged Deepwater Horizon,[52] and the Liberian-flagged MV Amoco Cadiz[53] and MV Sea Empress[54]) the most common environmental criticism they face regards illegal fishing. These critics of the flag of convenience system argue that many of the FOC flag states lack the resources or the will to properly monitor and control those vessels. The Environmental Justice Foundation (EJF) contends that illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing (IUU) vessels use flags of convenience to avoid fisheries regulations and controls. Flags of convenience help reduce the operating costs associated with illegal fishing methods, and help illegal operators avoid prosecution and hide beneficial ownership.[55] As a result, flags of convenience perpetuate IUU fishing which has extensive environmental, social and economic impacts, particularly in developing countries.[56] The EJF is campaigning to end the granting of flags of convenience to fishing vessels as an effective measure to combat IUU fishing.

According to Franz Fischler, European Union Fisheries Commissioner,

The practice of flags of convenience, where owners register vessels in countries other than their own in order to avoid binding regulations or controls, is a serious menace to today’s maritime world.—[57]

Ratification of maritime conventions

| Flag | SOLAS | MARPOL | LL66 | ILO147 | CLC/FUND92 |

| Antigua/Barbuda | X | ||||

| Bahamas | X | ||||

| Bolivia | X | X | X | X | X |

| Cambodia | X | X | |||

| North Korea | X | X | X | ||

| Georgia | X | X | X | ||

| Honduras | X | X | X | X | X |

| Jamaica | X | ||||

| Lebanon | X | X | X | ||

| Malta | X | ||||

| Mongolia | X | X | |||

| St. Vincent/Grenadines | X | ||||

| Sri Lanka | X | X | X | X |

International regulations for the maritime industry are promulgated by agencies of the United Nations, particularly the International Maritime Organization and International Labour Organization. Flag states adopt these regulations for their ships by ratifying individual treaties. One common criticism against flag of convenience countries is that they allow shipowners to avoid these regulations by not ratifying important treaties or by failing to enforce them.

Maritime International Secretariat Services (MARISEC) issues a yearly report entitled the Flag State Performance Table in association with industry groups the Baltic and International Maritime Council, the International Association of Dry Cargo Shipowners, the International Chamber of Shipping, the International Shipping Federation, and the International Association of Independent Tanker Owners.[59] The 2009 report identified the six "core" conventions representing a minimum level of maritime regulation, from the viewpoint of shipowners, as SOLAS, MARPOL, LL 66, STCW, ILO 147, and CLC/FUND92.[59] Five of these six core conventions are not ratified by several flag of convenience countries.

The SOLAS and LL 66 conventions focus on shipboard safety issues. SOLAS is an acronym for Safety of Life at Sea, or formally "International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea, 1974 as amended, including the 1988 Protocol, the International Safety Management Code (ISM) and the International Ship and Port Facility Security Code (ISPS)". Originally ratified in response to the sinking of the RMS Titanic, SOLAS sets regulations on lifeboats, emergency equipment and safety procedures, including continuous radio watches. It has been updated to include regulations on ship construction, fire protection systems, life-saving appliances, radio communications, safety of navigation, management for the safe operation of ships, and other safety and security concerns.[60] As of 2009[update], the Bolivian, Honduran, Lebanese, and Sri Lankan flags of convenience have not ratified the SOLAS treaty.[58] LL 66 is an industry designation for the "International Convention on Load Lines, 1966, including the 1988 Protocol".[58] This convention sets standards for minimum buoyancy, hull stress, and ship's fittings, as well as establishing navigational zones where extra precautions must be taken.[61] As of 2009[update], the Bahamian, Bolivian, Georgian, Honduran, and Sri Lankan flags of convenience have not ratified the LL 66 treaty.[58]

ILO147 is shorthand for the "International Labour Organization Merchant Shipping (Minimum Standards) Convention 1976, including the 1996 Protocol". This convention sets safety and competency standards, regulates work hours, manning, conditions of employment as well as shipboard living arrangements.[62] As of 2009[update], the Antigua/Barbudan, Bolivian, Cambodian, North Korean, Georgian, Honduran, Jamaican, Mongolian, Vincentian, and Sri Lankan flags of convenience have not ratified the ILO147 treaty.[58]

MARPOL, CLC, and FUND are treaties related to pollution. MARPOL refers to the "International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships,1973 as modified by the Protocol of 1978, including Annexes I – VI". This treaty regulates pollution by ships, including oil and air pollution, shipboard sewage and garbage.[63] As of 2009[update], the Bahamian, Bolivian, Cambodian, North Korean, Georgian, Honduran, Lebanese, Maltese, and Sri Lankan flags of convenience have not ratified the MARPOL treaty.[58] CLC and FUND92 refer to the "International Convention on Civil Liability for Oil Pollution Damage, 1992" and the "International Convention on the Establishment of an International Fund for Compensation for Oil Pollution Damage, 1992". These two related conventions provide mechanisms to ensure remuneration for victims of oil spills.[64][65] As of 2009[update], the Bolivian, North Korean, Honduran, Lebanese, and, Mongolian flags of convenience have not ratified the CLC and FUND treaties.[58]

Port state targeting

| Flag | Paris Blacklist |

Tokyo Blacklist |

US Target List |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antigua/Barbuda | X | ||

| Bahamas | X | ||

| Belize | X | X | |

| Bolivia | X | ||

| Cambodia | X | X | X |

| Cayman Islands | X | ||

| North Korea | X | X | |

| Georgia | X | X | |

| Honduras | X | X | |

| Lebanon | X | ||

| Malta | X | ||

| Mongolia | X | X | |

| Panama | X | X | |

| St. Vincent/Grenadines | X |

In 1978, a number of European countries agreed in The Hague to audit labour conditions on board vessels vis-a-vis the rules of the International Labour Organization. To this end, in 1982 the "Paris Memorandum of Understanding on Port State Control" (Paris MOU) was established, setting port state control standards for what is now twenty-six European countries and Canada.

Several other regional Memoranda Of Understanding have been established based on the Paris model, including the "Memorandum of Understanding on Port State Control in the Asia-Pacific Region", typically referred to as the "Tokyo MOU", and organizations for the Black Sea, the Caribbean, the Indian Ocean, the Mediterranean, and Latin America.[66] The Tokyo and Paris organizations generate, based on deficiencies and detentions, black-, white-, and grey-lists of flag states. The US Coast Guard, which handles port state control inspections in the US, maintains a similar target list for underperforming flag states. As of 2009[update], fourteen of the thirty-one flags of convenience listed by the ITF are targeted for special enforcement by the countries of the Paris and Tokyo MOUs or U.S. Coast Guard: Antigua and Barbuda, the Bahamas, Belize, Bolivia, Cambodia, the Cayman Islands, North Korea, Georgia, Honduras, Lebanon, Malta, Mongolia, Panama, and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines.[58]

Wages

The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, in its 2009 Report on Maritime Trade, states that shipowners often register their ships under a foreign flag in order to employ "seafarers from developing countries with lower wages."[67] The Philippines and the People's Republic of China supply a large percentage of maritime labor in general,[68] and major flags of convenience in particular. In 2009, the flag-states employing the highest number of expatriate-Filipino seafarers were Panama, the Bahamas, Liberia and the Marshall Islands.[69] That year, more than 150,000 Filipino sailors were employed by these four flags of convenience.[69] In a 2006 study by the United States Maritime Administration (MARAD), sailors from the People's Republic of China comprised over 40% of the crews on surveyed ships flying the Panamanian flag, and around 10% of those flying the Liberian flag.[70] The MARAD report referred to both China and the Philippines as "low cost" crewing sources.[71]

The seafaring industry is often divided into two employment groups: licensed mariners including deck officers and marine engineers, and mariners that are not required to have licenses, such as able seamen and cooks. The latter group is collectively known as unlicensed mariners or ratings. Differences in wages can be seen in both groups, between "high cost" crewing sources such as the United States, and "low cost" sources such as China and The Philippines.

For unlicensed mariners, 2009 statistics from the American Bureau of Labor Statistics give median earnings for able and ordinary seamen as US$35,810, varying from $21,640 (at the 10th percentile) to $55,360 (at the 90th percentile).[72] This can be compared with 2006 statistics from the International Labour Organization, giving average yearly earnings for Filipino and Chinese able seamen around $2,000 to $3,000 per year (PHP9,900 per month and CNY3,071 per year).[73][74] Among licensed mariners, American chief engineers earned a median $63,630, varying from $35,030 to $109,310 while their Filipino counterparts averaged $5,500 per year (PHP21,342 per month).[74][75]

Footnotes

- ^ Ministry of Transport (2010). "MOL Pride". Equasis. Government of France. http://www.equasis.org/EquasisWeb/restricted/ShipList?fs=ShipSearch&P_PAGE=1&P_IMO=8705541. Retrieved 2010-07-23. (Free registration required.)

- ^ a b ICFTU et al., 2002, p. 7.

- ^ Bernaert, 2006, p. 104.

- ^ That the flag state gives the right to fly its flag, see United Nations, 1982, Article 91. That this flag is called a civil ensign, see De Kleer, 2007, p. 37.

- ^ Hamzah, 2004, p.4.

- ^ "U.S. Coast Guard Alternative Compliance Program". United States Coast Guard. http://www.uscg.mil/hq/cg5/acp/. Retrieved 2010-07-01.

- ^ a b c d e f g Working, 1999.

- ^ Dempsey and Helling, 1980.

- ^ From the American Heritage dictionary definition available on-line at "Flag of convenience". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition. Huntingdon Valley, PA: Farlex Inc.. 2003. http://www.thefreedictionary.com/flag+of+convenience. Retrieved 2010-08-25. or "Flag of convenience". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition. Burlingame, CA: LoveToKnow Corp. 2003. http://www.yourdictionary.com/flag-of-convenience. Retrieved 2010-08-25.

- ^ Richardson, 2003.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Neff, 2007.

- ^ a b c Secretariat of the Paris Memorandum of Understanding on Port State Control (2010) "A short history of the Paris MOU" Paris: Paris Memorandum of Understanding on Port State Control http://www.parismou.org/ParisMOU/Organisation/About+Us/History/default.aspx. Retrieved 2010-07-01

- ^ Secretariat of the Paris Memorandum of Understanding, 2009.

- ^ Secretariat of the Paris Memorandum of Understanding, 2009, p 27.

- ^ Secretariat of the Tokyo Memorandum of Understanding, 2009, p 22.

- ^ D'Andrea 2006, p.2.

- ^ a b c d D'Andrea 2006, p.6.

- ^ Wiswall 1996, p. 113.

- ^ Kemp, 1976.

- ^ Bornstein, David (2011-01-13). "The Transatlantic Slave Trade and the Civil War". Opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com. http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/01/13/the-transatlantic-slave-trade-and-the-civil-war/. Retrieved 2011-03-28.

- ^ Merriam-Webster Incorporated, 2003, p.474.

- ^ a b c d DeSombre 2006, p. 75.

- ^ a b c d Marquis, Greg (2007). "Brutality on Trial (review)". Law and Politics Book Review. http://www.bsos.umd.edu/gvpt/lpbr/subpages/reviews/gibson0107.htm. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- ^ a b DeSombre 2006, p. 76.

- ^ a b c d DeSombre 2006, p. 74.

- ^ a b c d e f Pike, 2008.

- ^ "Charles Taylor Trial Background". Charlestaylortrial.org. http://www.charlestaylortrial.org/trial-background/. Retrieved 2010-07-01.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "Chapter 2, Structure and ownership of the world fleet" (PDF). Review of Maritime Transport 2009 (UNCTAD): 36. December 2009. http://www.unctad.org/en/docs/rmt2009_en.pdf. Retrieved 2010-06-21.

- ^ a b c d International Transport Workers' Federation. "What are Flags of Convenience?". http://www.itfglobal.org/flags-convenience/sub-page.cfm. Retrieved 2007-05-04.

- ^ a b "FOC Countries". International Transport Workers' Federation. 2005-06-06. http://www.itfglobal.org/flags-convenience/flags-convenien-183.cfm. Retrieved 2010-07-02.

- ^ ISL: Shipping Statistics Yearbook 2008, page 27. Institute of Shipping Economics and Logistics, 2009.

- ^ American Bureau of Shipping (ABS) (2010). "Deepwater Horizon (Vessel Details)". ABS Record. American Bureau of Shipping. http://www.eagle.org/safenet/record/record_vesseldetailsprinparticular?Classno=0139290&Accesstype=PUBLIC&ReferrerApplication=PUBLIC2. Retrieved 2010-06-12.

- ^ a b c Gianni 2008, p. 20.

- ^ "Beneficial Owner". Merriam-Webster's Dictionary of Law. Merriam-Webster's Inc.. 1996. http://dictionary.lp.findlaw.com/scripts/results.pl?co=dictionary.lp.findlaw.com&topic=b9/b937a76fa541981941f5f389cd3fba2e. Retrieved 2010-06-24.

- ^ OECD 2003, p. 4.

- ^ Gianni 2008, p. 19.

- ^ a b c OECD 2003, p. 8.

- ^ OECD 2003, pp. 8–9.

- ^ a b c OECD 2009, p. 9.

- ^ Reuters, 1982.

- ^ a b Brooke, 2004.

- ^ a b c d OECD 2003, p.5.

- ^ OECD 2003, pp. 6.

- ^ The Economist, 2002.

- ^ International Labour Organization, "Maritime Labour Convention 2006, Frequently Asked Questions", p. 5.

- ^ International Labour Organization, "Maritime Labour Convention 2006, Frequently Asked Questions", pp. 4–5.

- ^ International Transport Workers' Federation. "Flags of Convenience campaign". http://www.itfglobal.org/flags-convenience/index.cfm. Retrieved 2007-05-04.

- ^ What do FOC's mean to seafarers? International Transport Workers' Federation

- ^ Maritime Trades Department (2007-09-16). "Flags-of-Convenience Campaign". AFL-CIO. http://www.maritimetrades.org/article.php?sid=33. Retrieved 2010-07-01.

- ^ Centre of Documentation, Research and Experimentation on Accidental Water Pollution (CEDRE) (November 2009). "Erika". Brest: Centre of Documentation, Research and Experimentation on Accidental Water Pollution. http://www.cedre.fr/en/spill/erika/erika.php. Retrieved 2010-06-30.

- ^ Centre of Documentation, Research and Experimentation on Accidental Water Pollution (CEDRE) (April 2006). "Prestige". Brest: Centre of Documentation, Research and Experimentation on Accidental Water Pollution. http://www.cedre.fr/en/spill/prestige/prestige.php. Retrieved 2010-06-30.

- ^ Centre of Documentation, Research and Experimentation on Accidental Water Pollution (CEDRE) (June 2010). "Deepwater Horizon". Brest: Centre of Documentation, Research and Experimentation on Accidental Water Pollution. http://www.cedre.fr/en/spill/deepwater_horizon/deepwater_horizon.php. Retrieved 2010-06-30.

- ^ Centre of Documentation, Research and Experimentation on Accidental Water Pollution (CEDRE) (April 2006a). "Amoco Cadiz". Brest: Centre of Documentation, Research and Experimentation on Accidental Water Pollution. http://www.cedre.fr/en/spill/amoco/amoco.php. Retrieved 2010-06-30.

- ^ Centre of Documentation, Research and Experimentation on Accidental Water Pollution (CEDRE) (April 2006b). "Sea Empress". Brest: Centre of Documentation, Research and Experimentation on Accidental Water Pollution. http://www.cedre.fr/en/spill/sea_emp/sea_empress.php. Retrieved 2010-06-30.

- ^ Gianni & Simpson, 2005.

- ^ Environmental Justice Foundation, 2009.

- ^ ICFTU et al., 2002. Page 5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i MARISEC, 2009.

- ^ a b MARISEC 2009, p.1.

- ^ "International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea". International Maritime Organization. http://www.imo.org/Conventions/contents.asp?topic_id=257&doc_id=647. Retrieved 2010-07-01.

- ^ "International Convention on Load Lines, 1966". International Maritime Organization. Archived from the original on 2007-02-19. http://web.archive.org/web/20070219233313/http://www.imo.org/conventions/mainframe.asp?topic_id=254. Retrieved 2010-07-01.

- ^ "Merchant Shipping (Minimum Standards) Convention, 1976". International Labour Organization. http://www.ilo.org/ilolex/cgi-lex/convde.pl?C147. Retrieved 2010-07-01.

- ^ "International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships, 1973, as modified by the Protocol of 1978 relating thereto (MARPOL 73/78)". International Maritime Organization. Archived from the original on 2008-06-12. http://web.archive.org/web/20080612185045/http://www.imo.org/Conventions/mainframe.asp?topic_id=258&doc_id=678. Retrieved 2010-07-01.

- ^ "International Convention on Civil Liability for Oil Pollution Damage (CLC), 1969". International Maritime Organization. http://www.imo.org/conventions/contents.asp?doc_id=660&topic_id=256#4. Retrieved 2010-07-01.

- ^ "International Convention on the Establishment of an International Fund for Compensation for Oil Pollution Damage (FUND), 1971". International Maritime Organization. http://www.imo.org/Conventions/contents.asp?doc_id=661&topic_id=256. Retrieved 2010-07-02.

- ^ Tokyo MOU Secretariat, 2008.

- ^ "Chapter 2, Structure and ownership of the world fleet" (PDF). Review of Maritime Transport 2009 (UNCTAD): 57. December 2009. http://www.unctad.org/en/docs/rmt2009_en.pdf. Retrieved 2010-08-15.

- ^ Baltic and International Maritime Council; International Shipping Federation (2005) "Numbers and nationality of world's seafarers" Shipping and World Trade London: Maritime International Secretariat Services http://www.marisec.org/shippingfacts/worldtrade/world-seafarers.php

- ^ a b Philippine Overseas Employment Administration (2009) "Overseas Employment Statistics" Mandaluyong City, Philippines: Republic of the Philippines p. 28 http://www.poea.gov.ph/stats/2009_OFW%20Statistics.pdf

- ^ Maritime Administration, 2006, p. 14.

- ^ Maritime Administration, 2006, p. 13-14.

- ^ "Sailors and Marine Oilers". Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2010-05-14. http://www.bls.gov/oes/2009/may/oes535011.htm. Retrieved 2010-07-02.

- ^ From Department of Statistics (2006) "LABORSTA" Geneva: International Labour Office http://laborsta.ilo.org/. Retrieved 2010-07-01. Expand "Wages" tab. Select "Wages and hours of work in 159 occupations." Select "China" and click "Go." Click "view." Data under "Able seaman".

- ^ a b From Department of Statistics (2006) "LABORSTA" Geneva: International Labour Office http://laborsta.ilo.org/. Retrieved 2010-07-01. Expand "Wages" tab. Select "Wages and hours of work in 159 occupations." Select "Philippines" and click "Go." Click "view." Data under "Ship's chief engineer" and "Able seaman".

- ^ "Ship Engineers". Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2010-05-14. http://www.bls.gov/oes/2009/may/oes535031.htm. Retrieved 2010-07-02.

References

- Bernaert, Andy (2006) [1988]. Bernaerts' Guide to the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. Victoria, B.C., Canada: Trafford Publishing. ISBN 1-4120-7665-x. http://books.google.com/?id=F0z8Z3zZEh8C&pg=PA104&dq=flag-state+%22flag+of+convenience%22&q=flag-state%20%22flag%20of%20convenience%22. Retrieved 2010-08-14.

- D'Andrea, Ariella (November 2006) The "Genuine Link" Concept in Responsible Fisheries [Legal Aspects and Recent Developments] FAO Legal Papers Online 61 Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization http://www.fao.org/legal/prs-ol/lpo61.pdf. Retrieved 2010-06-30

- De Kleer, Vicki (2007). Flags of the World: A Visual Guide To The. London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 1-86176-305-0. http://books.google.com/?id=KIzejlnvl6wC&pg=PA37&dq=%22civil+ensign%22&q=%22civil%20ensign%22. Retrieved 2010-08-14.

- The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 0395825172. http://www.yourdictionary.com/flag-of-convenience. Retrieved 2010-08-14.

- Dempsey, P.S.; Helling, L.L. (September 1, 1980). "Oil pollution by ocean vessels – an environmental tragedy: the legal regime of flags of convenience, multilateral conventions, and coastal states". Denver Journal of International Law Policy 10 (1): 37–87. http://www.osti.gov/energycitations/product.biblio.jsp?osti_id=6339199.

- DeSombre, Elizabeth (2006). Flagging Standards : Globalization and Environmental, Safety, and Labor Regulations at Sea. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. ISBN 9780262541909. http://books.google.com/?id=MRe0ig0-nO8C&lpg=PA76&dq=%22Belen%20Quezada%22%20%2BPanama&pg=PA76#v=onepage&q=%22Belen%20Quezada%22%20+Panama. Retrieved 2010-06-13.

- Gianni, Matthew (2008). "Real and Present Danger: Flag State Failure and Maritime Security and Safety". Oslo & London: International Transport Worker's Federation. http://assets.panda.org/downloads/flag_state_performance.pdf. Retrieved 2010-06-24.

- International Confederation of Free Trade Unions; Trade Union Advisory Committee to the OECD; International Transport Workers’ Federation; Greenpeace International (2002). More Troubled Waters: Fishing, Pollution, and FOCs. Johannesburg: 2002 World Summit on Sustainable Development. http://www.itfglobal.org/infocentre/pubs.cfm/detail/24668. Retrieved 2011-08-14.

- International Labour Organization. FAQ regarding the Consolidated Maritime Convention of 2006. Geneva: International Labour Organization. ISBN 9221186431. http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_norm/---normes/documents/publication/wcms_088042.pdf. Retrieved 2010-06-12.

- Maritime Administration (November 2006) "A Review of Crewing Practices in U.S.-Foreign Ocean Cargo Shipping" Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Transportation p. 9 http://www.marad.dot.gov/documents/Crewing_Report_Internet_Version_in_Word-update-Jan_final.pdf. Retrieved 2010-08-15

- "Ownership and Control of Ships" Directorate for Science, Technology and Industry Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 2003 http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/53/9/17846120.pdf. Retrieved 2010-06-25

- Merriam-Webster Incorporated (2003). Merriam-Webster's collegiate dictionary. Springfield, Massachusetts: Merriam-Webster, Inc. ISBN 0-87779-808-7. http://books.google.com/?id=TAnheeIPcAEC&pg=RA1-PA474&lpg=RA1-PA474&dq=%22registry+of+a+merchant+ship+under+a+foreign+flag+in+order+to+profit+from+less+restrictive+regulations%22&q=%22registry%20of%20a%20merchant%20ship%20under%20a%20foreign%20flag%20in%20order%20to%20profit%20from%20less%20restrictive%20regulations%22. Retrieved 2010-08-14.

- Kemp, Peter (1976). The Oxford Companion to Ships and the Sea. London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192820846. http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1O225-flagsofconvenience.html. Retrieved 2010-06-13.

- International Transport Workers' Federation. "What are Flags of Convenience?". http://www.itfglobal.org/flags-convenience/sub-page.cfm. Retrieved 2007-05-04.

- International Transport Workers' Federation. "FOC Countries". http://www.itfglobal.org/flags-convenience/flags-convenien-183.cfm. Retrieved 2007-05-04.

- Hamzah, B.A. (July 7, 2004). "Ports and Sustainable Development: Initial Thoughts" (PDF). United Nations Institute for Training and Research. p. 4. http://www2.unitar.org/hiroshima/programmes/shs04/Presentations%20SHS/7%20July/Hamzah_doc.pdf. Retrieved 2007-05-07.

- Foreign Flag Crewing Practices. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Transportation. 2006. http://www.marad.dot.gov/documents/Crewing_Report_Internet_Version_in_Word-update-Jan_final.pdf. Retrieved 2010-06-12.

- MARISEC (2009). Shipping Industry Flag State Performance Table. London: Maritime International Secretariat Services. pp. 1–2. http://www.marisec.org/shippingfacts/uploads/File/FlagStatePerformanceTable09.pdf?SID=lghwfzybi. Retrieved 2010-06-12.

- MARISEC (2009b). Shipping Industry Guidelines on Flag State Performance, Second Edition. London: Maritime International Secretariat Services. http://www.marisec.org/flag-performance.pdf. Retrieved 2010-06-12.

- Pike, John (2008). "History of Liberian Ship Registry". GlobalSecurity.org. http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/liberia/registry.htm. Retrieved 2010-06-20.

- Richardson, Michael (2003) "Crimes Under Flags of Convenience" YaleGlobal Online New Haven, Connecticut: Yale Center for the Study of Globalization http://yaleglobal.yale.edu/content/crimes-under-flags-convenience. Retrieved 2010-08-25

- United Nations (1982). "Part VII: The High Seas". United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). United Nations. http://www.un.org/Depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/part7.htm. Retrieved 2010-06-14.

- Wiswall, Frank, Jr. (1996) "Flags of Convenience" in Lovett, William United States Shipping Policies and the World Market Westport, CT: Quorum ISBN 0899309453 http://books.google.com/?id=2gXpKzu1wz4C&lpg=PP1&dq=United%20States%20shipping%20policies%20and%20the%20world%20market&pg=PP4#v=onepage&q

News stories

- Brooke, James (07-02-2004). "Landlocked Mongolia's Seafaring Tradition". New York Times. New York Times. http://www.globalpolicy.org/nations/flags/2004/0702landlocked.htm. Retrieved 2010-06-12.

- The Economist (May 16, 2002). "Brassed Off: How the war on terrorism could change the shape of shipping". The Economist. http://www.globalpolicy.org/nations/flags/2002/0520osama.htm.

- Fleshman, Michael (2001). "Conflict diamonds evade UN sanctions: Improvements in Sierra Leone, but continuing violations in Angola and Liberia". Africa Recovery (United Nations) 15 (4): 15. http://www.un.org/ecosocdev/geninfo/afrec/vol15no4/154diam.htm.

- Neff, Robert (2007-04-20). "Flags That Hide the Dirty Truth". Asia Times. Asia Times Online. http://www.atimes.com/atimes/Korea/ID20Dg03.html. Retrieved 2010-06-12.

- Reuters (11-09-1982). "Honduras Cuts Ship Registry". New York Times (New York Times). http://www.nytimes.com/1982/11/09/world/honduras-cuts-ship-registry.html. Retrieved 2010-06-12.

- Working, Russell (May 22, 1999). "Flags of Inconvenience; Union Campaigns Against Some Foreign Ship Registry". New York Times. http://www.globalpolicy.org/nations/union99.htm. Retrieved 2007-05-04.

Fishing references

- Environmental Justice Foundation. Lowering The Flag: Ending the Use of Flags of Convenience by Pirate Fishing Vessels. London. ISBN 1904523196. http://www.illegal-fishing.info/uploads/Loweringtheflagfinal.pdf. Retrieved 06-12-2010.

- Gianni, Matthew; Simpson, Walt (10-01-2005). The Changing Nature of High Seas Fishing [How flags of convenience provide cover for illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing]. Australian Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry, International Transport Workers’ Federation, and WWF International. http://assets.panda.org/downloads/iiumr.pdf. Retrieved 2010-06-12.

Port state control organizations

- Secretariat of the Black Sea Memorandum of Understanding on Port State Control (2008) "Annual Report for 2008" Istanbul: Black Sea Memorandum of Understanding on Port State Control http://www.bsmou.org/files.php?file=PDF/ANNUALREPORT2008.pdf. Retrieved 2010-06-29

- Secretariat of the Memorandum of Understanding on Port State Control in the Caribbean Region (2007) "Annual Report of the Caribbean Memorandum of Understanding on Port State Control" Kingston, Jamaica: Memorandum of Understanding on Port State Control in the Caribbean Region http://www.caribbeanmou.org/docs/annual_report_07.pdf. Retrieved 2010-06-29

- Indian Ocean Memorandum of Understanding Secretariat (2009) "Annual Report 2009" Goa, India: Indian Ocean Memorandum of Understanding http://www.iomou.org/php/xmldata/annrep09.pdf. Retrieved 2010-06-29

- Secretariat of the Mediterranean Memorandum of Understanding on Port State Control (2007) "Memorandum of Understanding on Port State Control in the Mediterranean Region" Alexandria http://81.192.52.75/Med_MoU_Text.html. Retrieved 2010-06-29

- Secretariat of the Paris Memorandum of Understanding (2009) "Annual Report 2008 [Port State Control: Making Headway]" Paris: Secretariat of the Paris Memorandum on Port State Control http://www.parismou.org/upload/anrep/Annual%20Report%202008.pdf. Retrieved 2010-06-29

- Tokyo MOU Secretariat (2010) "Annual Report on Port State Control in the Asia-Pacific Region" Tokyo: Port State Control Committee of the Memorandum of Understanding on Port State Control in the Asia-Pacific Region (Tokyo MOU) http://www.tokyo-mou.org/ANN09.pdf. Retrieved 2010-06-29

- Secretary of the Latin American Agreement on Port State Control (2008) "Latin American Agreement on Port State Control of Vessels (Acuerdo de Viña del Mar)" Buenos Aires http://200.45.69.62/informes/EN/INFORME_ANUAL_2008.zip. Retrieved 2010-06-29

- United States Coast Guard (2010-060-29) "Annual Targeted Flag List" Washington, D.C.: United States Department of Homeland Security http://homeport.uscg.mil/mycg/portal/ep/contentView.do?channelId=-18371&contentId=21904&programId=21428&programPage=%2Fep%2Fprogram%2Feditorial.jsp&pageTypeId=13489&contentType=EDITORIAL. Retrieved 2010-06-29

Further reading

- Alderton, A.F.; Winchester, N. (2002). "Globalisation and De-Regulation in the Maritime Industry". Marine Policy 26 (1): 35–43. doi:10.1016/S0308-597X(01)00034-3.

- Alderton, A.F.; Winchester, N. (September 2002). "Regulation, Representation and the Flag Market". Journal of Maritime Research. http://www.jmr.nmm.ac.uk/server.php?navId=009.

- Alderton, A.F.; Winchester, N. (2002). "Flag States and Safety, 1997–1999". Maritime Policy and Management 29 (2): 151–162. doi:10.1080/03088830110090586.

- Carlisle, Rodney. (1981). Sovereignty for Sale: The Origin and Evolution of the Panamanian and Liberian Flags of Convenience. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-668-6

- Carlisle, Rodney. (2009). Second Registers: Maritime Nations Respond to Flags of Convenience, 1984–1998. The Northern Mariner/Le marin du nord, 19:3, 319–340.

- The Economist (May 27, 2000). "Bolivia Waves the Flag". The Economist. http://www.globalpolicy.org/nations/flags.htm.

- Toweh, Alphonso. (March 3, 2008). "Shipping's flag of convenience pays off for Liberia". Business Day (Rosebank, South Africa: BDFM Publishers (Pty) Ltd.). http://www.hellenicshippingnews.com/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=1494&Itemid=32. Retrieved 2008-03-13.

- United Nations (February 7, 1986). "United Nations Convention on Conditions for Registration of Ships". http://r0.unctad.org/ttl/docs-legal/unc-cml/United%20Nations%20%20Convention%20on%20Conditions%20for%20Registration%20of%20Ships,%201986.pdf. Retrieved 2007-05-05.

- United States House Committee on Armed Services (June 13, 2002). "HASC No. 107-42, Vessel Operations Under Flags of Convenience". United States House of Representatives. http://commdocs.house.gov/committees/security/has164220.000/has164220_0.HTM. Retrieved 2007-05-04.

- United States Senate (September 6, 2000). "Senate Report 106-396 – United States Cruise Vessel Act". http://thomas.loc.gov/cgi-bin/cpquery/?&sid=cp106BRzkB&refer=&r_n=sr396.106&db_id=106&item=&sel=TOC_3674&. Retrieved 2007-05-04.

External links

- Database on reported incidents of abandonment of seafarers

- Flag of Convenience Cyprus: Prestige Oil Spill

- List of flag State comments on detentions for the years 2000, 2001 and 2002

- Barlaan, Carl Allan; Cardiente, Christian (2011-09-10) "A sea of trouble" Manila Standard Today Manila: Kamahalan Publishing Corporation= http://www.manilastandardtoday.com/insideOpinion.htm?f=2011/september/10/feature1.isx&d=2011/september/10. Retrieved 2011-09-10