Fixed point (mathematics)

- Not to be confused with a stationary point where f'(x) = 0.

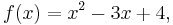

In mathematics, a fixed point (sometimes shortened to fixpoint, also known as an invariant point) of a function is a point[1] that is mapped to itself by the function. A set of fixed points is sometimes called a fixed set. That is to say, c is a fixed point of the function f(x) if and only if f(c) = c. For example, if f is defined on the real numbers by

then 2 is a fixed point of f, because f(2) = 2.

Not all functions have fixed points: for example, if f is a function defined on the real numbers as f(x) = x + 1, then it has no fixed points, since x is never equal to x + 1 for any real number. In graphical terms, a fixed point means the point (x, f(x)) is on the line y = x, or in other words the graph of f has a point in common with that line. The example f(x) = x + 1 is a case where the graph and the line are a pair of parallel lines.

Points which come back to the same value after a finite number of iterations of the function are known as periodic points; a fixed point is a periodic point with period equal to one. In projective geometry, a fixed point of a collineation is called a double point.[2]

Contents |

Attractive fixed points

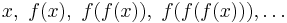

An attractive fixed point of a function f is a fixed point x0 of f such that for any value of x in the domain that is close enough to x0, the iterated function sequence

converges to x0. An expression of prerequisites and proof of the existence of such solution is given by Banach fixed point theorem.

The natural cosine function ("natural" means in radians, not degrees or other units) has exactly one fixed point, which is attractive. In this case, "close enough" is not a stringent criterion at all—to demonstrate this, start with any real number and repeatedly press the cos key on a calculator (checking first that the calculator is in "radians" mode). It eventually converges to about 0.739085133, which is a fixed point. That is where the graph of the cosine function intersects the line  .

.

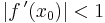

Not all fixed points are attractive: for example, x = 0 is a fixed point of the function f(x) = 2x, but iteration of this function for any value other than zero rapidly diverges. However, if the function f is continuously differentiable in an open neighbourhood of a fixed point x0, and  , attraction is guaranteed.

, attraction is guaranteed.

Attractive fixed points are a special case of a wider mathematical concept of attractors.

An attractive fixed point is said to be a stable fixed point if it is also Lyapunov stable.

A fixed point is said to be a neutrally stable fixed point if it is Lyapunov stable but not attracting. The center of a linear homogeneous differential equation of the second order is an example of a neutrally stable fixed point.

Theorems guaranteeing fixed points

There are numerous theorems in different parts of mathematics that guarantee that functions, if they satisfy certain conditions, have at least one fixed point. These are amongst the most basic qualitative results available: such fixed-point theorems that apply in generality provide valuable insights.

Applications

In many fields, equilibria or stability are fundamental concepts that can be described in terms of fixed points. For example, in economics, a Nash equilibrium of a game is a fixed point of the game's best response correspondence. However, in physics, more precisely in the theory of Phase Transitions, linearisation near an unstable fixed point has led to Wilson's Nobel prize-winning work inventing the renormalization group, and to the mathematical explanation of the term "critical phenomenon".

In compilers, fixed point computations are used for whole program analysis, which are often required to do code optimization.

The vector of PageRank values of all web pages is the fixed point of a linear transformation derived from the World Wide Web's link structure.

Logician Saul Kripke makes use of fixed points in his influential theory of truth. He shows how one can generate a partially defined truth predicate (one which remains undefined for problematic sentences like "This sentence is not true"), by recursively defining "truth" starting from the segment of a language which contains no occurrences of the word, and continuing until the process ceases to yield any newly well-defined sentences. (This will take a denumerable infinity of steps.) That is, for a language L, let L-prime be the language generated by adding to L, for each sentence S in L, the sentence "S is true." A fixed point is reached when L-prime is L; at this point sentences like "This sentence is not true" remain undefined, so, according to Kripke, the theory is suitable for a natural language which contains its own truth predicate.

The concept of fixed point can be used to define the convergence of a function.

Topological fixed point property

A topological space  is said to have the fixed point property (briefly FPP) if for any continuous function

is said to have the fixed point property (briefly FPP) if for any continuous function

there exists  such that

such that  .

.

The FPP is a topological invariant, i.e. is preserved by any homeomorphism. The FPP is also preserved by any retraction.

According to the Brouwer fixed point theorem, every compact and convex subset of a euclidean space has the FPP. Compactness alone does not imply the FPP and convexity is not even a topological property so it makes sense to ask how to topologically characterize the FPP. In 1932 Borsuk asked whether compactness together with contractibility could be a necessary and sufficient condition for the FPP to hold. The problem was open for 20 years until the conjecture was disproved by Kinoshita who found an example of a compact contractible space without the FPP.[3]

See also

Notes

- ^ The word point in this context means an element of the function's domain

- ^ H. S. M. Coxeter (1942) Non-Euclidean Geometry, page 36, University of Toronto Press

- ^ Kinoshita, S. On Some Contractible Continua without Fixed Point Property. Fund. Math. 40 (1953), 96–98