Følner sequence

In mathematics, a Følner sequence for a group is a sequence of sets satisfying a particular condition. If a group has a Følner sequence with respect to its action on itself, the group is amenable. A more general notion of Følner nets can be defined analogously, and is suited for the study of uncountable groups. Følner sequences are named for Erling Følner.

Contents |

Definition

Given a group  that acts on a set

that acts on a set  , a Følner sequence for the action is a sequence of finite subsets

, a Følner sequence for the action is a sequence of finite subsets  of

of  which exhaust

which exhaust  and which "don't move too much" when acted on by any group element. Precisely,

and which "don't move too much" when acted on by any group element. Precisely,

- For every

, there exists some

, there exists some  such that

such that  for all

for all  , and

, and  for all group elements

for all group elements  in

in  .

.

Explanation of the notation used above:

is the result of the set

is the result of the set  being acted on the left by

being acted on the left by  . It consists of elements of the form

. It consists of elements of the form  for all

for all  in

in  .

. is the symmetric difference operator.

is the symmetric difference operator. is the cardinality of a set

is the cardinality of a set  .

.

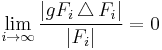

Thus, what this definition says is that for any group element  , the proportion of elements of

, the proportion of elements of  that are moved away by

that are moved away by  goes to 0 as

goes to 0 as  gets large.

gets large.

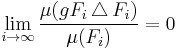

In the setting of a locally compact group acting on a measure space  there is a more general definition. Instead of being finite, the sets are required to have finite, non-zero measure, and so the Følner requirement will be that

there is a more general definition. Instead of being finite, the sets are required to have finite, non-zero measure, and so the Følner requirement will be that

,

,

analogously to the discrete case. The standard case is that of the group acting on itself by left translation, in which case the measure in question is normally assumed to be the Haar measure.

Examples

- Any finite group

trivially has a Følner sequence

trivially has a Følner sequence  for each

for each  .

.

- Consider the group of integers, acting on itself by addition. Let

consist of the integers between

consist of the integers between  and

and  . Then

. Then  consists of integers between

consists of integers between  and

and  . For large

. For large  , the symmetric difference has size

, the symmetric difference has size  , while

, while  has size

has size  . The resulting ratio is

. The resulting ratio is  , which goes to 0 as

, which goes to 0 as  gets large.

gets large.

- With the original definition of Følner sequence, a countable group has a Følner sequence if and only if it is amenable. An amenable group has a Følner sequence if and only if it is countable. A group which has a Følner sequence is countable if and only if it is amenable.

- A locally compact group has a Følner sequence (with the generalized definition) if and only if it is amenable and second countable.

Proof of amenability

We have a group  and a Følner sequence

and a Følner sequence  , and we need to define a measure

, and we need to define a measure  on

on  , which philosophically speaking says how much of

, which philosophically speaking says how much of  any subset

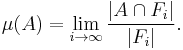

any subset  takes up. The natural definition that uses our Følner sequence would be

takes up. The natural definition that uses our Følner sequence would be

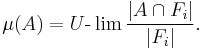

Of course, this limit doesn't necessarily exist. To overcome this technicality, we take an ultrafilter  on the natural numbers that contains intervals

on the natural numbers that contains intervals  . Then we use an ultralimit instead of the regular limit:

. Then we use an ultralimit instead of the regular limit:

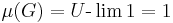

It turns out ultralimits have all the properties we need. Namely,

is a probability measure. That is,

is a probability measure. That is,  , since the ultralimit coincides with the regular limit when it exists.

, since the ultralimit coincides with the regular limit when it exists. is finitely additive. This is since ultralimits commute with addition just as regular limits do.

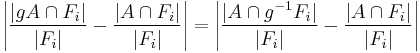

is finitely additive. This is since ultralimits commute with addition just as regular limits do. is left invariant. This is since

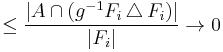

is left invariant. This is since

- by the Følner sequence definition.

References

- Erling Følner (1955). "On groups with full Banach mean value". Mathematica Scandinavica 3: 243–254. http://resolver.sub.uni-goettingen.de/purl?GDZPPN00234405X.