Enzyme

Enzymes ( /ˈɛnzaɪmz/) are proteins that catalyze (i.e., increase the rates of) chemical reactions.[1][2] In enzymatic reactions, the molecules at the beginning of the process, called substrates, are converted into different molecules, called products. Almost all chemical reactions in a biological cell need enzymes in order to occur at rates sufficient for life. Since enzymes are selective for their substrates and speed up only a few reactions from among many possibilities, the set of enzymes made in a cell determines which metabolic pathways occur in that cell.

Like all catalysts, enzymes work by lowering the activation energy (Ea‡) for a reaction, thus dramatically increasing the rate of the reaction. As a result, products are formed faster and reactions reach their equilibrium state more rapidly. Most enzyme reaction rates are millions of times faster than those of comparable un-catalyzed reactions. As with all catalysts, enzymes are not consumed by the reactions they catalyze, nor do they alter the equilibrium of these reactions. However, enzymes do differ from most other catalysts in that they are highly specific for their substrates. Enzymes are known to catalyze about 4,000 biochemical reactions.[3] A few RNA molecules called ribozymes also catalyze reactions, with an important example being some parts of the ribosome.[4][5] Synthetic molecules called artificial enzymes also display enzyme-like catalysis.[6]

Enzyme activity can be affected by other molecules. Inhibitors are molecules that decrease enzyme activity; activators are molecules that increase activity. Many drugs and poisons are enzyme inhibitors. Activity is also affected by temperature, chemical environment (e.g., pH), and the concentration of substrate. Some enzymes are used commercially, for example, in the synthesis of antibiotics. In addition, some household products use enzymes to speed up biochemical reactions (e.g., enzymes in biological washing powders break down protein or fat stains on clothes; enzymes in meat tenderizers break down proteins into smaller molecules, making the meat easier to chew).

Contents |

Etymology and history

As early as the late 17th and early 18th centuries, the digestion of meat by stomach secretions[7] and the conversion of starch to sugars by plant extracts and saliva were known. However, the mechanism by which this occurred had not been identified.[8]

In the 19th century, when studying the fermentation of sugar to alcohol by yeast, Louis Pasteur came to the conclusion that this fermentation was catalyzed by a vital force contained within the yeast cells called "ferments", which were thought to function only within living organisms. He wrote that "alcoholic fermentation is an act correlated with the life and organization of the yeast cells, not with the death or putrefaction of the cells."[9]

In 1877, German physiologist Wilhelm Kühne (1837–1900) first used the term enzyme, which comes from Greek ενζυμον, "in leaven", to describe this process.[10] The word enzyme was used later to refer to nonliving substances such as pepsin, and the word ferment was used to refer to chemical activity produced by living organisms.

In 1897, Eduard Buchner submitted his first paper on the ability of yeast extracts that lacked any living yeast cells to ferment sugar. In a series of experiments at the University of Berlin, he found that the sugar was fermented even when there were no living yeast cells in the mixture.[11] He named the enzyme that brought about the fermentation of sucrose "zymase".[12] In 1907, he received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry "for his biochemical research and his discovery of cell-free fermentation". Following Buchner's example, enzymes are usually named according to the reaction they carry out. Typically, to generate the name of an enzyme, the suffix -ase is added to the name of its substrate (e.g., lactase is the enzyme that cleaves lactose) or the type of reaction (e.g., DNA polymerase forms DNA polymers).[13]

Having shown that enzymes could function outside a living cell, the next step was to determine their biochemical nature. Many early workers noted that enzymatic activity was associated with proteins, but several scientists (such as Nobel laureate Richard Willstätter) argued that proteins were merely carriers for the true enzymes and that proteins per se were incapable of catalysis. However, in 1926, James B. Sumner showed that the enzyme urease was a pure protein and crystallized it; Sumner did likewise for the enzyme catalase in 1937. The conclusion that pure proteins can be enzymes was definitively proved by Northrop and Stanley, who worked on the digestive enzymes pepsin (1930), trypsin and chymotrypsin. These three scientists were awarded the 1946 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.[14]

This discovery that enzymes could be crystallized eventually allowed their structures to be solved by x-ray crystallography. This was first done for lysozyme, an enzyme found in tears, saliva and egg whites that digests the coating of some bacteria; the structure was solved by a group led by David Chilton Phillips and published in 1965.[15] This high-resolution structure of lysozyme marked the beginning of the field of structural biology and the effort to understand how enzymes work at an atomic level of detail.

Structures and mechanisms

Enzymes are in general globular proteins and range from just 62 amino acid residues in size, for the monomer of 4-oxalocrotonate tautomerase,[16] to over 2,500 residues in the animal fatty acid synthase.[17] A small number of RNA-based biological catalysts exist, with the most common being the ribosome; these are referred to as either RNA-enzymes or ribozymes. The activities of enzymes are determined by their three-dimensional structure.[18] However, although structure does determine function, predicting a novel enzyme's activity just from its structure is a very difficult problem that has not yet been solved.[19]

Most enzymes are much larger than the substrates they act on, and only a small portion of the enzyme (around 2–4 amino acids) is directly involved in catalysis.[20] The region that contains these catalytic residues, binds the substrate, and then carries out the reaction is known as the active site. Enzymes can also contain sites that bind cofactors, which are needed for catalysis. Some enzymes also have binding sites for small molecules, which are often direct or indirect products or substrates of the reaction catalyzed. This binding can serve to increase or decrease the enzyme's activity, providing a means for feedback regulation.

Like all proteins, enzymes are long, linear chains of amino acids that fold to produce a three-dimensional product. Each unique amino acid sequence produces a specific structure, which has unique properties. Individual protein chains may sometimes group together to form a protein complex. Most enzymes can be denatured—that is, unfolded and inactivated—by heating or chemical denaturants, which disrupt the three-dimensional structure of the protein. Depending on the enzyme, denaturation may be reversible or irreversible.

Structures of enzymes in complex with substrates or substrate analogs during a reaction may be obtained using Time resolved crystallography methods.

Specificity

Enzymes are usually very specific as to which reactions they catalyze and the substrates that are involved in these reactions. Complementary shape, charge and hydrophilic/hydrophobic characteristics of enzymes and substrates are responsible for this specificity. Enzymes can also show impressive levels of stereospecificity, regioselectivity and chemoselectivity.[21]

Some of the enzymes showing the highest specificity and accuracy are involved in the copying and expression of the genome. These enzymes have "proof-reading" mechanisms. Here, an enzyme such as DNA polymerase catalyzes a reaction in a first step and then checks that the product is correct in a second step.[22] This two-step process results in average error rates of less than 1 error in 100 million reactions in high-fidelity mammalian polymerases.[23] Similar proofreading mechanisms are also found in RNA polymerase,[24] aminoacyl tRNA synthetases[25] and ribosomes.[26]

Some enzymes that produce secondary metabolites are described as promiscuous, as they can act on a relatively broad range of different substrates. It has been suggested that this broad substrate specificity is important for the evolution of new biosynthetic pathways.[27]

"Lock and key" model

Enzymes are very specific, and it was suggested by the Nobel laureate organic chemist Emil Fischer in 1894 that this was because both the enzyme and the substrate possess specific complementary geometric shapes that fit exactly into one another.[28] This is often referred to as "the lock and key" model. However, while this model explains enzyme specificity, it fails to explain the stabilization of the transition state that enzymes achieve.

In 1958, Daniel Koshland suggested a modification to the lock and key model: since enzymes are rather flexible structures, the active site is continuously reshaped by interactions with the substrate as the substrate interacts with the enzyme.[29] As a result, the substrate does not simply bind to a rigid active site; the amino acid side-chains that make up the active site are molded into the precise positions that enable the enzyme to perform its catalytic function. In some cases, such as glycosidases, the substrate molecule also changes shape slightly as it enters the active site.[30] The active site continues to change until the substrate is completely bound, at which point the final shape and charge is determined.[31] Induced fit may enhance the fidelity of molecular recognition in the presence of competition and noise via the conformational proofreading mechanism.[32]

Mechanisms

Enzymes can act in several ways, all of which lower ΔG‡:[33]

- Lowering the activation energy by creating an environment in which the transition state is stabilized (e.g. straining the shape of a substrate—by binding the transition-state conformation of the substrate/product molecules, the enzyme distorts the bound substrate(s) into their transition state form, thereby reducing the amount of energy required to complete the transition).

- Lowering the energy of the transition state, but without distorting the substrate, by creating an environment with the opposite charge distribution to that of the transition state.

- Providing an alternative pathway. For example, temporarily reacting with the substrate to form an intermediate ES complex, which would be impossible in the absence of the enzyme.

- Reducing the reaction entropy change by bringing substrates together in the correct orientation to react. Considering ΔH‡ alone overlooks this effect.

- Increases in temperatures speed up reactions. Thus, temperature increases help the enzyme function and develop the end product even faster. However, if heated too much, the enzyme’s shape deteriorates and the enzyme becomes denatured. Some enzymes like thermolabile enzymes work best at low temperatures.

It is interesting that this entropic effect involves destabilization of the ground state,[34] and its contribution to catalysis is relatively small.[35]

Transition state stabilization

The understanding of the origin of the reduction of ΔG‡ requires one to find out how the enzymes can stabilize its transition state more than the transition state of the uncatalyzed reaction. It seems that the most effective way for reaching large stabilization is the use of electrostatic effects, in particular, when having a relatively fixed polar environment that is oriented toward the charge distribution of the transition state.[36] Such an environment does not exist in the uncatalyzed reaction in water.

Dynamics and function

The internal dynamics of enzymes has been suggested to be linked with their mechanism of catalysis.[37][38][39] Internal dynamics are the movement of parts of the enzyme's structure, such as individual amino acid residues, a group of amino acids, or even an entire protein domain. These movements occur at various time-scales ranging from femtoseconds to seconds. Networks of protein residues throughout an enzyme's structure can contribute to catalysis through dynamic motions.[40][41][42][43] This is simply seen in the kinetic scheme of the combined process, enzymatic activity and dynamics; this scheme can have several independent Michaelis-Menten-like reaction pathways that are connected through fluctuation rates. [44][45][46]

Protein motions are vital to many enzymes, but whether small and fast vibrations, or larger and slower conformational movements are more important depends on the type of reaction involved. However, although these movements are important in binding and releasing substrates and products, it is not clear if protein movements help to accelerate the chemical steps in enzymatic reactions.[47] These new insights also have implications in understanding allosteric effects and developing new medicines.

Allosteric modulation

Allosteric sites are sites on the enzyme that bind to molecules in the cellular environment. The sites form weak, noncovalent bonds with these molecules, causing a change in the conformation of the enzyme. This change in conformation translates to the active site, which then affects the reaction rate of the enzyme.[48] Allosteric interactions can both inhibit and activate enzymes and are a common way that enzymes are controlled in the body.[49]

Cofactors and coenzymes

Cofactors

Some enzymes do not need any additional components to show full activity. However, others require non-protein molecules called cofactors to be bound for activity.[50] Cofactors can be either inorganic (e.g., metal ions and iron-sulfur clusters) or organic compounds (e.g., flavin and heme). Organic cofactors can be either prosthetic groups, which are tightly bound to an enzyme, or coenzymes, which are released from the enzyme's active site during the reaction. Coenzymes include NADH, NADPH and adenosine triphosphate. These molecules transfer chemical groups between enzymes.[51]

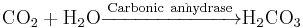

An example of an enzyme that contains a cofactor is carbonic anhydrase, and is shown in the ribbon diagram above with a zinc cofactor bound as part of its active site.[52] These tightly bound molecules are usually found in the active site and are involved in catalysis. For example, flavin and heme cofactors are often involved in redox reactions.

Enzymes that require a cofactor but do not have one bound are called apoenzymes or apoproteins. An apoenzyme together with its cofactor(s) is called a holoenzyme (this is the active form). Most cofactors are not covalently attached to an enzyme, but are very tightly bound. However, organic prosthetic groups can be covalently bound (e.g., biotin in the enzyme pyruvate carboxylase). The term "holoenzyme" can also be applied to enzymes that contain multiple protein subunits, such as the DNA polymerases; here the holoenzyme is the complete complex containing all the subunits needed for activity.

Coenzymes

Coenzymes are small organic molecules that can be loosely or tightly bound to an enzyme. Tightly bound coenzymes can be called allosteric groups. Coenzymes transport chemical groups from one enzyme to another.[53] Some of these chemicals such as riboflavin, thiamine and folic acid are vitamins (compounds that cannot be synthesized by the body and must be acquired from the diet). The chemical groups carried include the hydride ion (H-) carried by NAD or NADP+, the phosphate group carried by adenosine triphosphate, the acetyl group carried by coenzyme A, formyl, methenyl or methyl groups carried by folic acid and the methyl group carried by S-adenosylmethionine.

Since coenzymes are chemically changed as a consequence of enzyme action, it is useful to consider coenzymes to be a special class of substrates, or second substrates, which are common to many different enzymes. For example, about 700 enzymes are known to use the coenzyme NADH.[54]

Coenzymes are usually continuously regenerated and their concentrations maintained at a steady level inside the cell: for example, NADPH is regenerated through the pentose phosphate pathway and S-adenosylmethionine by methionine adenosyltransferase. This continuous regeneration means that even small amounts of coenzymes are used very intensively. For example, the human body turns over its own weight in ATP each day.[55]

Thermodynamics

As all catalysts, enzymes do not alter the position of the chemical equilibrium of the reaction. Usually, in the presence of an enzyme, the reaction runs in the same direction as it would without the enzyme, just more quickly. However, in the absence of the enzyme, other possible uncatalyzed, "spontaneous" reactions might lead to different products, because in those conditions this different product is formed faster.

Furthermore, enzymes can couple two or more reactions, so that a thermodynamically favorable reaction can be used to "drive" a thermodynamically unfavorable one. For example, the hydrolysis of ATP is often used to drive other chemical reactions.[56]

Enzymes catalyze the forward and backward reactions equally. They do not alter the equilibrium itself, but only the speed at which it is reached. For example, carbonic anhydrase catalyzes its reaction in either direction depending on the concentration of its reactants.

Nevertheless, if the equilibrium is greatly displaced in one direction, that is, in a very exergonic reaction, the reaction is in effect irreversible. Under these conditions, the enzyme will, in fact, catalyze the reaction only in the thermodynamically allowed direction.

Kinetics

Enzyme kinetics is the investigation of how enzymes bind substrates and turn them into products. The rate data used in kinetic analyses are commonly obtained from enzyme assays, where since the 90s, the dynamics of many enzymes are studied on the level of individual molecules.

In 1902 Victor Henri proposed a quantitative theory of enzyme kinetics,[57] but his experimental data were not useful because the significance of the hydrogen ion concentration was not yet appreciated. After Peter Lauritz Sørensen had defined the logarithmic pH-scale and introduced the concept of buffering in 1909[58] the German chemist Leonor Michaelis and his Canadian postdoc Maud Leonora Menten repeated Henri's experiments and confirmed his equation, which is referred to as Henri-Michaelis-Menten kinetics (termed also Michaelis-Menten kinetics).[59] Their work was further developed by G. E. Briggs and J. B. S. Haldane, who derived kinetic equations that are still widely considered today a starting point in solving enzymatic activity.[60]

The major contribution of Henri was to think of enzyme reactions in two stages. In the first, the substrate binds reversibly to the enzyme, forming the enzyme-substrate complex. This is sometimes called the Michaelis complex. The enzyme then catalyzes the chemical step in the reaction and releases the product. Note that the simple Michaelis Menten mechanism for the enzymatic activity is considered today a basic idea, where many examples show that the enzymatic activity involves structural dynamics. This is incorporated in the enzymatic mechanism while introducing several Michaelis Menten pathways that are connected with fluctuating rates [44][45][46]. Nevertheless, there is a mathematical relation connecting the behavior obtained from the basic Michaelis Menten mechanism (that was indeed proved correct in many experiments) with the generalized Michaelis Menten mechanisms involving dynamics and activity; [61] this means that the measured activity of enzymes on the level of many enzymes may be explained with the simple Michaelis-Menten equation, yet, the actual activity of enzymes is richer and involves structural dynamics.

Enzymes can catalyze up to several million reactions per second. For example, the uncatalyzed decarboxylation of orotidine 5'-monophosphate has a half life of 78 million years. However, when the enzyme orotidine 5'-phosphate decarboxylase is added, the same process takes just 25 milliseconds.[62] Enzyme rates depend on solution conditions and substrate concentration. Conditions that denature the protein abolish enzyme activity, such as high temperatures, extremes of pH or high salt concentrations, while raising substrate concentration tends to increase activity when [S] is low. To find the maximum speed of an enzymatic reaction, the substrate concentration is increased until a constant rate of product formation is seen. This is shown in the saturation curve on the right. Saturation happens because, as substrate concentration increases, more and more of the free enzyme is converted into the substrate-bound ES form. At the maximum reaction rate (Vmax) of the enzyme, all the enzyme active sites are bound to substrate, and the amount of ES complex is the same as the total amount of enzyme. However, Vmax is only one kinetic constant of enzymes. The amount of substrate needed to achieve a given rate of reaction is also important. This is given by the Michaelis-Menten constant (Km), which is the substrate concentration required for an enzyme to reach one-half its maximum reaction rate. Each enzyme has a characteristic Km for a given substrate, and this can show how tight the binding of the substrate is to the enzyme. Another useful constant is kcat, which is the number of substrate molecules handled by one active site per second.

The efficiency of an enzyme can be expressed in terms of kcat/Km. This is also called the specificity constant and incorporates the rate constants for all steps in the reaction. Because the specificity constant reflects both affinity and catalytic ability, it is useful for comparing different enzymes against each other, or the same enzyme with different substrates. The theoretical maximum for the specificity constant is called the diffusion limit and is about 108 to 109 (M−1 s−1). At this point every collision of the enzyme with its substrate will result in catalysis, and the rate of product formation is not limited by the reaction rate but by the diffusion rate. Enzymes with this property are called catalytically perfect or kinetically perfect. Example of such enzymes are triose-phosphate isomerase, carbonic anhydrase, acetylcholinesterase, catalase, fumarase, β-lactamase, and superoxide dismutase.

Michaelis-Menten kinetics relies on the law of mass action, which is derived from the assumptions of free diffusion and thermodynamically driven random collision. However, many biochemical or cellular processes deviate significantly from these conditions, because of macromolecular crowding, phase-separation of the enzyme/substrate/product, or one or two-dimensional molecular movement.[63] In these situations, a fractal Michaelis-Menten kinetics may be applied.[64][65][66][67]

Some enzymes operate with kinetics, which are faster than diffusion rates, which would seem to be impossible. Several mechanisms have been invoked to explain this phenomenon. Some proteins are believed to accelerate catalysis by drawing their substrate in and pre-orienting them by using dipolar electric fields. Other models invoke a quantum-mechanical tunneling explanation, whereby a proton or an electron can tunnel through activation barriers, although for proton tunneling this model remains somewhat controversial.[68][69] Quantum tunneling for protons has been observed in tryptamine.[70] This suggests that enzyme catalysis may be more accurately characterized as "through the barrier" rather than the traditional model, which requires substrates to go "over" a lowered energy barrier.

Inhibition

Enzyme reaction rates can be decreased by various types of enzyme inhibitors.

- Competitive inhibition

In competitive inhibition, the inhibitor and substrate compete for the enzyme (i.e., they can not bind at the same time).[72] Often competitive inhibitors strongly resemble the real substrate of the enzyme. For example, methotrexate is a competitive inhibitor of the enzyme dihydrofolate reductase, which catalyzes the reduction of dihydrofolate to tetrahydrofolate. The similarity between the structures of folic acid and this drug are shown in the figure to the right bottom. In some cases, the inhibitor can bind to a site other than the binding-site of the usual substrate and exert an allosteric effect to change the shape of the usual binding-site. For example, strychnine acts as an allosteric inhibitor of the glycine receptor in the mammalian spinal cord and brain stem. Glycine is a major post-synaptic inhibitory neurotransmitter with a specific receptor site. Strychnine binds to an alternate site that reduces the affinity of the glycine receptor for glycine, resulting in convulsions due to lessened inhibition by the glycine.[73] In competitive inhibition the maximal rate of the reaction is not changed, but higher substrate concentrations are required to reach a given maximum rate, increasing the apparent Km.

- Uncompetitive inhibition

In uncompetitive inhibition, the inhibitor cannot bind to the free enzyme, only to the ES-complex. The EIS-complex thus formed is enzymatically inactive. This type of inhibition is rare, but may occur in multimeric enzymes.

- Non-competitive inhibition

Non-competitive inhibitors can bind to the enzyme at the binding site at the same time as the substrate,but not to the active site. Both the EI and EIS complexes are enzymatically inactive. Because the inhibitor can not be driven from the enzyme by higher substrate concentration (in contrast to competitive inhibition), the apparent Vmax changes. But because the substrate can still bind to the enzyme, the Km stays the same.

- Mixed inhibition

This type of inhibition resembles the non-competitive, except that the EIS-complex has residual enzymatic activity.This type of inhibitor does not follow Michaelis-Menten equation.

In many organisms, inhibitors may act as part of a feedback mechanism. If an enzyme produces too much of one substance in the organism, that substance may act as an inhibitor for the enzyme at the beginning of the pathway that produces it, causing production of the substance to slow down or stop when there is sufficient amount. This is a form of negative feedback. Enzymes that are subject to this form of regulation are often multimeric and have allosteric binding sites for regulatory substances. Their substrate/velocity plots are not hyperbolar, but sigmoidal (S-shaped).

Irreversible inhibitors react with the enzyme and form a covalent adduct with the protein. The inactivation is irreversible. These compounds include eflornithine a drug used to treat the parasitic disease sleeping sickness.[74] Penicillin and Aspirin also act in this manner. With these drugs, the compound is bound in the active site and the enzyme then converts the inhibitor into an activated form that reacts irreversibly with one or more amino acid residues.

- Uses of inhibitors

Since inhibitors modulate the function of enzymes they are often used as drugs. A common example of an inhibitor that is used as a drug is aspirin, which inhibits the COX-1 and COX-2 enzymes that produce the inflammation messenger prostaglandin, thus suppressing pain and inflammation. However, other enzyme inhibitors are poisons. For example, the poison cyanide is an irreversible enzyme inhibitor that combines with the copper and iron in the active site of the enzyme cytochrome c oxidase and blocks cellular respiration.[75]

Biological function

Enzymes serve a wide variety of functions inside living organisms. They are indispensable for signal transduction and cell regulation, often via kinases and phosphatases.[76] They also generate movement, with myosin hydrolyzing ATP to generate muscle contraction and also moving cargo around the cell as part of the cytoskeleton.[77] Other ATPases in the cell membrane are ion pumps involved in active transport. Enzymes are also involved in more exotic functions, such as luciferase generating light in fireflies.[78] Viruses can also contain enzymes for infecting cells, such as the HIV integrase and reverse transcriptase, or for viral release from cells, like the influenza virus neuraminidase.

An important function of enzymes is in the digestive systems of animals. Enzymes such as amylases and proteases break down large molecules (starch or proteins, respectively) into smaller ones, so they can be absorbed by the intestines. Starch molecules, for example, are too large to be absorbed from the intestine, but enzymes hydrolyze the starch chains into smaller molecules such as maltose and eventually glucose, which can then be absorbed. Different enzymes digest different food substances. In ruminants, which have herbivorous diets, microorganisms in the gut produce another enzyme, cellulase, to break down the cellulose cell walls of plant fiber.[79]

Several enzymes can work together in a specific order, creating metabolic pathways. In a metabolic pathway, one enzyme takes the product of another enzyme as a substrate. After the catalytic reaction, the product is then passed on to another enzyme. Sometimes more than one enzyme can catalyze the same reaction in parallel; this can allow more complex regulation: with, for example, a low constant activity provided by one enzyme but an inducible high activity from a second enzyme.

Enzymes determine what steps occur in these pathways. Without enzymes, metabolism would neither progress through the same steps nor be fast enough to serve the needs of the cell. Indeed, a metabolic pathway such as glycolysis could not exist independently of enzymes. Glucose, for example, can react directly with ATP to become phosphorylated at one or more of its carbons. In the absence of enzymes, this occurs so slowly as to be insignificant. However, if hexokinase is added, these slow reactions continue to take place except that phosphorylation at carbon 6 occurs so rapidly that, if the mixture is tested a short time later, glucose-6-phosphate is found to be the only significant product. As a consequence, the network of metabolic pathways within each cell depends on the set of functional enzymes that are present.

Control of activity

There are five main ways that enzyme activity is controlled in the cell.

- Enzyme production (transcription and translation of enzyme genes) can be enhanced or diminished by a cell in response to changes in the cell's environment. This form of gene regulation is called enzyme induction and inhibition (see enzyme induction). For example, bacteria may become resistant to antibiotics such as penicillin because enzymes called beta-lactamases are induced that hydrolyze the crucial beta-lactam ring within the penicillin molecule. Another example are enzymes in the liver called cytochrome P450 oxidases, which are important in drug metabolism. Induction or inhibition of these enzymes can cause drug interactions.

- Enzymes can be compartmentalized, with different metabolic pathways occurring in different cellular compartments. For example, fatty acids are synthesized by one set of enzymes in the cytosol, endoplasmic reticulum and the Golgi apparatus and used by a different set of enzymes as a source of energy in the mitochondrion, through β-oxidation.[80]

- Enzymes can be regulated by inhibitors and activators. For example, the end product(s) of a metabolic pathway are often inhibitors for one of the first enzymes of the pathway (usually the first irreversible step, called committed step), thus regulating the amount of end product made by the pathways. Such a regulatory mechanism is called a negative feedback mechanism, because the amount of the end product produced is regulated by its own concentration. Negative feedback mechanism can effectively adjust the rate of synthesis of intermediate metabolites according to the demands of the cells. This helps allocate materials and energy economically, and prevents the manufacture of excess end products. The control of enzymatic action helps to maintain a stable internal environment in living organisms.

- Enzymes can be regulated through post-translational modification. This can include phosphorylation, myristoylation and glycosylation. For example, in the response to insulin, the phosphorylation of multiple enzymes, including glycogen synthase, helps control the synthesis or degradation of glycogen and allows the cell to respond to changes in blood sugar.[81] Another example of post-translational modification is the cleavage of the polypeptide chain. Chymotrypsin, a digestive protease, is produced in inactive form as chymotrypsinogen in the pancreas and transported in this form to the stomach where it is activated. This stops the enzyme from digesting the pancreas or other tissues before it enters the gut. This type of inactive precursor to an enzyme is known as a zymogen.

- Some enzymes may become activated when localized to a different environment (e.g., from a reducing (cytoplasm) to an oxidizing (periplasm) environment, high pH to low pH, etc.). For example, hemagglutinin in the influenza virus is activated by a conformational change caused by the acidic conditions, these occur when it is taken up inside its host cell and enters the lysosome.[82]

Involvement in disease

Since the tight control of enzyme activity is essential for homeostasis, any malfunction (mutation, overproduction, underproduction or deletion) of a single critical enzyme can lead to a genetic disease. The importance of enzymes is shown by the fact that a lethal illness can be caused by the malfunction of just one type of enzyme out of the thousands of types present in our bodies.

One example is the most common type of phenylketonuria. A mutation of a single amino acid in the enzyme phenylalanine hydroxylase, which catalyzes the first step in the degradation of phenylalanine, results in build-up of phenylalanine and related products. This can lead to mental retardation if the disease is untreated.[83]

Another example is when germline mutations in genes coding for DNA repair enzymes cause hereditary cancer syndromes such as xeroderma pigmentosum. Defects in these enzymes cause cancer since the body is less able to repair mutations in the genome. This causes a slow accumulation of mutations and results in the development of many types of cancer in the sufferer.

Oral administration of enzymes can be used to treat several diseases (e.g. pancreatic insufficiency and lactose intolerance). Since enzymes are proteins themselves they are potentially subject to inactivation and digestion in the gastrointestinal environment. Therefore a non-invasive imaging assay was developed to monitor gastrointestinal activity of exogenous enzymes (prolyl endopeptidase as potential adjuvant therapy for celiac disease) in vivo.[84]

Naming conventions

An enzyme's name is often derived from its substrate or the chemical reaction it catalyzes, with the word ending in -ase. Examples are lactase, alcohol dehydrogenase and DNA polymerase. This may result in different enzymes, called isozymes, with the same function having the same basic name. Isoenzymes have a different amino acid sequence and might be distinguished by their optimal pH, kinetic properties or immunologically. Isoenzyme and isozyme are homologous proteins. Furthermore, the normal physiological reaction an enzyme catalyzes may not be the same as under artificial conditions. This can result in the same enzyme being identified with two different names. For example, glucose isomerase, which is used industrially to convert glucose into the sweetener fructose, is a xylose isomerase in vivo.

The International Union of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology have developed a nomenclature for enzymes, the EC numbers; each enzyme is described by a sequence of four numbers preceded by "EC". The first number broadly classifies the enzyme based on its mechanism.

The top-level classification is[85]

- EC 1 Oxidoreductases: catalyze oxidation/reduction reactions

- EC 2 Transferases: transfer a functional group (e.g. a methyl or phosphate group)

- EC 3 Hydrolases: catalyze the hydrolysis of various bonds

- EC 4 Lyases: cleave various bonds by means other than hydrolysis and oxidation

- EC 5 Isomerases: catalyze isomerization changes within a single molecule

- EC 6 Ligases: join two molecules with covalent bonds.

According to the naming conventions, enzymes are generally classified into six main family classes and many sub-family classes. Some web-servers, e.g., EzyPred [86] and bioinformatics tools have been developed to predict which main family class [87] and sub-family class [88] [89] an enzyme molecule belongs to according to its sequence information alone via the pseudo amino acid composition.

Industrial applications

Enzymes are used in the chemical industry and other industrial applications when extremely specific catalysts are required. However, enzymes in general are limited in the number of reactions they have evolved to catalyze and also by their lack of stability in organic solvents and at high temperatures. As a consequence, protein engineering is an active area of research and involves attempts to create new enzymes with novel properties, either through rational design or in vitro evolution.[90][91] These efforts have begun to be successful, and a few enzymes have now been designed "from scratch" to catalyze reactions that do not occur in nature.[92]

| Application | Enzymes used | Uses |

| Food processing | Amylases from fungi and plants | Production of sugars from starch, such as in making high-fructose corn syrup.[93] In baking, catalyze breakdown of starch in the flour to sugar. Yeast fermentation of sugar produces the carbon dioxide that raises the dough. |

| Proteases | Biscuit manufacturers use them to lower the protein level of flour. | |

| Baby foods | Trypsin | To predigest baby foods |

| Brewing industry | Enzymes from barley are released during the mashing stage of beer production. | They degrade starch and proteins to produce simple sugar, amino acids and peptides that are used by yeast for fermentation. |

| Industrially produced barley enzymes | Widely used in the brewing process to substitute for the natural enzymes found in barley. | |

| Amylase, glucanases, proteases | Split polysaccharides and proteins in the malt. | |

| Betaglucanases and arabinoxylanases | Improve the wort and beer filtration characteristics. | |

| Amyloglucosidase and pullulanases | Low-calorie beer and adjustment of fermentability. | |

| Proteases | Remove cloudiness produced during storage of beers. | |

| Acetolactatedecarboxylase (ALDC) | Increases fermentation efficiency by reducing diacetyl formation.[94] | |

| Fruit juices | Cellulases, pectinases | Clarify fruit juices. |

| Dairy industry | Rennin, derived from the stomachs of young ruminant animals (like calves and lambs) | Manufacture of cheese, used to hydrolyze protein |

| Microbially produced enzyme | Now finding increasing use in the dairy industry | |

| Lipases | Is implemented during the production of Roquefort cheese to enhance the ripening of the blue-mold cheese. | |

| Lactases | Break down lactose to glucose and galactose. | |

| Meat tenderizers | Papain | To soften meat for cooking |

| Starch industry | Amylases, amyloglucosideases and glucoamylases | Converts starch into glucose and various syrups. |

| Glucose isomerase | Converts glucose into fructose in production of high-fructose syrups from starchy materials. These syrups have enhanced sweetening properties and lower calorific values than sucrose for the same level of sweetness. | |

| Paper industry | Amylases, Xylanases, Cellulases and ligninases | Degrade starch to lower viscosity, aiding sizing and coating paper. Xylanases reduce bleach required for decolorizing; cellulases smooth fibers, enhance water drainage, and promote ink removal; lipases reduce pitch and lignin-degrading enzymes remove lignin to soften paper. |

| Biofuel industry | Cellulases | Used to break down cellulose into sugars that can be fermented (see cellulosic ethanol) |

| Ligninases | Use of lignin waste | |

| Biological detergent | Primarily proteases, produced in an extracellular form from bacteria | Used for presoak conditions and direct liquid applications helping with removal of protein stains from clothes |

| Amylases | Detergents for machine dish washing to remove resistant starch residues | |

| Lipases | Used to assist in the removal of fatty and oily stains | |

| Cellulases | Used in biological fabric conditioners | |

| Contact lens cleaners | Proteases | To remove proteins on contact lens to prevent infections |

| Rubber industry | Catalase | To generate oxygen from peroxide to convert latex into foam rubber |

| Photographic industry | Protease (ficin) | Dissolve gelatin off scrap film, allowing recovery of its silver content. |

| Molecular biology | Restriction enzymes, DNA ligase and polymerases | Used to manipulate DNA in genetic engineering, important in pharmacology, agriculture and medicine. Essential for restriction digestion and the polymerase chain reaction. Molecular biology is also important in forensic science. |

See also

- List of enzymes

- Enzyme product

- Enzyme substrate

- Enzyme catalysis

- Enzyme assay

- Protein dynamics

- The Proteolysis Map

- RNA Biocatalysis

- SUMO enzymes

- Ki Database

- Proteonomics and protein engineering

- Immobilized enzyme

- Kinetic Perfection

- Enzyme engineering

References

- ^ Smith AL (Ed) (1997). Oxford dictionary of biochemistry and molecular biology. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-854768-4.

- ^ Grisham, Charles M.; Reginald H. Garrett (1999). Biochemistry. Philadelphia: Saunders College Pub. pp. 426–7. ISBN 0-03-022318-0.

- ^ Bairoch A. (2000). "The ENZYME database in 2000" (PDF). Nucleic Acids Res 28 (1): 304–5. doi:10.1093/nar/28.1.304. PMC 102465. PMID 10592255. http://www.expasy.org/NAR/enz00.pdf.

- ^ Lilley D (2005). "Structure, folding and mechanisms of ribozymes". Curr Opin Struct Biol 15 (3): 313–23. doi:10.1016/j.sbi.2005.05.002. PMID 15919196.

- ^ Cech T (2000). "Structural biology. The ribosome is a ribozyme". Science 289 (5481): 878–9. doi:10.1126/science.289.5481.878. PMID 10960319.

- ^ Groves JT (1997). "Artificial enzymes. The importance of being selective". Nature 389 (6649): 329–30. doi:10.1038/38602. PMID 9311771.

- ^ de Réaumur, RAF (1752). "Observations sur la digestion des oiseaux". Histoire de l'academie royale des sciences 1752: 266, 461.

- ^ Williams, H. S. (1904) A History of Science: in Five Volumes. Volume IV: Modern Development of the Chemical and Biological Sciences Harper and Brothers (New York) Accessed 4 April 2007

- ^ Dubos J. (1951). "Louis Pasteur: Free Lance of Science, Gollancz. Quoted in Manchester K. L. (1995) Louis Pasteur (1822–1895)—chance and the prepared mind". Trends Biotechnol 13 (12): 511–5. doi:10.1016/S0167-7799(00)89014-9. PMID 8595136.

- ^ Kühne coined the word "enzyme" in: W. Kühne (1877) "Über das Verhalten verschiedener organisirter und sog. ungeformter Fermente" (On the behavior of various organized and so-called unformed ferments), Verhandlungen des naturhistorisch-medicinischen Vereins zu Heidelberg, new series, vol. 1, no. 3, pages 190–193. The relevant passage occurs on page 190: "Um Missverständnissen vorzubeugen und lästige Umschreibungen zu vermeiden schlägt Vortragender vor, die ungeformten oder nicht organisirten Fermente, deren Wirkung ohne Anwesenheit von Organismen und ausserhalb derselben erfolgen kann, als Enzyme zu bezeichnen." (Translation: In order to obviate misunderstandings and avoid cumbersome periphrases, [the author, a university lecturer] suggests designating as "enzymes" the unformed or not organized ferments, whose action can occur without the presence of organisms and outside of the same.)

- ^ Nobel Laureate Biography of Eduard Buchner at http://nobelprize.org. Retrieved 4 April 2007.

- ^ Text of Eduard Buchner's 1907 Nobel lecture at http://nobelprize.org. Retrieved 4 April 2007.

- ^ The naming of enzymes by adding the suffix "-ase" to the substrate on which the enzyme acts, has been traced to French scientist Émile Duclaux (1840–1904), who intended to honor the discoverers of diastase – the first enzyme to be isolated – by introducing this practice in his book Traité de Microbiologie, vol. 2 (Paris, France: Masson and Co., 1899). See Chapter 1, especially page 9.

- ^ 1946 Nobel prize for Chemistry laureates at http://nobelprize.org. Retrieved 4 April 2007.

- ^ Blake CC, Koenig DF, Mair GA, North AC, Phillips DC, Sarma VR. (1965). "Structure of hen egg-white lysozyme. A three-dimensional Fourier synthesis at 2 Angstrom resolution". Nature 22 (206): 757–61. doi:10.1038/206757a0. PMID 5891407.

- ^ Chen LH, Kenyon GL, Curtin F, Harayama S, Bembenek ME, Hajipour G, Whitman CP (1992). "4-Oxalocrotonate tautomerase, an enzyme composed of 62 amino acid residues per monomer". J. Biol. Chem. 267 (25): 17716–21. PMID 1339435.

- ^ Smith S (1 December 1994). "The animal fatty acid synthase: one gene, one polypeptide, seven enzymes". FASEB J. 8 (15): 1248–59. PMID 8001737.

- ^ Anfinsen C.B. (1973). "Principles that Govern the Folding of Protein Chains". Science 181 (4096): 223–30. doi:10.1126/science.181.4096.223. PMID 4124164.

- ^ Dunaway-Mariano D (2008). "Enzyme function discovery". Structure 16 (11): 1599–600. doi:10.1016/j.str.2008.10.001. PMID 19000810.

- ^ The Catalytic Site Atlas at The European Bioinformatics Institute. Retrieved 4 April 2007.

- ^ Jaeger KE, Eggert T. (2004). "Enantioselective biocatalysis optimized by directed evolution". Curr Opin Biotechnol. 15 (4): 305–13. doi:10.1016/j.copbio.2004.06.007. PMID 15358000.

- ^ Shevelev IV, Hubscher U. (2002). "The 3' 5' exonucleases". Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 3 (5): 364–76. doi:10.1038/nrm804. PMID 11988770.

- ^ Tymoczko, John L.; Stryer Berg Tymoczko; Stryer, Lubert; Berg, Jeremy Mark (2002). Biochemistry. San Francisco: W.H. Freeman. ISBN 0-7167-4955-6.

- ^ Zenkin N, Yuzenkova Y, Severinov K. (2006). "Transcript-assisted transcriptional proofreading". Science. 313 (5786): 518–20. doi:10.1126/science.1127422. PMID 16873663.

- ^ Ibba M, Soll D. (2000). "Aminoacyl-tRNA synthesis". Annu Rev Biochem. 69: 617–50. doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.617. PMID 10966471.

- ^ Rodnina MV, Wintermeyer W. (2001). "Fidelity of aminoacyl-tRNA selection on the ribosome: kinetic and structural mechanisms". Annu Rev Biochem. 70: 415–35. doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.415. PMID 11395413.

- ^ Firn, Richard. "The Screening Hypothesis – a new explanation of secondary product diversity and function". Archived from the original on 2006-05-16. http://web.archive.org/web/20060516035537/http://www-users.york.ac.uk/~drf1/rdf_sp1.htm. Retrieved 2006-10-11.

- ^ Fischer E. (1894). "Einfluss der Configuration auf die Wirkung der Enzyme". Ber. Dt. Chem. Ges. 27 (3): 2985–93. doi:10.1002/cber.18940270364. http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k90736r/f364.chemindefer.

- ^ Koshland D. E. (1958). "Application of a Theory of Enzyme Specificity to Protein Synthesis". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 44 (2): 98–104. doi:10.1073/pnas.44.2.98. PMC 335371. PMID 16590179. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=335371.

- ^ Vasella A, Davies GJ, Bohm M. (2002). "Glycosidase mechanisms". Curr Opin Chem Biol. 6 (5): 619–29. doi:10.1016/S1367-5931(02)00380-0. PMID 12413546.

- ^ Boyer, Rodney (2002) [2002]. "6". Concepts in Biochemistry (2nd ed.). New York, Chichester, Weinheim, Brisbane, Singapore, Toronto.: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.. pp. 137–8. ISBN 0-470-00379-0. OCLC 51720783.

- ^ Savir Y & Tlusty T (2007). Scalas, Enrico. ed. "Conformational proofreading: the impact of conformational changes on the specificity of molecular recognition". PLoS ONE 2 (5): e468. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0000468. PMC 1868595. PMID 17520027. http://www.weizmann.ac.il/complex/tlusty/papers/PLoSONE2007.pdf.

- ^ Fersht, Alan (1985). Enzyme structure and mechanism. San Francisco: W.H. Freeman. pp. 50–2. ISBN 0-7167-1615-1.

- ^ Jencks, William P. (1987). Catalysis in chemistry and enzymology. Mineola, N.Y: Dover. ISBN 0-486-65460-5.

- ^ Villa J, Strajbl M, Glennon TM, Sham YY, Chu ZT, Warshel A (2000). "How important are entropic contributions to enzyme catalysis?". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97 (22): 11899–904. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.22.11899. PMC 17266. PMID 11050223. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=17266.

- ^ Warshel A, Sharma PK, Kato M, Xiang Y, Liu H, Olsson MH (2006). "Electrostatic basis for enzyme catalysis". Chem. Rev. 106 (8): 3210–35. doi:10.1021/cr0503106. PMID 16895325.

- ^ Eisenmesser EZ, Bosco DA, Akke M, Kern D (2002). "Enzyme dynamics during catalysis". Science 295 (5559): 1520–3. doi:10.1126/science.1066176. PMID 11859194.

- ^ Agarwal PK (2005). "Role of protein dynamics in reaction rate enhancement by enzymes". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127 (43): 15248–56. doi:10.1021/ja055251s. PMID 16248667.

- ^ Eisenmesser EZ, Millet O, Labeikovsky W (2005). "Intrinsic dynamics of an enzyme underlies catalysis". Nature 438 (7064): 117–21. doi:10.1038/nature04105. PMID 16267559.

- ^ Yang LW, Bahar I (5 June 2005). "Coupling between catalytic site and collective dynamics: A requirement for mechanochemical activity of enzymes". Structure 13 (6): 893–904. doi:10.1016/j.str.2005.03.015. PMC 1489920. PMID 15939021. http://www.cell.com/structure/abstract/S0969-2126%2805%2900167-X.

- ^ Agarwal PK, Billeter SR, Rajagopalan PT, Benkovic SJ, Hammes-Schiffer S. (5 March 2002). "Network of coupled promoting motions in enzyme catalysis". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 99 (5): 2794–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.052005999. PMC 122427. PMID 11867722. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=122427.

- ^ Agarwal PK, Geist A, Gorin A (2004). "Protein dynamics and enzymatic catalysis: investigating the peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerization activity of cyclophilin A". Biochemistry 43 (33): 10605–18. doi:10.1021/bi0495228. PMID 15311922.

- ^ Tousignant A, Pelletier JN. (2004). "Protein motions promote catalysis". Chem Biol. 11 (8): 1037–42. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.06.007. PMID 15324804.

- ^ a b Flomenbom O, Velonia K, Loos D et al. (2005). "Stretched exponential decay and correlations in the catalytic activity of fluctuating single lipase molecules". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102 (7): 2368–2372. doi:10.1073/pnas.0409039102. ISBN 0409039102. PMC 548972. PMID 15695587. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=548972.

- ^ a b English BP, Min W, van Oijen AM et al. (2006). "Ever-fluctuating single enzyme molecules: Michaelis-Menten equation revisited". Nature Chem. Biol. 2 (2): 87–94. doi:10.1038/nchembio759. PMID 16415859.

- ^ a b Lu H, Xun L, Xie X S (1998). "Single-molecule enzymatic dynamics". Science 282 (5395): 1877–1882. doi:10.1126/science.282.5395.1877. PMID 9836635.

- ^ Olsson, MH; Parson, WW; Warshel, A (2006). "Dynamical Contributions to Enzyme Catalysis: Critical Tests of A Popular Hypothesis". Chem. Rev. 106 (5): 1737–56. doi:10.1021/cr040427e. PMID 16683752.

- ^ Neet KE (1995). "Cooperativity in enzyme function: equilibrium and kinetic aspects". Meth. Enzymol.. Methods in Enzymology 249: 519–67. doi:10.1016/0076-6879(95)49048-5. ISBN 9780121821500. PMID 7791626.

- ^ Changeux JP, Edelstein SJ (2005). "Allosteric mechanisms of signal transduction". Science 308 (5727): 1424–8. doi:10.1126/science.1108595. PMID 15933191.

- ^ de Bolster, M.W.G. (1997). "Glossary of Terms Used in Bioinorganic Chemistry: Cofactor". International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry. http://www.chem.qmul.ac.uk/iupac/bioinorg/CD.html#34. Retrieved 2007-10-30.

- ^ de Bolster, M.W.G. (1997). "Glossary of Terms Used in Bioinorganic Chemistry: Coenzyme". International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry. http://www.chem.qmul.ac.uk/iupac/bioinorg/CD.html#33. Retrieved 2007-10-30.

- ^ Fisher Z, Hernandez Prada JA, Tu C, Duda D, Yoshioka C, An H, Govindasamy L, Silverman DN and McKenna R. (2005). "Structural and kinetic characterization of active-site histidine as a proton shuttle in catalysis by human carbonic anhydrase II". Biochemistry. 44 (4): 1097–115. doi:10.1021/bi0480279. PMID 15667203.

- ^ Wagner, Arthur L. (1975). Vitamins and Coenzymes. Krieger Pub Co. ISBN 0-88275-258-8.

- ^ BRENDA The Comprehensive Enzyme Information System. Retrieved 4 April 2007.

- ^ Törnroth-Horsefield S, Neutze R (2008). "Opening and closing the metabolite gate". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105 (50): 19565–6. doi:10.1073/pnas.0810654106. PMC 2604989. PMID 19073922. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2604989.

- ^ Ferguson, S. J.; Nicholls, David; Ferguson, Stuart (2002). Bioenergetics 3 (3rd ed.). San Diego: Academic. ISBN 0-12-518121-3.

- ^ Henri, V. (1902). "Theorie generale de l'action de quelques diastases". Compt. Rend. Hebd. Acad. Sci. Paris 135: 916–9.

- ^ Sørensen,P.L. (1909). "Enzymstudien {II}. Über die Messung und Bedeutung der Wasserstoffionenkonzentration bei enzymatischen Prozessen". Biochem. Z. 21: 131–304.

- ^ Michaelis L., Menten M. (1913). "Die Kinetik der Invertinwirkung". Biochem. Z. 49: 333–369. English translation. Retrieved 6 April 2007.

- ^ Briggs G. E., Haldane J. B. S. (1925). "A note on the kinetics of enzyme action". Biochem. J. 19 (2): 339–339. PMC 1259181. PMID 16743508. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1259181.

- ^ Xue X, Liu F, Ou-Yang ZC (2006). "Single molecule Michaelis-Menten equation beyond quasistatic disorder". Phys. Rev. E 74 (3): 030902. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.74.030902. PMID 17025584.

- ^ Radzicka A, Wolfenden R. (1995). "A proficient enzyme". Science 267 (5194): 90–931. doi:10.1126/science.7809611. PMID 7809611.

- ^ Ellis RJ (2001). "Macromolecular crowding: obvious but underappreciated". Trends Biochem. Sci. 26 (10): 597–604. doi:10.1016/S0968-0004(01)01938-7. PMID 11590012.

- ^ Kopelman R (1988). "Fractal Reaction Kinetics". Science 241 (4873): 1620–26. doi:10.1126/science.241.4873.1620. PMID 17820893.

- ^ Savageau MA (1995). "Michaelis-Menten mechanism reconsidered: implications of fractal kinetics". J. Theor. Biol. 176 (1): 115–24. doi:10.1006/jtbi.1995.0181. PMID 7475096.

- ^ Schnell S, Turner TE (2004). "Reaction kinetics in intracellular environments with macromolecular crowding: simulations and rate laws". Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 85 (2–3): 235–60. doi:10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2004.01.012. PMID 15142746.

- ^ Xu F, Ding H (2007). "A new kinetic model for heterogeneous (or spatially confined) enzymatic catalysis: Contributions from the fractal and jamming (overcrowding) effects". Appl. Catal. A: Gen. 317 (1): 70–81. doi:10.1016/j.apcata.2006.10.014.

- ^ Garcia-Viloca M., Gao J., Karplus M., Truhlar D. G. (2004). "How enzymes work: analysis by modern rate theory and computer simulations". Science 303 (5655): 186–95. doi:10.1126/science.1088172. PMID 14716003.

- ^ Olsson M. H., Siegbahn P. E., Warshel A. (2004). "Simulations of the large kinetic isotope effect and the temperature dependence of the hydrogen atom transfer in lipoxygenase". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126 (9): 2820–8. doi:10.1021/ja037233l. PMID 14995199.

- ^ Masgrau L., Roujeinikova A., Johannissen L. O., Hothi P., Basran J., Ranaghan K. E., Mulholland A. J., Sutcliffe M. J., Scrutton N. S., Leys D. (2006). "Atomic Description of an Enzyme Reaction Dominated by Proton Tunneling". Science 312 (5771): 237–41. doi:10.1126/science.1126002. PMID 16614214.

- ^ Cleland, W.W. (1963). "The Kinetics of Enzyme-catalyzed Reactions with two or more Substrates or Products 2. {I}nhibition: Nomenclature and Theory". Biochim. Biophys. Acta 67: 173–87.

- ^ Price, NC. (1979). "What is meant by 'competitive inhibition'?". Trends in Biochemical Sciences 4: pN272.

- ^ Dick, Ronald M. (2011). "Chapter 2. Pharmacodynamics: The Study of Drug Action". In Ouellette, Richard G.; Joyce, Joseph A.. Pharmacology for Nurse Anesthesiology. Jones & Bartlett Learning. ISBN 9780763786076.

- ^ R Poulin; Lu, L; Ackermann, B; Bey, P; Pegg, AE (1992-01-05). "Mechanism of the irreversible inactivation of mouse ornithine decarboxylase by alpha-difluoromethylornithine. Characterization of sequences at the inhibitor and coenzyme binding sites". Journal of Biological Chemistry 267 (1): 150–8. PMID 1730582.

- ^ Yoshikawa S and Caughey WS. (15 May 1990). "Infrared evidence of cyanide binding to iron and copper sites in bovine heart cytochrome c oxidase. Implications regarding oxygen reduction". J Biol Chem. 265 (14): 7945–58. PMID 2159465.

- ^ Hunter T. (1995). "Protein kinases and phosphatases: the yin and yang of protein phosphorylation and signaling". Cell. 80 (2): 225–36. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(95)90405-0. PMID 7834742.

- ^ Berg JS, Powell BC, Cheney RE (1 April 2001). "A millennial myosin census". Mol. Biol. Cell 12 (4): 780–94. PMC 32266. PMID 11294886. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=32266.

- ^ Meighen EA (1 March 1991). "Molecular biology of bacterial bioluminescence". Microbiol. Rev. 55 (1): 123–42. PMC 372803. PMID 2030669. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=372803.

- ^ Mackie RI, White BA (1 October 1990). "Recent advances in rumen microbial ecology and metabolism: potential impact on nutrient output". J. Dairy Sci. 73 (10): 2971–95. doi:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(90)78986-2. PMID 2178174.

- ^ Faergeman NJ, Knudsen J (1997). "Role of long-chain fatty acyl-CoA esters in the regulation of metabolism and in cell signalling". Biochem. J. 323 (Pt 1): 1–12. PMC 1218279. PMID 9173866. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1218279.

- ^ Doble B. W., Woodgett J. R. (2003). "GSK-3: tricks of the trade for a multi-tasking kinase". J. Cell. Sci. 116 (Pt 7): 1175–86. doi:10.1242/jcs.00384. PMC 3006448. PMID 12615961. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3006448.

- ^ Carr C. M., Kim P. S. (2003). "A spring-loaded mechanism for the conformational change of influenza hemagglutinin". Cell 73 (4): 823–32. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(93)90260-W. PMID 8500173.

- ^ Phenylketonuria: NCBI Genes and Disease. Retrieved 4 April 2007.

- ^ Fuhrmann G, Leroux JC (2011). "In vivo fluorescence imaging of exogenous enzyme activity in the gastrointestinal tract". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108 (22): 9032–9037. doi:10.1073/pnas.1100285108.

- ^ The complete nomenclature can be browsed at Enzyme Nomenclature. Recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee of the International Union of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology on the Nomenclature and Classification of Enzymes by the Reactions they Catalyse. Nomenclature Committee of the International Union of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology (NC-IUBMB)

- ^ Shen, HB; Chou, KC (2007). "EzyPred: A top-down approach for predicting enzyme functional classes and subclasses". Biochemical and biophysical research communications 364 (1): 53–9. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.09.098. PMID 17931599.

- ^ Qiu, JD; Huang, JH; Shi, SP; Liang, RP (2010). "Using the concept of Chou's pseudo amino acid composition to predict enzyme family classes: An approach with support vector machine based on discrete wavelet transform". Protein and peptide letters 17 (6): 715–22. doi:10.2174/092986610791190372. PMID 19961429.

- ^ Zhou, X. B., Chen, C., Li, Z. C. & Zou, X. Y. (2007). "Using Chou's amphiphilic pseudo-amino acid composition and support vector machine for prediction of enzyme subfamily classes". Journal of Theoretical Biology 248 (3): 546–551. doi:10.1016/j.jtbi.2007.06.001. PMID 17628605.

- ^ Chou, K. C. (2005). "Using amphiphilic pseudo amino acid composition to predict enzyme subfamily classes". Bioinformatics 21 (1): 10–19. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/bth466. PMID 15308540.

- ^ Renugopalakrishnan V, Garduno-Juarez R, Narasimhan G, Verma CS, Wei X, Li P. (2005). "Rational design of thermally stable proteins: relevance to bionanotechnology". J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 5 (11): 1759–1767. doi:10.1166/jnn.2005.441. PMID 16433409.

- ^ Hult K, Berglund P. (2003). "Engineered enzymes for improved organic synthesis". Curr Opin Biotechnol. 14 (4): 395–400. doi:10.1016/S0958-1669(03)00095-8. PMID 12943848.

- ^ Jiang L, Althoff EA, Clemente FR (2008). "De novo computational design of retro-aldol enzymes". Science 319 (5868): 1387–91. doi:10.1126/science.1152692. PMID 18323453.

- ^ Guzmán-Maldonado H, Paredes-López O (1995). "Amylolytic enzymes and products derived from starch: a review". Critical reviews in food science and nutrition 35 (5): 373–403. doi:10.1080/10408399509527706. PMID 8573280.

- ^ Dulieu C, Moll M, Boudrant J, Poncelet D (2000). "Improved performances and control of beer fermentation using encapsulated alpha-acetolactate decarboxylase and modeling". Biotechnology progress 16 (6): 958–65. doi:10.1021/bp000128k. PMID 11101321.

Further reading

|

Etymology and history

Enzyme structure and mechanism

Thermodynamics

|

Kinetics and inhibition

Function and control of enzymes in the cell

Enzyme-naming conventions

Industrial applications

|

External links

- Structure/Function of Enzymes, Web tutorial on enzyme structure and function.

- Enzymes in diagnosis Role of enzymes in diagnosis of diseases.

- Enzyme spotlight Monthly feature at the European Bioinformatics Institute on a selected enzyme.

- AMFEP, Association of Manufacturers and Formulators of Enzyme Products

- BRENDA database, a comprehensive compilation of information and literature references about all known enzymes; requires payment by commercial users.

- Enzyme Structures Database links to the known 3-D structure data of enzymes in the Protein Data Bank.

- ExPASy enzyme database, links to Swiss-Prot sequence data, entries in other databases and to related literature searches.

- KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes Graphical and hypertext-based information on biochemical pathways and enzymes.

- [1] enzyme database

- MACiE database of enzyme reaction mechanisms.

- MetaCyc database of enzymes and metabolic pathways

- Face-to-Face Interview with Sir John Cornforth who was awarded a Nobel Prize for work on stereochemistry of enzyme-catalyzed reactions Freeview video by the Vega Science Trust

- Sigma Aldrich Enzyme Assays by Enzyme Name—Hundreds of assays sorted by enzyme name.

- Bugg TD (2001). "The development of mechanistic enzymology in the 20th century". Nat Prod Rep 18 (5): 465–93. doi:10.1039/b009205n. PMID 11699881.

|

|

|||||

|

|||||||||||

(in

(in  (in

(in