Enumeration

In mathematics and theoretical computer science, the broadest and most abstract definition of an enumeration of a set is an exact listing of all of its elements (perhaps with repetition). The restrictions imposed on the type of list used depend on the branch of mathematics and the context in which one is working. In more specific settings, this notion of enumeration encompasses the two different types of listing: one where there is a natural ordering and one where the ordering is more nebulous. These two different kinds of enumerations correspond to a procedure for listing all members of the set in some definite sequence, or a count of objects of a specified kind, respectively. While the two kinds of enumeration often overlap in most natural situations, they can assume very different meanings in certain contexts.

Contents |

Enumeration in combinatorics

In combinatorics, enumeration means counting, i.e., determining the exact number of elements of finite sets, usually grouped into infinite families, such as the family of sets each consisting of all permutations of some finite set. There are flourishing subareas in many branches of mathematics concerned with enumerating in this sense objects of special kinds. For instance, in partition enumeration and graph enumeration the objective is to count partitions or graphs that meet certain conditions.

Enumeration in set theory

In set theory, the notion of enumeration has a broader sense, and does not require the set being enumerated to be finite.

Enumeration as listing

When an enumeration is used in an ordered list context, we impose some sort of ordering structure requirement on the index set. While we can make the requirements on the ordering quite lax in order to allow for great generality, the most natural and common prerequisite is that the index set be well-ordered. According to this characterization, an ordered enumeration is defined to be a surjection with a well-ordered domain. This definition is natural in the sense that a given well-ordering on the index set provides a unique way to list the next element given a partial enumeration.

Enumeration in countable vs. uncountable context

The most common use of enumeration in set theory occurs in the context where infinite sets are separated into those that are countable and those that are not. In this case, an enumeration is merely an enumeration with domain ω, the ordinal of the natural numbers. This definition can also be stated as follows:

- As a surjective mapping from

(the natural numbers) to S (i.e., every element of S is the image of at least one natural number). This definition is especially suitable to questions of computability and elementary set theory.

(the natural numbers) to S (i.e., every element of S is the image of at least one natural number). This definition is especially suitable to questions of computability and elementary set theory.

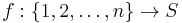

We may also define it differently when working with finite sets. In this case an enumeration may be defined as follows:

- As a bijective mapping from S to an initial segment of the natural numbers. This definition is especially suitable to combinatorial questions and finite sets; then the initial segment is {1,2,...,n} for some n which is the cardinality of S.

In the first definition it varies whether the mapping is also required to be injective (i.e., every element of S is the image of exactly one natural number), and/or allowed to be partial (i.e., the mapping is defined only for some natural numbers). In some applications (especially those concerned with computability of the set S), these differences are of little importance, because one is concerned only with the mere existence of some enumeration, and an enumeration according to a liberal definition will generally imply that enumerations satisfying stricter requirements also exist.

Enumeration of finite sets obviously requires that either non-injectivity or partiality is accepted, and in contexts where finite sets may appear one or both of these are inevitably present.

Examples

- The natural numbers are enumerable by the function f(x) = x. In this case

is simply the identity function.

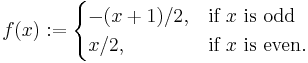

is simply the identity function.  , the set of integers is enumerable by

, the set of integers is enumerable by

is a bijection since every natural number corresponds to exactly one integer. The following table gives the first few values of this enumeration:

is a bijection since every natural number corresponds to exactly one integer. The following table gives the first few values of this enumeration:

| x | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ƒ(x) | 0 | −1 | 1 | −2 | 2 | −3 | 3 | −4 | 4 |

- All finite sets are enumerable. Let S be a finite set with n elements and let K = {1,2,...,n}. Select any element s in S and assign ƒ(n) = s. Now set S' = S − {s} (where − denotes set difference). Select any element s' ∈ S' and assign ƒ(n − 1) = s. Continue this process until all elements of the set have been assigned a natural number. Then

is an enumeration of S.

is an enumeration of S.

- The real numbers have no countable enumeration as proved by Cantor's diagonal argument and Cantor's first uncountability proof.

Properties

- There exists an enumeration for a set (in this sense) if and only if the set is countable.

- If a set is enumerable it will have an uncountable infinity of different enumerations, except in the degenerate cases of the empty set or (depending on the precise definition) sets with one element. However, if one requires enumerations to be injective and allows only a limited form of partiality such that if ƒ(n) is defined then ƒ(m) must be defined for all m < n, then a finite set of N elements has exactly N! enumerations.

- An enumeration e of a set S with domain

induces a well-order ≤ on that set defined by s ≤ t if and only if min e−1(s) ≤ min e−1(t). Although the order may have little to do with the underlying set, it is useful when some order of the set is necessary.

induces a well-order ≤ on that set defined by s ≤ t if and only if min e−1(s) ≤ min e−1(t). Although the order may have little to do with the underlying set, it is useful when some order of the set is necessary.

Ordinal enumeration

In set theory, there is a more general notion of an enumeration than the characterization requiring the domain of the listing function to be an initial segment of the Natural numbers where the domain of the enumerating function can assume any ordinal. Under this definition, an enumeration of a set S is any surjection from an ordinal α onto S. The more restrictive version of enumeration mentioned before is the special case where α is a finite ordinal or the first limit ordinal ω. This more generalized version extends the aforementioned definition to encompass transfinite listings.

Under this definition, the first uncountable ordinal  can be enumerated by the identity function on

can be enumerated by the identity function on  so that these two notions do not coincide. More generally, it is a theorem of ZF that any well-ordered set can be enumerated under this characterization so that it coincides up to relabeling with the generalized listing enumeration. If one also assumes the Axiom of Choice, then all sets can be enumerated so that it coincides up to relabeling with the most general form of enumerations.

so that these two notions do not coincide. More generally, it is a theorem of ZF that any well-ordered set can be enumerated under this characterization so that it coincides up to relabeling with the generalized listing enumeration. If one also assumes the Axiom of Choice, then all sets can be enumerated so that it coincides up to relabeling with the most general form of enumerations.

Since set theorists work with infinite sets of arbitrarily large cardinalities, the default definition among this group of mathematicians of an enumeration of a set tends to be any arbitrary α-sequence exactly listing all of its elements. Indeed, in Jech's book, which is a common reference for set theorists, an enumeration is defined to be exactly this. Therefore, in order to avoid ambiguity, one may use the term finitely enumerable or denumerable to denote one of the corresponding types of distinguished countable enumerations.

Enumeration as comparison of cardinalities

Formally, the most inclusive definition of an enumeration of a set S is any surjection from an arbitrary index set I onto S. In this broad context, every set S can be trivially enumerated by the identity function from S onto itself. If one does not assume the axiom of choice or one of its variants, S need not have any well-ordering. Even if one does assume the axiom of choice, S need not have any natural well-ordering.

This general definition therefore lends itself to a counting notion where we are interested in "how many" rather than "in what order." In practice, this broad meaning of enumeration is often used to compare the relative sizes or cardinalities of different sets. If one works in Zermelo-Fraenkel set theory without the axiom of choice, one may want to impose the additional restriction that an enumeration must also be injective (without repetition) since in this theory, the existence of a surjection from I onto S need not imply the existence of an injection from S into I.

Enumeration in computability theory

In computability theory one often considers countable enumerations with the added requirement that the mapping from  to the enumerated set must be computable. The set being enumerated is then called recursively enumerable (or computably enumerable in more contemporary language), referring to the use of recursion theory in formalizations of what it means for the map to be computable.

to the enumerated set must be computable. The set being enumerated is then called recursively enumerable (or computably enumerable in more contemporary language), referring to the use of recursion theory in formalizations of what it means for the map to be computable.

In this sense, a subset of Natural numbers is computably enumerable if it is the range of a computable function. In this context, enumerable may be used to mean computably enumerable. However, these definitions characterize distinct classes since there are uncountably many subsets of Natural numbers that can be enumerated by an arbitrary function with domain ω and only countably many computable functions. A specific example of a set with an enumeration but not a computable enumeration is the complement of the halting set.

Furthermore, this characterization illustrates a place where the ordering of the listing is important. There exists a computable enumeration of the halting set, but not one that lists the elements in an increasing ordering. If there were one, then the halting set would be decidable, which is provably false. In general, being recursively enumerable is a weaker condition than being a decidable set.

See also

External Links

- Manual of the Enumeration, A Text Book on the Sciences of the Enumeration by C. J. Coffman at www.gutenberg.org

References

- Jech, Thomas (2002). Set theory, third millennium edition (revised and expanded). Springer. ISBN 3-540-44085-2.