Divisor (algebraic geometry)

In algebraic geometry, divisors are a generalization of codimension one subvarieties of algebraic varieties; two different generalizations are in common use, Cartier divisors and Weil divisors (named for Pierre Cartier and André Weil). These concepts agree on non-singular varieties.

Contents |

Divisors in a Riemann surface

A Riemann surface is a 1-dimensional complex manifold, so its codimension 1 submanifolds are 0-dimensional. The divisors of a Riemann surface are the elements of the free abelian group of points on the surface.

Equivalently, a divisor is a finite linear combination of points of the surface with integer coefficients. The degree of a divisor is the sum of its coefficients.

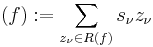

We define the divisor of a meromorphic function f as

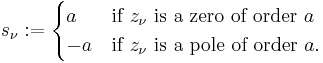

where R(f) is the set of all zeroes and poles of f, and sν is given by

A divisor that is the divisor of a meromorphic function is called principal. It follows from the fact that a meromorphic function has as many poles as zeroes, that the degree of a principal divisor is 0. Since the divisor of a product is the sum of the divisors, the set of principal divisors is a subgroup of the group of divisors. Two divisors that differ by a principal divisor are called linearly equivalent.

We define the divisor of a meromorphic 1-form similarly. Since the space of meromorphic 1-forms is a 1-dimensional vector space over the field of meromorphic functions, any two meromorphic 1-forms yield linearly equivalent divisors. The class of equivalence of these divisors is called the canonical divisor (usually denoted K).

The Riemann–Roch theorem is an important relation between the divisors of a Riemann surface and its topology.

Weil divisor

A Weil divisor is a locally finite linear combination (with integral coefficients) of irreducible subvarieties of codimension one. The set of Weil divisors forms an abelian group under addition. In the classical theory, where locally finite is automatic, the group of Weil divisors on a variety of dimension n is therefore the free abelian group on the (irreducible) subvarieties of dimension (n − 1). For example, a divisor on an algebraic curve is a formal sum of its closed points. An effective Weil divisor is then one in which all the coefficients of the formal sum are non-negative.

Cartier divisor

A Cartier divisor can be represented by an open cover by affine sets  , and a collection of rational functions

, and a collection of rational functions  defined on

defined on  . The functions must be compatible in this sense: on the intersection of two sets in the cover, the quotient of the corresponding rational functions should be regular and invertible. A Cartier divisor is said to be effective if these

. The functions must be compatible in this sense: on the intersection of two sets in the cover, the quotient of the corresponding rational functions should be regular and invertible. A Cartier divisor is said to be effective if these  can be chosen to be regular functions, and in this case the Cartier divisor defines an associated subvariety of codimension 1 by forming the ideal sheaf generated locally by the

can be chosen to be regular functions, and in this case the Cartier divisor defines an associated subvariety of codimension 1 by forming the ideal sheaf generated locally by the  .

.

The notion can be described more conceptually with the function field. For each affine open subset U, define K′(U) to be the total quotient ring of OX(U). Because the affine open subsets form a basis for the topology on X, this defines a presheaf on X. (This is not the same as taking the total quotient ring of OX(U) for arbitrary U, since that does not define a presheaf.[1]) The sheaf KX of rational functions on X is the sheaf associated to the presheaf K′, and the quotient sheaf KX* / OX* is the sheaf of local Cartier divisors.

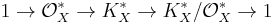

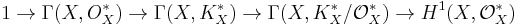

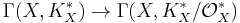

A Cartier divisor is a global section of the quotient sheaf KX*/OX*. We have the exact sequence  , so, applying the global section functor

, so, applying the global section functor  gives the exact sequence

gives the exact sequence  .

.

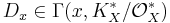

A Cartier divisor is said to be principal if it is in the range of the morphism  , that is, if it is the class of a global rational function.

, that is, if it is the class of a global rational function.

Cartier divisors in non rigid sheaves

Of course the notion of Cartier divisors exists in any sheaf. But if the sheaf is not rigid enough, the notion tends to lose some of its interest. For example in a fine sheaf (e.g. the sheaf of real-valued continuous, or smooth, functions on an open subset of a euclidean space, or locally homeomorphic, or diffeomorphic, to such a set, such as a topological manifold), any local section is a divisor of 0, so that the total quotient sheaves are zero, so that the sheaf contains no non-trivial Cartier divisor.

From Cartier divisors to Weil divisor

There is a natural homomorphism from the group of Cartier divisors to that of Weil divisors, which is an isomorphism for integral separated Noetherian schemes provided that all local rings are unique factorization domains.

In general Cartier behave better than Weil divisors when the variety has singular points.

An example of a surface on which the two concepts differ is a cone, i.e. a singular quadric. At the (unique) singular point, the vertex of the cone, a single line drawn on the cone is a Weil divisor — but is not a Cartier divisor.

The divisor appellation is part of the history of the subject, going back to the Dedekind–Weber work which in effect showed the relevance of Dedekind domains to the case of algebraic curves.[2] In that case the free abelian group on the points of the curve is closely related to the fractional ideal theory.

From Cartier divisors to line bundles

The notion of transition map associates naturally to every Cartier divisor D a line bundle (strictly, invertible sheaf) commonly denoted by OX(D).

The line bundle  associated to the Cartier divisor D is the sub-bundle of the sheaf KX of rational fractions described above whose stalk at

associated to the Cartier divisor D is the sub-bundle of the sheaf KX of rational fractions described above whose stalk at  is given by

is given by  viewed as a line on the stalk at x of

viewed as a line on the stalk at x of  in the stalk at x of

in the stalk at x of  . The subsheaf thus described is tautollogically locally freely monogenous over the structure sheaf

. The subsheaf thus described is tautollogically locally freely monogenous over the structure sheaf  .

.

The application  is a group morphism: the sum of divisors corresponds to the tensor product of line bundles, and isomorphism of bundles corresponds precisely to linear equivalence of Cartier divisors. The group of divisors classes modulo linear equivalence therefore injects in the Picard group The mapping is not always surjective.

is a group morphism: the sum of divisors corresponds to the tensor product of line bundles, and isomorphism of bundles corresponds precisely to linear equivalence of Cartier divisors. The group of divisors classes modulo linear equivalence therefore injects in the Picard group The mapping is not always surjective.

Global sections of line bundles and linear systems

Recall that the local equations of a Cartier divisor  in a variety

in a variety  can be thought of as a the transition maps of a line bundle

can be thought of as a the transition maps of a line bundle  , and linear equivalence as isomorphism of line bundles.

, and linear equivalence as isomorphism of line bundles.

Loosely speaking, a Cartier divisor D is said to be effective if it is the zero locus of a global section of its associated line bundle  . In terms of the definition above, this means that its local equations coincide with the equations of the vanishing locus of a global section.

. In terms of the definition above, this means that its local equations coincide with the equations of the vanishing locus of a global section.

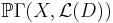

From the divisor linear equivalence/line bundle isormorphism principle, a Cartier divisor is linearly equivalent to an effective divisor if, and only if, its associate line bundle  has non-zero global sections. Two colinear non-zero global sections have the same vanishing locus, and hence the projective space

has non-zero global sections. Two colinear non-zero global sections have the same vanishing locus, and hence the projective space  over k identifies with the set of effective divisors linearly equivalent to

over k identifies with the set of effective divisors linearly equivalent to  .

.

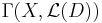

If the space  is noetherian, then

is noetherian, then  is finite dimensional and is called the complete linear system of

is finite dimensional and is called the complete linear system of  . Its subspaces are called linear systems of divisors, and constitute a fundamental tool in algebraic geometry. The Riemann-Roch theorem for algebraic curves is a fundamental identity involving the dimension of complete linear systems in the simple setup of projective curves.

. Its subspaces are called linear systems of divisors, and constitute a fundamental tool in algebraic geometry. The Riemann-Roch theorem for algebraic curves is a fundamental identity involving the dimension of complete linear systems in the simple setup of projective curves.

See also

Notes

- ^ Kleiman, p. 203

- ^ Section VI.6 of Dieudonné (1985).

References

- Dieudonné, Jean (1985), History of algebraic geometry. An outline of the history and development of algebraic geometry (Translated from the French by Judith D. Sally), Wadsworth Mathematics Series, Belmont, CA: Wadsworth International Group, ISBN 0-534-03723-2, MR0780183

- Section II.6 of Hartshorne, Robin (1977), Algebraic Geometry, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 52, New York, Heidelberg, ISBN 0-387-90244-9, MR0463157

- Kleiman, Steven (1979), "Misconceptions about KX", L'Enseignment Mathématique 25: 203–206, doi:10.5169/seals-50379