Division (digital)

Several algorithms exist to perform division in digital designs. These algorithms fall into two main categories: slow division and fast division. Slow division algorithms produce one digit of the final quotient per iteration. Examples of slow division include restoring, non-performing restoring, non-restoring, and SRT division. Fast division methods start with a close approximation to the final quotient and produce twice as many digits of the final quotient on each iteration. Newton-Raphson and Goldschmidt fall into this category.

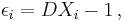

The following division methods are all based on the form  where

where

- Q = Quotient

- N = Numerator (dividend)

- D = Denominator (divisor).

Contents |

Slow division methods

Slow division methods are all based on a standard recurrence equation:

where:

- Pj = the partial remainder of the division

- R = the radix

- q n-( j + 1) = the digit of the quotient in position n-(j+1), where the digit positions are numbered from least-significant 0 to most significant n-1

- n = number of digits in the quotient

- D = the denominator.

Restoring division

Restoring division operates on fixed-point fractional numbers and depends on the following assumptions:

- D < N

- 0 < N,D < 1.

The quotient digits q are formed from the digit set {0,1}.

The basic algorithm for binary (radix 2) restoring division is:

P := N

D := D << n * P and D need twice the word width of N and Q

for i = n-1..0 do * for example 31..0 for 32 bits

P := 2P - D * trial subtraction from shifted value

if P >= 0 then

q(i) := 1 * result-bit 1

else

q(i) := 0 * result-bit 0

P := P + D * new partial remainder is (restored) shifted value

end

end

where N=Numerator, D=Denominator, n=#bits, P=Partial remainder, q(i)=bit #i of quotient

The above restoring division algorithm can avoid the restoring step by saving the shifted value 2P before the subtraction in an additional register T (i.e., T=P<<1) and copying register T to P when the result of the subtraction 2P - D is negative.

Non-performing restoring division is similar to restoring division except that the value of 2*P[i] is saved, so D does not need to be added back in for the case of TP[i] ≤ 0.

Non-restoring division

Non-restoring division uses the digit set {−1,1} for the quotient digits instead of {0,1}. The basic algorithm for binary (radix 2) non-restoring division is:

P[0] := N

i := 0

while i < n do

if P[i] >= 0 then

q[n-(i+1)] := 1

P[i+1] := 2*P[i] - D

else

q[n-(i+1)] := -1

P[i+1] := 2*P[i] + D

end if

i := i + 1

end while

Following this algorithm, the quotient is in a non-standard form consisting of digits of −1 and +1. This form needs to be converted to binary to form the final quotient. Example:

| Convert the following quotient to the digit set {0,1}: |  |

| Steps: | |

| 1. Mask the negative term: |  |

| 2. Form the two's complement of N: |  |

| 3. Form the positive term: |  |

4. Sum  and and  : : |

|

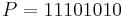

SRT division

Named for its creators (Sweeney, Robertson, and Tocher), SRT division is a popular method for division in many microprocessor implementations. SRT division is similar to non-restoring division, but it uses a lookup table based on the dividend and the divisor to determine each quotient digit. The Intel Pentium processor's infamous floating-point division bug was caused by an incorrectly coded lookup table. Five entries that were believed to be theoretically unreachable had been omitted from more than one thousand table entries.[1]

Fast division methods

Newton–Raphson division

Newton–Raphson uses Newton's method to find the reciprocal of  , and multiply that reciprocal by

, and multiply that reciprocal by  to find the final quotient

to find the final quotient  .

.

The steps of Newton–Raphson are:

- Calculate an estimate for the reciprocal of the divisor (

):

):  .

. - Compute successively more accurate estimates of the reciprocal:

- Compute the quotient by multiplying the dividend by the reciprocal of the divisor:

.

.

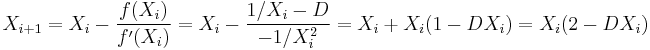

In order to apply Newton's method to find the reciprocal of  , it is necessary to find a function

, it is necessary to find a function  which has a zero at

which has a zero at  . The obvious such function is

. The obvious such function is  , but the Newton–Raphson iteration for this is unhelpful since it cannot be computed without already knowing the reciprocal of

, but the Newton–Raphson iteration for this is unhelpful since it cannot be computed without already knowing the reciprocal of  . A function which does work is

. A function which does work is  , for which the Newton–Raphson iteration gives

, for which the Newton–Raphson iteration gives

which can be calculated from  using only multiplication and subtraction, or using two fused multiply–adds.

using only multiplication and subtraction, or using two fused multiply–adds.

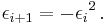

If the error is defined as  then

then

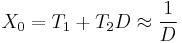

Apply a bit-shift to the divisor D to scale it so that 0.5 ≤ D ≤ 1 . The same bit-shift should be applied to the numerator N so that the quotient does not change. Then one could use a linear approximation in the form

to initialize Newton–Raphson. To minimize the maximum of the absolute value of the error of this approximation on interval ![[0.5,1]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/c0b44a4b6b69860fae9e937e945bf5b0.png) one should use

one should use

Using this approximation, the error of the initial value is less than

Since for this method the convergence is exactly quadratic, it follows that

steps is enough to calculate the value up to  binary places.

binary places.

Goldschmidt division

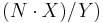

Goldschmidt (after Robert Elliott Goldschmidt)[2] division uses an iterative process to repeatedly multiply both the dividend and divisor by a common factor Fi to converge the divisor, D, to 1 as the dividend, N, converges to the quotient Q:

The steps for Goldschmidt division are:

- Generate an estimate for the multiplication factor Fi .

- Multiply the dividend and divisor by Fi .

- If the divisor is sufficiently close to 1, return the dividend, otherwise, loop to step 1.

Assuming N/D has been scaled so that 0 < D < 1, each Fi is based on D:

Multiplying the dividend and divisor by the factor yields:

.

.

After a sufficient number of iterations k:

The Goldschmidt method is used in AMD Athlon CPUs and later models.[3][4]

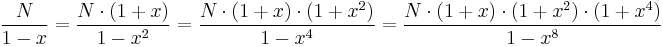

Binomial theorem

The Goldschmidt method can be used with factors that allow simplifications by the Binomial theorem. Assuming N/D has been scaled by a power of two such that ![D\in(\tfrac{1}{2},1]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/c91b853d5c25f0bd322cdb0c7008c7d5.png) . We choose

. We choose  and

and  . This yields

. This yields  . Since

. Since  after

after  steps we can round

steps we can round  to 1 with a relative error of at most

to 1 with a relative error of at most  and thus we obtain

and thus we obtain  binary digits precision. This algorithm is referred to as the IBM method in.[5]

binary digits precision. This algorithm is referred to as the IBM method in.[5]

Large integer methods

Methods designed for hardware implementation generally do not scale to integers with thousands or millions of decimal digits; these frequently occur, for example, in modular reductions in cryptography. For these large integers, more efficient division algorithms transform the problem to use a small number of multiplications, which can then be done using an asymptotically efficient multiplication algorithm such as Toom–Cook multiplication or the Schönhage–Strassen algorithm. Examples include reduction to multiplication by Newton's method as described above[6] as well as the slightly faster Barrett reduction algorithm.[7] Newton's method's is particularly efficient in scenarios where one must divide by the same divisor many times, since after the initial Newton inversion only one (truncated) multiplication is needed for each division.

Division by a constant

Division by a constant is equivalent to multiplication by its reciprocal. Since the denominator  is constant, so is its reciprocal

is constant, so is its reciprocal  . Thus it is possible to compute the value of

. Thus it is possible to compute the value of  once at compile time, and at run time perform the multiplication

once at compile time, and at run time perform the multiplication  rather than the division

rather than the division

When doing floating point arithmetic the use of  presents no problem. But when doing integer arithmetic it is problematic, as

presents no problem. But when doing integer arithmetic it is problematic, as  will always evaluate to zero (assuming D > 1), so it is necessary to do some manipulations to make it work.

will always evaluate to zero (assuming D > 1), so it is necessary to do some manipulations to make it work.

Note that it is not necessary to use  . Any value

. Any value  will work as long as it reduces to

will work as long as it reduces to  . For example, for division by 3 the reciprocal is 1/3. So the division could be changed to multiplying by 1/3, but it could also be a multiplication by 2/6, or 3/9, or 194/582. So the desired operation of

. For example, for division by 3 the reciprocal is 1/3. So the division could be changed to multiplying by 1/3, but it could also be a multiplication by 2/6, or 3/9, or 194/582. So the desired operation of  can be changed to

can be changed to  , where

, where  equals

equals  . Although the quotient

. Although the quotient  would still evaluate to zero, it is possible to do another adjustment and reorder the operations to produce

would still evaluate to zero, it is possible to do another adjustment and reorder the operations to produce  .

.

This form appears to be less efficient because it involves both a multiplication and a division, but if Y is a power of two, then the division can be replaced by a fast bit shift. So the effect is to replace a division by a multiply and a shift.

There's one final obstacle to overcome - in general it is not possible to find values X and Y such that Y is a power of 2 and  . But it turns out that it is not necessary for

. But it turns out that it is not necessary for  to be exactly equal to

to be exactly equal to  in order to get the correct final result. It is sufficient to find values for X and Y such that

in order to get the correct final result. It is sufficient to find values for X and Y such that  is "close enough" to

is "close enough" to  . Note that the shift operation loses information by throwing away bits. It is always possible to find values of X and Y (with Y being a power of 2) such that the error introduced by the fact that

. Note that the shift operation loses information by throwing away bits. It is always possible to find values of X and Y (with Y being a power of 2) such that the error introduced by the fact that  is only approximately equal to

is only approximately equal to  is in the bits that are discarded. For further details please see the reference.[8]

is in the bits that are discarded. For further details please see the reference.[8]

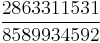

As a concrete example - for 32 bit unsigned integers, division by 3 can be replaced with a multiply by  . The denominator in this case is equal to

. The denominator in this case is equal to  .

.

In some cases, division by a constant can be accomplished in even less time by converting the "multiply by a constant" into a series of shifts and adds or subtracts.[9]

Rounding error

Round-off error can be introduced by division operations due to limited precision.

See also

References

- ^ Intel Corporation, 1994, Retrieved 2011-10-19,"Statistical Analysis of Floating Point Flaw"

- ^ Robert E. Goldschmidt, Applications of Division by Convergence, MSc dissertation, M.I.T., 1964

- ^ Stuart F. Oberman, "Floating Point Division and Square Root Algorithms and Implementation in the AMD-K7 Microprocessor", in Proc. IEEE Symposium on Computer Arithmetic, pp. 106–115, 1999

- ^ Peter Soderquist and Miriam Leeser, "Division and Square Root: Choosing the Right Implementation", IEEE Micro, Vol.17 No.4, pp.56–66, July/August 1997

- ^ Paul Molitor, "Entwurf digitaler Systeme mit VHDL"

- ^ Hasselström, Karl (2003). Fast Division of Large Integers: A Comparison of Algorithms (Master's in Computer Science thesis). Royal Institute of Technology. http://www.treskal.com/kalle/exjobb/original-report.pdf. Retrieved 2011-03-23.

- ^ Paul Barrett (1987). "Implementing the Rivest Shamir and Adleman public key encryption algorithm on a standard digital signal processor". Proceedings on Advances in cryptology---CRYPTO '86. London, UK: Springer-Verlag. pp. 311–323. ISBN 0-387-18047-8. http://portal.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=36688.

- ^ Division by Invariant Integers using Multiplication Torbjörn Granlund and Peter L. Montgomery. ACM SIGPLAN Notices Vol 29 Issue 6 (June 1994) 61 - 72

- ^ Massmind: "Binary Division by a Constant"

External links

- Computer Arithmetic Algorithms JavaScript Simulator - contains simulators for many different division algorithms