Discounting

Discounting is a financial mechanism in which a debtor obtains the right to delay payments to a creditor, for a defined period of time, in exchange for a charge or fee.[1] Essentially, the party that owes money in the present purchases the right to delay the payment until some future date.[2] The discount, or charge, is simply the difference between the original amount owed in the present and the amount that has to be paid in the future to settle the debt.[1]

The discount is usually associated with a discount rate, which is also called the discount yield.[1][1][2][3] The discount yield is simply the proportional share of the initial amount owed (initial liability) that must be paid to delay payment for 1 year.

Discount Yield = "Charge" to Delay Payment for 1 year / Debt Liability

It is also the rate at which the amount owed must rise to delay payment for 1 year.

Since a person can earn a return on money invested over some period of time, most economic and financial models assume the "Discount Yield" is the same as the Rate of Return the person could receive by investing this money elsewhere (in assets of similar risk) over the given period of time covered by the delay in payment.[1][2] The Concept is associated with the Opportunity Cost of not having use of the money for the period of time covered by the delay in payment. The relationship between the "Discount Yield" and the Rate of Return on other financial assets is usually discussed in such economic and financial theories involving the inter-relation between various Market Prices, and the achievement of Pareto Optimality through the operations in the Capitalistic Price Mechanism,[2] as well as in the discussion of the "Efficient (Financial) Market Hypothesis".[1][2][4] The person delaying the payment of the current Liability is essentially compensating the person to whom he/she owes money for the lost revenue that could be earned from an investment during the time period covered by the delay in payment.[1] Accordingly, it is the relevant "Discount Yield" that determines the "Discount", and not the other way around.

As indicated, the Rate of Return is usually calculated in accordance to an annual return on investment. Since an investor earns a return on the original principal amount of the investment as well as on any prior period Investment income, investment earnings are "compounded" as time advances.[1][2] Therefore, considering the fact that the "Discount" must match the benefits obtained from a similar Investment Asset, the "Discount Yield" must be used within the same compounding mechanism to negotiate an increase in the size of the "Discount" whenever the time period the payment is delayed or extended.[2][4] The “Discount Rate” is the rate at which the “Discount” must grow as the delay in payment is extended.[5] This fact is directly tied into the "Time Value of Money" and its calculations.[1]

The "Time Value of Money" indicates there is a difference between the "Future Value" of a payment and the "Present Value" of the same payment. The Rate of Return on investment should be the dominant factor in evaluating the market's assessment of the difference between the "Future Value" and the "Present Value" of a payment; and it is the Market's assessment that counts the most.[4] Therefore, the "Discount Yield", which is predetermined by a related Return on Investment that is found in the financial markets, is what is used within the "Time Value of Money" calculations to determine the "Discount" required to delay payment of a financial liability for a given period of time.

BASIC CALCULATION

If we consider the value of the original payment presently due to be $P, and the debtor wants to delay the payment for t years, then an r% Market Rate of Return on a similar Investment Assets means the "Future Value" of $P is $P * (1 + r%)t ,[2][5] and the "Discount" would be calculated as

Discount = $P * (1+r%)t - $P [2]

where r% is also the "Discount Yield".

If $F is a payment that will be made t years in the future, then the "Present Value" of this Payment, also called the "Discounted Value" of the payment, is

$P = $F / (1+r%)t [2]

Contents |

Example

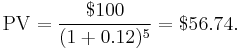

To calculate the present value of a single cash flow, it is divided by one plus the interest rate for each period of time that will pass. This is expressed mathematically as raising the divisor to the power of the number of units of time.

Consider the task to find the present value PV of $100 that will be received in five years. Or equivalently, which amount of money today will grow to $100 in five years when subject to a constant discount rate?

Assuming a 12% per year interest rate it follows

Discount rate

The discount rate which is used in financial calculations is usually chosen to be equal to the Cost of Capital. The Cost of Capital, in a financial market equilibrium, will be the same as the Market Rate of Return on the financial asset mixture the firm uses to finance capital investment. Some adjustment may be made to the discount rate to take account of risks associated with uncertain cash flows, with other developments.

The discount rates typically applied to different types of companies show significant differences:

- Startups seeking money: 50 – 100 %

- Early Startups: 40 – 60 %

- Late Startups: 30 – 50%

- Mature Companies: 10 – 25%

Reason for high discount rates for startups:

- Reduced marketability of ownerships because stocks are not traded publicly.

- Limited number of investors willing to invest.

- Startups face high risks.

- Over optimistic forecasts by enthusiastic founders.

One method that looks into a correct discount rate is the capital asset pricing model. This model takes in account three variables that make up the discount rate:

1. Risk Free Rate: The percentage of return generated by investing in risk free securities such as government bonds.

2. Beta: The measurement of how a company’s stock price reacts to a change in the market. A beta higher than 1 means that a change in share price is exaggerated compared to the rest of shares in the same market. A beta less than 1 means that the share is stable and not very responsive to changes in the market. Less than 0 means that a share is moving in the opposite of the market change.

3. Equity Market Risk Premium: The return on investment that investors require above the risk free rate.

Discount rate= risk free rate + beta*(equity market risk premium)

Discount factor

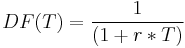

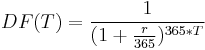

The discount factor, DF(T), is the factor by which a future cash flow must be multiplied in order to obtain the present value. For a zero-rate (also called spot rate)  , taken from a yield curve, and a time to cashflow

, taken from a yield curve, and a time to cashflow  (in years), the discount factor is:

(in years), the discount factor is:

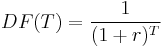

In the case where the only discount rate you have is not a zero-rate (neither taken from a zero-coupon bond nor converted from a swap rate to a zero-rate through bootstrapping) but an annually-compounded rate (for example if your benchmark is a US Treasury bond with annual coupons and you only have its yield to maturity, you would use an annually-compounded discount factor:

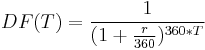

However, when operating in a bank, where the amount the bank can lend (and therefore get interest) is linked to the value of its assets (including accrued interest), traders usually use daily compounding to discount cashflows. Indeed, even if the interest of the bonds it holds (for example) is paid semi-annually, the value of its book of bond will increase daily, thanks to accrued interest being accounted for, and therefore the bank will be able to re-invest these daily accrued interest (by lending additional money or buying more financial products). In that case, the discount factor is then (if the usual money market day count convention for the currency is ACT/360, in case of currencies such as USD, EUR, JPY), with  the zero-rate and

the zero-rate and  the time to cashflow in years:

the time to cashflow in years:

or, in case the market convention for the currency being discounted is ACT/365 (AUD, CAD, GBP):

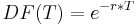

Sometimes, for manual calculation, the continuously-compounded hypothesis is a close-enough approximation of the daily-compounding hypothesis, and makes calculation easier (even though it does not have any real application as no financial instrument is continuously compounded). In that case, the discount factor is:

Other discounts

For discounts in marketing, see discounts and allowances, sales promotion, and pricing. The article on Discounted Cash Flow provides a nice example about discounting and risks in real estate investments.

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i

J. Downes, J.E. Goodman, "Dictionary of Finance & Investment Terms", Baron's Financial Guides, 2003.See "Time Value", "Discount", "Discount Yield", "Compound Interest", "Efficient Market", "Market Value", "Opportunity Cost":

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j

See "Discount", "Compound Interest", "Efficient Markets Hypothesis", "Efficient Resource Allocation", "Pareto-Optimality", "Price" & "Price Mechanism", "Efficient Market":

John Black, "Oxford Dictionary of Economics", Oxford University Press, 2002.

- ^ Here, the discount rate is different from the Discount Rate the nation's Central Bank charges financial institutions.

- ^ a b c Competition from other firms who offer other Financial Assets that promise the Market Rate of Return forces the person who is asking for a delay in payment to offer a "Discount Yield" that is the same as the Market Rate of Return.

- ^ a b Alpha C Chiang, "Fundamental Methods of Mathematical Economics, Third Edition", McGraw Hill Book Company, 1984.