Classification of discontinuities

Continuous functions are of utmost importance in mathematics and applications. However, not all functions are continuous. If a function is not continuous at a point in its domain, one says that it has a discontinuity there. The set of all points of discontinuity of a function may be a discrete set, a dense set, or even the entire domain of the function.

This article describes the classification of discontinuities in the simplest case of functions of a single real variable taking real values.

Contents |

Classification of discontinuities

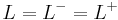

Consider a real valued function ƒ of a real variable x, defined in a neighborhood of the point x0 in which ƒ is discontinuous. Then three situations may be distinguished:

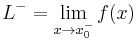

- The one-sided limit from the negative direction

exist, are finite, and are equal to

exist, are finite, and are equal to  . Then, if ƒ(x0) is not equal to

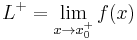

. Then, if ƒ(x0) is not equal to  , x0 is called a removable discontinuity. This discontinuity can be 'removed to make ƒ continuous at x0', or more precisely, the function

, x0 is called a removable discontinuity. This discontinuity can be 'removed to make ƒ continuous at x0', or more precisely, the function

- The limits

and

and  exist and are finite, but not equal. Then, x0 is called a jump discontinuity or step discontinuity. For this type of discontinuity, the function ƒ may have any value in x0.

exist and are finite, but not equal. Then, x0 is called a jump discontinuity or step discontinuity. For this type of discontinuity, the function ƒ may have any value in x0. - One or both of the limits

and

and  does not exist or is infinite. Then, x0 is called an essential discontinuity, or infinite discontinuity. (This is distinct from the term essential singularity which is often used when studying functions of complex variables.)

does not exist or is infinite. Then, x0 is called an essential discontinuity, or infinite discontinuity. (This is distinct from the term essential singularity which is often used when studying functions of complex variables.)

The term removable discontinuity is sometimes incorrectly used for cases in which the limits in both directions exist and are equal, while the function is undefined at the point  [1] This use is improper because continuity and discontinuity of a function are concepts defined only for points in the function's domain. Such a point not in the domain, is properly named a removable singularity.

[1] This use is improper because continuity and discontinuity of a function are concepts defined only for points in the function's domain. Such a point not in the domain, is properly named a removable singularity.

The oscillation of a function at a point quantifies these discontinuities as follows:

- in a removable discontinuity, the distance that the value of the function is off by is the oscillation;

- in a jump discontinuity, the size of the jump is the oscillation (assuming that the value at the point lies between these limits from the two sides);

- in an essential discontinuity, oscillation measures the failure of a limit to exist.

Examples

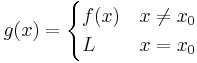

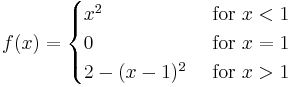

1. Consider the function

Then, the point  is a removable discontinuity.

is a removable discontinuity.

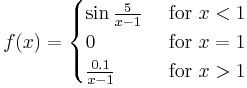

2. Consider the function

Then, the point  is a jump discontinuity.

is a jump discontinuity.

3. Consider the function

Then, the point  is an essential discontinuity (sometimes called infinite discontinuity). For it to be an essential discontinuity, it would have sufficed that only one of the two one-sided limits did not exist or were infinite. However, given this example the discontinuity is also an essential discontinuity for the extension of the function into complex variables.

is an essential discontinuity (sometimes called infinite discontinuity). For it to be an essential discontinuity, it would have sufficed that only one of the two one-sided limits did not exist or were infinite. However, given this example the discontinuity is also an essential discontinuity for the extension of the function into complex variables.

The set of discontinuities of a function

The set of points at which a function is continuous is always a Gδ set. The set of discontinuities is an Fσ set.

The set of discontinuities of a monotonic function is at most countable. This is Froda's theorem.

Thomae's function is discontinuous at every rational point, but continuous at every irrational point.

The indicator function of the rationals, also known as the Dirichlet function, is discontinuous everywhere.

See also

Notes

References

- Malik, S. C.; Arora, Savita (1992). Mathematical analysis, 2nd ed. New York: Wiley. ISBN 0470218584.

External links

- Discontinuous on PlanetMath

- "Discontinuity" by Ed Pegg, Jr., The Wolfram Demonstrations Project, 2007.

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Discontinuity" from MathWorld.

- "Discontinuity point" by L. D. Kudryavtsev, Encyclopaedia of Mathematics.