Crystalline cohomology

In mathematics, crystalline cohomology is a Weil cohomology theory for schemes introduced by Alexander Grothendieck (1966, 1968) and developed by Pierre Berthelot (1974). Its values are modules over rings of Witt vectors over the base field.

Crystalline cohomology is partly inspired by the p-adic proof in Dwork (1960) of part of the Weil conjectures and is closely related to the (algebraic) de Rham cohomology introduced by Grothendieck (1963). Roughly speaking, crystalline cohomology of a variety X in characteristic p is the de Rham cohomology of a smooth lift of X to characteristic 0, while de Rham cohomology of X is the crystalline cohomology reduced mod p (after taking into account higher Tors).

The idea of crystalline cohomology, roughly, is to replace the Zariski open sets of a scheme by infinitesimal thickenings of Zariski open sets with divided power structures. The motivation for this is that it can then be calculated by taking a local lifting of a scheme from characteristic p to characteristic 0 and employing an appropriate version of algebraic de Rham cohomology.

Crystalline cohomology only works well for smooth proper schemes. Rigid cohomology extends it to more general schemes.

Contents |

Applications

For schemes in characteristic p, crystalline cohomology theory can handle questions about p-torsion in cohomology groups better than p-adic étale cohomology. This makes it a natural backdrop for much of the work on p-adic L-functions.

Crystalline cohomology, from the point of view of number theory, fills a gap in the l-adic cohomology information, which occurs exactly where there are 'equal characteristic primes'. Traditionally the preserve of ramification theory, crystalline cohomology converts this situation into Dieudonné module theory, giving an important handle on arithmetic problems. Conjectures with wide scope on making this into formal statements were enunciated by Jean-Marc Fontaine, the resolution of which is called p-adic Hodge theory.

de Rham cohomology

De Rham cohomology solves the problem of finding an algebraic definition of the cohomology groups (singular cohomology)

- Hi(X,C)

for X a smooth complex variety. These groups are the cohomology of the complex of smooth differential forms on X (with complex number coefficients), as these form a resolution of the constant sheaf C.

The algebraic de Rham cohomology is defined to be the hypercohomology of the complex of algebraic forms (Kähler differentials) on X. The smooth i-forms form an acyclic sheaf, so the hypercohomology of the complex of smooth forms is the same as its cohomology, and the same is true for algebraic sheaves of i-forms over affine varieties, but algebraic sheaves of i-forms over non-affine varieties can have non-vanishing higher cohomology groups, so the hypercohomology can differ from the cohomology of the complex.

For smooth complex varieties Grothendieck (1963) showed that the algebraic de Rham cohomology is isomorphic to the usual smooth de Rham cohomology and therefore (by de Rham's theorem) to the cohomology with complex coefficients. This definition of algebraic de Rham cohomology is available for algebraic varieties over any field k.

Coefficients

If X is a variety over an algebraically closed field of characteristic p > 0, then the l-adic cohomology groups for l any prime number other than p give satisfactory cohomology groups of X, with coefficients in the ring Zl of l-adic integers. It is not possible in general to find similar cohomology groups with coefficients in the p-adic numbers (or the rationals, or the integers).

The classic reason (due to Serre) is that if X is a supersingular elliptic curve, then its ring of endomorphisms generates a quaternion algebra over Q that is non-split at p and infinity. If X has a cohomology group over the p-adic integers with the expected dimension 2, the ring of endomorphisms would have a 2-dimensional representation; and this is not possible as it is non-split at p. (A quite subtle point is that if X is a supersingular elliptic curve over the prime field, with p elements, then its crystalline cohomology is a free rank 2 module over the p-adic integers. The argument given does not apply in this case, because some of the endomorphisms of supersingular elliptic curves are only defined over a quadratic extension of the field of order p.)

Grothendieck's crystalline cohomology theory gets around this obstruction because it takes values in the ring of Witt vectors over the ground field. So if the ground field is the algebraic closure of the field of order p, its values are modules over the p-adic completion of the maximal unramified extension of the p-adic integers, a much larger ring containing n-th roots of unity for all n not divisible by p, rather than over the p-adic integers.

Motivation

One idea for defining a Weil cohomology theory of a variety X over a field k of characteristic p is to 'lift' it to a variety X* over the ring of Witt vectors of k (that gives back X on reduction mod p), then take the de Rham cohomology of this lift. The problem is that it is not at all obvious that this cohomology is independent of the choice of lifting.

The idea of crystalline cohomology in characteristic 0 is to find a direct definition of a cohomology theory as the cohomology of constant sheaves on a suitable site

- Inf(X)

over X, called the infinitesimal site and then show it is the same as the de Rham cohomology of any lift.

The site Inf(X) is a category whose objects can be thought of as some sort of generalization of the conventional open sets of X. In characteristic 0 its objects are infinitesimal thickenings U→T of Zariski open subsets U of X. This means that U is the closed subscheme of a scheme T defined by a nilpotent sheaf of ideals on T; for example, Spec(k)→ Spec(k[x]/(x2)).

Grothendieck showed that for smooth schemes X over C, the cohomology of the sheaf OX on Inf(X) is the same as the usual (smooth or algebraic) de Rham cohomology.

Crystalline cohomology

In characteristic p the most obvious analogue of the crystalline site defined above in characteristic 0 does not work. The reason is roughly that in order to prove exactness of the de Rham complex, one needs some sort of Poincaré lemma, whose proof in turn uses integration, and integration requires various divided powers, which exist in characteristic 0 but not always in characteristic p. Grothendieck solved this problem by defining objects of the crystalline site of X to be roughly infinitesimal thickenings of Zariski open subsets of X, together with a divided power structure giving the needed divided powers.

We will work over the ring Wn = W/pnW of Witt vectors of length n over a perfect field k of characteristic p>0. For example, k could be the finite field of order p, and Wn is then the ring Z/pnZ. (More generally one can work over a base scheme S which has a fixed sheaf of ideals I with a divided power structure.) If X is a scheme over k, then the crystalline site of X relative to Wn, denoted Cris(X/Wn), has as its objects pairs U→T consisting of a closed immersion of a Zariski open subset U of X into some Wn-scheme T defined by a sheaf of ideals J, together with a divided power structure on J compatible with the one on Wn.

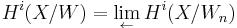

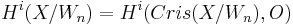

Crystalline cohomology of a scheme X over k is defined to be the inverse limit

where

is the cohomology of the crystalline site of X/Wn with values in the sheaf of rings O = OX/Wn.

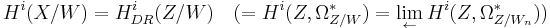

A key point of the theory is that the crystalline cohomology of a smooth scheme X over k can often be calculated in terms of the algebraic de Rham cohomology of a proper and smooth lifting of X to a scheme Z over W. There is a canonical isomorphism

of the crystalline cohomology of X with the de Rham cohomology of Z over the formal scheme of W (an inverse limit of the hypercohomology of the complexes of differential forms). Conversely the de Rham cohomology of X can be recovered as the reduction mod p of its crystalline cohomology (after taking higher Tors into account).

Crystals

If X is a scheme over S then the sheaf OX/S is defined by OX/S(T) = coordinate ring of T, where we write T as an abbreviation for an object U→T of Cris(X/S).

A crystal on the site Cris(X/S) is a sheaf F of OX/S modules that is rigid in the following sense:

- for any map f between objects T, T′ of Cris(X/S), the natural map from f*F(T) to F(T′) is an isomorphism.

This is similar to the definition of a quasicoherent sheaf of modules in the Zariski topology.

An example of a crystal is the sheaf OX/S.

The term crystal attached to the theory, explained in Grothendieck's letter to Tate (1966), was a metaphor inspired by certain properties of algebraic differential equations. These had played a role in p-adic cohomology theories (precursors of the crystalline theory, introduced in various forms by Dwork, Monsky, Washnitzer, Lubkin and Katz) particularly in Dwork's work. Such differential equations can be formulated easily enough by means of the algebraic Koszul connections, but in the p-adic theory the analogue of analytic continuation is more mysterious (since p-adic discs tend to be disjoint rather than overlap). By decree, a crystal would have the 'rigidity' and the 'propagation' notable in the case of the analytic continuation of complex analytic functions. (Cf. also the rigid analytic spaces introduced by Tate, in the 1960s, when these matters were actively being debated.)

See also

References

- Berthelot, Pierre (1974), Cohomologie cristalline des schémas de caractéristique p>0, Lecture Notes in Mathematics, Vol. 407, 407, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, doi:10.1007/BFb0068636, ISBN 978-3-540-06852-5, MR0384804

- Berthelot, Pierre; Ogus, Arthur (1978), Notes on crystalline cohomology, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-08218-9, MR0491705

- Chambert-Loir, Antoine (1998), "Cohomologie cristalline: un survol", Expositiones Mathematicae. International Journal 16 (4): 333–382, ISSN 0723-0869, MR1654786, http://perso.univ-rennes1.fr/antoine.chambert-loir/publications

- Dwork, Bernard (1960), "On the rationality of the zeta function of an algebraic variety", American Journal of Mathematics (The Johns Hopkins University Press) 82 (3): 631–648, doi:10.2307/2372974, ISSN 0002-9327, JSTOR 2372974, MR0140494

- Grothendieck, Alexander (1966), "On the de Rham cohomology of algebraic varieties", Institut des Hautes Études Scientifiques. Publications Mathématiques 29 (29): 95–103, doi:10.1007/BF02684807, ISSN 0073-8301, MR0199194, http://www.numdam.org/item?id=PMIHES_1966__29__95_0 (letter to Atiyah, Oct. 14 1963)

- Grothendieck, A. (1966), Letter to J. Tate, http://www.math.jussieu.fr/~leila/grothendieckcircle/crystals.pdf.

- Grothendieck, Alexander (1968), "Crystals and the de Rham cohomology of schemes", in Giraud, Jean; Grothendieck, Alexander; Kleiman, Steven L. et al., Dix Exposés sur la Cohomologie des Schémas, Advanced studies in pure mathematics, 3, Amsterdam: North-Holland, pp. 306–358, MR0269663, http://www.math.jussieu.fr/~leila/grothendieckcircle/DixExp.pdf

- Illusie, Luc (1975), "Report on crystalline cohomology", Algebraic geometry, Proc. Sympos. Pure Math., 29, Providence, R.I.: Amer. Math. Soc., pp. 459–478, MR0393034

- Illusie, Luc (1976), "Cohomologie cristalline (d'après P. Berthelot)", Séminaire Bourbaki (1974/1975: Exposés Nos. 453-470), Exp. No. 456, Lecture Notes in Math., 514, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, pp. 53–60, MR0444668, http://www.numdam.org/numdam-bin/fitem?id=SB_1974-1975__17__53_0

- Illusie, Luc (1994), "Crystalline cohomology", Motives (Seattle, WA, 1991), Proc. Sympos. Pure Math., 55, Providence, RI: Amer. Math. Soc., pp. 43–70, MR1265522

- Kedlaya, Kiran S. (2009), "p-adic cohomology", in Abramovich, Dan; Bertram, A.; Katzarkov, L. et al., Algebraic geometry---Seattle 2005. Part 2, Proc. Sympos. Pure Math., 80, Providence, R.I.: Amer. Math. Soc., pp. 667–684, arXiv:math/0601507, ISBN 978-0-8218-4703-9, MRarXiv:0601507 2483951[[arXiv]]:[[arXiv:0601507|0601507]]