Corrosion

|

Buckling · Corrosion · Creep · Fatigue · |

Corrosion is the disintegration of an engineered material into its constituent atoms due to chemical reactions with its surroundings. In the most common use of the word, this means electrochemical oxidation of metals in reaction with an oxidant such as oxygen. Formation of an oxide of iron due to oxidation of the iron atoms in solid solution is a well-known example of electrochemical corrosion, commonly known as rusting. This type of damage typically produces oxide(s) and/or salt(s) of the original metal. Corrosion can also occur in materials other than metals, such as ceramics or polymers, although in this context, the term degradation is more common..

In other words, corrosion is the wearing away of metals due to a chemical reaction.

Many structural alloys corrode merely from exposure to moisture in the air, but the process can be strongly affected by exposure to certain substances (see below). Corrosion can be concentrated locally to form a pit or crack, or it can extend across a wide area more or less uniformly corroding the surface. Because corrosion is a diffusion controlled process, it occurs on exposed surfaces. As a result, methods to reduce the activity of the exposed surface, such as passivation and chromate-conversion, can increase a material's corrosion resistance. However, some corrosion mechanisms are less visible and less predictable.

Galvanic corrosion

Galvanic corrosion occurs when two different metals and/or alloys have physical or electrical contact with each other and are immersed in a common electrolyte. In a galvanic couple, the more active metal (the anode) corrodes at an accelerated rate and the more noble metal (the cathode) corrodes at a retarded (؟) rate. When immersed separately, each metal corrodes at its own rate. What type of metal(s) to use is readily determined by following the galvanic series. For example, zinc is often used as a sacrificial anode for steel structures. Galvanic corrosion is of major interest to the marine industry and also anywhere water (via impurities such as salt) contacts pipes or metal structures.

In this photo, a 5-mm thick aluminum alloy plate is physically (and hence, electrically) connected to a 10-mm thick mild steel structural support. Galvanic corrosion occurred on the aluminium plate along the joint with the mild steel. Perforation of aluminum plate occurred within 2 years due to the large acceleration factor in galvanic corrosion.[1]

Factors such as relative size of anode, types of metal, and operating conditions (temperature, humidity, salinity, etc.) affect galvanic corrosion. The surface area ratio of the anode and cathode directly affects the corrosion rates of the materials. Galvanic corrosion is often utilized in sacrificial anodes.

Galvanic series

In a given environment (one standard medium is aerated, room-temperature seawater), one metal will be either more noble or more active than the next, based on how strongly its ions are bound to the surface. Two metals in electrical contact share the same electrons, so that the "tug-of-war" at each surface is analogous to competition for free electrons between the two materials. Using the electrolyte as a host for the flow of ions in the same direction; the noble metal will take electrons from the active one. The resulting mass flow or electrical current can be measured to establish a hierarchy of materials in the medium of interest. This hierarchy is called a galvanic series, and can be a very useful in predicting and understanding corrosion.

Corrosion removal

Often it is possible to chemically remove the products of corrosion to give a clean surface, but one that may exhibit artifacts of corrosion such as pitting. For example phosphoric acid in the form of naval jelly is often applied to ferrous tools or surfaces to remove rust.

Corrosion removal should not be confused with Electropolishing which removes some layers of the underlying metal to make a smooth surface. For example phosphoric acid (again) may be used to electropolish copper but it does this by removing copper, not the products of copper corrosion.

Resistance to corrosion

Some metals are more intrinsically resistant to corrosion than others, either due to the fundamental nature of the electrochemical processes involved or due to the details of how reaction products form. For some examples, see galvanic series. If a more susceptible material is used, many techniques can be applied during an item's manufacture and use to protect its materials from damage.

Intrinsic chemistry

The materials most resistant to corrosion are those for which corrosion is thermodynamically unfavorable. Any corrosion products of gold or platinum tend to decompose spontaneously into pure metal, which is why these elements can be found in metallic form on Earth, and is a large part of their intrinsic value. More common "base" metals can only be protected by more temporary means.

Some metals have naturally slow reaction kinetics, even though their corrosion is thermodynamically favorable. These include such metals as zinc, magnesium, and cadmium. While corrosion of these metals is continuous and ongoing, it happens at an acceptably slow rate. An extreme example is graphite, which releases large amounts of energy upon oxidation, but has such slow kinetics that it is effectively immune to electrochemical corrosion under normal conditions.

Passivation

Passivation refers to the spontaneous formation of an ultra-thin film of corrosion products known as passive film, on the metal's surface that act as a barrier to further oxidation. The chemical composition and microstrucure of a passive film are different from the underlying metal. Typical passive film thickness on aluminum, stainless steels and alloys is within 10 nanometers. The passive film is different from oxide layer or scale that are frequently formed at high temperatures and are in the micrometer thickness range. The passive film has the unique property of self-healing while the oxide layer or oxide scale does not. For example, when you scratch the surface of a stainless steel, the damaged passive film will be healed spontaneously by the instantaneous oxidation of chromium from the underlying metal. Passivation in natural environments such as air, water and soil at moderate pH is seen in such materials as aluminium, stainless steel, titanium, and silicon.

Passivation is primarily determined by metallurgical and environmental factors. The effect of pH is recorded using Pourbaix diagrams, but many other factors are influential. Some conditions that inhibit passivation include: high pH for aluminium and zinc, low pH or the presence of chloride ions for stainless steel, high temperature for titanium (in which case the oxide dissolves into the metal, rather than the electrolyte) and fluoride ions for silicon. On the other hand, sometimes unusual conditions can bring on passivation in materials that are normally unprotected, as the alkaline environment of concrete does for steel rebar. Exposure to a liquid metal such as mercury or hot solder can often circumvent passivation mechanisms.

Corrosion in passivated materials

Passivation is extremely useful in mitigating corrosion damage, however even a high-quality alloy will corrode if its ability to form a passivating film is hindered. Proper selection of the right grade of material for the specific environment is important for the long-lasting performance of this group of materials. If breakdown occurs in the passive film due to chemical or mechanical factors, the resulting major modes of corrosion may include pitting corrosion, crevice corrosion and stress corrosion cracking.

Pitting corrosion

Certain conditions, such as low concentrations of oxygen or high concentrations of species such as chloride which complete as anions, can interfere with a given alloy's ability to re-form a passivating film. In the worst case, almost all of the surface will remain protected, but tiny local fluctuations will degrade the oxide film in a few critical points. Corrosion at these points will be greatly amplified, and can cause corrosion pits of several types, depending upon conditions. While the corrosion pits only nucleate under fairly extreme circumstances, they can continue to grow even when conditions return to normal, since the interior of a pit is naturally deprived of oxygen and locally the pH decreases to very low values and the corrosion rate increases due to an auto-catalytic process. In extreme cases, the sharp tips of extremely long and narrow corrosion pits can cause stress concentration to the point that otherwise tough alloys can shatter; a thin film pierced by an invisibly small hole can hide a thumb sized pit from view. These problems are especially dangerous because they are difficult to detect before a part or structure fails. Pitting remains among the most common and damaging forms of corrosion in passivated alloys, but it can be prevented by control of the alloy's environment.

Weld decay and knifeline attack

Stainless steel can pose special corrosion challenges, since its passivating behavior relies on the presence of a major alloying component (Chromium, at least 11.5%). Due to the elevated temperatures of welding or during improper heat treatment, chromium carbides can form in the grain boundaries of stainless alloys. This chemical reaction robs the material of chromium in the zone near the grain boundary, making those areas much less resistant to corrosion. This creates a galvanic couple with the well-protected alloy nearby, which leads to weld decay (corrosion of the grain boundaries in the heat affected zones) in highly corrosive environments.

A stainless steel is said to be sensitized if chromium carbides are formed in the microstructure. A typical microstructure of a normalized type 304 stainless steel shows no signs of sensitization while a heavily sensitized steel shows the presence of grain boundary precipitates. The dark lines in the sensitized microstructure are networks of chromium carbides formed along the grain boundaries.[2]

Special alloys, either with low carbon content or with added carbon "getters" such as titanium and niobium (in types 321 and 347, respectively), can prevent this effect, but the latter require special heat treatment after welding to prevent the similar phenomenon of knifeline attack. As its name implies, corrosion is limited to a very narrow zone adjacent to the weld, often only a few micrometres across, making it even less noticeable.

Crevice corrosion

Crevice corrosion is a localized form of corrosion occurring in confined spaces (crevices) to which the access of the working fluid from the environment is limited and a differential aeration cell is set up, leading to the active corrosion inside the crevices. Examples of crevices are gaps and contact areas between parts, under gaskets or seals, inside cracks and seams, spaces filled with deposits and under sludge piles.

This photo shows that corrosion occurred in the crevice between the tube and tube sheet (both made of type 316 stainless steel) of a heat exchanger in a sea water desalination plant.[3]

Crevice corrosion is influenced by the crevice type (metal-metal, metal-nonmetal), crevice geometry (size, surface finish), and metallurgical and environmental factors. The susceptibility to crevice corrosion can be evaluated with ASTM standard procedures. A critical crevice corrosion temperature (CCT) is commonly used to rank a material's resistance to crevice corrosion.

Microbial corrosion

Microbial corrosion, or commonly known as microbiologically influenced corrosion (MIC), is a corrosion caused or promoted by microorganisms, usually chemoautotrophs. It can apply to both metallic and non-metallic materials, in the presence or absence of oxygen. Sulfate-reducing bacteria are active in the absence of oxygen (anaerobic); they produce hydrogen sulfide, causing sulfide stress cracking. In the presence of oxygen (aerobic), some bacteria may directly oxidize iron to iron oxides and hydroxides, other bacteria oxidize sulfur and produce sulfuric acid causing biogenic sulfide corrosion. Concentration cells can form in the deposits of corrosion products, leading to localized corrosion.

Accelerated Low Water Corrosion (ALWC) is a particularly aggressive form of MIC that affects steel piles in seawater near the low water tide mark. It is characterised by an orange sludge, which smells of hydrogen sulphide when treated with acid. Corrosion rates can be very high and design corrosion allowances can soon be exceeded leading to premature failure of the steel pile.[4] Piles that have been coating and have cathodic protection installed at the time of construction are not susceptible to ALWC. For unprotected piles, sacrificial anodes can be installed local to the affected areas to inhibit the corrosion or a complete retrofitted sacrificial anode system can be installed. Affected areas can also be treated electrochemically by using an electrode to first produce chlorine to kill the bacteria, and then to produced a calcareous deposit, which will help shield the metal from further attack.

High temperature corrosion

High temperature corrosion is chemical deterioration of a material (typically a metal) under very high temperature conditions. This non-galvanic form of corrosion can occur when a metal is subject to a high temperature atmosphere containing oxygen, sulfur or other compounds capable of oxidising (or assisting the oxidation of) the material concerned. For example, materials used in aerospace, power generation and even in car engines have to resist sustained periods at high temperature in which they may be exposed to an atmosphere containing potentially highly corrosive products of combustion.

The products of high temperature corrosion can potentially be turned to the advantage of the engineer. The formation of oxides on stainless steels, for example, can provide a protective layer preventing further atmospheric attack, allowing for a material to be used for sustained periods at both room and high temperature in hostile conditions. Such high temperature corrosion products in the form of compacted oxide layer glazes have also been shown to prevent or reduce wear during high temperature sliding contact of metallic (or metallic and ceramic) surfaces.

Methods of protection from corrosion

Surface treatments

Applied coatings

Plating, painting, and the application of enamel are the most common anti-corrosion treatments. They work by providing a barrier of corrosion-resistant material between the damaging environment and the (often cheaper, tougher, and/or easier-to-process) structural material. Aside from cosmetic and manufacturing issues, there are tradeoffs in mechanical flexibility versus resistance to abrasion and high temperature. Platings usually fail only in small sections, and if the plating is more noble than the substrate (for example, chromium on steel), a galvanic couple will cause any exposed area to corrode much more rapidly than an unplated surface would. For this reason, it is often wise to plate with active metal such as zinc or cadmium. Painting either by roller or brush is more desirable for tight spaces; spray would be better for larger coating areas such as steel decks and waterfront applications. Flexible polyurethane coatings, like Durabak-M26 for example, can provide an anti-corrosive seal with a highly durable slip resistant membrane. Painted coatings are relatively easy to apply and have fast drying times although temperature and humidity may cause dry times to vary.

Reactive coatings

If the environment is controlled (especially in recirculating systems), corrosion inhibitors can often be added to it. These form an electrically insulating and/or chemically impermeable coating on exposed metal surfaces, to suppress electrochemical reactions. Such methods obviously make the system less sensitive to scratches or defects in the coating, since extra inhibitors can be made available wherever metal becomes exposed. Chemicals that inhibit corrosion include some of the salts in hard water (Roman water systems are famous for their mineral deposits), chromates, phosphates, polyaniline, other conducting polymers and a wide range of specially-designed chemicals that resemble surfactants (i.e. long-chain organic molecules with ionic end groups).

Anodization

Aluminium alloys often undergo a surface treatment. Electrochemical conditions in the bath are carefully adjusted so that uniform pores several nanometers wide appear in the metal's oxide film. These pores allow the oxide to grow much thicker than passivating conditions would allow. At the end of the treatment, the pores are allowed to seal, forming a harder-than-usual surface layer. If this coating is scratched, normal passivation processes take over to protect the damaged area. Anodizing is very resilient to weathering and corrosion, so it is commonly used for building facades and other areas that the surface will come into regular contact with the elements. Whilst being resilient, it must be cleaned frequently. If left without cleaning Panel Edge Staining will naturally occur.

Biofilm coatings

A new form of protection has been developed by applying certain species of bacterial films to the surface of metals in highly corrosive environments. This process increases the corrosion resistance substantially. Alternatively, antimicrobial-producing biofilms can be used to inhibit mild steel corrosion from sulfate-reducing bacteria.[5]

Controlled permeability formwork

Controlled permeability formwork (CPF) is a method of preventing the corrosion of reinforcement by naturally enhancing the durability of the cover during concrete placement. CPF has been used in environments to combat the effects of carbonation, chlorides, frost and abrasion.

Cathodic protection

Cathodic protection (CP) is a technique to control the corrosion of a metal surface by making that surface the cathode of an electrochemical cell. Cathodic protection systems are most commonly used to protect steel, water, and fuel pipelines and tanks; steel pier piles, ships, and offshore oil platforms.

Sacrificial anode protection

For effective CP, the potential of the steel surface is polarized (pushed) more negative until the metal surface has a uniform potential. With a uniform potential, the driving force for the corrosion reaction is halted. For galvanic CP systems, the anode material corrodes under the influence of the steel, and eventually it must be replaced. The polarization is caused by the current flow from the anode to the cathode, driven by the difference in electrochemical potential between the anode and the cathode.

Impressed current cathodic protection

For larger structures, galvanic anodes cannot economically deliver enough current to provide complete protection. Impressed Current Cathodic Protection (ICCP) systems use anodes connected to a DC power source (such as a cathodic protection rectifier). Anodes for ICCP systems are tubular and solid rod shapes of various specialized materials. These include high silicon cast iron, RUST, mixed metal oxide or platinum coated titanium or niobium coated rod and wires.

Anodic protection

Anodic protection impresses anodic current on the structure to be protected (opposite to the cathodic protection). It is appropriate for metals that exhibit passivity (e.g., stainless steel) and suitably small passive current over a wide range of potentials. It is used in aggressive environments, e.g., solutions of sulfuric acid.

Economic impact

The US Federal Highway Administration released a study, entitled Corrosion Costs and Preventive Strategies in the United States, in 2002 on the direct costs associated with metallic corrosion in nearly every U.S. industry sector. The study showed that for 1998 the total annual estimated direct cost of corrosion in the U.S. was approximately $276 billion (approximately 3.2% of the US gross domestic product).[6]

Rust is one of the most common causes of bridge accidents. As rust has a much higher volume than the originating mass of iron, its build-up can also cause failure by forcing apart adjacent parts. It was the cause of the collapse of the Mianus river bridge in 1983, when the bearings rusted internally and pushed one corner of the road slab off its support. Three drivers on the roadway at the time died as the slab fell into the river below. The following NTSB investigation showed that a drain in the road had been blocked for road re-surfacing, and had not been unblocked so that runoff water penetrated the support hangers. It was also difficult for maintenance engineers to see the bearings from the inspection walkway. Rust was also an important factor in the Silver Bridge disaster of 1967 in West Virginia, when a steel suspension bridge collapsed in less than a minute, killing 46 drivers and passengers on the bridge at the time.

Similarly, corrosion of concrete-covered steel and iron can cause the concrete to spall, creating severe structural problems. It is one of the most common failure modes of reinforced concrete bridges. Measuring instruments based on the half-cell potential are able to detect the potential corrosion spots before total failure of the concrete structure is reached.

Corrosion in nonmetals

Most ceramic materials are almost entirely immune to corrosion. The strong ionic and/or covalent bonds that hold them together leave very little free chemical energy in the structure; they can be thought of as already corroded. When corrosion does occur, it is almost always a simple dissolution of the material or chemical reaction, rather than an electrochemical process. A common example of corrosion protection in ceramics is the lime added to soda-lime glass to reduce its solubility in water; though it is not nearly as soluble as pure sodium silicate, normal glass does form sub-microscopic flaws when exposed to moisture. Due to its brittleness, such flaws cause a dramatic reduction in the strength of a glass object during its first few hours at room temperature.

Corrosion of polymers

Polymer degradation is due to a wide array of complex and often poorly-understood physiochemical processes. These are strikingly different from the other processes discussed here, and so the term "corrosion" is only applied to them in a loose sense of the word. Because of their large molecular weight, very little entropy can be gained by mixing a given mass of polymer with another substance, making them generally quite difficult to dissolve. While dissolution is a problem in some polymer applications, it is relatively simple to design against. A more common and related problem is swelling, where small molecules infiltrate the structure, reducing strength and stiffness and causing a volume change. Conversely, many polymers (notably flexible vinyl) are intentionally swelled with plasticizers, which can be leached out of the structure, causing brittleness or other undesirable changes. The most common form of degradation, however, is a decrease in polymer chain length. Mechanisms which break polymer chains are familiar to biologists because of their effect on DNA: ionizing radiation (most commonly ultraviolet light), free radicals, and oxidizers such as oxygen, ozone, and chlorine. Ozone cracking is a well-known problem affecting natural rubber for example. Additives can slow these process very effectively, and can be as simple as a UV-absorbing pigment (i.e., titanium dioxide or carbon black). Plastic shopping bags often do not include these additives so that they break down more easily as litter.

Corrosion of glasses

Glass disease is the corrosion of silicate glasses in aqueous solutions. It is governed by two mechanisms: diffusion-controlled leaching (ion exchange) and glass network hydrolytic dissolution.[7] Both corrosion mechanisms strongly depend on the pH of contacting solution: the rate of ion exchange decreases with pH as 10-0.5pH whereas the rate of hydrolytic dissolution increases with pH as 100.5pH [8]

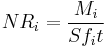

Mathematically, corrosion rates of glasses are characterised by normalised corrosion rates of elements NRi (g/cm2 d) which are determined as the ratio of total amount of released species into the water Mi (g) to the water-contacting surface area S (cm2), time of contact t (days) and weight fraction content of the element in the glass fi:

.

.

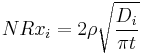

The overall corrosion rate is a sum of contributions from both mechanisms (leaching + dissolution) NRi=Nrxi+NRh. Diffusion-controlled leaching (ion exchange) is characteristic of the initial phase of corrosion and involves replacement of alkali ions in the glass by a hydronium (H3O+) ion from the solution. It causes an ion-selective depletion of near surface layers of glasses and gives an inverse square root dependence of corrosion rate with exposure time. The diffusion controlled normalised leaching rate of cations from glasses (g/cm2 d) is given by:

,

,

where t is time, Di is the i-th cation effective diffusion coefficient (cm2/d), which depends on pH of contacting water as Di = Di0·10-pH, and ρ is the density of the glass (g/cm3).

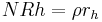

Glass network dissolution is characteristic of the later phases of corrosion and causes a congruent release of ions into the water solution at a time-independent rate in dilute solutions (g/cm2 d):

,

,

where rh is the stationary hydrolysis (dissolution) rate of the glass (cm/d). In closed systems the consumption of protons from the aqueous phase increases the pH and causes a fast transition to hydrolysis.[9] However further silica saturation of solution impedes hydrolysis and causes the glass to return to an ion-exchange, e.g. diffusion-controlled regime of corrosion.

In typical natural conditions normalised corrosion rates of silicate glasses are very low and are of the order of 10−7 - 10−5 g/cm2 d. The very high durability of silicate glasses in water makes them suitable for hazardous and nuclear waste immobilisation.

Glass corrosion tests

There exist numerous standardized procedures for measuring the corrosion (also called chemical durability) of glasses in neutral, basic, and acidic environments, under simulated environmental conditions, in simulated body fluid, at high temperature and pressure,[11] and under other conditions.

In the standard procedure ISO 719[12] a test of the extraction of water soluble basic compounds under neutral conditions is described: 2 g glass, particle size 300-500 μm, is kept for 60 min in 50 ml de-ionized water of grade 2 at 98°C. 25 ml of the obtained solution is titrated against 0.01 mol/l HCl solution. The volume of HCl needed for neutralization is recorded and classified following the values in the table below.

| 0.01M HCl needed to neutralize extracted basic oxides, ml |

Extracted Na2O equivalent, μg |

Hydrolytic class |

|---|---|---|

| to 0.1 | to 31 | 1 |

| above 0.1 to 0.2 | above 31 to 62 | 2 |

| above 0.2 to 0.85 | above 62 to 264 | 3 |

| above 0.85 to 2.0 | above 264 to 620 | 4 |

| above 2.0 to 3.5 | above 620 to 1085 | 5 |

| above 3.5 | above 1085 | >5 |

Notable Corrosion Scientists and Engineers

Herbert H. Uhlig, electrochemistry/physical chemistry (MIT)

Pierre R. Roberge, physical chemistry, chemical/materials engineering (Royal Military College of Canada)

Robert M. Burns (1890 - 1976), physical chemistry (Bell Telephone Laboratories)

Ulick Richardson Evans (1889 - 1980), electrochemistry (Canbridge University)

Carl Wagner, physical chemistry (MIT, Max Planck Institute of Physical Chemistry)

Alexander Frumkin, electrochemistry (Moscow University)

Colin G. Fink (1881 - 1953), electrochemistry, chemical engineering (Columbia University)

George H. Young (1909 - 1961) electrochemistry (Mellon Institute of Industrial Research)

Ronald G. Ballinger, nuclear/materials science and engineering (MIT)

R. Winston Revie, metallurgical engineering (CANMET Materials Technology Laboratory)

Florian B. Mansfeld, Material Science and Engineering (University of Southern California)

See also

- Anaerobic corrosion

- Chemical hazard label

- Controlled Permeability Formwork

- Copper band corrosion.

- Corrosion in space

- Electronegativity

- Electrical resistivity measurement of concrete

- Environmental stress fracture

- Forensic engineering

- FRP tanks and vessels

- Hydrogen analyzer

- Kelvin probe force microscope

- Oxidation potential

- Redox

- Reduction potential

- Periodic table

- Rouging

- Salt spray test

- Society of Tribologists and Lubrication Engineers

- Stress corrosion cracking

- Tribocorrosion

- Zinc pest

References

- ^ Galvanic Corrosion

- ^ Intergranular Corrosion

- ^ Crevice Corrosion

- ^ Management of Accelerated Low Water Corrosion in Steel Maritime Structures, JE Breakell, M Siegwart, K Foster, D Marshall, M Hodgson, R Cottis, S Lyon. ISBN 0-86017-634-7

- ^ R. Zuo, D. Örnek, B.C. Syrett, R.M. Green, C.-H. Hsu, F.B. Mansfeld and T.K. Wood, Inhibiting mild steel corrosion from sulfate-reducing bacteria using antimicrobial-producing biofilms in Three-Mile-Island process water Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. (2004) 64:275–283 http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00253-003-1403-7

- ^ FHWA Report Number: FHWA-RD-01-156.

- ^ A.K. Varshneya. Fundamentals of inorganic glasses. Society of Glass Technology, Sheffield, 682pp. (2006).

- ^ M.I. Ojovan, W.E. Lee. New Developments in Glassy Nuclear Wasteforms. Nova Science Publishers, New York, 136pp. (2007).

- ^ Corrosion of Glass, Ceramics and Ceramic Superconductors. Edited by: D.E. Clark, B.K. Zoitos, William Andrew Publishing/Noyes, 672pp. (1992).

- ^ Calculation of the Chemical Durability (Hydrolytic Class) of Glasses

- ^ Vapor Hydration Testing (VHT)

- ^ International Organization for Standardization, Procedure 719 (1985)

- Jones, Denny (1996). Principles and Prevention of Corrosion (2nd edition ed.). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-359993-0.

- Working Safely with Corrosive Chemicals

External links

- NACE International -Professional society for corrosion engineers ( NACE )

- efcweb.org - European Federation of Corrosion

- Metal Corrosion - Corrosion Theory

- Electrochemistry of corrosion

- A comprehensive 3.4-Mb pdf handbook "Corrosion Prevention and Control", 2006, 296 pages, US DoD, here

- How do you remove and prevent flash rust on stainless steel? Article about the preventions of flash rust

- DoITPoMS Teaching and Learning Package- "Kinetics of Aqueous Corrosion"