Correlation and dependence

In statistics, dependence refers to any statistical relationship between two random variables or two sets of data. Correlation refers to any of a broad class of statistical relationships involving dependence.

Familiar examples of dependent phenomena include the correlation between the physical statures of parents and their offspring, and the correlation between the demand for a product and its price. Correlations are useful because they can indicate a predictive relationship that can be exploited in practice. For example, an electrical utility may produce less power on a mild day based on the correlation between electricity demand and weather. In this example there is a causal relationship, because extreme weather causes people to use more electricity for heating or cooling; however, statistical dependence is not sufficient to demonstrate the presence of such a causal relationship.

Formally, dependence refers to any situation in which random variables do not satisfy a mathematical condition of probabilistic independence. In loose usage, correlation can refer to any departure of two or more random variables from independence, but technically it refers to any of several more specialized types of relationship between mean values. There are several correlation coefficients, often denoted ρ or r, measuring the degree of correlation. The most common of these is the Pearson correlation coefficient, which is sensitive only to a linear relationship between two variables (which may exist even if one is a nonlinear function of the other). Other correlation coefficients have been developed to be more robust than the Pearson correlation — that is, more sensitive to nonlinear relationships.[1][2][3]

Pearson's product-moment coefficient

The most familiar measure of dependence between two quantities is the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient, or "Pearson's correlation." It is obtained by dividing the covariance of the two variables by the product of their standard deviations. Karl Pearson developed the coefficient from a similar but slightly different idea by Francis Galton.[4]

The population correlation coefficient ρX,Y between two random variables X and Y with expected values μX and μY and standard deviations σX and σY is defined as:

where E is the expected value operator, cov means covariance, and, corr a widely used alternative notation for Pearson's correlation.

The Pearson correlation is defined only if both of the standard deviations are finite and both of them are nonzero. It is a corollary of the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality that the correlation cannot exceed 1 in absolute value. The correlation coefficient is symmetric: corr(X,Y) = corr(Y,X).

The Pearson correlation is +1 in the case of a perfect positive (increasing) linear relationship (correlation), −1 in the case of a perfect decreasing (negative) linear relationship (anticorrelation),[5] and some value between −1 and 1 in all other cases, indicating the degree of linear dependence between the variables. As it approaches zero there is less of a relationship (closer to uncorrelated). The closer the coefficient is to either −1 or 1, the stronger the correlation between the variables.

If the variables are independent, Pearson's correlation coefficient is 0, but the converse is not true because the correlation coefficient detects only linear dependencies between two variables. For example, suppose the random variable X is symmetrically distributed about zero, and Y = X2. Then Y is completely determined by X, so that X and Y are perfectly dependent, but their correlation is zero; they are uncorrelated. However, in the special case when X and Y are jointly normal, uncorrelatedness is equivalent to independence.

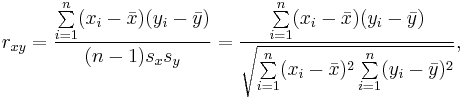

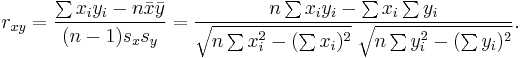

If we have a series of n measurements of X and Y written as xi and yi where i = 1, 2, ..., n, then the sample correlation coefficient can be used to estimate the population Pearson correlation r between X and Y. The sample correlation coefficient is written

where x and y are the sample means of X and Y, and sx and sy are the sample standard deviations of X and Y.

This can also be written as:

If x and y are measurements that contain measurement error, as commonly happens in biological systems, the realistic limits on the correlation coefficient are not -1 to +1 but a smaller range.[6]

Rank correlation coefficients

Rank correlation coefficients, such as Spearman's rank correlation coefficient and Kendall's rank correlation coefficient (τ) measure the extent to which, as one variable increases, the other variable tends to increase, without requiring that increase to be represented by a linear relationship. If, as the one variable increases, the other decreases, the rank correlation coefficients will be negative. It is common to regard these rank correlation coefficients as alternatives to Pearson's coefficient, used either to reduce the amount of calculation or to make the coefficient less sensitive to non-normality in distributions. However, this view has little mathematical basis, as rank correlation coefficients measure a different type of relationship than the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient, and are best seen as measures of a different type of association, rather than as alternative measure of the population correlation coefficient.[7][8]

To illustrate the nature of rank correlation, and its difference from linear correlation, consider the following four pairs of numbers (x, y):

- (0, 1), (10, 100), (101, 500), (102, 2000).

As we go from each pair to the next pair x increases, and so does y. This relationship is perfect, in the sense that an increase in x is always accompanied by an increase in y. This means that we have a perfect rank correlation, and both Spearman's and Kendall's correlation coefficients are 1, whereas in this example Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient is 0.7544, indicating that the points are far from lying on a straight line. In the same way if y always decreases when x increases, the rank correlation coefficients will be −1, while the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient may or may not be close to -1, depending on how close the points are to a straight line. Although in the extreme cases of perfect rank correlation the two coefficients are both equal (being both +1 or both −1) this is not in general so, and values of the two coefficients cannot meaningfully be compared.[7] For example, for the three pairs (1, 1) (2, 3) (3, 2) Spearman's coefficient is 1/2, while Kendall's coefficient is 1/3.

Other measures of dependence among random variables

The information given by a correlation coefficient is not enough to define the dependence structure between random variables. The correlation coefficient completely defines the dependence structure only in very particular cases, for example when the distribution is a multivariate normal distribution. (See diagram above.) In the case of elliptical distributions it characterizes the (hyper-)ellipses of equal density, however, it does not completely characterize the dependence structure (for example, a multivariate t-distribution's degrees of freedom determine the level of tail dependence).

Distance correlation and Brownian covariance / Brownian correlation [9][10] were introduced to address the deficiency of Pearson's correlation that it can be zero for dependent random variables; zero distance correlation and zero Brownian correlation imply independence.

The correlation ratio is able to detect almost any functional dependency, and the entropy-based mutual information, total correlation and dual total correlation are capable of detecting even more general dependencies. These are sometimes referred to as multi-moment correlation measures, in comparison to those that consider only second moment (pairwise or quadratic) dependence.

The polychoric correlation is another correlation applied to ordinal data that aims to estimate the correlation between theorised latent variables.

One way to capture a more complete view of dependence structure is to consider a copula between them.

Sensitivity to the data distribution

The degree of dependence between variables X and Y does not depend on the scale on which the variables are expressed. That is, if we are analyzing the relationship between X and Y, most correlation measures are unaffected by transforming X to a + bX and Y to c + dY, where a, b, c, and d are constants. This is true of some correlation statistics as well as their population analogues. Some correlation statistics, such as the rank correlation coefficient, are also invariant to monotone transformations of the marginal distributions of X and/or Y.

Most correlation measures are sensitive to the manner in which X and Y are sampled. Dependencies tend to be stronger if viewed over a wider range of values. Thus, if we consider the correlation coefficient between the heights of fathers and their sons over all adult males, and compare it to the same correlation coefficient calculated when the fathers are selected to be between 165 cm and 170 cm in height, the correlation will be weaker in the latter case.

Various correlation measures in use may be undefined for certain joint distributions of X and Y. For example, the Pearson correlation coefficient is defined in terms of moments, and hence will be undefined if the moments are undefined. Measures of dependence based on quantiles are always defined. Sample-based statistics intended to estimate population measures of dependence may or may not have desirable statistical properties such as being unbiased, or asymptotically consistent, based on the spatial structure of the population from which the data were sampled.

Correlation matrices

The correlation matrix of n random variables X1, ..., Xn is the n × n matrix whose i,j entry is corr(Xi, Xj). If the measures of correlation used are product-moment coefficients, the correlation matrix is the same as the covariance matrix of the standardized random variables Xi / σ (Xi) for i = 1, ..., n. This applies to both the matrix of population correlations (in which case "σ" is the population standard deviation), and to the matrix of sample correlations (in which case "σ" denotes the sample standard deviation). Consequently, each is necessarily a positive-semidefinite matrix.

The correlation matrix is symmetric because the correlation between Xi and Xj is the same as the correlation between Xj and Xi.

Common misconceptions

Correlation and causality

The conventional dictum that "correlation does not imply causation" means that correlation cannot be used to infer a causal relationship between the variables.[11] This dictum should not be taken to mean that correlations cannot indicate the potential existence of causal relations. However, the causes underlying the correlation, if any, may be indirect and unknown, and high correlations also overlap with identity relations (tautologies), where no causal process exists. Consequently, establishing a correlation between two variables is not a sufficient condition to establish a causal relationship (in either direction). For example, one may observe a correlation between an ordinary alarm clock ringing and daybreak, though there is no direct causal relationship between these events.

A correlation between age and height in children is fairly causally transparent, but a correlation between mood and health in people is less so. Does improved mood lead to improved health, or does good health lead to good mood, or both? Or does some other factor underlie both? In other words, a correlation can be taken as evidence for a possible causal relationship, but cannot indicate what the causal relationship, if any, might be.

Correlation and linearity

The Pearson correlation coefficient indicates the strength of a linear relationship between two variables, but its value generally does not completely characterize their relationship. In particular, if the conditional mean of Y given X, denoted E(Y|X), is not linear in X, the correlation coefficient will not fully determine the form of E(Y|X).

The image on the right shows scatterplots of Anscombe's quartet, a set of four different pairs of variables created by Francis Anscombe.[12] The four y variables have the same mean (7.5), standard deviation (4.12), correlation (0.816) and regression line (y = 3 + 0.5x). However, as can be seen on the plots, the distribution of the variables is very different. The first one (top left) seems to be distributed normally, and corresponds to what one would expect when considering two variables correlated and following the assumption of normality. The second one (top right) is not distributed normally; while an obvious relationship between the two variables can be observed, it is not linear. In this case the Pearson correlation coefficient does not indicate that there is an exact functional relationship: only the extent to which that relationship can be approximated by a linear relationship. In the third case (bottom left), the linear relationship is perfect, except for one outlier which exerts enough influence to lower the correlation coefficient from 1 to 0.816. Finally, the fourth example (bottom right) shows another example when one outlier is enough to produce a high correlation coefficient, even though the relationship between the two variables is not linear.

These examples indicate that the correlation coefficient, as a summary statistic, cannot replace visual examination of the data. Note that the examples are sometimes said to demonstrate that the Pearson correlation assumes that the data follow a normal distribution, but this is not correct.[4]

The coefficient of determination generalizes the correlation coefficient for relationships beyond simple linear regression.

Bivariate normal distribution

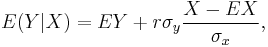

If a pair (X, Y) of random variables follows a bivariate normal distribution, the conditional mean E(X|Y) is a linear function of Y, and the conditional mean E(Y|X) is a linear function of X. The correlation coefficient r between X and Y, along with the marginal means and variances of X and Y, determines this linear relationship:

where EX and EY are the expected values of X and Y, respectively, and σx and σy are the standard deviations of X and Y, respectively.

Partial correlation

If a population or data-set is characterized by more than two variables, a partial correlation coefficient measures the strength of dependence between a pair of variables that is not accounted for by the way in which they both change in response to variations in a selected subset of the other variables.

See also

- Association (statistics)

- Autocorrelation

- Canonical correlation

- Coefficient of determination

- Concordance correlation coefficient

- Cophenetic correlation

- Copula

- Correlation function

- Cross-correlation

- Ecological correlation

- Fraction of variance unexplained

- Genetic correlation

- Goodman and Kruskal's lambda

- Illusory correlation

- Interclass correlation

- Intraclass correlation

- Linear correlation (wikiversity)

- Modifiable areal unit problem

- Multiple correlation

- Point-biserial correlation coefficient

- Statistical arbitrage

- Subindependence

References

- ^ Frederick Emory Croxton, Dudley Johnstone Cowden and Sidney Klein; Applied general statistics, page 625

- ^ Cornelius Frank Dietrich; Uncertainty, calibration, and probability : the statistics of scientific and industrial measurement, Page 331

- ^ Alexander Craig Aitken; Statistical mathematics, Page 95

- ^ a b J. L. Rodgers and W. A. Nicewander. Thirteen ways to look at the correlation coefficient. The American Statistician, 42(1):59–66, February 1988.

- ^ Dowdy, S. and Wearden, S. (1983). "Statistics for Research", Wiley. ISBN 0471086029 pp 230

- ^ Francis, DP; Coats AJ, Gibson D (1999). "How high can a correlation coefficient be?". Int J Cardiol 69: 185–199. doi:10.1016/S0167-5273(99)00028-5.

- ^ a b Yule, G.U and Kendall, M.G. (1950), "An Introduction to the Theory of Statistics", 14th Edition (5th Impression 1968). Charles Griffin & Co. pp 258–270

- ^ Kendall, M. G. (1955) "Rank Correlation Methods", Charles Griffin & Co.

- ^ Székely, G. J. Rizzo, M. L. and Bakirov, N. K. (2007). "Measuring and testing independence by correlation of distances", Annals of Statistics, 35/6, 2769–2794. doi: 10.1214/009053607000000505 Reprint

- ^ Székely, G. J. and Rizzo, M. L. (2009). "Brownian distance covariance", Annals of Applied Statistics, 3/4, 1233–1303. doi: 10.1214/09-AOAS312 Reprint

- ^ Aldrich, John (1995). "Correlations Genuine and Spurious in Pearson and Yule". Statistical Science 10 (4): 364–376. doi:10.1214/ss/1177009870. JSTOR 2246135.

- ^ Anscombe, Francis J. (1973). "Graphs in statistical analysis". The American Statistician 27: 17–21. doi:10.2307/2682899. JSTOR 2682899.

Further reading

- Cohen, J., Cohen P., West, S.G., & Aiken, L.S. (2002). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (3rd ed.). Psychology Press. ISBN 0805822232.

External links

- Earliest Uses: Correlation - gives basic history and references.

- Understanding Correlation - Introductory material by a U. of Hawaii Prof.

- Statsoft Electronic Textbook

- Pearson's Correlation Coefficient - How to calculate it quickly

- Learning by Simulations - The distribution of the correlation coefficient

- Correlation measures the strength of a linear relationship between two variables.

- MathWorld page on (cross-) correlation coefficient(s) of a sample.

- Compute Significance between two correlations - A useful website if one wants to compare two correlation values.

- A MATLAB Toolbox for computing Weighted Correlation Coefficients

- Proof that the Sample Bivariate Correlation Coefficient has Limits ±1

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

![\rho_{X,Y}=\mathrm{corr}(X,Y)={\mathrm{cov}(X,Y) \over \sigma_X \sigma_Y} ={E[(X-\mu_X)(Y-\mu_Y)] \over \sigma_X\sigma_Y},](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/076d3820a46afe55ee680f3c85e34c76.png)