Continuous geometry

In mathematics, continuous geometry is an analogue of complex projective geometry introduced by von Neumann (1936, 1998), where instead of the dimension of a subspace being in a discrete set 0, 1, ..., n, it can be an element of the unit interval [0,1]. Von Neumann was motivated by his discovery of von Neumann algebras with a dimension function taking a continuous range of dimensions, and the first example of a continuous geometry other than projective space was the projections of the hyperfinite type II factor.

Contents |

Definition

Menger and Birkhoff gave axioms for projective geometry in terms of the lattice of linear subspaces of projective space. Von Neumann's axioms for continuous geometry are a weakened form of these axioms.

A continuous geometry is a lattice L with the following properties

- L is modular.

- L is complete.

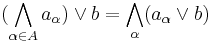

- The lattice operations ∧, ∨ satisfy a certain continuity property.

where A is a directed set and if α<β then aα <aβ, and the same condition with ∧ and ∨ reversed.

where A is a directed set and if α<β then aα <aβ, and the same condition with ∧ and ∨ reversed.

- Every element in L has a complement (not necessarily unique). A complement of an element a is an element b with a∧b=0, a∨b=1, where 0 and 1 are the minimal and maximal elements of L

- L is irreducible: this means that the only elements with unique complements are 0 and 1.

Examples

- Finite-dimensional complex projective space, or rather its set of linear subspaces, is a continuous geometry, with dimensions taking values in the discrete set {0, 1/n, 2/n, ..., 1}

- The projections of a finite type II von Neumann algebra form a continuous geometry with dimensions taking values in the unit interval [0,1].

- Kaplansky (1955) showed that any orthocomplemented complete modular lattice is a continuous geometry.

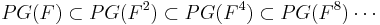

- If V is a vector space over a field (or division ring) F, then there is a natural map from the lattice PG(V) of subspaces of V to the lattice of subspaces of V⊗F2 that multiplies dimensions by 2. So we can take a direct limit of

- This has a dimension function taking values all dyadic rationals between 0 and 1. Its completion is a continuous geometry containing elements of every dimension in [0,1]. This geometry was constructed by von Neumann (1936b), and is called the continuous geometry over F.

Dimension

This section summarizes some of the results of von Neumann (1998, Part I). These results are similar to, and were motivated by, von Neumann's work on projections in von Neumann algebras.

Two elements a and b of L are called perspective, written a∼b, if they have a common complement. This is an equivalence relation on L; the proof that it is transitive is quite hard.

The equivalence classes A, B, ... of L have a total order on them defined by A≤B if there is some a in A and b in B with a≤b. (This need not hold for all a in A and b in B.)

The dimension function D from L to the unit interval is defined as follows.

- If equivalence classes A and B contain elements a and b with a∧b=0 then their sum A+B is defined to be the equivalence class of a∨b. Otherwise the sum A+B is not defined. For a positive integer n, the product nA is defined to be the sum of n copies of A, if this sum is defined.

- For equivalence classes A and B with A not {0} the integer [B:A] is defined to be the unique integer n≥0 such that B = nA+C with C<B.

- For equivalence classes A and B with A not {0} the real number (B:A) is defined to be the limit of [B:C]/[A:C] as C runs though a minimal sequence: this means that either C contains a minimal nonzero element, or an infinite sequence of nonzero elements each of which is at most half the preceding one.

- D(a) is defined to be ({a}:{1}) where {a} and {1} are the equivalence classes containing a and 1.

The image of D can be the whole unit interval, or the set of numbers 0, 1/n, 2/n, ..., 1 for some positive integer n. Two elements of L have the same image under D if and only if they are perspective, so it gives an injection from the equivalence classes to a subset of the unit interval. The dimension function D has the properties:

- If a<b then D(a)<D(b)

- D(a∨b) + D(a∧b) = D(a)+D(b)

- D(a)=0 if and only if a=0, and D(a)=1 if and only if a=1

- 0≤D(a)≤1

Coordinatization theorem

In projective geometry, the Veblen–Young theorem states that a projective geometry of dimension at least 3 is isomorphic to the projective geometry of a vector space over a division ring. This can be restated as saying that the subspaces in the projective geometry correspond to the principal right ideals of a matrix algebra over a division ring.

Von Neumann generalized this to continuous geometries, and more generally to complemented modular lattices, as follows (von Neumann 1998, Part II). His theorem states that if a complemented modular lattice L has order at least 4, then the elements of L correspond to the principal right ideals of a von Neumann regular ring. More precisely if the lattice has order n then the von Neumann regular ring can be taken to be an n by n matrix ring Mn(R) over another von Neumann regular ring R. Here a complemented modular lattice has order n if it has a homogeneous basis of n elements, where a basis is n elements a1,...an such that ai∧aj= 0 if i≠j, and a1∨...∨an=1, and a basis is called homogeneous if any two elements are perspective. The order of a lattice need not be unique; for example, any lattice has order 1. The condition that the lattice has order at least 4 corresponds to the condition that the dimension is at least 3 in the Veblen–Young theorem, as a projective space has dimension at least 3 if and only if it has a set of at least 4 independent points.

Conversely, the principal right ideals of a von Neumann regular ring form a complemented modular lattice (von Neumann 1998, Part II theorem 2.4).

Suppose that R is a von Neumann regular ring and L its lattice of principal right ideals, so that L is a complemented modular lattice. Von Neumann showed that L is a continuous geometry if and only if R is an irreducible complete rank ring.

References

- Birkhoff, Garrett (1979) [1940], Lattice theory, American Mathematical Society Colloquium Publications, 25 (3rd ed.), Providence, R.I.: American Mathematical Society, ISBN 978-0-8218-1025-5, MR598630, http://books.google.com/books?id=o4bu3ex9BdkC

- Fofanova, T.S. (2001), "Orthomodular lattice", in Hazewinkel, Michiel, Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1556080104, http://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=o/o070450

- Halperin, Israel (1960), "Introduction to von Neumann algebras and continuous geometry", Canadian Mathematical Bulletin 3: 273–288, doi:10.4153/CMB-1960-034-5, ISSN 0008-4395, MR0123923, http://www.math.ca/10.4153/CMB-1960-034-5

- Halperin, Israel (1985), "Books in Review: A survey of John von Neumann's books on continuous geometry", Order 1 (3): 301–305, doi:10.1007/BF00383607, ISSN 0167-8094, MR1554221

- Kaplansky, Irving (1955), "Any orthocomplemented complete modular lattice is a continuous geometry", Annals of Mathematics. Second Series 61 (3): 524–541, doi:10.2307/1969811, ISSN 0003-486X, JSTOR 1969811, MR0088476

- Skornyakov, L. A. (1964), Complemented modular lattices and regular rings, London: Oliver & Boyd, MR0166126, http://books.google.com/books?id=p54EAQAAIAAJ

- von Neumann, John (1936), "Continuous geometry", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 22 (2): 92–100, doi:10.1073/pnas.22.2.92, ISSN 0027-8424, JSTOR 86390, Zbl 0014.22307

- von Neumann, John (1936b), "Examples of continuous geometries", Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 22 (2): 101–108, doi:10.1073/pnas.22.2.101, JFM 62.0648.03, JSTOR 86391, PMC 1076713, PMID 16588050, http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1076713

- von Neumann, John (1998) [1960], Continuous geometry, Princeton Landmarks in Mathematics, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-05893-1, MR0120174, http://books.google.com/books?id=onE5HncE-HgC

- von Neumann, John (1962), Taub, A. H., ed., Collected works. Vol. IV: Continuous geometry and other topics, Oxford: Pergamon Press, MR0157874, http://books.google.com/books?id=HOTXAAAAMAAJ

- von Neumann, John (1981) [1937], Halperin, Israel, ed., "Continuous geometries with a transition probability", Memoirs of the American Mathematical Society 34 (252), ISBN 9780821822524, ISSN 0065-9266, MR634656, http://books.google.com/books?id=ZPkVGr8NXugC