Contiguity (probability theory)

In probability theory, two sequences of probability measures are said to be contiguous if asymptotically they share the same support. Thus the notion of contiguity extends the concept of absolute continuity to the sequences of measures.

The concept was originally introduced by Le Cam (1960) as part of his contribution to the development of abstract general asymptotic theory in mathematical statistics. Le Cam was instrumental during the period in the development of abstract general asymptotic theory in mathematical statistics. He is best known for the general concepts of local asymptotic normality and contiguity.

???[1]

Contents |

Definition

Let  be a sequence of measurable spaces, each equipped with two measures Pn and Qn.

be a sequence of measurable spaces, each equipped with two measures Pn and Qn.

- We say that Qn is contiguous with respect to Pn (denoted Qn ◁ Pn) if for every sequence An of measurable sets, Pn(An) → 0 implies Qn(An) → 0.

- The sequences Pn and Qn are said to be mutually contiguous or bi-contiguous (denoted Qn ◁▷ Pn) if both Qn is contiguous with respect to Pn and Pn is contiguous with respect to Qn. [2]

The notion of contiguity is closely related to that of absolute continuity. We say that a measure Q is absolutely continuous with respect to P (denoted Q ≪ P) if for any measurable set A, P(A) = 0 implies Q(A) = 0. That is, Q is absolutely continuous with respect to P if the support of Q is a subset of the support of P. The contiguity property replaces this requirement with an asymptotic one: Qn is contiguous with respect to Pn if the “limiting support” of Qn is a subset of the limiting support of Pn.

It is possible however that each of the measures Qn be absolutely continuous with respect to Pn, while the sequence Qn not being contiguous with respect to Pn.

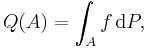

The fundamental Radon–Nikodym theorem for absolutely continuous measures states that if Q is absolutely continuous with respect to P, then Q has density with respect to P, denoted as ƒ = dQ⁄dP, such that for any measurable set A

which is interpreted as being able to “reconstruct” the measure Q from knowing the measure P and the derivative ƒ. A similar result exists for contiguous sequences of measures, and is given by the Le Cam’s third lemma.

Applications

See also

Notes

- ^ Wolfowitz J.(1974) Review of the book: "Contiguity of Probability Measures: Some Applications in Statistics. by George G. Roussas", Journal of the American Statistical Association, 69, 278–279 jstor

- ^ van der Vaart (1998)

- ^ http://www.samsi.info/200506/fmse/course-info/werker-updated-nov14.pdf

References

- Hájek, J.; Šidák, Z. (1967). Theory of rank tests. New York: Academic Press.

- Le Cam, Lucien (1960). "Locally asymptotically normal families of distributions". University of California Publications in Statistics 3: 37–98.

- Roussas, George G. (2001), "Contiguity of probability measures", in Hazewinkel, Michiel, Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1556080104, http://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=C/c120210

- van der Vaart, A. W. (1998). Asymptotic statistics. Cambridge University Press.

Additional literature

-

- Roussas, George G. (1972), Contiguity of Probability Measures: Some Applications in Statistics, CUP, ISBN 9780521090957.

- Scott, D.J. (1982) Contiguity of Probability Measures, Australian & New Zealand Journal of Statistics, 24 (1), 80–88.

External references

- Contiguity Asymptopia: 17 October 2000, David Pollard

- Asymptotic normality under contiguity in a dependence case

- A Central Limit Theorem under Contiguous Alternatives

- Superefficiency, Contiguity, LAN, Regularity, Convolution Theorems

- Testing statistical hypotheses

- Necessary and sufficient conditions for contiguity and entire asymptotic separation of probability measures R Sh Liptser et al 1982 Russ. Math. Surv. 37 107–136

- The unconscious as infinite sets By Ignacio Matte Blanco, Eric (FRW) Rayner

- "Contiguity of Probability Measures", David J. Scott, La Trobe University

- "On the Concept of Contiguity", Hall, Loynes