Computational Aeroacoustics

While the discipline of Aeroacoustics is definitely dated back to the first publication of Sir James Lighthill[1][2] in the early 1950s, the origin of Computational Aeroacoustics can only very likely be dated back to the middle of the 1980s. Probably the term Computational Aeroacoustics entered the field with a publication of Hardin and Lamkin[3] who claimed, that

"[...] the field of computational fluid mechanics has been advancing rapidly in the past few years and now offers the hope that "computational aeroacoustics," where noise is computed directly from a first principles determination of continuous velocity and vorticity fields, might be possible, [...]"

Later in a publication 1986[4] the same authors introduced the abbreviation CAA. The term was initially used for a low Mach number approach (Expansion of the acoustic perturbation field about an incompressible flow) as it is described under EIF. Later in the beginning 1990s the growing CAA community picked up the term and extensively used it for any kind of numerical method describing the noise radiation from an aeroacoustic source or the propagation of sound waves in an inhomogeneous flow field. Such numerical methods can be far field integration methods (e.g. FW-H[5][6]) as well as direct numerical methods optimized for the solutions (e.g.[7]) of a mathematical model describing the aerodynamic noise generation and/or propagation. With the rapid development of the computational resources this field has undergone spectacular progress during the last three decades.

Contents |

Methods

Direct numerical simulation (DNS) Approach to CAA

Compressible Navier-Stokes equation describes both the flow field, and the aerodynamically generated acoustic field is solved directly. This requires very high numerical resolution due to the large differences in the length scale present between the acoustic variables and the flow variables. It is computationally very demanding and unsuitable for any commercial use.

Hybrid Approach

In this approach the computational domain is split into different regions, such that the governing acoustic or flow field can be solved with different equations and numerical techniques. This would involve using two different numerical solvers, first a dedicated Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) tool and secondly an acoustic solver. The flow field is then used to calculate the acoustical sources. Both steady state (RANS, SNGR (Stochastic Noise Generation and Radiation), ...) and transient (DNS, LES, DES, URANS, ...) fluid field solutions can be used. These acoustical sources are provided to the second solver which calculates the acoustical propagation. Acoustic propagation can be calculated using one of the following methods :

- Integral Methods

- Lighthill's analogy

- Kirchhoff integral

- FW-H

- LEE

- EIF

- APE

Integral methods

There are multiple methods, which are based on a known solution of the acoustic wave equation to compute the acoustic far field of a sound source. Because a general solution for wave propagation in the free space can be written as an integral over all sources, these solutions are summarized as integral methods. The acoustic sources have to be known from some different source (e.g. a Finite Element simulation of a moving mechanical system or a fluid dynamic CFD simulation of the sources in a moving medium). The integral is taken over all sources at the retarded time (source time), which is the time at that the source is sent out the signal, which arrives now at a given observer position. Common to all integral methods is, that they cannot account for changes in the speed of sound or the average flow speed between source and observer position as they use a theoretical solution of the wave equation. When applying Lighthill's theory [1][2] to the Navier Stokes equations of Fluid mechanics, one obtains volumetric sources, whereas the other two analogies provide the far field information based on a surface integral. Acoustic analogies can be very efficient and fast, as the known solution of the wave equation is used. One far away observer takes as long as one very close observer. Common for the application of all analogies is the integration over a large number of contributions, which can lead to additional numerical problems (addition/subtraction of many large numbers with result close to zero.) Furthermore, when applying an integral method, usually the source domain is limited somehow. While in theory the sources outside have to be zero, the application can not always fulfill this condition. Especially in connection with CFD simulations, this leads to large cut-off errors. For some applications these errors even dominate the solution.

Lighthill's analogy

Also called 'Acoustic Analogy'. To obtain Lighthill's aeroacoustic analogy the governing Navier-Stokes equations are rearranged. The left hand side is a wave operator, which is applied to the density perturbation or pressure perturbation respectively. The right hand side is identified as the acoustic sources in a fluid flow, then. As Lighthill's analogy follows directly from the Navier-Stokes equations without simplification, all sources are present. Some of the sources are then identified as turbulent or laminar noise. The far-field sound pressure is then given in terms of a volume integral over the domain containing the sound source. The source term always includes physical sources and such sources, which describe the propagation in an inhomogeneous medium.

The wave operator of Lighthill's analogy is limited to constant flow conditions outside the source zone. No variation of density, speed of sound and Mach number is allowed. Different mean flow conditions are identified as strong sources with opposite sign by the analogy, once an acoustic wave passes it. Part of the acoustic wave is removed by one source and a new wave is radiated to fix the different wave speed. This often leads very large volumes with strong sources. Several modifications to Lighthill's original theory have been proposed to account for the sound-flow interaction or other effects. To improve Lighthill's analogy different quantities inside the wave operator as well as different wave operators are considered by following analogies. All of them obtain modified source terms, which sometimes allow a more clear sight on the "real" sources. The acoustic analogies of Lilley,[8] Pierce,[9] Howe[10] and Möhring[11] are only some examples for aeroacoustic analogies based on Lighthill's ideas. All acoustic analogies require a volume integration over a source term.

The major difficulty with the acoustic analogy, however, is that the sound source is not compact in supersonic flow. Errors could be encountered in calculating the sound field, unless the computational domain could be extended in the downstream direction beyond the location where the sound source has completely decayed. Furthermore, an accurate account of the retarded time-effect requires keeping a long record of the time-history of the converged solutions of the sound source, which again represents a storage problem. For realistic problems, the required storage can reach the order of 1 terabyte of data. See Lighthill's equation

Kirchhoff integral

Kirchhoff and Helmholtz showed, that the radiation of sound from a limited source region can be described by enclosing this source region by a control surface - the so called Kichhoff surface. Then the sound field inside or outside the surface, where no sources are allowed and the wave operator on the left hand side applies, can be produced as a superposition of monopoles and dipoles on the surface. The theory follows directly from the wave equation. The source strength of monopoles and dipoles on the surface can be calculated if the normal velocity (for monopoles) and the pressure (for dipoles) on the surface are known respectively. A modification of the method allows even to calculate the pressure on the surface based on the normal velocity only. The normal velocity could be given by a FE-simulation of a moving structure for instance. However, the modification to avid the acoustic pressure on the surface to be known leads to problems, when considering an enclosed volume at its resonant frequencies, which is a major issue of the implementations of their method. The Kirchhoff integral method finds for instance application in Boundary element methods (BEM). A non-zero flow velocity is accounted by considering a moving frame of reference with the outer flow speed, in which the acoustic wave propagation takes place. Repetitive applications of the method can account for obstacles. First the sound field on the surface of the obstacle is calculated and then the obstacle is introduced by adding sources on its surface to cancel the normal velocity on the surface of the obstacle. Variations of the average flow field (speed of sound, density and velocity) can be taken into account by a similar method (e.g. dual reciprocity BEM).

FW-H

The far-field integration method of Ffowcs-Williams and Hawking is based on Lighthill's acoustic analogy. However, by some mathematical modifications under the assumption of a limited source region, which is enclosed by a control surface (FW-H surface), the volume integral is avoided. Surface integrals over monopole and dipole sources remain. Different from the Kirchhoff method, these sources follow directly from the Navier-Stokes equations through Lighthill's analogy. Sources outside the FW-H surface can be accounted by an additional volume integral over quadrupole sources following from the Lighthill Tensor. However, when considering the same assumptions as Kirchhoffs linear theory, the FW-H method equals the Kirchhoff method.

Linearized Euler Equations

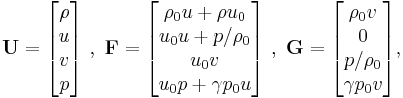

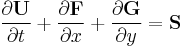

Considering small disturbances superimposed on a uniform mean flow of density  , pressure

, pressure  and velocity on x-axis

and velocity on x-axis  , the Euler equations for a two dimensional model is presented as:

, the Euler equations for a two dimensional model is presented as:

,

,

where

where  ,

,  ,

,  and

and  are the acoustic field variables,

are the acoustic field variables,  the ratio of specific heats

the ratio of specific heats  , for air at 20°C

, for air at 20°C  , and the source term

, and the source term  on the right-side represents distributed unsteady sources.

on the right-side represents distributed unsteady sources.

For high Mach number flows in compressible regimes, the acoustic propagation may be influenced by non-linearities and the LEE may no longer be the appropriate mathematical model.

EIF

Expansion about Incompressible Flow

APE

Acoustic Perturbation Equations

References

- ^ a b Lighthill, M. J., "On Sound Generated Aerodynamically, i", Proc. Roy. Soc. A, Vol. 211, 1952, pp 564-587

- ^ a b Lighthill, M. J., "On Sound Generated Aerodynamically, ii", Proc. Roy. Soc. A, Vol. 222, 1954, pp 1-32

- ^ Hardin, J.C. and Lamkin, S. L., "Aeroacoustic Computation of Cylinder Wake Flow," AIAA Journal, 22(1):51-57, 1984

- ^ Hardin, J. C. and Lamkin, S. L., "Computational aeroacoustics - Present status and future promise," IN: Aero- and hydro-acoustics; Proceedings of the Symposium, Ecully, France, July 3–6, 1985 (A87-13585 03-71). Berlin and New York, Springer-Verlag, 1986, p. 253-259.

- ^ Ffowcs Williams, "The Noise from Turbulence Convected at High Speed", Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, Vol. A255, 1963, pp. 496-503

- ^ Ffowcs Williams, J. E., and Hawkings, D. L., "Sound Generated by Turbulence and Surfaces in Arbitrary Motion", Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, Vol. A264, 1969, pp. 321-342

- ^ C. K. W. Tam, and J. C. Webb, "Dispersion-Relation-Preserving Finite Difference Schemes for Computational Acoustics", Journal of Computational Physics, Vol. 107, 1993, pp. 262-281

- ^ Lilley, G. M., "On the noise from air jets",AGARD CP 131, 13.1-13.12

- ^ Pierce, A. D., "Wave equation for the sound in fluids with unsteady inhomogeneous flow", J. Acoust. Soc. Am., 87:2292-2299, 1990

- ^ Howe, M. S., "Contributions to the theory of aerodynamic sound, with application to excess jet noise and the theory of the flute", J. Fluid Mech., 71:625-673, 1975

- ^ Möhring, W., "On vortex sound at low Mach number", Journal of Fluid Mechanics, 85:685-691,1978

- Lighthill, M. J., "A General Introduction to Aeroacoustics and Atmospheric Sounds", ICASE Report 92-52, NASA Langley Research Centre, Hampton, VA, 1992

External links

- Examples in Aeroacoustics from NASA

- Computational Aeroacoustics at the Ecole Centrale de Lyon

- Computational Aeroacoustics at the University of Leuven

- Computational Aeroacoustics at Technische Universität Berlin

- A CAA lecture script of Technische Universität Berlin