Character theory

- This article refers to the use of the term character theory in mathematics. For the media studies definition, see Character theory (Media).

In mathematics, more specifically in group theory, the character of a group representation is a function on the group which associates to each group element the trace of the corresponding matrix. The character carries the essential information about the representation in a more condensed form. Georg Frobenius initially developed representation theory of finite groups entirely based on the characters, and without any explicit matrix realization of representations themselves. This is possible because a complex representation of a finite group is determined (up to isomorphism) by its character. The situation with representations over a field of positive characteristic, so-called "modular representations", is more delicate, but Richard Brauer developed a powerful theory of characters in this case as well. Many deep theorems on the structure of finite groups use characters of modular representations.

Contents |

Applications

Characters of irreducible representations encode many important properties of a group and can thus be used to study its structure. Character theory is an essential tool in the classification of finite simple groups. Close to half of the proof of the Feit–Thompson theorem involves intricate calculations with character values. Easier, but still essential, results that use character theory include the Burnside theorem (a purely group-theoretic proof of the Burnside theorem now exists, but that proof came over half a century after Burnside's original proof), and a theorem of Richard Brauer and Michio Suzuki stating that a finite simple group cannot have a generalized quaternion group as its Sylow 2 subgroup.

Definitions

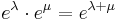

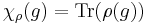

Let V be a finite-dimensional vector space over a field F and let ρ:G → GL(V) be a representation of a group G on V. The character of ρ is the function χρ: G → F given by

where  is the trace.

is the trace.

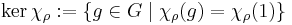

A character χρ is called irreducible if ρ is an irreducible representation. It is called linear if the dimension of ρ is 1. When G is finite and F has characteristic zero, the kernel of the character χρ is the normal subgroup:  , which is precisely the kernel of the representation ρ.

, which is precisely the kernel of the representation ρ.

Properties

- Characters are class functions, that is, they each take a constant value on a given conjugacy class.

- Isomorphic representations have the same characters. Over a field of characteristic 0, representations are isomorphic if and only if they have the same character.

- If a representation is the direct sum of subrepresentations, then the corresponding character is the sum of the characters of those subrepresentations.

- If a character of the finite group G is restricted to a subgroup H, then the result is also a character of H.

- Every character value

is a sum of n mth roots of unity, where n is the degree (that is, the dimension of the associated vector space) of the representation with character χ and m is the order of g. In particular, when F is the field of complex numbers, every such character value is an algebraic integer.

is a sum of n mth roots of unity, where n is the degree (that is, the dimension of the associated vector space) of the representation with character χ and m is the order of g. In particular, when F is the field of complex numbers, every such character value is an algebraic integer.

- If F is the field of complex numbers, and

is irreducible, then

is irreducible, then ![[G:C_G(x)]\frac{\chi(x)}{\chi(1)}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/a651c729ec5d19410db9eb949f9e928f.png) is an algebraic integer for each x in G.

is an algebraic integer for each x in G.

- If F is algebraically closed and char(F) does not divide |G|, then the number of irreducible characters of G is equal to the number of conjugacy classes of G. Furthermore, in this case, the degrees of the irreducible characters are divisors of the order of G.

Arithmetic properties

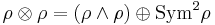

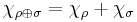

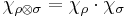

Let ρ and σ be representations of G. Then the following identities hold:

where  is the direct sum,

is the direct sum,  is the tensor product,

is the tensor product,  denotes the conjugate transpose of ρ, and Alt2 is the alternating product Alt2 (ρ) =

denotes the conjugate transpose of ρ, and Alt2 is the alternating product Alt2 (ρ) =  and Sym2 is the symmetric square, which is determined by

and Sym2 is the symmetric square, which is determined by

.

.

Character tables

The irreducible complex characters of a finite group form a character table which encodes much useful information about the group G in a compact form. Each row is labelled by an irreducible character and the entries in the row are the values of that character on the representatives of the respective conjugacy class of G. The columns are labelled by (representatives of) the conjugacy classes of G. It is customary to label the first row by the trivial character, and the first column by (the conjugacy class of) the identity. The entries of the first column are the values of the irreducible characters at the identity, the degrees of the irreducible characters. Characters of degree 1 are known as linear characters.

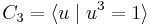

Here is the character table of  , the cyclic group with three elements and generator u:

, the cyclic group with three elements and generator u:

| (1) | (u) | (u2) | |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| χ1 | 1 | ω | ω2 |

| χ2 | 1 | ω2 | ω |

where ω is a primitive third root of unity.

The character table is always square, because the number of irreducible representations is equal to the number of conjugacy classes. The first row of the character table always consists of 1s, and corresponds to the trivial representation (the 1-dimensional representation consisting of 1×1 matrices containing the entry 1).

Orthogonality relations

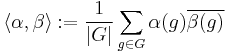

The space of complex-valued class functions of a finite group G has a natural inner-product:

where  means the complex conjugate of the value of

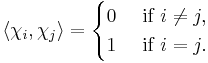

means the complex conjugate of the value of  on g. With respect to this inner product, the irreducible characters form an orthonormal basis for the space of class-functions, and this yields the orthogonality relation for the rows of the character table:

on g. With respect to this inner product, the irreducible characters form an orthonormal basis for the space of class-functions, and this yields the orthogonality relation for the rows of the character table:

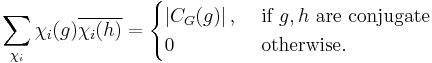

For  the orthogonality relation for columns is as follows:

the orthogonality relation for columns is as follows:

where the sum is over all of the irreducible characters  of G and the symbol

of G and the symbol  denotes the order of the centralizer of

denotes the order of the centralizer of  .

.

The orthogonality relations can aid many computations including:

- Decomposing an unknown character as a linear combination of irreducible characters.

- Constructing the complete character table when only some of the irreducible characters are known.

- Finding the orders of the centralizers of representatives of the conjugacy classes of a group.

- Finding the order of the group.

Character table properties

Certain properties of the group G can be deduced from its character table:

- The order of G is given by the sum of the squares of the entries of the first column (the degrees of the irreducible characters). (See Representation theory of finite groups#Applying Schur's lemma.) More generally, the sum of the squares of the absolute values of the entries in any column gives the order of the centralizer of an element of the corresponding conjugacy class.

- All normal subgroups of G (and thus whether or not G is simple) can be recognised from its character table. The kernel of a character χ is the set of elements g in G for which χ(g) = χ(1); this is a normal subgroup of G. Each normal subgroup of G is the intersection of the kernels of some of the irreducible characters of G.

- The derived subgroup of G is the intersection of the kernels of the linear characters of G. In particular, G is Abelian if and only if all its irreducible characters are linear.

- It follows, using some results of Richard Brauer from modular representation theory, that the prime divisors of the orders of the elements of each conjugacy class of a finite group can be deduced from its character table (an observation of Graham Higman).

The character table does not in general determine the group up to isomorphism: for example, the quaternion group Q and the dihedral group of 8 elements (D4) have the same character table. Brauer asked whether the character table, together with the knowledge of how the powers of elements of its conjugacy classes are distributed, determines a finite group up to isomorphism. In 1964, this was answered in the negative by E. C. Dade.

The linear characters form a character group, which has important number theoretic connections.

Induced characters and Frobenius reciprocity

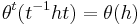

The characters discussed in this section are assumed to be complex-valued. Let H be a subgroup of the finite group G. Given a character  of G, let

of G, let  denote its restriction to H. Let

denote its restriction to H. Let  be a character of H. Ferdinand Georg Frobenius showed how to construct a character of G from

be a character of H. Ferdinand Georg Frobenius showed how to construct a character of G from  , using what is now known as Frobenius reciprocity. Since the irreducible characters of G form an orthonormal basis for the space of complex-valued class functions of G, there is a unique class function

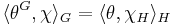

, using what is now known as Frobenius reciprocity. Since the irreducible characters of G form an orthonormal basis for the space of complex-valued class functions of G, there is a unique class function  of G with the property that

of G with the property that

for each irreducible character  of G (the leftmost inner product is for class functions of G and the rightmost inner product is for class functions of H). Since the restriction of a character of G to the subgroup H is again a character of H, this definition makes it clear that

of G (the leftmost inner product is for class functions of G and the rightmost inner product is for class functions of H). Since the restriction of a character of G to the subgroup H is again a character of H, this definition makes it clear that  is a non-negative integer combination of irreducible characters of G, so is indeed a character of G. It is known as the character of G induced from θ. The defining formula of Frobenius reciprocity can be extended to general complex-valued class functions.

is a non-negative integer combination of irreducible characters of G, so is indeed a character of G. It is known as the character of G induced from θ. The defining formula of Frobenius reciprocity can be extended to general complex-valued class functions.

Given a matrix representation ρ of H, Frobenius later gave an explicit way to construct a matrix representation of G, known as the representation induced from ρ, and written analogously as  . This led to an alternative description of the induced character

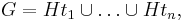

. This led to an alternative description of the induced character  . This induced character vanishes on all elements of G which are not conjugate to any element of H. Since the induced character is a class function of G, it is only now necessary to describe its values on elements of H. Writing G as a disjoint union of right cosets of H, say

. This induced character vanishes on all elements of G which are not conjugate to any element of H. Since the induced character is a class function of G, it is only now necessary to describe its values on elements of H. Writing G as a disjoint union of right cosets of H, say

and given an element h of H, the value  is precisely the sum of those

is precisely the sum of those  for which the conjugate

for which the conjugate  is also in H. Because θ is a class function of H, this value does not depend on the particular choice of coset representatives.

is also in H. Because θ is a class function of H, this value does not depend on the particular choice of coset representatives.

This alternative description of the induced character sometimes allows explicit computation from relatively little information about the embedding of H in G, and is often useful for calculation of particular character tables. When θ is the trivial character of H, the induced character obtained is known as the permutation character of G (on the cosets of H).

The general technique of character induction and later refinements found numerous applications in finite group theory and elsewhere in mathematics, in the hands of mathematicians such as Emil Artin, Richard Brauer, Walter Feit and Michio Suzuki, as well as Frobenius himself.

Mackey decomposition

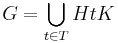

Mackey decomposition was defined and explored by George Mackey in the context of Lie groups, but is a powerful tool in the character theory and representation theory of finite groups. Its basic form concerns the way a character (or module) induced from a subgroup H of a finite group G behaves on restriction back to a (possibly different) subgroup K of G, and makes use of the decomposition of G into (H,K)-double cosets.

If

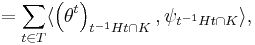

is a disjoint union, and  is a complex class function of H, then Mackey's formula states that

is a complex class function of H, then Mackey's formula states that

where  is the class function of

is the class function of  defined by

defined by  for each h in H. There is a similar formula for the restriction of an induced module to a subgroup, which holds for representations over any ring, and has applications in a wide variety of algebraic and topological contexts.

for each h in H. There is a similar formula for the restriction of an induced module to a subgroup, which holds for representations over any ring, and has applications in a wide variety of algebraic and topological contexts.

Mackey decomposition, in conjunction with Frobenius reciprocity, yields a well-known and useful formula for the inner product of two class functions θ and ψ induced from respective subgroups H and K, whose utility lies in the fact that it only depends on how conjugates of H and K intersect each other. The formula (with its derivation) is:

(where T is a full set of (H,K)- double coset representatives, as before). This formula is often used when θ and ψ are linear characters, in which case all the inner products appearing in the right hand sum are either 1 or 0, depending on whether or not the linear characters θt and ψ have the same restriction to  . If θ and ψ are both trivial characters, then the inner product simplifies to |T|.

. If θ and ψ are both trivial characters, then the inner product simplifies to |T|.

"Twisted" dimension

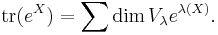

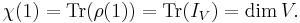

One may interpret the character of a representation as the "twisted" dimension of a vector space.[1] Treating the character as a function of the elements of the group  , its value at the identity is the dimension of the space, since

, its value at the identity is the dimension of the space, since  Accordingly, one can view the other values of the character as "twisted" dimensions.

Accordingly, one can view the other values of the character as "twisted" dimensions.

One can find analogs or generalizations of statements about dimensions to statements about characters or representations. A sophisticated example of this occurs in the theory of monstrous moonshine: the j-invariant is the graded dimension of an infinite-dimensional graded representation of the Monster group, and replacing the dimension with the character gives the McKay–Thompson series for each element of the Monster group.[1]

Characters of Lie groups and Lie algebras

Let  be a Lie group with associated Lie algebra

be a Lie group with associated Lie algebra  , and let

, and let  and

and  be the Cartan subgroup/subalgebra.

be the Cartan subgroup/subalgebra.

Let  be a representation of

be a representation of  If we write the weight spaces of

If we write the weight spaces of  as

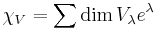

as  , then, we can define the formal character of the Lie group and Lie algebra as

, then, we can define the formal character of the Lie group and Lie algebra as

where we sum over all weights of the weight lattice. In the above expression,  is a formal object satisfying

is a formal object satisfying  . This formal character is related to the regular one for other groups. If

. This formal character is related to the regular one for other groups. If  , where

, where  is the Cartan subgroup of

is the Cartan subgroup of  (that is,

(that is,  ), then

), then

The above discussion for the decomposition of tensor products and other representations continue to hold true for the formal character. In the case of a compact Lie group, the Weyl character formula can be used to calculate the formal character.

See also

- Association schemes, a combinatorial generalization of group-character theory.

- Clifford theory, introduced by A. H. Clifford in 1937, yields information about the restriction of a complex irreducible character of a finite group G to a normal subgroup N.

References

- ^ a b (Gannon 2006)

- Lecture 2 of Fulton, William; Harris, Joe (1991), Representation theory. A first course, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, Readings in Mathematics, 129, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-97495-8, MR1153249, ISBN 978-0-387-97527-6

- Isaacs, I.M. (1994). Character Theory of Finite Groups (Corrected reprint of the 1976 original, published by Academic Press. ed.). Dover. ISBN 0-486-68014-2.

- Gannon, Terry (2006). Moonshine beyond the Monster: The Bridge Connecting Algebra, Modular Forms and Physics. ISBN 0-521-83531-3

- James, Gordon; Liebeck, Martin (2001). Representations and Characters of Groups (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-00392-X.

- Serre, Jean-Pierre (1977). Linear Representations of Finite Groups. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-90190-6.

External links

- Character at PlanetMath.

![\chi_{{\scriptscriptstyle \rm{Alt}^2} \rho}(g) = \frac{1}{2} \left[

\left(\chi_\rho (g) \right)^2 - \chi_\rho (g^2) \right]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/e1d002dedb5300de2d2d155a66802c7d.png)

![\chi_{{\scriptscriptstyle \rm{Sym}^2} \rho}(g) = \frac{1}{2} \left[

\left(\chi_\rho (g) \right)^2 %2B \chi_\rho (g^2) \right]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/7aece17caa2a192c551f79580e52fee8.png)

![\left( \theta^{G}\right)_K = \sum_{ t \in T} \left([\theta^{t}]_{t^{-1}Ht \cap K}\right)^{K},](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/176cd27f70f1c425a05183f51538a940.png)

![= \langle \left(\theta^{G}\right)_{K},\psi \rangle =

\sum_{ t \in T} \langle \left([\theta^{t}]_{t^{-1}Ht \cap K}\right)^{K},

\psi \rangle](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/6ecc1ab456afb9f7f137232bcce0e17b.png)