Cant (road/rail)

The cant of a railway track (also referred to as superelevation) or a road (sometimes referred to as camber or cross slope) is the difference in elevation (height) between the two edges. This is normally done where the railway or road is curved; raising the outer rail or the outer edge of the road provides a banked turn, allowing vehicles to traverse the curve at higher speeds than would otherwise be possible.

Contents |

Rail

On railways, cant helps a train steer around a curve, keeping the wheel flanges from touching the rails, minimizing friction and wear.

The main functions of cant are to:

- better distribute load across both rails

- reduce rail- and wheel-wear

- neutralize the effect of lateral forces

- improve passenger comfort

The amount of cant which is optimal depends on the expected speed of the trains. However, it may be necessary to select a compromise value at design time, for example if slow-moving trains may occasionally use tracks intended for high-speed trains.

Generally the aim is for trains to run without flange contact, which also depends on the tyre profile of the wheels. Allowance has to be made for the different speeds of trains. Slower trains will tend to make flange contact with the inner rail on curves, while faster trains will tend to ride outwards and make contact with the outer rail. Either contact causes wear and tear and may lead to derailment. Many high-speed lines do not permit slower freight trains, particularly with heavier axle loads. In some cases, the impact is reduced by the use of flange lubrication.

Ideally, the track should have sleepers (railroad ties) at a closer spacing and a greater depth of ballast to accommodate the increased forces exerted in the curve.

At the ends of a curve, the amount of cant cannot change from zero to its maximum immediately. It must change (ramp) gradually in a track transition curve. The length of the transition depends on the maximum allowable speed – the higher the speed, the greater length is required.

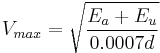

In the United States, maximum speed is subject to specific rules. The maximum speed of a train on curved track for a given cant deficiency or unbalanced superelevation is determined by the following formula[1]:

where  is the height in inches that the outside rail is "superelevated" above the inside rail on a curve,

is the height in inches that the outside rail is "superelevated" above the inside rail on a curve,  is the unbalanced superelevation or cant deficiency in inches and

is the unbalanced superelevation or cant deficiency in inches and  is the degree of curvature in degrees per 100 feet (30 m).

is the degree of curvature in degrees per 100 feet (30 m).  is in miles per hour.

is in miles per hour.

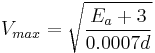

For the US standard maximum unbalanced superelevation of 3 inches, the formula is:

The maximum value of cant (the height of the outer rail above the inner rail) for a standard gauge railway is about 6 inches (150 mm). For high speed railways in Europe, maximum cant is 180mm (about 7 inches).[2]

Track unbalanced superelevation in the US is restricted to 3 inches (76 mm), though 4 inches (102 mm) is permissible by waiver. There is no general maximum set for European railways, some of which have curves with over 11 inches (280 mm) of unbalanced superelevation to permit high-speed transportation.[3] There are country-specific regulations that may apply, though.

Examples

In Australia, ARTC is increasing speed around curves sharper than 800 metres (2,625 ft) radius by replacing wooden sleepers with concrete ones so that the cant can be increased.

Rail cant

The rails themselves are now usually canted inwards by about 1 in 20 to 1 in 40.

In 1925, about 15 of 36 major railroads had adopted this practice. [4]

Roads

See also Geometric design of roads

In civil engineering, cant is often referred to as cross slope or camber. It helps rainwater drain from the road surface. Along straight or gently curved sections, the middle of the road is normally higher than the edges. This is called "normal crown" and helps shed rainwater off the sides of the road. During road works that involve lengths of temporary carriageway, the slope may be the opposite to normal – i.e. with the outer edge higher – which causes vehicles to lean towards oncoming traffic: in the UK this is indicated on warning signs as 'adverse camber'.

On more severe bends, the outside edge of the curve is raised, or superelevated, to help vehicles around the curve. The amount of superelevation increases with its design speed and with curve sharpness.

See also

References

- ^ Marquis, Brian. "Cant Deficiency, Curve Speeds and Tilt". http://www.highspeed-rail.org/Documents/305%20PRIIA%20Tilt%20presentation.pdf. Retrieved 2011-10-14.

- ^ 2002/732/EC. *, Commission Decision of 30 May 2002 concerning the Technical Specification for Interoperability

- ^ Zierke, Hans-Joachim. "Comparison of upgrades needs to recognize the difference in curve speeds". http://Zierke.com/shasta_route/pages/05curve-curve.html. Retrieved 2008-04-10.

- ^ ""KNOCK-KNEED" RAILS.". The Queenslander (Brisbane, Qld. : 1866 - 1939) (Brisbane, Qld.: National Library of Australia): p. 9. 7 February 1925. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article25099255. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

|

||||||||||||||