Brauer's theorem on forms

- There also is Brauer's theorem on induced characters.

In mathematics, Brauer's theorem, named for Richard Brauer, is a result on the representability of 0 by forms over certain fields in sufficiently many variables.[1]

Statement of Brauer's theorem

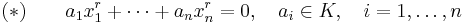

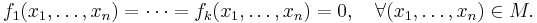

Let K be a field such that for every integer r > 0 there exists an integer ψ(r) such that for n ≥ ψ(r) every equation

has a non-trivial (i.e. not all xi are equal to 0) solution in K. Then, given homogeneous polynomials f1,...,fk of degrees r1,...,rk respectively with coefficients in K, for every set of positive integers r1,...,rk and every non-negative integer l, there exists a number ω(r1,...,rk,l) such that for n ≥ ω(r1,...,rk,l) there exists an l-dimensional affine subspace M of Kn (regarded as a vector space over K) satisfying

An application to the field of p-adic numbers

Letting K be the field of p-adic numbers in the theorem, the equation (*) is satisfied, since  , b a natural number, is finite. Choosing k = 1, one obtains the following corollary:

, b a natural number, is finite. Choosing k = 1, one obtains the following corollary:

- A homogeneous equation f(x1,...,xn) = 0 of degree r in the field of p-adic numbers has a non-trivial solution if n is sufficiently large.

One can show that if n is sufficiently large according to the above corollary, then n is greater than r2. Indeed, Emil Artin conjectured[2] that every homogeneous polynomial of degree r over Qp in more than r2 variables represents 0. This is obviously true for r = 1, and it is well-known that the conjecture is true for r = 2 (see, for example, J.-P. Serre, A Course in Arithmetic, Chapter IV, Theorem 6). See quasi-algebraic closure for further context.

In 1950 Demyanov[3] verified the conjecture for r = 3 and p ≠ 3, and in 1952 D. J. Lewis[4] independently proved the case r = 3 for all primes p. But in 1966 Guy Terjanian constructed a homogeneous polynomial of degree 4 over Q2 in 18 variables that has no non-trivial zero.[5] On the other hand, the Ax–Kochen theorem shows that for any fixed degree Artin's conjecture is true for all but finitely many Qp.

References

- ^ R. Brauer, A note on systems of homogeneous algebraic equations, Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society, 51, pages 749-755 (1945)

- ^ Collected papers of Emil Artin, page x, Addison–Wesley, Reading, Mass., 1965

- ^ Demyanov, V. B. (1950). "[On cubic forms over discrete normed fields]". Doklady Akademii Nauk SSSR 74: 889–891.

- ^ D. J. Lewis, Cubic homogeneous polynomials over p-adic number fields, Annals of Mathematics, 56, pages 473–478, (1952)

- ^ Guy Terjanian, Un contre-exemple à une conjecture d'Artin, C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris Sér. A–B, 262, A612, (1966)