Bertrand's theorem

In classical mechanics, Bertrand's theorem[1] states that only two types of central force potentials produce stable, closed orbits: (1) an inverse-square central force such as the gravitational or electrostatic potential

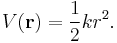

and (2) the radial harmonic oscillator potential

Contents |

General preliminaries

All attractive central forces can produce circular orbits, which are naturally closed orbits. The only requirement is that the central force exactly equals the centripetal force requirement, which determines the required angular velocity for a given circular radius. Non-central forces (i.e., those that depend on the angular variables as well as the radius) are ignored here, since they do not produce circular orbits in general.

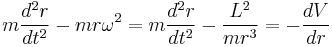

The equation of motion for the radius  of a particle of mass

of a particle of mass  moving in a central potential

moving in a central potential  is given by Lagrange's equations

is given by Lagrange's equations

where  and the angular momentum

and the angular momentum  is conserved. For illustration, the first term on the left-hand side is zero for circular orbits, and the applied inwards force

is conserved. For illustration, the first term on the left-hand side is zero for circular orbits, and the applied inwards force  equals the centripetal force requirement

equals the centripetal force requirement  , as expected.

, as expected.

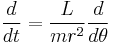

The definition of angular momentum allows a change of independent variable from  to

to

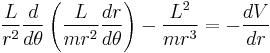

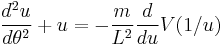

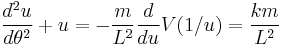

giving the new equation of motion that is independent of time

This equation becomes quasilinear on making the change of variables  and multiplying both sides by

and multiplying both sides by  (see also Binet equation)

(see also Binet equation)

Bertrand's theorem

As noted above, all central forces can produce circular orbits given an appropriate initial velocity. However, if some radial velocity is introduced, these orbits need not be stable (i.e., remain in orbit indefinitely) nor closed (repeatedly returning to exactly the same path). Here we show that stable, exactly closed orbits can be produced only with an inverse-square force or radial harmonic oscillator potential (a necessary condition). In the following sections, we show that those force laws do produce stable, exactly closed orbits (a sufficient condition).

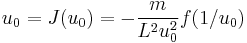

Define  as

as

where  represents the radial force. The criterion for perfectly circular motion at a radius

represents the radial force. The criterion for perfectly circular motion at a radius  is that the first term on the left-hand side be zero

is that the first term on the left-hand side be zero

-

(

where  .

.

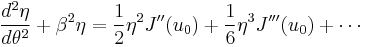

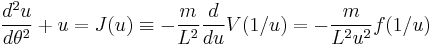

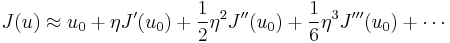

The next step is to consider the equation for  under small perturbations

under small perturbations  from perfectly circular orbits. On the right-hand side, the

from perfectly circular orbits. On the right-hand side, the  function can be expanded in a standard Taylor series

function can be expanded in a standard Taylor series

Substituting this expansion into the equation for  and subtracting the constant terms yields

and subtracting the constant terms yields

which can be written as

-

(

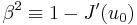

where  is a constant.

is a constant.  must be non-negative; otherwise, the radius of the orbit would vary exponentially away from its initial radius. (The solution

must be non-negative; otherwise, the radius of the orbit would vary exponentially away from its initial radius. (The solution  corresponds to a perfectly circular orbit.) If the right-hand side may be neglected (i.e., for small perturbations), the solutions are

corresponds to a perfectly circular orbit.) If the right-hand side may be neglected (i.e., for small perturbations), the solutions are

where the amplitude  is a constant of integration. For the orbits to be closed,

is a constant of integration. For the orbits to be closed,  must be a rational number. What's more, it must be the same rational number for all radii, since

must be a rational number. What's more, it must be the same rational number for all radii, since  cannot change continuously; the rational numbers are totally disconnected from one another. Using the definition of

cannot change continuously; the rational numbers are totally disconnected from one another. Using the definition of  along with equation (1),

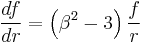

along with equation (1),

where  is evaluated at

is evaluated at  . Since this must hold for any value of

. Since this must hold for any value of  ,

,

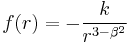

which implies that the force must follow a power law

Hence,  must have the general form

must have the general form

-

(

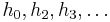

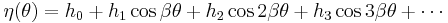

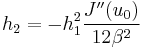

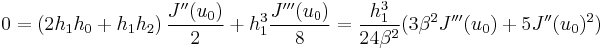

For more general deviations from circularity (i.e., when we cannot neglect the higher order terms in the Taylor expansion of  ),

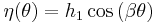

),  may be expanded in a Fourier series, e.g.,

may be expanded in a Fourier series, e.g.,

We substitute this into equation (2) and equate the coefficients belonging to the same frequency, keeping only the lowest order terms. As we show below,  and

and  are smaller than

are smaller than  , being of order

, being of order  .

.  , and all further coefficients, are at least of order

, and all further coefficients, are at least of order  . This makes sense since

. This makes sense since  must all vanish faster than

must all vanish faster than  as a circular orbit is approached.

as a circular orbit is approached.

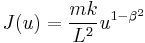

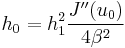

From the  term, we get

term, we get

where in the last step we substituted in the values of  and

and  .

.

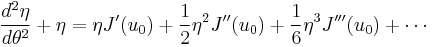

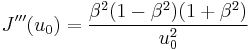

Using equations (3) and (1), we can calculate the second and third derivatives of  evaluated at

evaluated at  ,

,

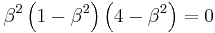

Substituting these values into the last equation yields the main result of Bertrand's theorem

Hence, the only potentials that can produce stable, closed, non-circular orbits are the inverse-square force law ( ) and the radial harmonic oscillator potential (

) and the radial harmonic oscillator potential ( ). The solution

). The solution  corresponds to perfectly circular orbits, as noted above.

corresponds to perfectly circular orbits, as noted above.

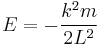

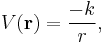

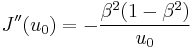

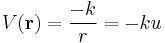

Inverse-square force (Kepler problem)

For an inverse-square force law such as the gravitational or electrostatic potential, the potential can be written

The orbit  can be derived from the general equation

can be derived from the general equation

whose solution is the constant  plus a simple sinusoid

plus a simple sinusoid

where  (the eccentricity) and

(the eccentricity) and  (the phase offset) are constants of integration.

(the phase offset) are constants of integration.

This is the general formula for a conic section that has one focus at the origin;  corresponds to a circle,

corresponds to a circle,  corresponds to an ellipse,

corresponds to an ellipse,  corresponds to a parabola, and

corresponds to a parabola, and  corresponds to a hyperbola. The eccentricity

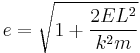

corresponds to a hyperbola. The eccentricity  is related to the total energy

is related to the total energy  (cf. the Laplace–Runge–Lenz vector)

(cf. the Laplace–Runge–Lenz vector)

Comparing these formulae shows that  corresponds to an ellipse,

corresponds to an ellipse,  corresponds to a parabola, and

corresponds to a parabola, and  corresponds to a hyperbola. In particular,

corresponds to a hyperbola. In particular,  for perfectly circular orbits.

for perfectly circular orbits.

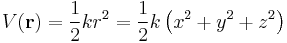

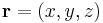

Radial harmonic oscillator

To solve for the orbit under a radial harmonic oscillator potential, it's easier to work in components  . The potential energy can be written

. The potential energy can be written

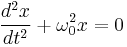

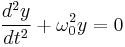

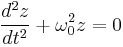

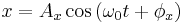

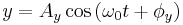

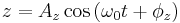

The equation of motion for a particle of mass  is given by three independent Lagrange's equations

is given by three independent Lagrange's equations

where the constant  must be positive (i.e.,

must be positive (i.e.,  ) to ensure bounded, closed orbits; otherwise, the particle will fly off to infinity. The solutions of these simple harmonic oscillator equations are all similar

) to ensure bounded, closed orbits; otherwise, the particle will fly off to infinity. The solutions of these simple harmonic oscillator equations are all similar

where the positive constants  ,

,  and

and  represent the amplitudes of the oscillations and the angles

represent the amplitudes of the oscillations and the angles  ,

,  and

and  represent their phases. The resulting orbit

represent their phases. The resulting orbit ![\mathbf{r}(t) = \left[ x(t), y(y), z(t) \right]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/f70d9e5f153bbbbb56755f3c79a07e88.png) is closed because it repeats exactly after a period

is closed because it repeats exactly after a period

The system is also stable because small perturbations in the amplitudes and phases cause correspondingly small changes in the overall orbit.

References

- ^ Bertrand J (1873). "Théorème relatif au mouvement d'un point attiré vers un centre fixe.". C. R. Acad. Sci. 77: 849–853.

Further reading

- Goldstein H. (1980) Classical Mechanics, 2nd. ed., Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-201-02918-9

- "An English translation of Bertrand's theorem". http://arxiv.org/PS_cache/arxiv/pdf/0704/0704.2396v1.pdf. Retrieved 2011-08-14.

- lt:Bertrano teorema Bertrano teorema (lietuviškai)

![J^{\prime}(u_0) = \frac{2}{u_0} \left[\frac{m}{L^2 u_0^2} f(1/u_0)\right] - \left[\frac{m}{L^2 u_0^2} f(1/u_0)\right]\frac{1}{f(1/u_0)} \frac{df}{du} = -2 %2B \frac{u_0}{f(1/u_0)} \frac{df}{du} = 1 - \beta^2](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/d153687394287defbcb1db233adc9e9d.png)

![h_{3} = -\frac{1}{8\beta^{2}}

\left[ h_{1}h_{2} \frac{J^{\prime\prime}(u_{0})}{2} %2B

h_{1}^{3} \frac{J^{\prime\prime\prime}(u_{0})}{24} \right]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/1ab2f2abdd66062089ebba387cebb2c7.png)

![u \equiv \frac{1}{r} = \frac{km}{L^{2}} \left[ 1 %2B e \cos \left( \theta - \theta_{0}\right) \right]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/fca22ac4be387e3325b4e015c460215c.png)