Artificial gravity

Artificial gravity is the varying (increase or decrease) of apparent gravity (g-force) via artificial means, particularly in space, but also on the Earth. It can be practically achieved by the use of some different forces, particularly the centrifugal force, "fictitious force", and (for short periods) linear acceleration.

The creation of artificial gravity is considered desirable for long-term space travel or habitation, for ease of mobility, for in-space fluid management, and to avoid the adverse long-term health effects of weightlessness.

Contents |

Requirement for gravity

Without g-force, space adaptation syndrome occurs in some humans and animals. Many adaptations occur over a few days, but over a long period of time bone density decreases, and some of this decrease may be permanent. The minimum g-force required to avoid bone loss is not known—nearly all current experience is with g-forces of 1 g (on the surface of the Earth) or 0 g in orbit. There has been insufficient time spent on the Moon to determine whether lunar gravity is sufficient.

A limited amount of experimentation has been done by Dr. Alfred Smith, of the University of California, with chickens, since they are bipeds, and mice experiencing high g-force over long periods in large centrifuges on the Earth.[1][2]

Rats have been exposed to continuous artificial gravity of 1 g during Russian biosatellite missions lasting two weeks. The muscle and bone loss in these animals was found to be less than rats in 0 g. Astronauts were exposed to artificial gravity levels ranging from 0.2 to 1 g for a few minutes during several spaceflight missions, using linear sleds or rotating chairs. They did not perceive any changes in their spatial orientation when the g level was lower than 0.5 g at the inner ear level, where the sensory receptors for gravity perception are located. [3]

Methods for generating artificial gravity

Gravity can be simulated in numerous ways:

Rotation

A rotating spacecraft will produce the feeling of gravity on its inside hull. The rotation drives any object inside the spacecraft toward the hull, thereby giving the appearance of a gravitational pull directed outward. Often referred to as a centrifugal force, the "pull" is actually a manifestation of the objects inside the spacecraft attempting to travel in a straight line due to inertia. The spacecraft's hull provides the centripetal force required for the objects to travel in a circle (if they continued in a straight line, they would leave the spacecraft's confines). Thus, the gravity felt by the objects is simply the reaction force of the object on the hull reacting to the centripetal force of the hull on the object, in accordance with Newton's Third Law.

From the point of view of people rotating with the habitat, artificial gravity by rotation behaves in some ways similarly to normal gravity but has the following effects:

- Centrifugal force: Unlike real gravity which pulls towards a center, this pseudo-force that appears in rotating reference frames gives a rotational 'gravity' that pushes away from the axis of rotation. Artificial gravity levels vary proportionately with the distance from the centre of rotation. With a small radius of rotation, the amount of gravity felt at one's head would be significantly different from the amount felt at one's feet. This could make movement and changing body position awkward. In accordance with the physics involved, slower rotations or larger rotational radii would reduce or eliminate this problem.

- The Coriolis effect gives an apparent force that acts on objects that move. This force tends to curve the motion in the opposite sense to the habitat's spin. Effects produced by the Coriolis effect act on the inner ear and can cause dizziness, nausea and disorientation. Experiments have shown that slower rates of rotation reduce the Coriolis forces and its effects. It is generally believed that at 2 rpm or less no adverse effects from the Coriolis forces will occur, at higher rates some people can become accustomed to it and some do not, but at rates above 7 rpm few if any can become accustomed.[4] It is not yet known if very long exposures to high levels of Coriolis forces can increase the likelihood of becoming accustomed. The nausea-inducing effects of Coriolis forces can also be mitigated by restraining movement of the head.

This form of artificial gravity gives additional system issues:

- Kinetic energy: Spinning up parts or all of the habitat requires energy. This would require a propulsion system and propellant of some kind to spin up (or spin down) or a motor and counterweight of some kind (possibly in the form of another living area) to spin in the opposite direction.

- Extra strength is needed in the structure to keep it from flying apart due to the rotation. However, the amount of structure needed over and above that to hold a breathable atmosphere (10 tonnes force per square metre at 1 atmosphere) is relatively modest for most structures.

- If parts of the structure are intentionally not spinning, friction and similar torques will cause the rates of spin to converge (as well as causing the otherwise-stationary parts to spin), requiring motors and power to be used to compensate for the losses due to friction.

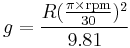

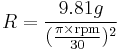

| Calculations |

|---|

g = Decimal fraction of Earth gravity |

The engineering challenges of creating a rotating spacecraft are comparatively modest to any other proposed approach. Theoretical spacecraft designs using artificial gravity have a great number of variants with intrinsic problems and advantages. To reduce Coriolis forces to livable levels, a rate of spin of 2 rpm or less would be needed. To produce 1g, the radius of rotation would have to be 224 m (735 ft) or greater, which would make for a very large spaceship. To reduce mass, the support along the diameter could consist of nothing but a cable connecting two sections of the spaceship, possibly a habitat module and a counterweight consisting of every other part of the spacecraft. It is not yet known if exposure to high gravity for short periods of time is as beneficial to health as continuous exposure to normal gravity. It is also not known how effective low levels of gravity would be to countering the adverse effects on health of weightlessness. Artificial gravity at 0.1g would require a radius of only 22 m (74 ft). Likewise, at a radius of 10 m, about 10 rpm would be required to produce Earth gravity (at the hips; gravity would be 11% higher at the feet), or 14 rpm to produce 2g. If brief exposure to high gravity can negate the health effects of weightlessness, then a small centrifuge could be used as an exercise area.

The Gemini 11 mission attempted to produce artificial gravity by rotating the capsule around the Agena Target Vehicle which it was attached to by a 36-meter tether. They were able to generate a small amount of artificial gravity, about 0.00015 g, by firing their side thrusters to slowly rotate the combined craft like a slow-motion pair of bolas.[5] The resultant force was too small to be felt by either astronaut, but objects were observed moving towards the "floor" of the capsule.[6]

The Mars Gravity Biosatellite was a proposed mission meant to study the effect of artificial gravity on mammals. An artificial gravity field of 0.38g (Mars gravity) was to be produced by rotation (32 rpm, radius of ca. 30 cm). Fifteen mice would have orbited Earth (Low Earth orbit) for five weeks and then land alive. However the program was canceled on June 24, 2009 due to lack of funding and shifting priorities at NASA.[7]

Linear acceleration

Linear acceleration, even at a low level, can provide sufficient g-force to provide useful benefits. Any spacecraft could, in theory, continuously accelerate in a straight line, forcing objects inside the spacecraft in the opposite direction of the direction of acceleration.

Most chemical reaction rockets already accelerate at a sufficient rate to produce several times Earth's g-force but can only maintain these accelerations for several minutes because of a limited supply of fuel.

A propulsion system with a very high specific impulse (that is, good efficiency in the use of reaction mass that must be carried along and used for propulsion on the journey) could accelerate more slowly producing useful levels of artificial gravity for long periods of time. A variety of electric propulsion systems provide examples. Two examples of this long-duration, low-thrust, high-impulse propulsion that have either been practically used on spacecraft or are planned in for near-term in-space use are Hall effect thrusters and Variable specific impulse magnetoplasma rockets (VASIMR). Both provide very high specific impulse but relatively low thrust, compared to the more typical chemical reaction rockets. They are thus ideally suited for long-duration firings which would provide limited amounts of, but long-term, milli-g levels of artificial gravity in spacecraft..

Low-impulse but long-term linear acceleration has been proposed for various interplanetary missions. For example, even heavy (100 tonne) cargo payloads to Mars could be transported to Mars in 27 months and retain approximately 55 percent of the LEO vehicle mass upon arrival into a Mars orbit, providing a low-gravity gradient to the spacecraft during the entire journey.[8]

Constant linear acceleration could theoretically provide relatively short flight times around the solar system. If a propulsion technique able to support 1g of acceleration continuously were available, a spaceship accelerating (and then decelerating for the second half of the journey) at 1g would reach Mars within a few days.[9]

In a number of science fiction plots, acceleration is used to produce artificial gravity for interstellar spacecraft, propelled by as yet theoretical or hypothetical means.

This effect of linear acceleration is very well understood, and is routinely used for 0g cryogenic fluid management for post-launch (subsequent) in-space firings of upper stage rockets.[10]

Mass

Another way artificial gravity may be achieved is by installing an ultra-high density mass in a spacecraft so that it would generate its own gravitational field and pull everything inside towards it. Technically this is not artificial gravity—it is natural gravity, gravity in its original sense. An extremely large amount of mass would be needed to produce even a tiny amount of noticeable gravity. A large asteroid could exert several thousandths of a g and, by attaching a propulsion system of some kind, would qualify as a space ship, though gravity at such a low level might not have any practical value. In addition, the mass would obviously need to move with the spacecraft; if the spacecraft is to be accelerated significantly, this would greatly increase fuel consumption. Because gravitational force is inversely proportional to the square of the distance from the center of mass, it would be possible to have significant levels of gravity with much less mass than such an asteroid if this mass could be made much denser than current materials (see neutronium). In principle, small charged black holes could be used and held in position with electromagnetic forces. However, carrying a sufficient quantity of mass to form significant gravity fields in a spacecraft is well beyond current technology.

Tidal forces

In a planetary orbit, artificial gravity can be obtained from the tidal force by two spacecraft above each other (or one spacecraft and another mass) connected by a tether. See also tidal stabilization.

Magnetism

A similar effect to gravity has been created through diamagnetism. It requires magnets with extremely powerful magnetic fields. Such devices have been made that were able to levitate at most a small mouse[11] and thus produced a 1 g field to cancel the Earth's; yet it required a magnet and system that weighed thousands of kilograms, was kept superconductive with expensive cryogenics, and required 6 megawatts of power.[12]

With such extremely strong magnetic fields, safety for use with humans is unclear. In addition, it would involve avoiding any ferromagnetic or paramagnetic materials near the strong magnetic field required for diamagnetism to be evident.

Facilities using diamagnetism may prove workable for laboratories simulating low gravity conditions here on Earth. The mouse was levitated against Earth's gravity, creating a condition similar to microgravity. Lower forces may also be generated to simulate a condition similar to lunar or Martian gravity with small model organisms.

Gravity generator/gravitomagnetism

In science fiction, artificial gravity (or cancellation of gravity) or "paragravity"[13][14] is sometimes present in spacecraft that are neither rotating nor accelerating. At present, there is no confirmed technique that can simulate gravity other than actual mass or acceleration. There have been many claims over the years of such a device. Eugene Podkletnov, a Russian engineer, has claimed since the early 1990s to have made such a device consisting of a spinning superconductor producing a powerful gravitomagnetic field, but there has been no verification or even negative results from third parties. In 2006, a research group funded by ESA claimed to have created a similar device that demonstrated positive results for the production of gravitomagnetism, although it produced only 100 millionths of a g.[15] String theory predicts that gravity and electromagnetism unify in hidden dimensions and that extremely short photons can enter those dimensions.[16]

Buoyancy

An approximation to zero gravity can be produced with buoyancy. The approximation is imperfect. The higher density fluid needed for buoyancy (such a water) produces greater drag on the body. A human being's sense of which direction is "up" is also not fooled. The technique is nevertheless useful and practical in many situations. For example, NASA uses a large pool to train astronauts for extra vehicular activity.

Training for high or low gravitational environments

Centrifuge

High-G training is done by aviators and astronauts who are subject to high levels of acceleration ('G') in large-radius centrifuges. It is designed to prevent a g-induced Loss Of Consciousness (abbreviated G-LOC), a situation when g-forces move the blood away from the brain to the extent that consciousness is lost. Incidents of acceleration-induced loss of consciousness have caused fatal accidents in aircraft capable of sustaining high-g for considerable periods.

Parabolic flight

Weightless Wonder is the nickname for the NASA aircraft that flies parabolic trajectories and briefly provides a nearly weightless environment in which to train astronauts, conduct research, and film motion pictures.[17] The parabolic trajectory creates a vertical linear acceleration which matches that of gravity, giving zero-g for a short time, usually 20–30 seconds, followed by approximately 1.8g for a similar period. The nickname Vomit Comet is also used to refer to motion sickness that is often experienced by the aircraft passengers during these parabolic trajectories. Such reduced gravity aircraft are nowadays operated by several organizations world wide.

Neutral buoyancy

A Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory (NBL) is an astronaut training facility, such as the Sonny Carter Training Facility at the NASA Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas.[18] The NBL is a large indoor pool of water, the largest in the world,[19] in which astronauts may perform simulated EVA tasks in preparation for space missions. The NBL contains full-sized mock-ups of the Space Shuttle cargo bay, flight payloads, and the International Space Station (ISS).[20]

The principle of neutral buoyancy is used to simulate the weightless environment of space.[18] The suited astronauts are lowered into the pool using an overhead crane and their weight is adjusted by support divers so that they experience no buoyant force and no rotational moment about their center of mass.[18] The suits worn in the NBL are down-rated from fully flight-rated EMU suits like those in use on the space shuttle and International Space Station.

The NBL tank itself is 202 feet (62 m) in length, 102 feet (31 m) wide, and 40 feet 6 inches (12.34 m) deep, and contains 6.2 million gallons (23.5 million litres) of water.[20][21] Divers breathe nitrox while working in the tank.[22][23]

Neutral buoyancy in a pool is not weightlessness, since the balance organs in the inner ear still sense the up-down direction of gravity. Also, there is a significant amount of drag presented by water.[24] Generally, drag effects are minimized by doing tasks slowly in the water. Another difference between neutral buoyancy simulation in a pool and actual EVA during spaceflight is that the temperature of the pool and the lighting conditions are maintained constant.

Proposals

There have been a number of proposals that have incorporated artificial gravity into their design.

- Discovery II: Was a 2005 vehicle proposal capable of delivering 172 mt to Jupiter's orbit in only 118 days. A very small portion of the 1,690 mt craft would incorporate a centrifuge where the crew would reside.[25]

- Multi-Mission Space Exploration Vehicle (MMSEV): this 2011 NASA proposal for a long-duration crewed space transport vehicle includes a rotational artificial gravity space habitat intended to promote crew-health for a crew of up to six persons on missions of up to two years duration. The partial-g torus-ring centrifuge would utilize both standard metal-frame and inflatable spacecraft structures and would provide 0.11 to 0.69g if built with the 40 feet (12 m) diameter option.[26][27]

- ISS Centrifuge Demo: Also proposed in 2011 as a demonstration project preparatory to the final design of the larger torus centrifuge space habitat for the Multi-Mission Space Exploration Vehicle. The structure would have an outside diameter of 30 feet (9.1 m) with a 30 inches (760 mm) ring interior cross-section diameter and would provide 0.08 to 0.51g partial gravity. This test and evaluation centrifuge would have the capability to become a Sleep Module for ISS crew.[26]

- Mars Direct: A plan for a manned mars mission created by NASA engineers Robert Zubrin and David Baker in 1990, later expanded upon in Zubrin's 1996 book The Case for Mars. The "Mars Habitat Unit", which would carry astronauts to Mars to join the previously-launched "Earth Return Vehicle", would have had artificial gravity generated during flight by tying the spent upper stage of the booster to the Habitat Unit, and setting them both rotating about a common axis.

See also

- Centrifugal force

- Gravitational induction

- Coriolis force

- Fictitious force

- Accelerated reference frame

- Artificial gravity in fiction

- Space habitat

- Centrifuge Accommodations Module

- Anti-gravity

- Rotating wheel space station

References

- ^ Great Mambo Chicken And The Transhuman Condition: Science Slightly Over The Edge

- ^ "Science: High-G Life". Time. 1960-05-09. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,897495,00.html.

- ^ Clément G, Bukley A (2007) Artificial Gravity. Springer: New York

- ^ Hecht, H., Brown, E. L., & Young, L. R., et al. (2–7 June 2002). "Adapting to artificial gravity (AG) at high rotational speeds". Proceedings of "Life in space for life on Earth". 8th European Symposium on Life Sciences Research in Space. 23rd Annual International Gravitational Physiology Meeting. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/full/2002ESASP.501..151H. Retrieved 2011-02-07.

- ^ Gatland, Kenneth (1976). Manned Spacecraft, Second Revision. New York, NY, USA: MacMillan Publishing Co., Inc. pp. 180–182. ISBN 0025428209.

- ^ Clément G, Bukley A (2007) Artificial Gravity. Springer: New York

- ^ http://www.marstoday.com/news/viewsr.rss.html?pid=31612

- ^ VASIMR VX-200 Performance and Near-term SEP Capability for Unmanned Mars Flight, Tim Glover, Future in Space Operations (FISO) Colloquium, pages 22 and 25, 2011-01-19, accessed 2011-02-01.

- ^ Clément, Gilles; Bukley, Angelia P. (2007). Artificial Gravity. Springer New York. p. 35. ISBN 0-387-70712-3. http://books.google.com/books?id=YUcjOsG0hi0C., Extract of page 35

- ^ Jon Goff, et al. (2009). "Realistic Near-Term Propellant Depots". American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. http://selenianboondocks.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/09/NearTermPropellantDepots.pdf. Retrieved 2011-02-07 quote=developing techniques for manipulating fluids in microgravity, which typically fall into the category known as settled propellant handling. Research for cryogenic upper stages dating back to the Saturn S-IVB and Centaur found that providing a slight acceleration (as little as 10-4 to 10-5 g of acceleration) to the tank can make the propellants assume a desired configuration, which allows many of the main cryogenic fluid handling tasks to be performed in a similar fashion to terrestrial operations. The simplest and most mature settling technique is to apply thrust to the spacecraft, forcing the liquid to settle against one end of the tank..

- ^ "U.S. scientists levitate mice to study low gravity". Reuters. 2009-09-11. http://www.reuters.com/article/scienceNews/idUSTRE58A02G20090911.

- ^ 20 tesla Bitter solenoid

- ^ Collision Orbit, 1942 by Jack Williamson

- ^ Pale Blue Dot: A Vision of the Human Future in Space by Carl Sagan, Chapter 19

- ^ http://www.esa.int/SPECIALS/GSP/SEM0L6OVGJE_0.html

- ^ The Elegant Universe: Superstrings, Hidden Dimensions and the Quest for The Ultimate Theory, by Brian Greene

- ^ NASA "Weightless Wonder"

- ^ a b c Strauss S (July 2008). "Space medicine at the NASA-JSC, neutral buoyancy laboratory". Aviat Space Environ Med 79 (7): 732–3. PMID 18619137.

- ^ "Behind the scenes training". NASA. May 30, 2003. http://spaceflight.nasa.gov/shuttle/support/training/nbl/facilities.html. Retrieved March 22, 2011.

- ^ a b Strauss S, Krog RL, Feiveson AH (May 2005). "Extravehicular mobility unit training and astronaut injuries". Aviat Space Environ Med 76 (5): 469–74. PMID 15892545. http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/asma/asem/2005/00000076/00000005/art00008. Retrieved 2008-08-27.

- ^ "NBL Characteristics". About the NBL. NASA. June 23, 2005. http://dx12.jsc.nasa.gov/about/index.shtml.

- ^ Fitzpatrick DT, Conkin J (2003). "Improved pulmonary function in working divers breathing nitrox at shallow depths". Undersea Hyperb Med abstract 30 (Supplement). http://archive.rubicon-foundation.org/1273. Retrieved 2008-08-27.

- ^ Fitzpatrick DT, Conkin J (July 2003). "Improved pulmonary function in working divers breathing nitrox at shallow depths". Aviat Space Environ Med 74 (7): 763–7. PMID 12862332. http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/asma/asem/2003/00000074/00000007/art00011. Retrieved 2008-08-27.

- ^ Pendergast D, Mollendorf J, Zamparo P, Termin A, Bushnell D, Paschke D (2005). "The influence of drag on human locomotion in water". Undersea Hyperb Med 32 (1): 45–57. PMID 15796314. http://archive.rubicon-foundation.org/4037. Retrieved 2008-08-27.

- ^ "Realizing "2001: A Space Odyssey": Piloted Spherical Torus Nuclear Fusion Propulsion" (in English). Cleveland, Ohio: NASA. 2005-03. http://gltrs.grc.nasa.gov/reports/2005/TM-2005-213559.pdf. Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- ^ a b NAUTILUS - X: Multi-Mission Space Exploration Vehicle, Mark L. Holderman, Future in Space Operations (FISO) Colloquium, 2011-01-26, accessed 2011-01-31.

- ^ NASA NAUTILUS-X: multi-mission exploration vehicle includes centrifuge, which would be tested at ISS, RLV and Space Transport News, 2011-01-28, accessed 2011-01-31.

External links

- List of peer review papers on artificial gravity

- Mars gravity experiment homepage

- Revolving artificial gravity calculator

- Overview of artificial gravity in Sci-Fi and Space Science

- NASA's Java simulation of artificial gravity

- Variable Gravity Research Facility (xGRF), concept with tethered rotating satellites, perhaps a Bigelow expandable module and a spent upper stage as a counterweight.